Galway Bay Marathon 2021

After completing the Carlingford Half Marathon on 7 March 2020, I returned home to prepare for my next race. I was planning to run two marathons in 2020: the Brighton Marathon on 19 April, and the Galway Bay Marathon on 3 October. Needless to remark, both events were postponed due to the covid-19 pandemic. The Brighton Marathon was eventually rescheduled for 12 September 2021, and the Galway Bay Marathon for 2 October. I could not run both of them, so I opted for the latter.

This was my second ketogenic marathon. I ran my first on 5 May 2019: the Limerick Great Run. For my previous twenty-three marathons, I had followed the traditional runner’s diet—the glycogenic diet—which is high in carbohydrates and low in fat (HCLF). The ketogenic diet is low in carbs and high in fat (LCHF). Because fat provides a significant percentage of the ketogenic runner’s fuel, glycogen is spared and carbo-loading is not required before a marathon. When I ran the Limerick Marathon, I had only been following this new diet for five months. Understandably, I did not want to take any chances, so I ran with the three-hour pacemakers. In the end, I needn’t have worried. I had little difficulty sustaining a three-hour pace and even finished with a spurt, for a time of 2:58:18.

At the time, I suspected that after only five months, I was probably still drawing upon training I had done while still a glycogenic runner. I was hoping to really test the concept of running fast marathons on the ketogenic diet in 2020, with more than a year of ketogenic training under my belt. Covid put paid to this plan, but perhaps that was a good thing, as the transition from glycogenic to ketogenic marathon running was long and difficult.

Adapting to Keto

I had been warned by other runners who had gone down this route before me to expect a significant drop in performance. And this is exactly what I experienced. My pace dropped, my endurance declined, and the strength of my legs decreased. Initially, the last of these was the most noticeable. All the strength seemed to have been drained out of my legs. Whenever I went out for a run, I felt heavy-legged and sluggish—similar to how you feel when “the bear jumps on your back”. And this sensation was not confined to running. Walking and cycling took much more out of me than ever before. Even climbing the stairs at home could leave me a little breathless. In short, the bounce-out-of-bed energy levels that I had enjoyed in the past were gone.

This led to a drop-off in my pace. In the past I could always hit the road running, and set off on a run at a fast pace. But now it seemed to take ten or fifteen minutes just to get the engine warmed up. Running was becoming harder, and more of a chore than a pleasure. I also slowed down when walking or cycling. The energy just wasn’t there to sustain a fast pace.

The decline in my endurance took longer to kick in, but it finally caught up with me. When I made the switch to the ketogenic diet, I was running about eight hours a week, including a three-hour long run. Initially, I continued to follow this regimen, albeit at a slower pace, but after a few months I was finding it difficult to complete my weekly mileage. One Sunday, when I was about an hour into my long run, I had to turn for home and curtail the run to just two hours. This was the first time in twenty-five years of marathon running that I had had to cut a long run short due to exhaustion. Had I finally “hit the wall”?

I felt I had no other option but to revise my training schedule for the Limerick Marathon. I decided to reduce everything by a third. In the final few months, I restricted my weekly mileage to just six hours and my long runs to two hours. My speed work was also reduced in intensity. This new schedule, with more realistic targets, saw me through my first keto marathon in Limerick (5 May 2019) and my first keto half-marathon (Clonakilty 30 November 2019).

Patience is a great thing, and I did not panic. Despite these drawbacks, the ketogenic lifestyle was too healthy to abandon. And it did come with one great advantage for a distance runner: chronic inflammation seemed to be a thing of the past. Tough sessions and races had always left me tired, and that did not change, but I no longer experienced the aches and pains that I had come to accept as a necessary part of the marathon runner’s life. So I persevered.

And perseverance finally seems to be paying off. The turning point occurred around June-July 2021, thirty or so months after I had adopted the ketogenic diet. Without warning, I just noticed that the spring was coming back into my legs. I was walking and cycling at my old pace again. I could run up the stairs at home like a young buck. I could set out on a run at a brisk pace without having to warm up, and I wasn’t running out of steam after only two hours.

My training schedule for 2020—prepared before the pandemic in the belief that I would be running Brighton in April and Galway in October—included long runs of 2:20, a weekly mileage of six hours, and a rest day on Sundays. But the revised schedule that I actually followed a year later for Galway included long runs of 2:30 to 2:50, a weekly mileage of 7:00-7:20 hours, and no rest days. I still couldn’t do any speed work on the treadmill in the gym, which was closed, but that was the only thing missing from my usual schedule.

The Big Day

When I set off for Galway, I brought with me a packed ketogenic dinner to eat in my hotel room the evening before the race. Dinner consisted of a corned-beef sandwich (made with keto microwave bread, of course—almond flour, flax seeds, butter, eggs, salt, baking powder and xanthan gum) and a few “pastries” made with fat-head dough (mozzarella cheese, egg, almond flour, salt, baking powder and xanthan gum). This is more-or-less what I ate before the Limerick Marathon and the Carlingford Half-Marathon.

On the morning of the race, I drank 500 ml of still water in which I had dissolved one serving (14 g) of Dr Boz’s Exogenous Ketones (Raspberry-Lemonade Flavour), and 4 g of Bulk’s Electrolyte Powder.

When I left my hotel for the start of the race, I carried with me another 500 ml bottle filled with the same dose. Those 500 ml kept me hydrated for about half the race. When I ran out, I switched to the small 250 ml bottles of still water provided by the race stewards.

The conditions were far from ideal. There was a very strong westerly wind blowing—26 kph with gusts up to 35 kph. It was not cold—12° C—and although there was drizzle when we started, the rain soon stopped and the sun came out.

The course comprised six laps: two short laps for the first 7 or 8 km, followed by four long laps of 8-9 km each. The short lap was very flat. There was, however, one difficult hill in the long lap. The change of elevation along this hill was only about eight metres (from 0 m to 8 m above sea-level), but this was compressed into a distance of only 400 m, which we had to climb in the teeth of the stiff breeze. Without that wind, I would not even have noticed such a hill. But in these conditions, it knocked the stuffing out of me every time I encountered it. You can see this hill on the course profile at approximately 8 km, 17 km, 26 km, and 35 km. (Note: this profile was created for the 2015 Galway Bay Marathon, which followed a slightly different route than the 2021 race.)

The race started and finished on Nimmo’s Pier, in the Claddagh. This was about 1.5 km from my hotel on Eyre Square (Imperial Hotel). There were about 900 starters for the full Marathon, with almost 1500 runners taking part in the two shorter disciplines (Half Marathon and 10K).

The first lap was slightly longer than the second. Most runners ran the first lap one to two minutes slower than the second. Mercifully, both were completely flat, so we only had the wind to contend with. Nevertheless, I set out at a fairly respectable pace, completing the two opening laps in about 16 and 15 minutes respectively.

The halfway point was not marked, but according to my Garmin Forerunner GPS Watch, I passed through 21.1 km in just under 90 minutes, so I was bang on three-hour pace. And I was still on course for a three-hour finish at 28 km, or two-thirds of the way through. It was then that my pace began to fall away. I really struggled to get up the hill the third and fourth times, and needed time to recover on the downslope, whereas on the first two laps, most of the time I lost on the upslope I regained on the downslope.

My finishing time of 3:04:12 was the slowest I have ever run and the first time in twenty-five marathons that I have failed to break the three-hour mark:

| Marathon | Year | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Budapest | 2015 | 2:41:05 |

| Cork | 2017 | 2:57:50 |

| Pisa | 2017 | 2:44:55 |

| Limerick | 2019 | 2:58:19 |

| Galway | 2021 | 3:04:12 |

Despite the time, however, I finished 15th overall, 1st in the M50 category, and about seventeen minutes ahead of the winner of the women’s race. Only the top ten finishers broke the three-hour barrier, and the winning time—2:36:23—is one that I have bettered on three occasions and equalled in the 2010 Dublin Marathon. So, clearly, I was not the only runner who had difficulty coping with the windy conditions.

Postmortem

This was the slowest of my twenty-five marathons, and the first time I have ever failed to break the three-hour mark. What was the reason for this? I can think of three factors, each of which probably contributed something to my overall time:

Conditions I hate running marathons in windy conditions. In Galway, there was a very strong and persistent wind of 26 kph with gusts up to 35 kph. The course was flat for the most part, but there was that short but sharp hill which we had to negotiate four times, each time in the teeth of the strong wind. I do not know whether these difficult conditions added more or less than five minutes to my overall time, but they certainly cost me some time. In such conditions it is impossible to maintain a steady pace. One minute you are being blowing along by a strong tailwind, the next you are battling against a gale. That is one sure-fire way to tire yourself out in a marathon.

Age I was 57 years and 7 months old when I ran the Galway Bay Marathon. I cannot expect to keep running sub-three-hour marathons indefinitely. Every time I run a marathon, I am several months older than I was when I ran my last one—several months further over the hill. This has to be a relevant factor. Because of covid, I ran Galway two years and five months after my previous marathon. I cannot escape the fact that in my case, age will always be a confounding factor when it comes to assessing how well I am adapting to the ketogenic regimen.

Keto I may also have to accept that keto and competitive marathon running do not go together, but I am not prepared to accept this conclusion yet. Although the transition from glycogenic running has been very difficult for me, and involved a pronounced drop-off in my performance, my body does seem to be finally adapting to this new way of running. It took thirty months to turn the corner, so perhaps I just need to be patient and stick at it.

It is clear from my official splits that I was holding things together for about two-thirds of the race. It was the last two laps that let me down. I ran the first two long laps in 74:28, and the last two in 78:51. There’s your four minutes and twelve seconds right there!

| Position | Name | Category | Short 1 | Short 2 | Lap 1 | Lap 2 | Lap 3 | Lap 4 | Final Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | Brendan Ward | Over 50 Male | 0:15:59 | 0:14:51 | 0:36:51 | 0:37:37 | 0:39:18 | 0:39:33 | 3:04:12 |

Hopefully, my next marathon will go some way to answering these questions.

After the Race

Galway is a small city situated on Ireland’s Atlantic coast. It is one of Ireland’s better known cities and is steeped in history. After the race, when I had showered and changed, I went to Caffè Nero on Eyre Square and had a cappuccino and a croissant—not remotely keto, but after a marathon, all bets are off.

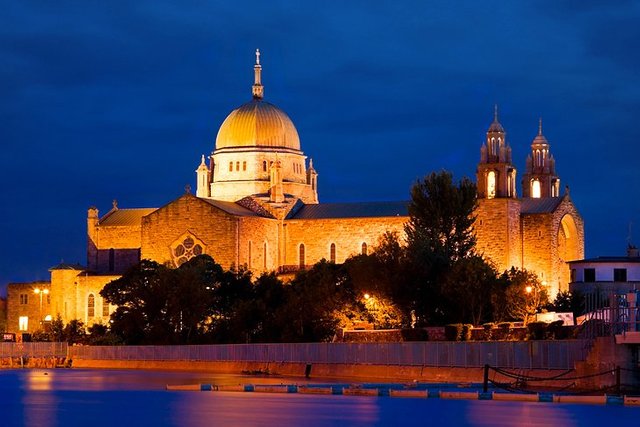

One of Galway’s most striking buildings is the Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St Nicholas:

The city sits on the River Corrib. At 6 km long, this is one of Ireland’s shortest rivers, but it drains one of the country’s largest lakes—Lough Corrib, which is second in area only to Lough Neagh. The Corrib’s mean flow rate of over 100 cubic metres per second is surpassed only by that of the Shannon:

Galway is home to the National University of Ireland, which has graced the banks of the Corrib for over 170 years:

And Finally

A big thank-you to the organizers of Run Galway Bay for making this year’s marathon happen at a time when it would have been easy to postpone it for another twelve months.

Image Credits

- Galway Bay Marathon: © Google Maps, Fair Use

- Going Keto: © Carmichael Training Systems, Fair Use

- Hitting the Wall: © Getty Images, Fair Use

- Galway Bay Marathon Profile: Profile for 2015 Marathon, Map My Run, Mirko Wamke (creator), Fair Use

- Keto Dietitian Lotte Damen in the Valencia Marathon 2019: © Lotte Damen, Fair Use

- Dr Boz’s Exogenous Ketones: © 2021 BozMD.com, Fair Use

- Bulk Electrolyte Powder: © BulkTM, Fair Use

- Marathon Start on Nimmo’s Pier: © Run Galway Bay, Fair Use

- Andrew O’Neill, Winner of the Galway Bay Marathon 2021: © Run Galway Bay, Fair Use

- Caffè Nero, Eyre Square: © 2021 Restaurant Guru, Fair Use

- Galway Cathedral: © Getty Images, Fair Use

- River Corrib from Wolfe Tone Bridge: © James Byard, Fair Use

- NUI Galway: © 2021 National University of Ireland, Galway, Fair Use

- Galway’s Latin Quarter: © Carlos Echeveste (photographer), Shutterstock, Fair Use