Pakistan: The Perfect Dragon-Trap

Lord T'an's Strategy #11: "Sacrifice the Peach to Secure the Plum"

"Force absolutely incurs damage.

By decreasing yin, one increases yang."

Lord T'an's Strategy #12: "Lead Away the Sheep When Conditions are Right"

"Always take advantage of a minute opening;

always take a minute gain.

Small yin becomes small yang."

One of the first big stories of 2018 (which has largely been forgotten by by easily-distracted Western netizens who deemed the Academy Awards, Mr. and Mrs. Obama's rather ridiculous portraits, Donald Trump's insufferable tweets, a moronic and juvenile wave of insulting protests by members of the NFL and an Olympian's petty war of words with VP Mike Pence more worthy of their short attention spans than anything of actual geopolitical relevance) was the breakdown of the US-Pakistan alliance. Immediately, news sources on both sides of the Pacific began running with the CCP's favorite slogan: "America in Retreat." To the American media, the loss of what we're told to believe was a "vital ally" in the Afghan conflict was held up as a historic blunder. The Chinese, for their part, have gotten extensive mileage out of holding it up as a sign of a diminishing America which, according to Xi-ist doctrine, will give way to a "Rising China." As for me, well, I'll put it simply:

I cannot think of any place in this world for China (and their PLA) to be that works out more in America's favor than to see them than hip-deep in Central Asia.

In this article, I intend to answer five basic questions. Why was America allied with Pakistan in the first place, why is the alliance ending, why is China moving in, what does America lose from this (hint: not much), and what does America gain?

Why Did We Break Up? Well, Why Were We Together In the First Place?

The history of the alliance structures of the "Big Three (the U.S, China and Russia, as both the USSR and the Russian Federation)" in Central Asia is a Gordian Knot of "the enemy of my enemy is my friend even though he is friends with the other enemy of my enemy who is still my enemy," but to give a grossly simplified explanation, it goes back to the dawn of the Cold War. India and Pakistan hated each other (Friedman, The Next Decade 107). The U.S. and the USSR were starting to growl at each other. India and the USSR became allies, so it was only logical that the U.S. and Pakistan would become allies. China, which was not on super-friendly terms with the U.S. but was terrified of the USSR, and had been butting heads with India for supremacy in Central Asia since Rome was a village, realized that she and Pakistan shared two enemies (India and the USSR) and a pseudo-ally (the U.S.). So, China joined hands with Pakistan along the way as well (Friedman, GPF). If you can conjure an image of two jocks pretending to be on friendly terms with one another while competing for the affections of a cheerleader and occasionally agreeing to protect the cheerleader from the local jerk, then you have a decent (if amateurish) analogy the last few decades of US-Sino-Pakistani maneuvering, at least until the jerk had an accident and was put in a wheelchair (the fall of the USSR).

Meanwhile, other factors were at play. U.S. foreign policy is a thing not many truly understand. To admirers, she's "the Arsenal of Democracy," while her critics call her the "New Imperialists." Neither of these is true. The fact is since that for most of US history (at least since the end of the Mexican-American War made U.S. the dominant force in the "new World") the US has maintained a policy of making sure no country is able to achieve unchallenged dominance in their region, and especially that no country should dominate Eurasia, because any power capable of doing that would be a clear and present threat not to our hegemony (which didn't exist at the time we established this policy and has never been really essential) but to our very existence.

Part of that strategy (as Friedman outlines in extensive detail throughout The Next Decade) has been to maintain regional balances of power, and the most efficient way of doing this without garrisoning troops abroad for long periods of time has been to pick the two strongest countries in any given region, prop them up in opposition to one another and walk away, only interfering if one starts to get the upper hand on the other. Iraq/Iran (which George W. bush made a huge mess of by shattering Iraq, meaning it's going to be rough over there until around 2025 when balance is restored as Iran/Turkey), China/Japan (one that is being addressed right now), Israel/Egypt, Germany/Britain, Russia/Intermarium, Brazil/Argentina and of course, India/Pakistan. Even though Indo-American relations have warmed quite a bit since the fall of the USSR, the U.S. still has not wanted to see India achieve utter dominance of her region, so we've maintained at least cordial relations with Pakistan. As George Friedman writes of this balance in The Next Decade (107), "While India is the stronger, Pakistan has the more defensible terrain, although its heartland is more exposed to India."

The final piece of this puzzle has been the war in Afghanistan. Pakistan has been giving the U.S. lukewarm support in the war, but the U.S. has wanted more. The U.S. has given aid to Pakistan in the form of money and military hardware, but Pakistan has wanted more, and the U.S, not really satisfied with the half-hearted support in Afghanistan, wasn't willing to grant it, largely due to the complex relationship between Afghanistan and Pakistan, who George Friedman describes as "one political entity, both sharing various ethnic groups and tribes, with the political border between them meaning very little (The Next Decade 107)". At the same time, the war itself is spilling over into Pakistan and threatening to destabilize the State itself, putting the Indo-Pakistani balance in a tenuous state (Friedman, The Next Decade 106). The alliance benefits neither party anymore (Friedman, GPF), and the war which has been carried out by means of the alliance is threatening to upset both countries' interests more than it serves them (VOA). The end of both the war and the alliance was virtually inevitable.

Enter, the Dragon

With the U.S. withdrawing from Afghanistan and disengaging from Pakistan, China's entry into the resulting vacuum was not even a question. Most of the world sees that it was a chance for China to expand their influence, but not everyone can see that it was also a desperate move to plug a dam previously plugged by the finger of the U.S. military. One aspect of China that is not commonly known in the West is that there is a vast region with a predominantly Muslim population: Xinjiang. This province (technically classified as a "semi-autonomous region," though I'm not sure what alleged autonomy they have) is on China's northwest side, bordered by India, Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and... you guessed it: Pakistan and Afghanistan. And the population there has never been happy with China's rule. It's not commonly known in the West for a lot of reasons, but the Uighurs have suffered similar treatment to the plight of the Tibetans (Radio Free Asia), so this population of angry Muslims put down by an outside force of "infidels" has become fertile ground lately for Jihadism, especially with the Taliban, Al-Qaeda and a few ISIS affiliates right across the border in Afghanistan.

Despite China's rhetoric about U.S. "interference" all over the world, they've reluctantly admitted that the U.S. presence in Afghanistan was a blessing for them, calling the U.S. "the most important external force in the region (Yang, Opinion of China 221) and even stating that it is "impossible" to foresee security in Afghanistan if the U.S. pulls out (Yang, 226). When the U.S. announced their intention to withdraw from afghanistan, China's response was one of uncertainty, and the Chinese government was not completely able to hide their sigh of relief over the decision to delay our withdrawal. The reason for this is because Afghanistan has always been a thorn in the side of the PLA brigades responsible for maintaining control in Xinjiang. Yang Mifen's Opinion of China emphasizes this repeatedly, stating "the security situation in Afghanistan directly influences the stability and development of Western China (226)," and "the turmoil and rising religious extremism in Afghanistan have always been potential threats to the stability of Xinjiang (234)."

In addition to the security threats, China foresees a very old, but very familiar problem. Just as bandits and so-called "barbarians" in this region, usually the Uzbek, made the ancient Silk Road dangerous, a chaotic security situation in Afghanistan or Pakistan would make China's "Belt and Road Initiative" nothing more than a dream (Yang, 226 & 227). We can turn once again to Yang's Opinion of China for a succinct summary of China's interests. "The situation has profound impacts on regional security and forms the biggest challenge against China's Belt and Road Initiative (214)."

As America began to disengage from the region, China could neither afford to take the chance of it destabilizing, nor pass up the opportunity to assert influence over it. Moving in was a no-brainer.

So America Lost Out, Right?

Well, in what way?

Think about it. What were America's objectives in this region, both in the Afghanistan War and in the alliance with Pakistan? Well, Friedman has our answer once again. "as we've noted, the United States has three principal interests there: to maintain a regional balance of power; to make certain that the flow of oil is not interrupted; and to defeat the Islamist groups centered there that threaten the United States (The Next Decade 105)" and "that is why over the next ten years the primary American strategy in this region must be to help create a strong and viable Pakistan (108)." Well, the best funds to spend on a project (and the best troops to send to their deaths against an enemy) are always someone else's. In short, those three interests (and the strategy Friedman suggests for achieving them) are served just as much by China being there as they are by the U.S. military being there, and we get these benefits without the need for the continued headache of a military occupation in a region no major power in history has ever been able to effectively control. China's "Belt and Road Initiative" includes massive investments in developing the "China Pakistan Economic Corridor (Yang 231)," which strengthens Pakistan. And again, the best part of this is that the money to do it is coming out of China's coffers and not ours; indeed, we've rid ourselves of $225 billion in annual aid to Pakistan. For America's purposes, what matters is that Pakistan is there as a counterweight to India. It fulfills that role as a Chinese vassal state just as effectively as it would if it remained a lukewarm American quasi-ally (Economic Times), and the resulting bitterness against Chinese Imperialism will serve our purposes in the 2020's smashingly, as I will outline in my upcoming entry about the lengthy list of nations who have had it with China throwing their weight around.

Militarily, the United States will not pull out of the region all at once because we can't afford to see the region in chaos and China's military is just not ready for the task of taking over yet {not only do they have minimal counterterrorism training but so far they have one small base under construction (Straits Times) in a panhandle of Afghanistan right across the border from China's Xinjiang and badly isolated from the rest of the country}, but China will not be willing to lose that all-important "face" by appearing weak. They'll pour troops into Afghanistan in droves, no matter the cost in blood or treasure, desperate to prove to their newfound Pakistani subjects that they are "bigger, stronger and more committed" than the U.S. was. Given that this (keeping Jihadic terror at bay) is one of the few areas where China's interests and America's interests overlap, it stands roughly to reason that the rate of China's advance into Afghanistan and the rate of the U.S.'s withdrawal will actually see some level of coordination, even if neither country admits it. Since the Jihadic extremists that are a headache for the U.S. are an even bigger headache for China, China will be just as interested in keeping those pests down as the U.S. has been, if not more so given that they are the one with a large population of Jihadic separatists within their own borders.

If there is country who has grounds to tremble as the dragon coils itself around Pakistan, it's India, and that trembling is sending her running right into the open arms of a nation she wasn't quite willing to cooperate with a few short years ago: the United States.

Good Golly, Miss Bolly!

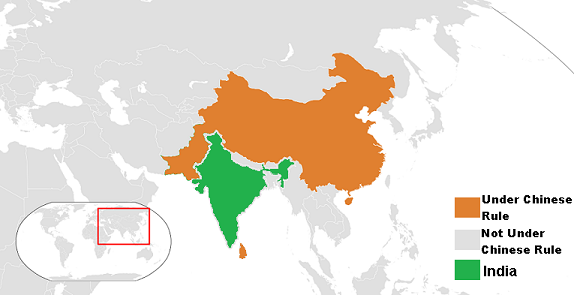

Right now, India is having what the American South calls a "conniption fit," and I'm sure you can see from this map exactly why. Between Pakistan becoming what many opponents of the CPEC are calling a "Chinese Colony," and China's takeover of Sri Lanka's main port, viewed by many as Sri Lanka's de facto submission to Chinese vassalage (Hindu International), India is watching their oldest enemy, China, closing in around them from every direction. For decades India has been bitter rivals with Pakistan, for millennia she has been on competition with China, and she has had more than her share of spats with Sri Lanka, but now, instead of having three separate enemies with three separate agendas, India faces a single hostile power on every side.

For our part, the U.S. has been trying to curry good relations with India (no pun intended) for some time for a lot of reasons, not the least of which is to try and incorporate them into the security framework of the Indo-Pacific region. Despite worries about China (a long-time rival with India, but separated from India by the formidable Himalayan Mountains), India, who has always had slightly different interests than the U.S, has always been somewhat wishy-washy on the subject. One of the main reasons was the U.S. alliance with India's other enemy, Pakistan.

Needless to say, that's one obstacle between US-India relations that no longer exists, and India has suddenly been very willing to participate in the nascent "Quad-Alliance" of The U.S, Japan, India and Australia.

So Let's Recap

The U.S. gets what we have sought from Central Asia.

China spends their money and bleeds their troops to accomplish it.

We don't have to.

India suddenly has a strong incentive to work with the West.

And as an added bonus, every Chinese military asset stuck in Afghanistan (and I anticipate that being a lot) is one that's NOT in the South Pacific. The region is volatile, draining, hard to get into, and hard to get out of. Meanwhile every U.S. military asset NOT stuck in Afghanistan is one that can go wherever else we need them, most likely the South Pacific.

Pakistan truly was the glass China couldn't allow to fall and break, the bait they couldn't refuse to take, and the trap they can't escape. For them, it was Strategy 12, take every chance to make any gain, no matter how small. For the U.S. it was a simple matter of Strategy 11; sacrificing the peach (a small asset in one region) to secure a plum (a more valuable advantage elsewhere). And the best part is even though the Chinese probably see what we're doing (the strategies demonstrated therein do have their origins in Ancient China), they have so much at stake in Central Asia that they have no choice but to commit to it anyway.

Hey China...

You wanted "a World with Chinese Characteristics."

You wanted "a new kind of Great Power Politics."

Well, how do you like them so far?

Works Cited

Books

Friedman, George. The Next Decade: Empire and Republic in a Changing World. New York: Random House Publishers, 2011.

(ISBN 978-0-3074-7639-5)

Moriya, Hiroshi. The 36 Strategies of the Martial Arts. Trans. William Scott Wilson. Boston: Shambala Publishers, 2013.

(ISBN 978-1-59030-992-6)

Sun-Tzu. The Art of War. Trans. John Minford. New York: Penguin Publishers, 2003.

(ISBN 978-0-14-043919-9)

Yang, Mifen. Opinion of China: Insight into International Hotspot Issues. Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2016.

(ISBN 978-7-300-24623-9)

From the Web

"Around 120,000 Uighurs Detained For Political Re-education in Xinjiang's Kashgar Prefecture." Radio Free Asia. 22 Jan. 2018. Web. 1 Feb. 2018.

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detentions-01222018171657.html

"China: After OBOR Gets Ready, Pakistan will Become China's Colony: S Akbar Zaidi." The Economic Times. India Times, 12 Jun 2017. Web. 8 Feb. 2018.

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/after-obor-gets-ready-pakistan-will-become-chinas-colony-s-akbar-zaidi/articleshow/59100114.cms

"China in Talks over Military Base in Remote Afghanistan: Officials." The Straits Times. SPH, 2 Feb. 2018. Web. 16 Feb. 2018.

http://www.straitstimes.com/world/middle-east/china-in-talks-over-military-base-in-remote-afghanistan-officials

"'Tempestuous' Defines US-Pakistan Alliance." VOA News. Voice of America, 3 Jan. 2018. Web. 14 Feb. 2018.

https://www.voanews.com/a/timeline-of-pakistan-and-us-relations/4190104.html

"Sri Lanka Formally Hands Over Hambantota Port on 99-year Lease to China." Hindu International. The Hindu, 9 Dec. 2017. Web. 29 Jan. 2018.

http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/sri-lanka-formally-hands-over-hambantota-port-on-99-year-lease-to-china/article21380382.ece

Friedman, George. "The End of the US-Pakistan Alliance." Geopolitical Futures. 8 Jan. 2018. Web. 12 Feb. 2018.

https://geopoliticalfutures.com/end-us-pakistan-alliance/