NFT? WTF!

NFTs have currently taken the world by storm, mainly thanks to one Mike Winkelmann, a digital artist from Wisconsin who goes by the name Beeple. When not being a dad and driving a Toyota Corolla, he deals with pixels and not paints. And last month, a piece of digital art he created called ‘Everydays: The First 5000 Days’ sold at auction for USD69 million.

Just so we’re all on the same page, digital art doesn’t physically exist. You can’t look at it in an art gallery (unless you’re looking at a computer screen), touch it or stick it in a frame. Up until a few years ago, the very fact that a painting or an image didn’t exist IRL made it almost worthless. Because why would anyone pay for something that could be copied and pasted from the internet?

Traditional art (as the form will now forever be known) gets its value from being unique, and quite rare. My grandfather would paint a landscape once, and only once. If anyone quite fancied the look of it in their living room, they had to pay decent money for it-because it was, after all, one of a kind.

But technology has a way of disrupting things, which is where cryptocurrency (aka the problem child of the financial world) comes in.

Crypto works because of blockchain technology. Blockchain is most easily described as some form of IT wizardry that constantly tracks where your money has been, where it is now and where it’s gone.

Or in complicated financial terms, it’s a ‘decentralised, distributed ledger that records the provenance of a digital asset or token’. Some crypto clever-clogs figured out a way to use the blockchain not just to track digital currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, but anything that exists digitally. All of a sudden, you could make something online and register it as being unique, rare or original. And the NFT was born.

“A lot of people find this whole thing, this whole world of crypto quite confusing,” Jamil Abu-Wardeh, a crypto sceptic- turned-enthusiast (who on the day we talked was wearing a T-shirt with the word Bitcoin emblazoned on the front), says. “The way most people see it, it’s an investment in thin air.”

“But look at the stock market, which is a valuation of companies based on future capabilities. Tesla is valued at however many billions because many people agree that it will make a very large number of cars. It hasn’t done that yet, but that’s what drives its value,” says Abu-Wardeh. “What I am getting at is that these types of markets do exist today; people just haven’t made the same mental connection with them yet.”

Truth be told, the art world is uniquely suited to benefit from an ethereal currency like crypto. Art is subjective, and the industry has been taking rich sums of money from collectors and benefactors since the 16th-century Renaissance. Case in point, Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ sold for an eye-watering USD450 million at Christie’s New York in 2016 after a long-drawn outbidding war. The ultimate winner of the masterpiece turned out to be Mohammed bin Salman, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia.

Fair enough, da Vinci is a pretty big deal (he’s known as the OG in art circles). But what about contemporary art? As anyone who has walked into the Tate Modern and thought, yeah, I could do that will attest, throwing some paint at a wall doesn’t seem quite as much effort as Rembrandt must have put into his masterpieces.

And yet, last October a picture of a rectangle and a square (albeit painted by Mark Rothko) sold for USD31 million, and a few years before that Andy Warhol’s painting of a tin of Campbell’s soup went for a cool USD11.8 million. One of last year’s biggest sales came from Sotheby’s in June; Francis Bacon’s ‘Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus’ took more than USD84 million at the auction block. It was definitely a piece that Bryan Shambler would have described as a load of rubbish.

But despite the fact that most people can’t tell the difference between a blockchain and a bitcoin; cryptocurrency is not exactly new. The first white paper about the financial technology was published in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto-the actual identity of this person (or persons) is a mystery-and quickly led to the creation of a huge number of cryptocurrencies such as Ethereum, Tether, Litecoin and Dogecoin (which uses a Japanese Shiba Inu dog as its mascot). So why are we only hearing about NFTs now?

“NFTs and how they have disrupted the art market is obviously the ‘conversation du jour’,” Benedetta Ghione, executive director of Art Dubai, says. “But they have been gathering momentum over the past few years. What we are seeing here is figureheads becoming more visible, and a sense of hierarchy is just getting started. Now there is a developing A-list of artists working in the medium of digital art, and attention is particularly gathering around them.”

The sale of Beeple’s work for USD69 million was surely a watershed moment for NFT art, and one which attracted attention outside of the relative crypto and art worlds.

“If nothing else, these key moments are interesting as they track the history and trajectory of the commercial side of the art world,” Ghione says. “I am not sure if these types of results are here to stay, but they are certainly an indication of a profoundly shifting landscape.”

No one can pinpoint exactly when NFTs were invented, because the world of cryptocurrency is a murky one. Some attribute the first NFTs as being digital versions of physical trading cards such as Pokemon and Magic: The Gathering (which are also seeing a huge resurgence on the collector’s market). Others say that it was when Bitcoin enthusiasts on forums like Reddit started to create and share ‘rare memes’. What we do know is when NFT got its first big success story.

NO ONE CAN PINPOINT EXACTLY WHEN NFTS WERE INVENTED, BECAUSE THE WORLD OF CRYPTOCURRENCY IS A MURKY ONE.

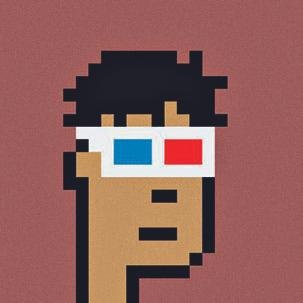

In 2017, self-styled creative technologists John Watkinson and Matt Hall decided to start their own blockchain-backed art project called CryptoPunks (the name itself is a nod to the term cytherpunks, a group who began experimenting with the precursor to blockchain back in the 1990s). CryptoPunks are a set of unique characters that look like they were rendered inside an old 8-bit video game. Characters are limited to 10,000 and no two characters are the same.

Interestingly, this being an art project, Watkinson and Hall decided to give their original CryptoPunk characters away for free and all of them were quickly snapped up. This has since led to a thriving secondhand market, and as of today CryptoPunk NFTs have traded upwards of 110,000 Ethereum coins (which currently convert to USD175 million in real money).

Whereas my grandfather mainly sold his paintings through word of mouth (or to someone who had wandered over to see what he was sat painting), a vast majority of NFTs—including said CryptoPunk characters—change hands on a few online marketplaces like OpenSea, Rarible and Atomic Assets.

Think of them like the eBay of the digital art space. However, instead of looking at secondhand watches and old sports memorabilia, these platforms are home to NFTs of all shape, size, medium and file type.

A casual glance at the homepage of OpenSea (which is regarded as digital art’s largest marketplace), for example, shows me a picture of a digital monkey wearing a pirate hat (which goes by Ape In Finance), a variety of 8-bit animated animals bopping up and down (called Chubbies), and a short film titled A Trip to the Red Planet that’s a digital homage to the early film innovator Georges Méliès’s seminal A Trip to the Moon.

“This is what makes NFTs so exciting,” Simon Hudson, the founder of Cheeze, Inc, says. His app lets photographers register (called minting in crypto speak) their photos and videos on the blockchain. “For the first time, there is serious interest not just in art forms like paintings and sculpture, and things you would put in a frame. Now people can start collecting virtual reality art that you’d need to wear a headset to see. Or pieces of internet history, like Jack Dorsey’s tweet.”

Indeed, art isn’t the sole reason why NFTs have become such a hot commodity. You can ‘mint’ just about anything that exists in digital form. Case in point, basketball’s NBA Top Shot—which captures distinctive highlights from a particular match and turns them into video trading cards. So far, it has amassed more than 250,000 users and USD400 million in sales.

Elsewhere, NFTs have led to a booming property market —digital property, that is—based in virtual worlds. Just last month, a Canadian buyer spent half a million dollars on a digital home, in what was the first sale of its kind (the house, designed by digital architect Krista Kim, exists only on a virtual rendering of Mars).

“Earlier this year we purchased a plot of land in a digital metaverse,” Hudson says. “We’ve already commissioned anarchitect—which, I admit, does sound a bit funny—to discuss the layout of our first gallery that will exist inside this virtual world. It will work the same way a traditional one does; hold launch events, entertain perspective buyers, and welcome visitors to check out new and interesting photographers.”

One thing that has certainly helped capture the world’s attention with regards to NFTs—well, beyond owning a house on pretend Mars—is how accessible they appear to be. “Instagram has proven that there are a lot of very talented digital artists out there,” Hudson admits. “NFTs might allow them to start making money.”

Indeed, there has never been more interest in buying or selling NFTs. And while there is no exact figure to pinpoint exactly how popular it has become (cryptocurrency is by design decentralised), the currency that powers the ‘minting’ process has grown 255 percent this year.

This has led to people inside the crypto and art worlds to label the events of recent months as a gold rush. However, if there’s gold in them there hills, then I am just the type of person to grab my pan and head to the nearest digital stream (after all, art does flow through my veins).

Thinking back, my grandfather spent most of his life honing his skills. He sketched as a boy, eventually graduating to oil on canvas and then watercolour. And even much later in his life, he would continue to improve his craft through studying books.

ONE THING THAT HAS HELPED CAPTURE THE WORLD’S ATTENTION WITH REGARDS TO NFTS IS HOW ACCESSIBLE THEY APPEAR TO BE.

It turns out being a digital artist is far, far easier. You’ll first need a digital wallet. Much like a physical billfold, your digital wallet is where all your cryptocurrency and NFTs are stored. After that, you need to sign up to an NFT marketplace (in the same way you would create an Amazon account) and link them both up. Then comes the real challenge; the doing of the art.

Unlike my grandfather, I wouldn’t say I have any real artistic talent. But after a quick glance over some of the more popular NFT marketplaces, it would appear that hasn’t stopped most people.

Emboldened by the mediocrity, I quickly put together a collection of moving gifs—most of them involving a spinning money symbol-and a flowery summary of the collection: “My art, you see, is a personal investigation into the many ways currency hath crept beyond the physical, into the digital realm.”

Once the hard part was over, I authenticated my art as an NFT by paying a ‘gas fee’—which is the name given to the cost of registering your token on the blockchain—set a price, and waited for the crypto bucks to roll in.

Except, it didn’t. Two weeks after registering my digital art, and I haven’t had a sniff of interest. Not one lowly bid.

There is little doubt that NFTs will change the art world for the better. The success of Beeple—who previously would have found it impossible to make a living as a digital artist—is proof of that.

However, crypto gold rush or not, the value of art remains in the eye of the beholder. It remains subjective. People will always pay money for a piece or a collection that speaks to them, no matter the format or the medium (be that physical or digital).

In that vein, traditional art and NFTs are much the same. There will always be people who are willing to pay lots of money for something that impacts their life. And similarly, there will be people that scoff at the very notion of paying lots of money for art; be it two squares on canvas, or an 8-bit cartoon character.

What they won’t pay for, it seems, is people—like myself —trying to jump on the crypto bandwagon and make a quick buck. Especially if the art they produced is a load of rubbish.