Book Review -- Strength in What Remains by Tracy Kidder

—Tracy Kidder, Strength in what Remains She said she'd never heard of a country called Burundi.

"Are you sure it isn't Burma?" she asked him.

Before 1994, few people in the United States had heard of Rwanda. Today, the name remains a placeholder for some of the most deplorable acts of ethnic violence committed in the twentieth century. Genocide, however, was not just unique to Rwanda—mass killing and civil war shaped by the same ethnic distinctions of Hutu and Tutsi also took place in the neighboring country Burundi.

With Strength in What Remains, Pulitzer Prize winning author Tracy Kidder presents the story of Deogratias: a former third year medical student and Burundian refugee who escaped the country’s civil war in 1994. Told through a limited third person point-of-view up until Deo’s return to Burundi in 2006, Kidder effectively presents the reader with a story that goes beyond the horrors of genocide. Instead, we learn about the life Deogratias—a Burundian, a U.S. citizen, a survivor, and a man who, despite the atrocities committed against him and his family, eventually returns to his homeland to help the people.

In order to go on with our lives, we are always capable of making the ominous into the merely strange.

But the book is not just another story of overcoming adversity; it presents a number of issues. Kidder’s writing style gives the reader a front-row view of our own prejudices, including what life is like in third world countries, the importance of education, and the detrimental effects of poverty. By allowing the readers to compare their own emotional reactions with those of Kidder, Strength delivers a story capable of reshaping the mainstream public’s perception of what it means to be a survivor of genocide, a citizen of a poor country, and a human being struggling to find meaning in it all.

Separated into two parts-- Flights and Gusimbura—the first section of the book recounts Deo’s experiences growing up in a poor African country, of civil war, and his narrow escape to New York City. The second section, Gusimbura, chronicles Deo and Kidder’s trip to Burundi after the civil war. The term gusimbura, which appears in the introduction of the book, expresses the Burundian desire not to remember tragedies but to forget them.

He sniffed, and said as others had before him and others no doubt would again, "I have learned never to say, 'Never again.'"

The chapters are not structured chronologically. Instead, the story of Deo’s escape—the last of his many flights—begins, as luck would have it, on an airplane prepared to takeoff from Burundi in May 1994. The chapter’s narrative style, not unlike how one might expect the script of the Blair Witch Project to read, allows the reader’s mind to race alongside Deo’s. Short successions of Deo’s frantic thoughts are separated by detailed descriptions of the airplane and the landscape outside; the reader knows he survived but nothing more. Deo lands in New York with $200, no place to go, and no command of the English language. Luckily, he meets a Senegalese immigrant working at the airport who invites him to stay in an abandoned building. Never divulging many details at once, Kidder slowly builds the story of Deo’s past by alternating between the life he was creating in the United States and the one he had in Burundi prior to the civil war.

Kidder’s description of the social and economic circumstances in which Deo was raised will likely defy most of the Western world’s perception of what life would be like living in post-colonial Africa where land was the only natural resource and a family’s societal rank was determined by the number of cows they owned. The story of Deo’s life in Burundi begins in the 1970s. Set nearly twenty five years before the outbreak of violence in 1993, it quickly becomes evident that Burundi was not a stranger to conflict and poverty. Disease was ubiquitous, school was a rarity, and every child knew what it was like to go hungry. It is here that the reader is first introduced to the Hutu-Tutsi ethnic distinction as Deo experienced it.

"I can’t tell you which ones were Tutsis, which Hutus.”

“The killers couldn’t see the difference, too,” whispered Zacharie.

“So they ask. Because they can’t tell. We are the same people.

Oddly enough, Deo did not encounter the word Hutu before middle school. In fact, he did not even know his own “ethnicity” until a year or so later when he asked his father which type their family belonged to. He told him they were Tutsi but said nothing about what that actually meant. Based on his observations, Deo was able to deduce that Hutu and Tutsi were the names of different kinds of people in Burundi and he thought the distinction might have something to do with cows. He tested this theory out on his grandfather, exclaiming that the neighbor was “a great Tutsi because he has so many cows.” He later learned from his brother that being a Tutsi had nothing to do with cows.

It was until medical school, while working as an intern in a rural hospital, that Deo actually experienced the consequence of ethnicity in his country. Burundi’s president had been assassinated and Hutus were killing every Tutsi in sight. Abandoned by his co-workers, Deo endured seven months in the woods and rivers trying to escape the violence. Kidder recounts the months that Deo spent hearing scream after scream, wading through rivers filled with bodies, and running only on primal instincts of survival with such detail that time and time again the reader finds himself asking: What would I have done if I were in Deo’s position? Could I have survived? No.

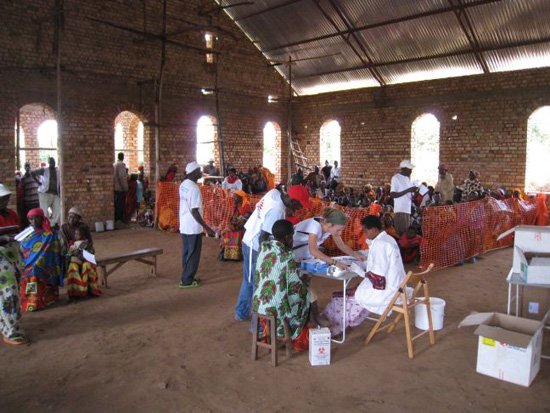

Yet against all odds, Deo did survive. With the help of a French-English dictionary, and the people he met along the way, Deo was able to establish a life in the United States that surpassed all expectation. From profound tragedy, sickness, and starvation in Burundi, to sleeping in Central Park and delivering groceries in New York City, Deo ultimately landed in the home of an American couple and the student body of Columbia University. Nine years later he was enrolled at the Dartmouth School of Medicine. Today, Deo operates Village Health Works, a non-profit dedicated to providing treatment and preventative medical services.

Reflection

The most startling revelation to come from Strength was the arbitrariness of the Hutu-Tutsi distinction. While the author does not immediately provide a historical recount of the country’s ethnic divide, the reader is introduced to the topic through Deo’s own curiosity as a child. We learn that it was not a centuries old racial distinction but a product of the Belgian colonials who created the divide to exploit the country. As a reader, you experience a sense of anger—how could the Belgians allow a hatred they created rise to the level of genocide without intervening? What made it so easy for people who were no different than one another to commit such atrocities? While the questions go partially unanswered, we should commend Kidder for raising the issues.

One of the qualities of Kidder’s writing that I admired was his ability to avoid interjecting his own social commentary where it easily would have fit. Kidder’s narrative style is not forceful; rather, the chapters focusing on Deo’s life growing up in Burundi were given in a straightforward manner—as Deo had experienced it. Kidder did not control the reader’s emotions. Instead, many of the heartbreaking portions of the book were told in a very matter-of-fact tone. His hands-off, unbiased approach in the first section of the book allows the reader to build a connection with the character and to develop his own emotional responses to such stories as people eating grass when there was no food, and of Deo walking barefoot across mountains for fourteen hours just to let their cows eat. For Deo, that was the way of life in Burundi. The level of respect the reader has for him continues to grow from the time he is five years old.

Through Deo’s story, Kidder also touches on the effects, both positive and negative, that living in an impoverished country can have on a person. In Burundi, having a tin roof signaled wealth and those who were able to attend school were among a very select few. With no public healthcare system, sickness was inevitable and, as Deo explained, losing a son, daughter, or mother was a part of the life that the people had grown accustomed to. In an effort to sort the emotions brought with the civil war, Deo found himself frequently grappling with how such inhumane acts could take place in his beloved country. Through Deo, the reader receives a possible explanation for the genocide. His studies at Columbia led him to believe that the Burundian people’s misery was the primary cause of the mayhem experienced in the 1990’s. To Kidder, Deo posed a starting question: How can people think right if they are constantly subjected to pain and deprivation?

Deo’s optimism, if you can call it that, defies any preconceived notion that one might have towards a survivor of genocide. Anger and hatred would be understandable. Instead, Deo never detached himself from the strong ties that came from a community living in poverty—you always gave what you could to those in need. Deo believed that you could learn something good in hard times: here, his lesson was that constant suffering was no way to live. He believed that access to healthcare through a community-run clinic could serve to eliminate some of the suffering that drives people to act out with anger. As was often repeated throughout the book, Deo knew never to say “never again,” but his drive seemed to signify his belief that he owes his people the chance to actually adhere to the motto. In the least, his resolve should induce those who oppose such humanitarian efforts to reevaluate their position.

It may be true that most of the world looks at the people of underdeveloped countries admirably, I have my doubts that is actually the case--at least in practice. Thankfully, books such as Strength operate as a means to humanize the unknown. With Deo, Kidder challenges most of the Western world’s prejudices that these regions are inherently violent and therefore not deserving of intervention. A problem continues to remain, however, if the international legal community is willing to spend an inordinate amount of time trying to differentiate between genocide and an “act of genocide,” and deciding whether intervention is warranted, or if it violates an individual state’s foreign policy.

By detailing the story of Burundi, Kidder dispels the common notion that genocide was unique to just Rwanda. If inaction is viewed as a mistake, there is a chance that public disapproval might incite a quick determination to stop these acts of violence before they evolve into full-scale genocide. Certainly there exists a compelling interest to protect state sovereignty, but that interest should be balanced against a leader’s responsibility to govern within the bounds of human decency. By inadvertently allowing human rights violations to occur, our international system will render any effort to promote the idea that each person has inalienable rights utterly futile.

Conclusion

In the end, Kidder’s story begs the question of what remains. At first, I was skeptical that it was possible for anything to remain with a group of people who had experienced such horrific acts of violence. The book however, altered my position. Kidder’s presentation of Deo’s life proves that memory can act as a powerful tool for rehabilitation. Because the people will never forget what happened in Burundi during the civil war, their memories serve as a means to instigate change. Deo’s experience forced him to determine why his country had fallen victim to violence. After concluding that violence was product of poverty, that the lack of access to basic healthcare only exacerbated the suffering of his community, he decided that the solution for him was to provide what he could. Opening in 2007, Deo’s clinic has served more than 50,000 patients in Burundi.

Still, more remains. With authors like Kidder willing to tell the story of those who have suffered acts of genocide, the commonalities of these tragedies are documented for all to see. If a pattern emerges, the hope of identifying effective preventative measures increases. Through Strength, Kidder allows the greater public to learn more about what it life is like in the regions that all too often become entrenched in civil war. By breathing life into the victims of genocide, the author allows the people of Burundi to become more than just a number to the outside world. It is with that connection that we might have a better chance of ensuring that such massacres do not happen again.

Grab a copy of the book here.

@deviedev, as I mentioned on Steem.chat, I think a post like this would be more powerful for the platform overall if you had an affiliate link to promote the book on Amazon, that way you can help show that this platform generates sales, not just currency that only has value due to speculation.

I explain more about this idea in this post:

https://steemit.com/steemit/@nathanbrown/top-4-ways-whales-can-increase-market-capitalization-of-steem-by-local-currency-expert-and-online-marketer-consultant

I'm posting this here to see how other people like or don't like the idea based on how they up vote or down vote this comment. Might help you determine if you'll get down voted if you try this sort of thing.

Inspiring story, people like these are beyond anything imaginable and books like these can shed some light on the depths of the human spirit.

"Because the people will never forget what happened in Burundi during the civil war, their memories serve as a means to instigate change" I'm afraid i can't share this optimism...

That's fair--although I would like to think that Deo's memory, which lives through his work, helps alleviate the the type suffering that leads to such violence.

Wow. This is a fantastic review. I'm not sure I could read the actual book itself I think parts of it would be too horrifying.

Thank you! There are indeed many horrifying parts, but it's one of those books that is too good to put down.

Heartbreaking...

Exactly, survival under such conditions is top priority, more than anything else...

And kudos to Kidder willing to listen to such heartbreaking stories. And for you to sharing with us.

I definitely want to pick this up now.

Haven't read this but I think about the Rawandin Gennaside all the time because it was such a crazy thing. Its cool to see a book review do so well on Steemit because I red a lot.

I agree! I would love to see more book reviews as time goes by.

lovely thanks for sharing!

Thank you for helping to bring more attention to this!