[FILM ESSAY] Nostalghia (1983) by Andrei Tarkovsky

How many movies are there, where each frame in itself is a work of art? Every scene, every shot so meticulously planned to perfection, every detail so carefully executed. The long takes. The slow and meditative pace. There is not an ounce of compromise in a single image. Verdi's requiem in the phenomenal final scenes still echoes long after the film has ended. And Nostalghia is ultimately a requiem of an irreversible time that once were, but never again will be. All that remains is a ruin.

I regard every film of Tarkovsky as a small island, or a sanctuary. You visit them not to experience an outer journey, but rather an internal. This film is no exception. It took me on a profoundly deep and spiritual journey, away from the society and modernity that Domenico, the Holy fool in the film, questions in a blazing and self-sacrificing speech on the statue. The careful and poetic imagery is in itself a rebellion against all the pragmatic rush to quickly get to a narrative structure and content in mainstream cinema.

This film, which was Tarkovsky's first since the exile from the Soviet Union, is a melancholic and poetic piece, partly about the pain of exile and the wonders of life. A Russian professor, a young female interpreter and a hermit (Domenico) obsessed with the idea of saving mankind, are the protagonists of the story.

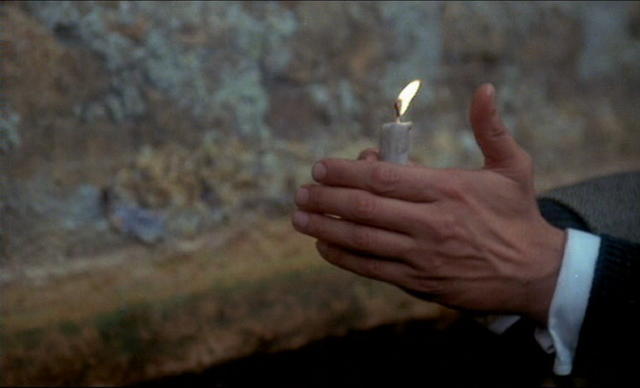

It may sound difficult and inaccessible. But Tarkovsky's images are wide open to interpretation. There's no firm dramaturgy behind the scenes in which Domenico time after time wanders through the empty pool in the small village among the Italian mountains with a flickering candle in his hand. A seemingly strange and incomprehensible ritual.

"Remember the candles in Orthodox churches, how they flicker. The very essence of things, the spirit, the spirit of fire" - Andrei Tarkovsky

In the beginning of Andrei Tarkovsky's Nostalghia we find ourselves in a ruined monastery in the Tuscan hills. A procession with a giant image of the Madonna slowly approaches in the dark crypt. One of the praying women opens the skirt of the Madonna. From the creases a flock of pigeons fly out with a clattering sound. The scene sets the symbolic resonance of this whole remarkable film.

Nostalgia means homesickness. According to Tarkovsky it's a disease. Far more than just a feeling of sadness, it's a force that robs us of zeal and courage. Nostalgia is the lack of human community in a spiritual sense, the loss of faith and hope. The exile of the soul.

Two important themes converge in Nostalghia: on the one hand Tarkovsky's deep pessimism that highlights our imprisonment in language, history and environment. On the other hand a universal rootlessness, a disease of civilization true far beyond an actual nostalgia. The ties to the whole, the umbilical to Mother Earth, is cut off.

Nostalghia, set in Italy, portrays a Russian intellectual, Gorchakov, in voluntary exile. He's searching for traces of his fellow countryman, Saznovsky, an exiled Russian composer. But we never actually see Gorchakov being engaged in the search for him. Gorchakov is rather searching for something that people are looking for in so many other of Tarkovsky's films, namely identity and domicile in the internal sense, a dilemma that is driven to a dramatic climax in the collision between the Russian and Western European. When we first meet Gorchakov he's in a "zero position". He's having difficulties mapping out the boundaries of his own self, and is searching for something that isn't apparent, and therefore he can't know whether, what or when he will find, only that it's something that he's lacking.

Tormented by the longing for his wife and children, his homesickness is killing him. The german word Elend means both misery and exile, and would be a fitting word to describe the state of Gorchakov. He's thirsting for the motherland, for the Russian soil, for the woman, for the mother, for god. He's literally beside himself - locked out of himself, his inner source. Tarkovsky paints his inner parched landscape in a gloomy gray scale.

Nostalghia is dominated by a disaster perspective. The downfall looms over humanity. From the Marcus Aurelius statue in Rome Domenico preaches, like the antique Cassandra, of a new human community around the simplicity of life: eating, talking and sleeping together. He set himself on fire to get the world to see their own folly, while shouting for collective action to save a civilization in collapse. A romantic fool's futile attempt to reverse the march towards the abyss? Or maybe he's the only one that is not a fool?

Tarkovsky was in many ways a cultural conservative: he was upholding religious tradition, he turned away from contemporary political life and he was an ardent exponent for his national and cultural identity. But he was a low-key traditionalist. That is, he had no political profile to speak of. His films were never about politics per se and his films were far from bombastic or chauvinistic, but he was always an avid spokesperson, sometimes fanatical, for Russian culture and its distinctiveness. When Nostalghia came in the 80s, he said that Russians and Western Europeans probably can study and enjoy each others art and literature, but never reach true and profound understanding of what the pieces are about. A Russian can't fully understand Dante, in the same way that an Italian can't fully understand Dostoevsky. A Russian can't have an in depth experience of Petrarca, in the same way an Italian can't have an in depth experience of Pushkin, and so on.

I'm not sure I entirely agree with this. To be strongly rooted in one's own culture is not necessarily an obstacle to appreciating other cultures. Tarkovsky's films, so much molded in Russian distinctiveness, has received the marvel and awe from nearly all cinephile's in the Western world; rather making his films arguments for the universal and for art's ability to unite.

The film is about being a Russians in exile, just like Tarkovsky. But it's about so much more than that. When Gorchakov breaks up with his Italian interpreter and girlfriend, Eugenia, he occupies himself with spiritual matters. It's all expressed symbolically. Gorchakov makes Domenico a promise to wade through a pool with a burning candle. It's quite enigmatic, and as a gesture considered quite modest, but I don't have a problem with accepting this. A gesture is always modest in itself. Just a symbolic act? Of course. But the symbols and myths uncover important connections, penetrates backwards, inwards. To light a candle, what does it mean? Gorchakov's slow walk with the candle through the pool, doing his best to keep the flame alive, represents a journey from the periphery to the center. A homecoming. Tarkovsky is on to something here. The symbolic language is convincing.

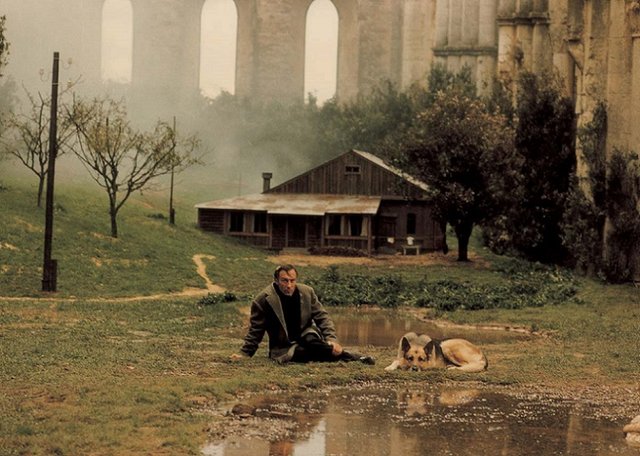

Gorchakov carries the light over the drained pool. When he reaches the other side, he manages to place the light on a niche, as he suffers a heart attack. It's only hinted, but you understand precisely. Gorchakov has sacrificed himself - for spirituality, the arts, for the reconciliation between East and West, whatever you want. The film ends with an inscrutable, striking image: Gorchakov sits in front of his Russian home, a house that we throughout the film have seen glimpses of in parallel scenes, a symbol of Russia, from where he is exiled.

There he sits, in front of his Russian house, with a dreamlike background constituted by a wall of an Italian church ruin. Then the camera zooms out and you can also see the side walls of the ruin, which is now enclosing the whole scenery. This whole vision of the house framed by the church ruin is an image that can be interpreted in many different ways. One way is to see it as the reconciliation and understanding, a synthesis between East and West - in the guise of a man surrounded by a striking mix of architecture, Russian and Italian.

Gorchakov in front of his house, with the church ruin walls as a giant backdrop: this is spirituality on the screen, this is Tarkovsky in a nutshell. It's spirituality without any form of apology or irony. Tarkovsky was deeply rooted in his faith in God and he managed to convey that. The tone of Nostalghia is sometimes a bit pessimistic, I admit. Even the spirituality in this context is a bit dull. However, some form of ambiguity is retained. The sadness and somberness can be interpreted as pathos, or humility.

A key character is the self-sacrificing hermit Domenico, a symbol of spirituality and resistance towards modernity. He's what you could call a Holy fool, a village idiot and prophetic "madman" to most, who sacrifices himself on the altar of human unity. And Holy folly has a prominent role in Orthodox religion, and has always been a well used subject for Russian artists and poets. In the eyes of the interpreter Eugenia, Domenico is only worthy of contempt, he's a nothing but a madman. Gorchakov in contrast immediately understands that Domenico is a deeply profound and humble person, unlike the others around him. And humbleness is another subject of great importance in Tarkovsky's philosophy. Faith requires a basic humility for the great and unspeakable that allows the individual to break out of introversion and grow beyond his or her personal limitations.

In Tarkovsky's films, the focus is not only people; places, houses and rooms are often central characters. In a scene in Nostalghia, Gorchakov walks around in a church ruin. It's the ruin of an unremarkable Roman church. The floor is covered with water. Water in various forms (puddles, rain, half-submerged structures and objects, water running down the walls etc.) are recurring metaphors in Tarkovsky's movies. Here Gorchakov wades around in his ruin, with water up to his calves. It's an image of sublime beauty that must be seen to be appreciated. As he's walking through the ruin he's drinking vodka and smoking and preaching about the wretchedness of the West, its materialism and superficiality. As for the message itself, you need not see it as Russian criticism of the West specifically. A lot of western cultural conservatives, not least Roger Scruton, address the same points.

In a stunning scene Gorchakov enters a deserted house in Italy. He goes upstairs to an attic with a window. On the floor there's a model of a Russian mountainous landscape. It's obvious that it's a model, but as a viewer you accept the idea (a model landscape built directly on the floor in an attic) due to the meditative narration. The camera slowly moves towards the landscape until it's the only thing that is visible. A shift in perspective occurs. The model landscape captures you attention and pulls you into it, towards its rivers, its mountains and its backdrop of a sky. I know no other filmmaker that can achieve such effects with as simple, yet at the same time ingenious maneuvers.

- SteemSwede

Thanks for sharing

@steemswede

I like your post

It seems like you had a connection with this film. Thanks for sharing

Brilliantly written and got me interested well done :)

Thank you, glad I got you interested!