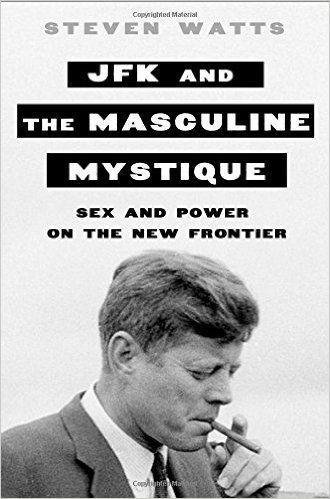

Newslink: The real President JFK: Even a political titan faces self-doubt

During the 1960 election campaign, he seemed tough, glamorous, as daring as the James Bond character he loved. Part of that appeal came from a widely shared war story. Kennedy spoke of his naval career on the campaign trail, recalling the Japanese destroyer that rammed his ship during World War II and sliced it in half. The young lieutenant had suffered a back injury, but he managed to swim to a nearby island, towing another crew member to safety by his life vest strap.

With a deeply researched cultural analysis, Watts argues that Kennedy’s popularity largely depended on his, well, manliness. “The Democrat,” he wrote, “embodied the individualist spirit of the maverick male eager to throw off the heavy hand of tradition.”

It was a persuasive message for the time. After the war, the United States prospered. So much, in fact, that social critics worried that the American male was growing flabby. With no battle to fight, he sat in an office and embraced a cushy lifestyle. Women, meanwhile, surged into the workplace, taking up jobs once reserved for men. The cultural shift triggered some unease. Watts cites a 1958 Esquire essay that captured this mood. Women seemed “an expanding, aggressive force, seizing new domains like a conquering army,” the Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote, while men took a defensive posture, “hardly able to hold their own and gratefully [accepting] assignments from their new rulers.” Schlesinger, later a JFK adviser, called it “a crisis of American masculinity.”