Local advocates blast proposed SNAP cuts

![U5dtg7j51WwcRyBRkJB5SCVdtwh17pY[1].gif](https://steemitimages.com/0x0/https://res.cloudinary.com/hpiynhbhq/image/upload/v1520789816/p5ygc6rqo7li4037x8nl.gif)

At a public listening session in Cobleskill this fall for the new federal farm bill, advocates for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program fought to make themselves heard among local farmers, pleading that no further cuts be made to the program.

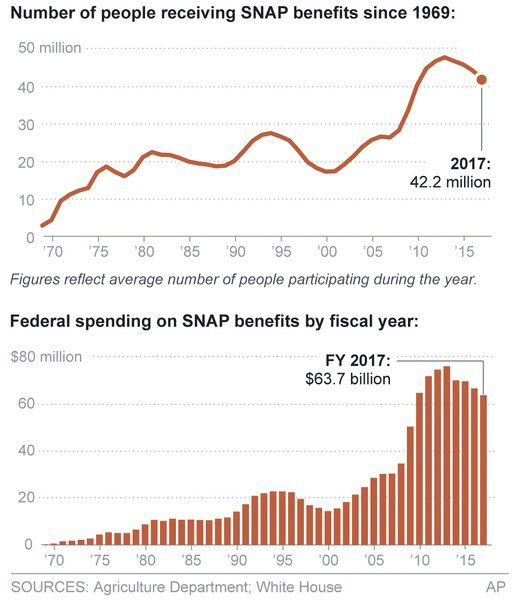

The 2014 comprehensive farm bill slashed $8 billion from SNAP, commonly known as food stamps. The current administration's proposed 2019 budget would cut the program by about 30 percent a year, totaling 1.4 billion in cuts each year and over $14 billion over 10 years in New York State alone.

Delivery of a “harvest box” containing shelf-stable groceries has been pitched to replace half of recipients' monthly benefits, which the USDA contends would save $129 billion over 10 years.

Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., vowed in a media release to push Congress to reject the cuts, calling SNAP a lifeline for many New Yorkers.

“I'm a survivor all my life, so whatever they give me I'll make do,” said 79-year-old Wayne Roseboom, who has lived in Oneonta for 36 years. He said that Otsego County's Office for the Aging signed him up for food stamps and that he uses them to shop at Hannaford Supermarket. He saves money by having dinner most nights at The Lord's Table, a community feeding ministry of St. James Church, which also includes a food bank.

Joanne Roberts, who was also eating dinner at The Lord's Table on Monday, said that she has had SNAP since she moved to the area from Yonkers nearly three years ago. She said she receives $65 in food credits a month.

“It's not enough,” said the 56-year-old, who also receives disability benefits for sciatica, a nerve condition.

SNAP recipients can buy groceries with an automatically refilled card that is accepted at many supermarkets. Hot food and any nonfood items such as household supplies or medicine are not included, nor are liquor or tobacco products. Individual benefits are based on income and household size.

“They issue petty sanctions over small things. Then there's the need for this,” 31-year-old Jacob Fink said at the charity dinner, referring to Otsego County's Department of Social Services. He said that he has no income and has gone without SNAP for two months after being told that his benefits were being transferred from Montgomery County.

Otsego County had 3,140 total SNAP cases in 2017, up from 3,027 the previous year, according to Deborah Currie, DSS director of Income Maintenance. Delaware County DSS did not respond to a request for its number of cases by press time.

A report released in February by the Washington, D.C-based Urban Institute found that the maximum SNAP benefit did not cover the cost of a low-income meal in 99 percent of U.S. continental counties. Delaware County fell among the 10 percent with the largest gap. A low-income meal costs an average of $2.92, 57 percent more than the maximum SNAP benefit per meal of $1.86. Otsego County matched the national average meal cost of $2.36. On a monthly basis, benefits fall short of the the cost of an average meal by $46.50 a person.

While the program is intended to supplement a family's food budget, 37 percent of SNAP households have zero net income.

“Most everyone in the building does receive food stamps,” tenant relations specialist Jennifer Beams said of the roughly 120 residents of Nader Towers, Section 8 housing owned by the city of Oneonta. A county-funded meal program offers lunch to residents, but they are otherwise on their own, she said. Those who can't shop for themselves may have home-delivered meals from the Office for the Aging or other programs.

Catholic Charities nutrition outreach and education program coordinator Ron Rovetto assists people with signing up for SNAP benefits and reviewed the participation requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents. After three months, recipients must provide proof that they work, volunteer or are looking for work at least 20 hours a week. Rovetto said he has had a steady increase in referrals since his program started six years ago. Most people he assists work or have unearned income such as Social Security or disability.

“Despite the fact that the economy has improved in some ways, particularly in Otsego County it's not that great,” he said. “People will always be eligible because the cost of living is so high.”

The state stepped in to preserve $457 million in benefits a year after the federal government cut SNAP in its 2014 farm bill, and Rovetto said he hopes it will do the same if further cuts go through this time.

With the federal government tightening its belt, community responses to food insecurity and poverty are as vital as ever. Cynthia Walton-Leavitt, pastor of First United Presbyterian Church in Oneonta, began a county hunger coalition beginning with a task force in 2011. The network mainly shares information and ideas, she said, and has sought to list all local food resources on its website, otsegohunger.com

“We're all concerned with people in poverty and how they can be lifted,” she said. “Our concern as a group is that we ought to be supporting SNAP and other programs like it.”

A “Poverty to Prosperity” summit offered Wednesday took stock of the current state of local poverty, formed teams for a future Opportunity Conference and shared language, beliefs and attitudes that could be changed to break barriers. The event was presented by the Empire State Poverty Reduction Initiative in partnership with the city of Oneonta and Opportunities for Otsego at Foothills Performing Arts and Civic Center.

![U5dtg7j51WwcRyBRkJB5SCVdtwh17pY[1].gif](https://steemitimages.com/0x0/https://res.cloudinary.com/hpiynhbhq/image/upload/v1520789855/lvg2jylxznnbotncxezw.gif)