THE GREATEST ROCK ALBUMS OF ALL TIME

Music is a very personal thing, and this is a list of my own favourite albums, rather than a definitive list of music history.

All the descriptions here are copied from the music site All Music

The only original thing about this list is that it’s sorted by year. (Apart from the fact that it’s the best list of albums ever compiled!)

My guess before starting this post was that my favourite albums nearly all came out in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s, with the peak era of awesomeness being 1977 to 1997. And that there would be very few albums from this century.

This is because modern music sucks and here is why -

1967 THE JIMI HENDRIX EXPERIENCE – ARE YOU EXPERIENCED?

One of the most stunning debuts in rock history, and one of the definitive albums of the psychedelic era. On Are You Experienced?, Jimi Hendrix synthesized various elements of the cutting edge of 1967 rock into music that sounded both futuristic and rooted in the best traditions of rock, blues, pop, and soul. It was his mind-boggling guitar work, of course, that got most of the ink, building upon the experiments of British innovators like Jeff Beck and Pete Townshend to chart new sonic territories in feedback, distortion, and sheer volume. It wouldn’t have meant much, however, without his excellent material, whether psychedelic frenzy (“Foxey Lady,” “Manic Depression,” “Purple Haze”), instrumental freak-out jams (“Third Stone from the Sun”), blues (“Red House,” “Hey Joe”), or tender, poetic compositions (“The Wind Cries Mary”) that demonstrated the breadth of his songwriting talents. Not to be underestimated were the contributions of drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding, who gave the music a rhythmic pulse that fused parts of rock and improvised jazz. Many of these songs are among Hendrix‘s very finest; it may be true that he would continue to develop at a rapid pace throughout the rest of his brief career, but he would never surpass his first LP in terms of consistently high quality.

1969 LED ZEPPELIN

Led Zeppelin had a fully formed, distinctive sound from the outset, as their eponymous debut illustrates. Taking the heavy, distorted electric blues of Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, and Cream to an extreme, Zeppelin created a majestic, powerful brand of guitar rock constructed around simple, memorable riffs and lumbering rhythms. But the key to the group’s attack was subtlety: it wasn’t just an onslaught of guitar noise, it was shaded and textured, filled with alternating dynamics and tempos. As Led Zeppelin proves, the group was capable of such multi-layered music from the start.

Although the extended psychedelic blues of “Dazed and Confused,” “You Shook Me,” and “I Can’t Quit You Baby” often gather the most attention, the remainder of the album is a better indication of what would come later. “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You” shifts from folky verses to pummeling choruses; “Good Times Bad Times” and “How Many More Times” have groovy, bluesy shuffles; “Your Time Is Gonna Come” is an anthemic hard rocker; “Black Mountain Side” is pure English folk; and “Communication Breakdown” is a frenzied rocker with a nearly punkish attack. Although the album isn’t as varied as some of their later efforts, it nevertheless marked a significant turning point in the evolution of hard rock and heavy metal.

1969 LED ZEPPELIN 2

Recorded quickly during Led Zeppelin‘s first American tours, Led Zeppelin II provided the blueprint for all the heavy metal bands that followed it. Since the group could only enter the studio for brief amounts of time, most of the songs that compose II are reworked blues and rock & roll standards that the band was performing on-stage at the time. Not only did the short amount of time result in a lack of original material, it made the sound more direct. Jimmy Page still provided layers of guitar overdubs, but the overall sound of the album is heavy and hard, brutal and direct. “Whole Lotta Love,” “The Lemon Song,” and “Bring It on Home” are all based on classic blues songs — only, the riffs are simpler and louder and each song has an extended section for instrumental solos. Of the remaining six songs, two sport light acoustic touches (“Thank You,” “Ramble On”), but the other four are straight-ahead heavy rock that follows the formula of the revamped blues songs. While Led Zeppelin II doesn’t have the eclecticism of the group’s debut, it’s arguably more influential. After all, nearly every one of the hundreds of Zeppelin imitators used this record, with its lack of dynamics and its pummeling riffs, as a blueprint.

1970 THE WHO – LIVE AT LEADS

Rushed out in 1970 as a way to bide time as the Who toiled away on their follow-up to Tommy, Live at Leeds wasn’t intended to be the definitive Who live album, and many collectors maintain that the band had better shows available on bootlegs. But those shows weren’t easily available whereas Live at Leeds was, and even if this show may not have been the absolute best, it’s so damn close to it that it would be impossible for anybody but aficionados to argue. Here, the Who sound vicious — as heavy as Led Zeppelin but twice as volatile — as they careen through early classics with the confidence of a band that had finally achieved acclaim but had yet to become preoccupied with making art. In that regard, this recording — in its many different forms — may have been perfectly timed in terms of capturing the band at a pivotal moment in its history.

There is certainly no better record of how this band was a volcano of violence on-stage, teetering on the edge of chaos but never blowing apart. This was most true on the original LP, which was a trim six tracks, three of them covers (“Young Man Blues,” “Summertime Blues,” “Shakin’ All Over”) and three originals from the mid-’60s, two of those (“Substitute,” “My Generation”) vintage parts of their repertory and only “Magic Bus” representing anything resembling a recent original, with none bearing a trace of their mod roots. This was pure, distilled power, all the better for its brevity; throughout the ’70s the album was seen as one of the gold standards in live rock & roll, and certainly it had a fury that no proper Who studio album achieved. It was also notable as one of the earliest legitimate albums to implicitly acknowledge — and go head to head with — the existence of bootleg LPs. Indeed, its very existence owed something to the efforts of Pete Townshend and company to stymie the bootleggers.

The Who had made extensive recordings of performances along their 1969 tour, with the intention of preparing a live album from that material, but they recognized when it was over that none of them had the time or patience to go through the many dozens of hours of live performances in order to sort out what to use for the proposed album. According to one account, the band destroyed those tapes in a massive bonfire, so that none of the material would ever surface without permission. They then decided to go to the other extreme in preparing a live album, scheduling this concert at Leeds University and arranging the taping, determined to do enough that was worthwhile at the one show. As it turned out, even here they generated an embarrassment of riches — the band did all of Tommy, as audiences of the time would have expected (and, indeed, demanded), but as the opera was already starting to feel like an albatross hanging around the collective neck of the band (and especially Townshend), they opted to leave out any part of their most famous work apart from a few instrumental strains in one of the jams. Instead, the original LP was limited to the six tracks named, and that was more than fine as far as anyone cared.

And fans who bought the LP got a package of extra treats for their money. The album’s plain brown sleeve was, itself, a nod and nudge to the bootleggers, resembling the packaging of such early underground LP classics as the Bob Dylan Great White Wonder set and the Rolling Stones concert bootleg Liver Than You’ll Ever Be, from the latter group’s 1969 tour — and it was a sign of just how far the Who had come in just two years that they could possibly (and correctly) equate interest in their work as being on a par with Dylan and the Stones. But Live at Leeds‘ jacket was a fold-out sleeve with a pocket that contained a package of memorabilia associated with the band, including a really cool poster, copies of early contracts, etc. It was, along with Tommy, the first truly good job of packaging for this band ever to come from Decca Records; the label even chose to forgo the presence of its rainbow logo, carrying the bootleg pose to the plain label and handwritten song titles, and the note about not correcting the clicks and pops. At the time, you just bought this as a fan, but looking back 30 or 40 years on, those now seem to be quietly heady days for the band (and for fans who had supported them for years), finally seeing the music world and millions of listeners catch up.

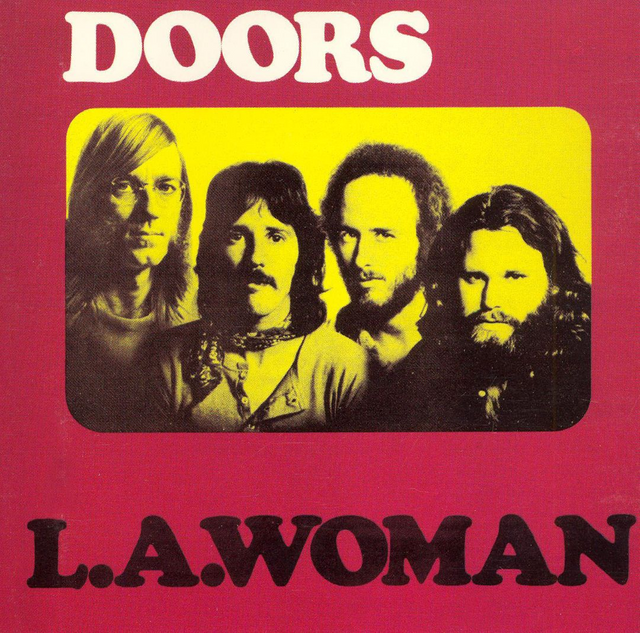

1971 THE DOORS – LA WOMAN

The final album with Jim Morrison in the lineup is by far their most blues-oriented, and the singer’s poetic ardor is undiminished, though his voice sounds increasingly worn and craggy on some numbers. Actually, some of the straight blues items sound kind of turgid, but that’s more than made up for by several cuts that rate among their finest and most disturbing work. The seven-minute title track was a car-cruising classic that celebrated both the glamour and seediness of Los Angeles; the other long cut, the brooding, jazzy “Riders on the Storm,” was the group at its most melodic and ominous. It and the far bouncier “Love Her Madly” were hit singles, and “The Changeling” and “L’America” count as some of their better little-heeded album tracks. An uneven but worthy finale from the original quartet.

1975 LED ZEPPELIN – PHYSICAL GRAFFITI

Led Zeppelin returned from a nearly two-year hiatus in 1975 with the double-album Physical Graffiti, their most sprawling and ambitious work. Where Led Zeppelin IV and Houses of the Holy integrated influences on each song, the majority of the tracks on Physical Graffiti are individual stylistic workouts. The highlights are when Zeppelin incorporate influences and stretch out into new stylistic territory, most notably on the tense, Eastern-influenced “Kashmir.” “Trampled Underfoot,” with John Paul Jones‘ galloping keyboard, is their best funk-metal workout, while “Houses of the Holy” is their best attempt at pop, and “Down by the Seaside” is the closest they’ve come to country. Even the heavier blues — the 11-minute “In My Time of Dying,” the tightly wound “Custard Pie,” and the monstrous epic “The Rover” — are louder and more extended and textured than their previous work. Also, all of the heavy songs are on the first record, leaving the rest of the album to explore more adventurous territory, whether it’s acoustic tracks or grandiose but quiet epics like the affecting “Ten Years Gone.” The second half of Physical Graffiti feels like the group is cleaning the vaults out, issuing every little scrap of music they set to tape in the past few years. That means that the album is filled with songs that aren’t quite filler, but don’t quite match the peaks of the album, either. Still, even these songs have their merits — “Sick Again” is the meanest, most decadent rocker they ever recorded, and the folky acoustic rock & roll of “Boogie with Stu” and “Black Country Woman” may be tossed off, but they have a relaxed, off-hand charm that Zeppelin never matched. It takes a while to sort out all of the music on the album, but Physical Graffiti captures the whole experience of Led Zeppelin at the top of their game better than any of their other albums

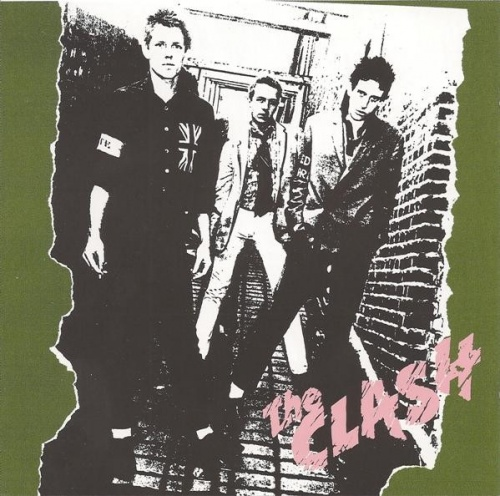

1977 THE CLASH

Never Mind the Bollocks may have appeared revolutionary, but the Clash‘s eponymous debut album was pure, unadulterated rage and fury, fueled by passion for both rock & roll and revolution. Though the cliché about punk rock was that the bands couldn’t play, the key to the Clash is that although they gave that illusion, they really could play — hard. The charging, relentless rhythms, primitive three-chord rockers, and the poor sound quality give the album a nervy, vital energy. Joe Strummer‘s slurred wails perfectly compliment the edgy rock, while Mick Jones‘ clearer singing and charged guitar breaks make his numbers righteously anthemic. Even at this early stage, the Clash were experimenting with reggae, most notably on the Junior Murvin cover “Police & Thieves” and the extraordinary “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais,” which was one of five tracks added to the American edition of The Clash. “Deny,” “Protex Blue,” “Cheat,” and “48 Hours” were removed from the British edition and replaced for the U.S. release with the British-only singles “Complete Control,” “(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais,” “Clash City Rockers,” “I Fought the Law,” and “Jail Guitar Doors,” all of which were stronger than the items they replaced. Though the sequencing and selection were slightly different, the core of the album remained the same, and each song retained its power individually. Few punk songs expressed anger quite as bracingly as “White Riot,” “I’m So Bored with the U.S.A.,” “Career Opportunities,” and “London’s Burning,” and their power is all the more incredible today. Rock & roll is rarely as edgy, invigorating, and sonically revolutionary as The Clash.

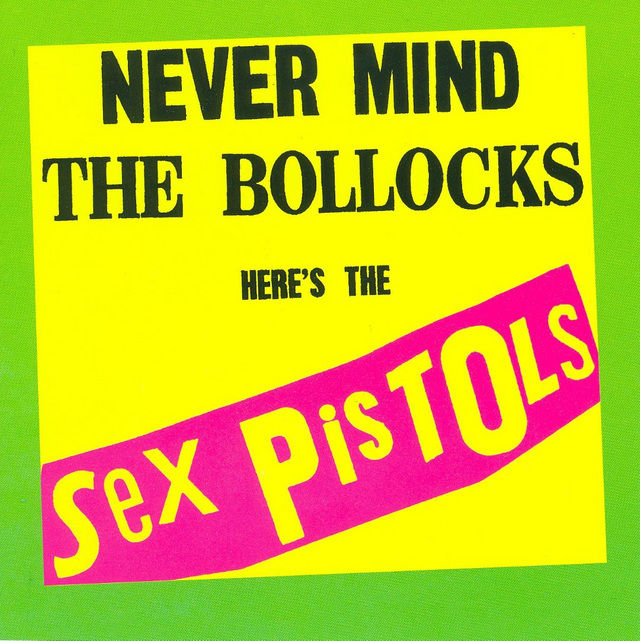

1977 THE SEX PISTOLS – NEVER MIND THE BOLLOCKS

While mostly accurate, dismissing Never Mind the Bollocks as merely a series of loud, ragged midtempo rockers with a harsh, grating vocalist and not much melody would be a terrible error. Already anthemic songs are rendered positively transcendent by Johnny Rotten‘s rabid, foaming delivery. His bitterly sarcastic attacks on pretentious affectation and the very foundations of British society were all carried out in the most confrontational, impolite manner possible. Most imitators of the Pistols‘ angry nihilism missed the point: underneath the shock tactics and theatrical negativity were social critiques carefully designed for maximum impact. Never Mind the Bollocks perfectly articulated the frustration, rage, and dissatisfaction of the British working class with the establishment, a spirit quick to translate itself to strictly rock & roll terms. The Pistols paved the way for countless other bands to make similarly rebellious statements, but arguably none were as daring or effective. It’s easy to see how the band’s roaring energy, overwhelmingly snotty attitude, and Rotten‘s furious ranting sparked a musical revolution, and those qualities haven’t diminished one bit over time. Never Mind the Bollocks is simply one of the greatest, most inspiring rock records of all time.

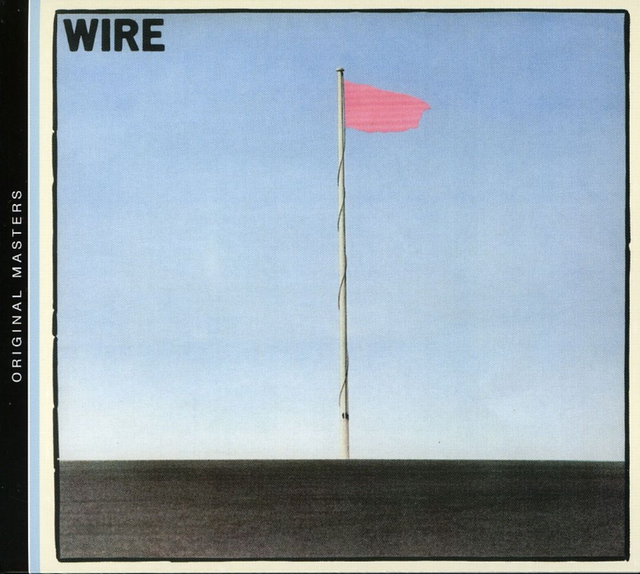

1977 WIRE -PINK FLAG

Perhaps the most original debut album to come out of the first wave of British punk, Wire‘s Pink Flag plays like The Ramones Go to Art School — song after song careens past in a glorious, stripped-down rush. However, unlike the Ramones, Wire ultimately made their mark through unpredictability. Very few of the songs followed traditional verse/chorus structures — if one or two riffs sufficed, no more were added; if a musical hook or lyric didn’t need to be repeated, Wire immediately stopped playing, accounting for the album’s brevity (21 songs in under 36 minutes on the original version). The sometimes dissonant, minimalist arrangements allow for space and interplay between the instruments; Colin Newman isn’t always the most comprehensible singer, but he displays an acerbic wit and balances the occasional lyrical abstraction with plenty of bile in his delivery. Many punk bands aimed to strip rock & roll of its excess, but Wire took the concept a step further, cutting punk itself down to its essence and achieving an even more concentrated impact. Some of the tracks may seem at first like underdeveloped sketches or fragments, but further listening demonstrates that in most cases, the music is memorable even without the repetition and structure most ears have come to expect — it simply requires a bit more concentration. And Wire are full of ideas; for such a fiercely minimalist band, they display quite a musical range, spanning slow, haunting texture exercises, warped power pop, punk anthems, and proto-hardcore rants — it’s recognizable, yet simultaneously quite unlike anything that preceded it. Pink Flag‘s enduring influence pops up in hardcore, post-punk, alternative rock, and even Brit-pop, and it still remains a fresh, invigorating listen today: a fascinating, highly inventive rethinking of punk rock and its freedom to make up your own rules.

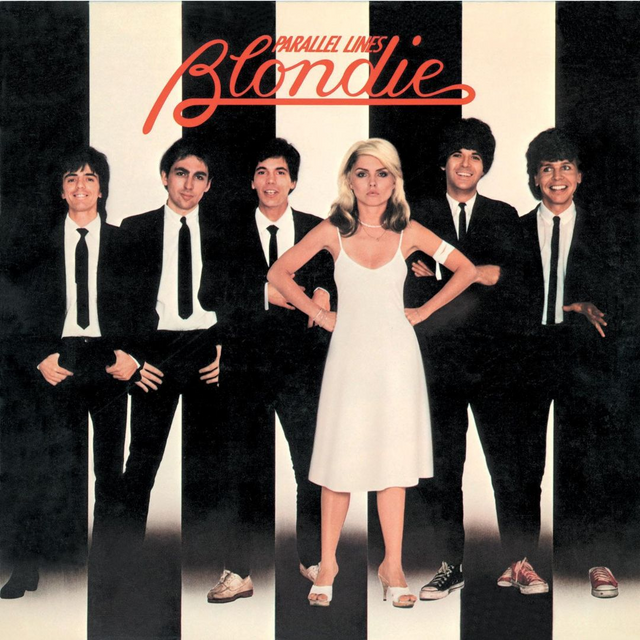

1978 BLONDIE – PARALLEL LINES

Blondie turned to British pop producer Mike Chapman for their third album, on which they abandoned any pretensions to new wave legitimacy (just in time, given the decline of the new wave) and emerged as a pure pop band. But it wasn’t just Chapman that made Parallel Lines Blondie‘s best album; it was the band’s own songwriting, including Deborah Harry, Chris Stein, and James Destri‘s “Picture This,” and Harry and Stein‘s “Heart of Glass,” and Harry and new bass player Nigel Harrison‘s “One Way or Another,” plus two contributions from nonbandmember Jack Lee, “Will Anything Happen?” and “Hanging on the Telephone.” That was enough to give Blondie a number one on both sides of the Atlantic with “Heart of Glass” and three more U.K. hits, but what impresses is the album’s depth and consistency — album tracks like “Fade Away and Radiate” and “Just Go Away” are as impressive as the songs pulled for singles. The result is state-of-the-art pop/rock circa 1978, with Harry‘s tough-girl glamour setting the pattern that would be exploited over the next decade by a host of successors led by Madonna.

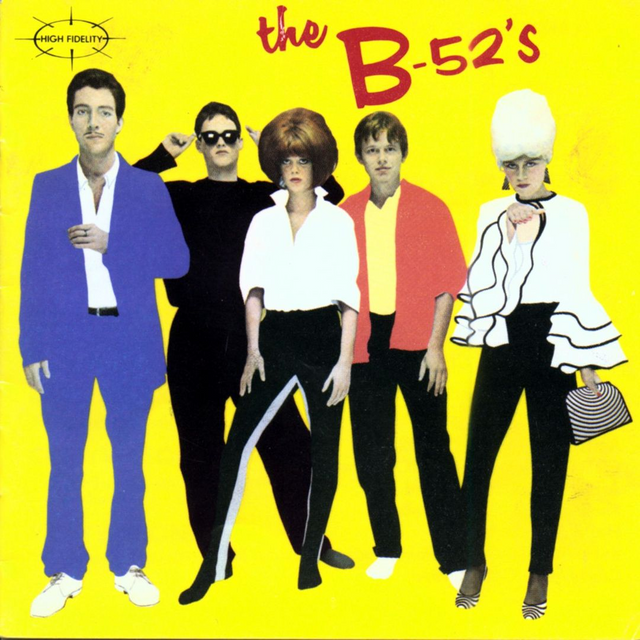

1979 THE B52’S

Even in the weird, quirky world of new wave and post-punk in the late ’70s, the B-52’s‘ eponymous debut stood out as an original. Unabashed kitsch mavens at a time when their peers were either vulgar or stylish, the Athens quintet celebrated all the silliest aspects of pre-Beatles pop culture — bad hairdos, sci-fi nightmares, dance crazes, pastels, and anything else that sprung into their minds — to a skewed fusion of pop, surf, avant-garde, amateurish punk, and white funk. On paper, it sounds like a cerebral exercise, but it played like a party. The jerky, angular funk was irresistibly danceable, winning over listeners dubious of Kate Pierson and Cindy Wilson‘s high-pitched, shrill close harmonies and Fred Schneider‘s campy, flamboyant vocalizing, pitched halfway between singing and speaking. It’s all great fun, but it wouldn’t have resonated throughout the years if the group hadn’t written such incredibly infectious, memorable tunes as “Planet Claire,” “Dance This Mess Around,” and, of course, their signature tune, “Rock Lobster.” These songs illustrated that the B-52’s‘ adoration of camp culture wasn’t simply affectation — it was a world view capable of turning out brilliant pop singles and, in turn, influencing mainstream pop culture. It’s difficult to imagine the endless kitschy retro fads of the ’80s and ’90s without the B-52’s pointing the way, but The B-52’s isn’t simply an historic artifact — it’s a hell of a good time.

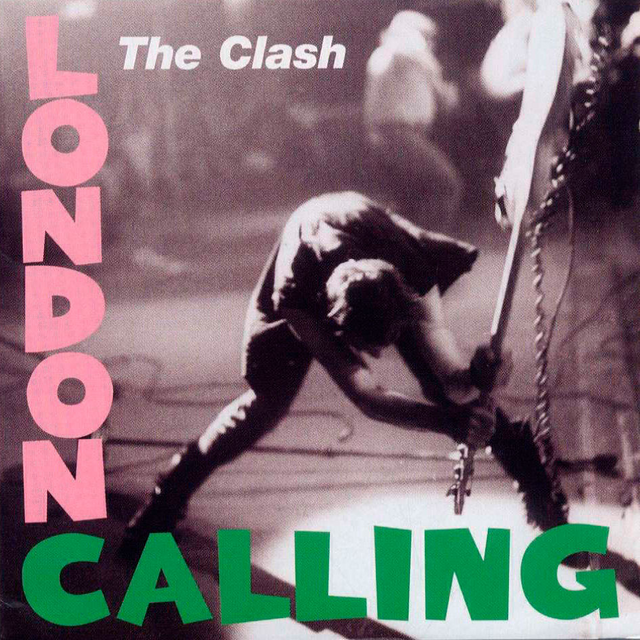

1979 THE CLASH – LONDON CALLING

Give ‘Em Enough Rope, for all of its many attributes, was essentially a holding pattern for the Clash, but the double-album London Calling is a remarkable leap forward, incorporating the punk aesthetic into rock & roll mythology and roots music. Before, the Clash had experimented with reggae, but that was no preparation for the dizzying array of styles on London Calling. There’s punk and reggae, but there’s also rockabilly, ska, New Orleans R&B, pop, lounge jazz, and hard rock; and while the record isn’t tied together by a specific theme, its eclecticism and anthemic punk function as a rallying call. While many of the songs — particularly “London Calling,” “Spanish Bombs,” and “The Guns of Brixton” — are explicitly political, by acknowledging no boundaries the music itself is political and revolutionary. But it is also invigorating, rocking harder and with more purpose than most albums, let alone double albums. Over the course of the record, Joe Strummer and Mick Jones (and Paul Simonon, who wrote “The Guns of Brixton”) explore their familiar themes of working-class rebellion and anti-establishment rants, but they also tie them in to old rock & roll traditions and myths, whether it’s rockabilly greasers or “Stagger Lee,” as well as mavericks like doomed actor Montgomery Clift. The result is a stunning statement of purpose and one of the greatest rock & roll albums ever recorded.

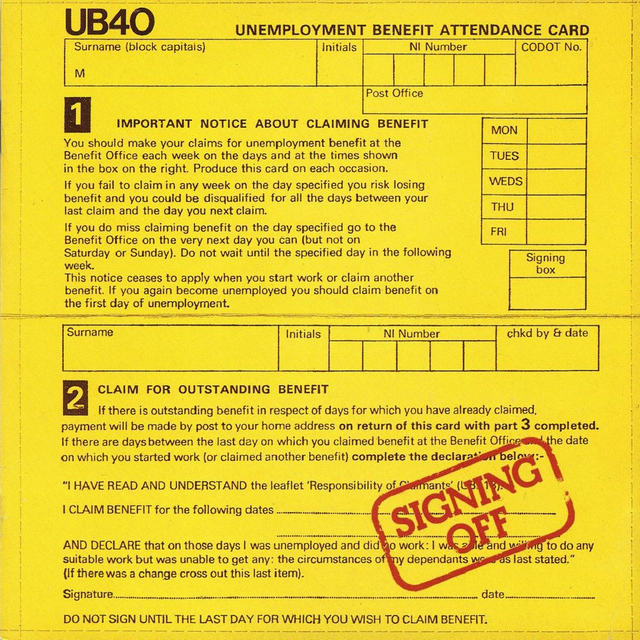

1980 UB40 - Signing Off

So ubiquitous was UB40's grip on the pop-reggae market that it may have been difficult for younger fans to comprehend just how their arrival shook up the British musical scene. They appeared just as 2 Tone had peaked and was beginning its slide towards oblivion. Not that it mattered, as few would try to shoehorn the band into that suit. However, the group was no more comfortable within the U.K. reggae axis of Steel Pulse, Aswad, and Matumbi. Their rhythms may have been reggae-based, their music Jamaican-inspired, but UB40 had such an original take on the genre that all comparisons were moot. Even their attack on the singles chart was unusual, as they smacked three double-A-sided singles into the Top Ten in swift succession. By rights, the second 45 should have acted as a taster for their album (it didn't, coming several months too soon), while the third should have been a spinoff (it wasn't, boasting two new songs entirely). Regardless, both sides of their debut single -- the roots-rocking indictment of politicians' refusal to relieve famine on "Food for Thought" and the dreamy tribute to Martin Luther "King" -- were included, as well as their phenomenal cover of Randy Newman's "I Think It's Going to Rain Today" off their second single. The new material was equally strong. The moody roots-fired "Tyler," which kicks off the set, is a potent condemnation of the U.S. judicial system, while its stellar dub, "25%," appears later in the set. The smoky Far Eastern-flavored "Burden" explores the dual tugs of national pride and shame over Britain's oppressive past (and present). If that was a thoughtful number, "Little by Little" was a blatant call for class warfare. Of course, Ali Campbell never raised his voice -- he didn't need to. His words were his sword, and the creamier and sweeter his delivery, the deeper they cut. Their music was just as revolutionary, their sound unlike anything else on either island, from deep dubs shot through with jazzy sax to the bright and breezy instrumental "12 Bar," with its splendid loose groove transmuted later in the set to the jazzier and smokier "Adella." Meanwhile, "Food" slams into the dance clubs, and "King" floats to the heavens. It's hard to believe this is the same UB40 that later topped the U.K. charts with the likes of "Red Red Wine" and "I've Got You Babe." Their fire was dampened quickly, but on Signing Off it blazed high, still accessible to the pop market, but so edgy that even those who are sure there's nothing about the group to admire will change their tune instantly.

1986 BEASTIE BOYS – LICENSED TO ILL

Perhaps Licensed to Ill was inevitable — a white group blending rock and rap, giving them the first number one album in hip-hop history. But that reading of the album’s history gives short shrift to the Beastie Boys; producer Rick Rubin, and his label, Def Jam, and this remarkable record, since mixing metal and hip-hop isn’t necessarily an easy thing to do.

Just sampling and scratching Sabbath and Zeppelin to hip-hop beats does not make for an automatically good record, though there is a visceral thrill to hearing those muscular riffs put into overdrive with scratching. But, much of that is due to the producing skills of Rick Rubin, a metalhead who formed Def Jam Records with Russell Simmons and had previously flirted with this sound on Run-D.M.C.‘s Raising Hell, not to mention a few singles and one-offs with the Beasties prior to this record.

He made rap rock, but to give him lone credit for Licensed to Ill (as some have) is misleading, since that very same combination would not have been as powerful, nor would it have aged so well — aged into a rock classic — if it weren’t for the Beastie Boys, who fuel this record through their passion for subcultures, pop culture, jokes, and the intoxicating power of wordplay.

At the time, it wasn’t immediately apparent that their obnoxious patter was part of a persona (a fate that would later plague Eminem), but the years have clarified that this was a joke — although, listening to the cajoling rhymes, filled with clear parodies and absurdities, it’s hard to imagine the offense that some took at the time. Which, naturally, is the credit of not just the music — they don’t call it the devil’s music for nothing — but the wild imagination of the Beasties, whose rhymes sear into consciousness through their gonzo humor and gleeful delivery.

There hasn’t been a funnier, more infectious record in pop music than this, and it’s not because the group is mocking rappers (in all honesty, the truly twisted barbs are hurled at frat boys and lager lads), but because they’ve already created their own universe and points of reference, where it’s as funny to spit out absurdist rhymes and pound out “Fight for Your Right (To Party)” as it is to send up street corner doo wop with “Girls.” Then, there is the overpowering loudness of the record — operating from the axis of where metal, punk, and rap meet, there never has been a record this heavy and nimble, drunk on its own power yet giddy with what they’re getting away with.

There is a sense of genuine discovery, of creating new music, that remains years later, after countless plays, countless misinterpretations, countless rip-off acts, even countless apologies from the Beasties, who seemed guilty by how intoxicating the sound of it is, how it makes beer-soaked hedonism sound like the apogee of human experience. And maybe it is, maybe it isn’t, but in either case, Licensed to Ill reigns tall among the greatest records of its time.

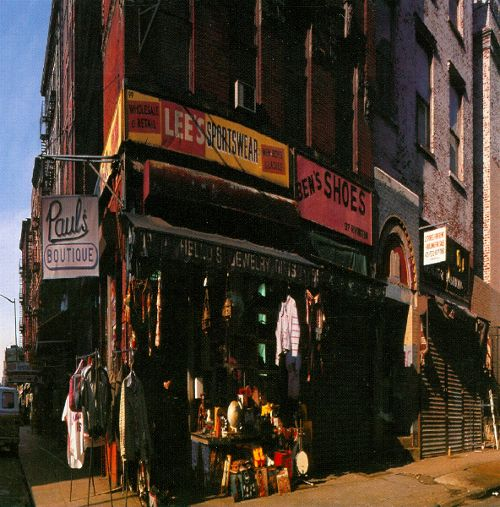

1989 BEASTIE BOYS – PAUL’S BOUTIQUE

Such was the power of Licensed to Ill that everybody, from fans to critics, thought that not only could the Beastie Boys not top the record, but that they were destined to be a one-shot wonder. These feelings were only amplified by their messy, litigious departure from Def Jam and their flight from their beloved New York to Los Angeles, since it appeared that the Beasties had completely lost the plot.

Many critics in fact thought that Paul’s Boutique was a muddled mess upon its summer release in 1989, but that’s the nature of the record — it’s so dense, it’s bewildering at first, revealing its considerable charms with each play. To put it mildly, it’s a considerable change from the hard rock of Licensed to Ill, shifting to layers of samples and beats so intertwined they move beyond psychedelic; it’s a painting with sound. Paul’s Boutique is a record that only could have been made in a specific time and place. Like the Rolling Stones in 1972, the Beastie Boys were in exile and pining for their home, so they made a love letter to downtown New York — which they could not have done without the Dust Brothers, a Los Angeles-based production duo who helped redefine what sampling could be with this record.

Sadly, after Paul’s Boutique sampling on the level of what’s heard here would disappear; due to a series of lawsuits, most notably Gilbert O’Sullivan‘s suit against Biz Markie, the entire enterprise too cost-prohibitive and risky to perform on such a grand scale. Which is really a shame, because if ever a record could be used as incontrovertible proof that sampling is its own art form, it’s Paul’s Boutique.

Snatches of familiar music are scattered throughout the record — anything from Curtis Mayfield‘s “Superfly” and Sly Stone‘s “Loose Booty” to Loggins & Messina‘s “Your Mama Don’t Dance” and the Ramones‘ “Suzy Is a Headbanger” — but never once are they presented in lazy, predictable ways. The Dust Brothers and Beasties weave a crazy-quilt of samples, beats, loops, and tricks, which creates a hyper-surreal alternate reality — a romanticized, funhouse reflection of New York where all pop music and culture exist on the same strata, feeding off each other, mocking each other, evolving into a wholly unique record, unlike anything that came before or after.

It very well could be that its density is what alienated listeners and critics at the time; there is so much information in the music and words that it can seem impenetrable at first, but upon repeated spins it opens up slowly, assuredly, revealing more every listen. Musically, few hip-hop records have ever been so rich; it’s not just the recontextulations of familiar music via samples, it’s the flow of each song and the album as a whole, culminating in the widescreen suite that closes the record.

Lyrically, the Beasties have never been better — not just because their jokes are razor-sharp, but because they construct full-bodied narratives and evocative portraits of characters and places. Few pop records offer this much to savor, and if Paul’s Boutique only made a modest impact upon its initial release, over time its influence could be heard through pop and rap, yet no matter how its influence was felt, it stands alone as a record of stunning vision, maturity, and accomplishment. Plus, it’s a hell of a lot of fun, no matter how many times you’ve heard it.

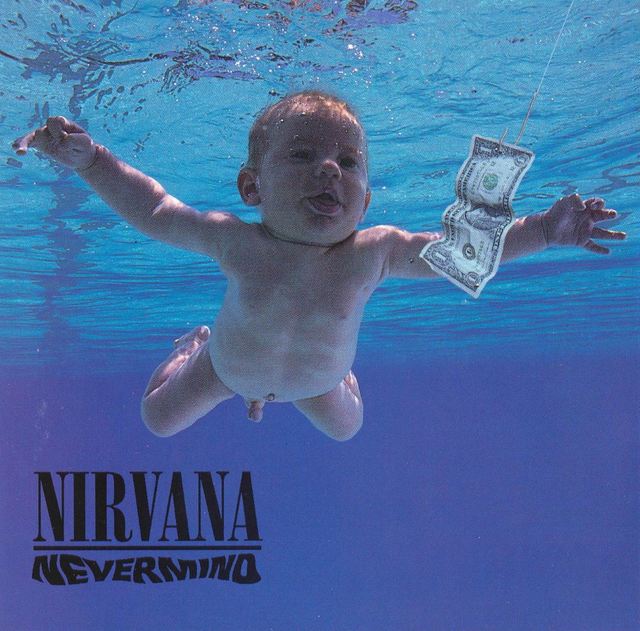

1991 NIRVANA – NEVERMIND

Nevermind was never meant to change the world, but you can never predict when the Zeitgeist will hit, and Nirvana‘s second album turned out to be the place where alternative rock crashed into the mainstream. This wasn’t entirely an accident, either, since Nirvana did sign with a major label, and they did release a record with a shiny surface, no matter how humongous the guitars sounded. And, yes, Nevermind is probably a little shinier than it should be, positively glistening with echo and fuzzbox distortion, especially when compared with the black-and-white murk of Bleach. This doesn’t discount the record, since it’s not only much harder than any mainstream rock of 1991, its character isn’t on the surface, it’s in the exhilaratingly raw music and haunting songs. Kurt Cobain‘s personal problems and subsequent suicide naturally deepen the dark undercurrents, but no matter how much anguish there is on Nevermind, it’s bracing because he exorcizes those demons through his evocative wordplay and mangled screams — and because the band has a tremendous, unbridled power that transcends the pain, turning into pure catharsis. And that’s as key to the record’s success as Cobain‘s songwriting, since Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl help turn this into music that is gripping, powerful, and even fun (and, really, there’s no other way to characterize “Territorial Pissings” or the surging “Breed”). In retrospect, Nevermind may seem a little too unassuming for its mythic status — it’s simply a great modern punk record — but even though it may no longer seem life-changing, it is certainly life-affirming, which may just be better.

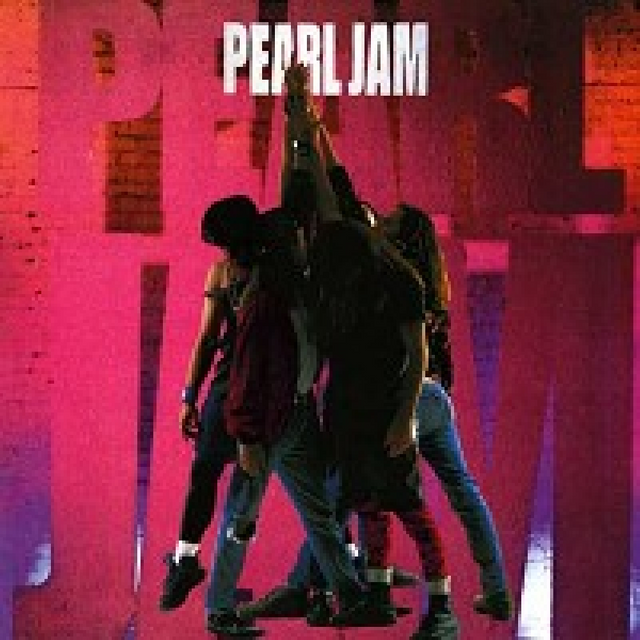

1991 PEARL JAM – TEN

Nirvana‘s Nevermind may have been the album that broke grunge and alternative rock into the mainstream, but there’s no underestimating the role that Pearl Jam‘s Ten played in keeping them there. Nirvana‘s appeal may have been huge, but it wasn’t universal; rock radio still viewed them as too raw and punky, and some hard rock fans dismissed them as weird misfits. In retrospect, it’s easy to see why Pearl Jam clicked with a mass audience — they weren’t as metallic as Alice in Chains or Soundgarden, and of Seattle’s Big Four, their sound owed the greatest debt to classic rock. With its intricately arranged guitar textures and expansive harmonic vocabulary, Ten especially recalled Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin. But those touchstones might not have been immediately apparent, since — aside from Mike McCready‘s Clapton/Hendrix-style leads — every trace of blues influence has been completely stripped from the band’s sound. Though they rock hard, Pearl Jam is too anti-star to swagger, too self-aware to puncture the album’s air of gravity. Pearl Jam tackles weighty topics — abortion, homelessness, childhood traumas, gun violence, rigorous introspection — with an earnest zeal unmatched since mid-’80s U2, whose anthemic sound they frequently strive for. Similarly, Eddie Vedder‘s impressionistic lyrics often make their greatest impact through the passionate commitment of his delivery rather than concrete meaning. His voice had a highly distinctive timbre that perfectly fit the album’s warm, rich sound, and that’s part of the key — no matter how cathartic Ten‘s tersely titled songs got, they were never abrasive enough to affect the album’s accessibility. Ten also benefited from a long gestation period, during which the band honed the material into this tightly focused form; the result is a flawlessly crafted hard rock masterpiece.

1993 BJORK – DEBUT

Freed from the Sugarcubes‘ confines, Björk takes her voice and creativity to new heights on Debut, her first work after the group’s breakup. With producer Nellee Hooper‘s help, she moves in an elegantly playful, dance-inspired direction, crafting highly individual, emotional electronic pop songs like the shivery, idealistic “One Day” and the bittersweet “Violently Happy.” Despite the album’s swift stylistic shifts, each of Debut‘s tracks are distinctively Björk. “Human Behaviour”‘s dramatic percussion provides a perfect showcase for her wide-ranging voice; “Aeroplane” casts her as a yearning lover against a lush, exotica-inspired backdrop; and the spare, poignant “Anchor Song” uses just her voice and a brass section to capture the loneliness of the sea. Though Debut is just as arty as anything she recorded with the Sugarcubes, the album’s club-oriented tracks provide an exciting contrast to the rest of the album’s delicate atmosphere. Björk‘s playful energy ignites the dance-pop-like “Big Time Sensuality” and turns the genre on its head with “There’s More to Life Than This.” Recorded live at the Milk Bar Toilets, it captures the dancefloor’s sweaty, claustrophobic groove, but her impish voice gives it an almost alien feel. But the album’s romantic moments may be its most striking; “Venus as a Boy” fairly swoons with twinkly vibes and lush strings, and Björk‘s vocals and lyrics — “His wicked sense of humor/Suggests exciting sex” — are sweet and just the slightest bit naughty. With harpist Corky Hale, she completely reinvents “Like Someone in Love,” making it one of her own ballads. Possibly her prettiest work, Björk‘s horizons expanded on her other releases, but the album still sounds fresh, which is even more impressive considering electronic music’s whiplash-speed innovations. Debut not only announced Björk‘s remarkable talent; it suggested she had even more to offer.

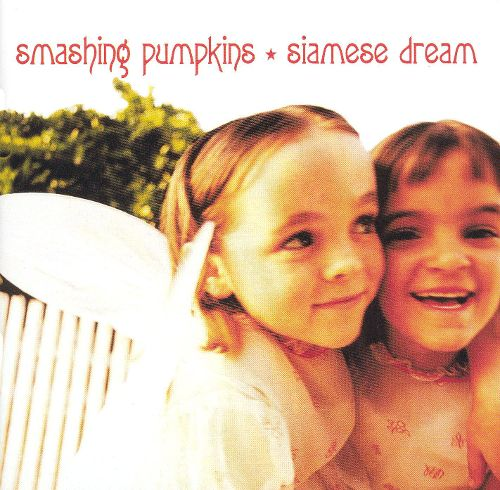

1993 SMASHING PUMPKINS – SIAMESE DREAM

While Gish had placed the Smashing Pumpkins on the “most promising artist” list for many, troubles were threatening to break the band apart. Singer/guitarist/leader Billy Corgan was battling a severe case of writer’s block and was in a deep state of depression brought on by a relationship in turmoil; drummer Jimmy Chamberlin was addicted to hard drugs; and bassist D’Arcy and guitarist James Iha severed their romantic relationship. The sessions for their sophomore effort, Siamese Dream, were wrought with friction — Corgan eventually played almost all the instruments himself (except for percussion). Some say strife and tension produces the best music, and it certainly helped make Siamese Dream one of the finest alt-rock albums of all time. Instead of following Nirvana‘s punk rock route, Siamese Dream went in the opposite direction — guitar solos galore, layered walls of sound courtesy of the album’s producers (Butch Vig and Corgan), extended compositions that bordered on prog rock, plus often reflective and heartfelt lyrics. The four tracks that were selected as singles became alternative radio standards — the anthems “Cherub Rock,” “Today,” and “Rocket,” plus the symphonic ballad “Disarm” — but as a whole, Siamese Dream proved to be an incredibly consistent album. Such compositions as the red-hot rockers “Quiet” and “Geek U.S.A.” were standouts, as were the epics “Hummer,” “Soma,” and “Silverfuck,” plus the soothing sounds of “Mayonaise,” “Spaceboy,” and “Luna.” After the difficult recording sessions, Corgan stated publicly that if Siamese Dream didn’t achieve breakthrough success, he would end the band. He didn’t have to worry for long — the album debuted in the Billboard Top Ten and sold more than four million copies in three years. Siamese Dream stands alongside Nevermind and Superunknown as one of the decade’s finest (and most influential) rock albums.

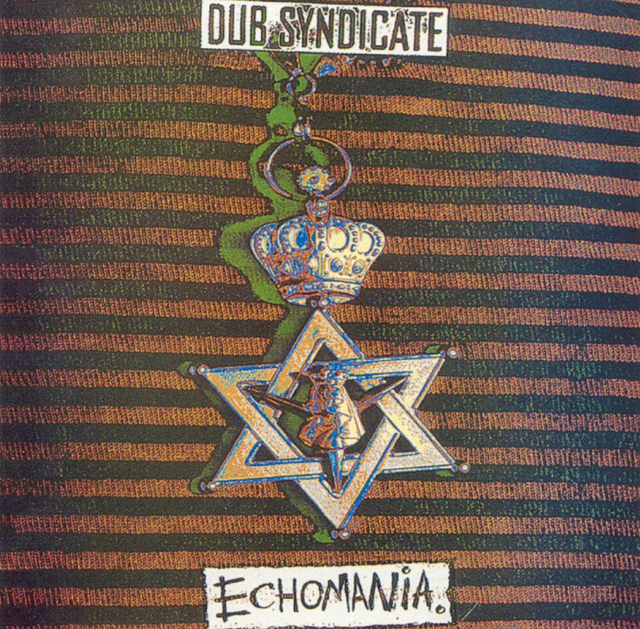

1994 Dub Syndicate - Echomania

This disc finds Dub Syndicate back to full strength. Thanks to an all-too-brief distribution arrangement with Restless Records in the U.S., this is one On-U title that should be relatively easy to find in the States, and it will make a fine introduction for newcomers to the band's strange but wonderful art. Drummer "Style" Scott and bassist "Flabba" Holt keep everyone together with monstrous reggae riddims, while Adrian Sherwood tears things up around them from his perch at the mixing board. Lee "Scratch" Perry makes a couple of hilarious cameo appearances, in one case sentencing all "heads of government" to "poverty and famine and hardship and bad luck." When guitarist Skip McDonald sings, you can hear echoes of his past work with Tackhead and intimations of what will come with Strange Parcels. Everywhere the rhythms are airtight and relentlessly propulsive. One song manages to quote successfully the American gospel standard "Walking in Jerusalem Just Like John." A rare and wonderful recording.

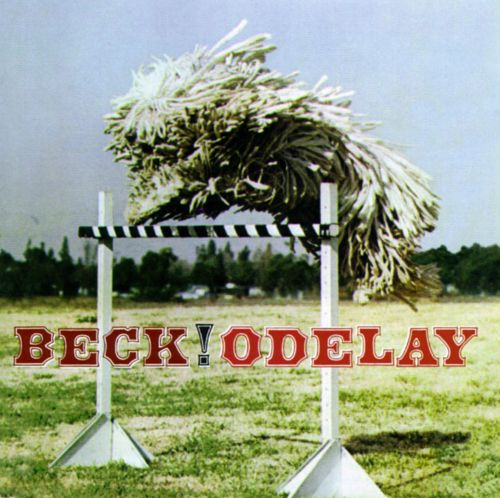

1996 BECK – ODELAY

Unlike Stereopathetic Soul Manure and One Foot in the Grave, the indie albums that followed his debut Mellow Gold by a mere matter of months, Odelay was a full-fledged, full-bodied album, released on a major label in the summer of 1996 and bearing an intricate, meticulous production by the Dust Brothers in their first gig since the Beastie Boys‘ Paul’s Boutique. Odelay shared a similar collage structure to that 1989 masterpiece, relying on a blend of found sounds and samples, but instead of lending the album its primary colors, the Dust Brothers provided the accents, highlighting Beck‘s ever-changing sounds, tying together his stylistic shifts, making the leaps from the dirge-blues of “Jack-Ass” to the hazy party rock of “Where’s It’s At” seem not so great. Like Mellow Gold, Odelay winds up touching on a number of disparate strands — folk and country, grungy garage rock, stiff-boned electro, louche exotica, old-school rap, touches of noise rock — but there’s no break-neck snap between sensibilities, everything flows smoothly, the dense sounds suggesting that the songs are a bit more complicated than they actually are. Most of the songs here betray Beck‘s roots as an anti-folk singer — he reworks blues structures (“Devil’s Haircut”), country (“Lord Only Knows,” “Sissyneck”), soul (“Hotwax”), folk (“Ramshackle”) and rap (“High 5 [Rock the Catskills],” “Where It’s At”) — but each track twists conventions, either in their construction or presentation, giving this a vibrant, electric pulse, surprising in its form and attack. Like a mosaic, all the details add up to a picture greater than its parts, so while some of Beck‘s best songs are here, Odelay is best appreciated as a recorded whole, with each layered sample enhancing the allusion that came before.

1997 PRODIGY – THE FAT OF THE LAND

Few albums were as eagerly anticipated as The Fat of the Land, the Prodigy‘s long-awaited follow-up to Music for the Jilted Generation. By the time of its release, the group had two number one British singles with “Firestarter” and “Breathe” and had begun to make inroads in America. The Fat of the Land was touted as the album that would bring electronica/techno to a worldwide audience (Of course, in Britain, the group already had a staggeringly large following that was breathlessly awaiting the album.) The Fat of the Land falls short of masterpiece status, but that isn’t because it doesn’t deliver. Instead, it delivers exactly what anyone would expect: intense hip-hop-derived rhythms, imaginatively reconstructed samples, and meaningless shouted lyrics from Keith Flint and Maxim. Half of the album does sound quite similar to “Firestarter,” especially when Flint is singing. Granted, Liam Howlett is an inventive producer, and he can make empty songs like “Smack My Bitch Up” and “Serial Thrilla” kick with a visceral power, but he is at his best on the funky hip-hop of “Diesel Power” (which is driven by an excellent Kool Keith rap) and “Funky Shit,” as well as the mind-bending neo-psychedelia of “Narayan” (featuring guest vocals by Crispian Mills of Kula Shaker) and the blood-curdling cover of L7‘s “Fuel My Fire,” which features vocals by Republica‘s Saffron. All those guest vocalists mean something — Howlett is at his best when he’s writing for himself or others, not his group’s own vocalists. “Firestarter” and all of its rewrites capture the fire of the Prodigy at their peak, and the remaining songs have imagination that give the album weight. The Fat of the Land doesn’t have quite enough depth or variety to qualify as a flat-out masterpiece, but what it does have to offer is damn good.

2003 THE WHITE STRIPES – ELEPHANT

White Blood Cells may have been a reaction to the amount of fame the White Stripes had received up to the point of its release, but, paradoxically, it made full-fledged rock stars out of Jack and Meg White and sold over half a million copies in the process. Despite the White Stripes‘ ambivalence, fame nevertheless seems to suit them: They just become more accomplished as the attention paid to them increases. Elephant captures this contradiction within the Stripes and their music; it’s the first album they’ve recorded for a major label, and it sounds even more pissed-off, paranoid, and stunning than its predecessor. Darker and more difficult than White Blood Cells, the album offers nothing as immediately crowd-pleasing or sweet as “Fell in Love With a Girl” or “We’re Going to Be Friends,” but it’s more consistent, exploring disillusionment and rejection with razor-sharp focus. Chip-on-the-shoulder anthems like the breathtaking opener, “Seven Nation Army,” which is driven by Meg White‘s explosively minimal drumming, and “The Hardest Button to Button,” in which Jack White snarls “Now we’re a family!” — one of the best oblique threats since Black Francis sneered “It’s educational!” all those years ago — deliver some of the fiercest blues-punk of the White Stripes‘ career. “There’s No Home for You Here” sets a girl’s walking papers to a melody reminiscent of “Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground” (though the result is more sequel than rehash), driving the point home with a wall of layered, Queen-ly harmonies and piercing guitars, while the inspired version of “I Just Don’t Know What to Do With Myself” goes from plaintive to angry in just over a minute, though the charging guitars at the end sound perversely triumphant. At its bruised heart, Elephant portrays love as a power struggle, with chivalry and innocence usually losing out to the power of seduction. “I Want to Be the Boy” tries, unsuccessfully, to charm a girl’s mother; “You’ve Got Her in Your Pocket,” a deceptively gentle ballad, reveals the darker side of the Stripes‘ vulnerability, blurring the line between caring for someone and owning them with some fittingly fluid songwriting.

The battle for control reaches a fever pitch on the “Fell in Love With a Girl”-esque “Hypnotize,” which suggests some slightly underhanded ways of winning a girl over before settling for just holding her hand, and on the show-stopping “Ball and Biscuit,” seven flat-out seductive minutes of preening, boasting, and amazing guitar prowess that ranks as one the band’s most traditionally bluesy (not to mention sexy) songs. Interestingly, Meg‘s star turn, “In the Cold, Cold Night,” is the closest Elephant comes to a truce in this struggle, her kitten-ish voice balancing the song’s slinky words and music. While the album is often dark, it’s never despairing; moments of wry humor pop up throughout, particularly toward the end. “Little Acorns” begins with a sound clip of Detroit newscaster Mort Crim’s Second Thoughts radio show, adding an authentic, if unusual, Motor City feel. It also suggests that Jack White is one of the few vocalists who could make a lyric like “Be like the squirrel” sound cool and even inspiring. Likewise, the showy “Girl, You Have No Faith in Medicine” — on which White resembles a garage rock snake-oil salesman — is probably the only song featuring the word “acetaminophen” in its chorus. “It’s True That We Love One Another,” which features vocals from Holly Golightly as well as Meg White, continues the Stripes‘ tradition of closing their albums on a lighthearted note. Almost as much fun to analyze as it is to listen to, Elephant overflows with quality — it’s full of tight songwriting, sharp, witty lyrics, and judiciously used basses and tumbling keyboard melodies that enhance the band’s powerful simplicity (and the excellent “The Air Near My Fingers” features all of these). Crucially, the White Stripes know the difference between fame and success; while they may not be entirely comfortable with their fame, they’ve succeeded at mixing blues, punk, and garage rock in an electrifying and unique way ever since they were strictly a Detroit phenomenon. On these terms, Elephant is a phenomenal success.

three jerks make a masterpiece

the beastie boys (ya know one of was a jew)

I always thought all three Beasties were jews.

Most of those albums have at least one jew in a key role - if not in the band, at least the manager or record company owner.

Even the frigging Clash!

"Today would be Joe Strummer’s 57 birthday. Born John Graham Mellor, he was one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, mostly for his work as frontman of the Clash. He died suddenly in 2002 of an undiagnosed heart defect. He was also part Jewish.

Strummer formed the Clash in 1976, the same year the Ramones broke out and the Sex Pistols began their short-lived run. In 1977 the Clash released their first album, a classic that blended punk with reggae - a sound that countless bands would imitate but never master like the Clash. Their 1979 record “London Calling” is one of the most critically acclaimed rock albums of all time and opened the possibilities of punk music to more than three-chord, three-minute songs. By the time the Clash disbanded in the mid 1980s, they had put out six studio albums (including the double album “London Calling” and the triple album “Sandinista”)"

I stand corrected

You got a 3.01% upvote from @upme thanks to @frot! Send at least 3 SBD or 3 STEEM to get upvote for next round. Delegate STEEM POWER and start earning 100% daily payouts ( no commission ).

Next I'll see if all this evilness pays off...

You got a 2.64% upvote from @postpromoter courtesy of @frot!

Want to promote your posts too? Check out the Steem Bot Tracker website for more info. If you would like to support the development of @postpromoter and the bot tracker please vote for @yabapmatt for witness!