The India watch story

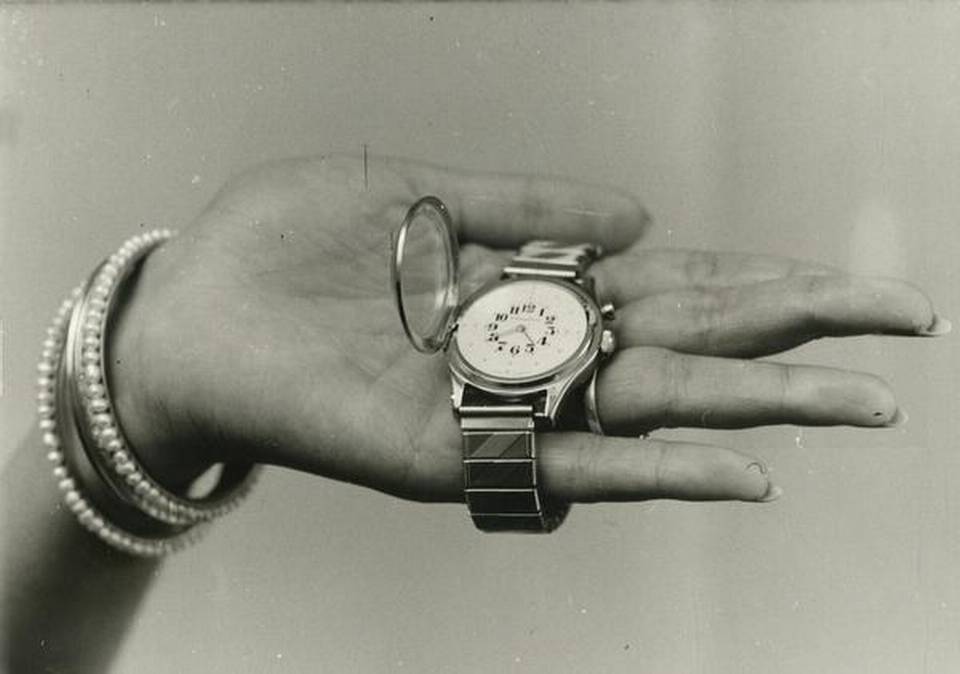

From maharajas fascinated with pocket watches to homegrown watch brands attempting to take on the Swiss, we look at what’s keeping time in the country

Walking the carpeted halls of India’s first watch factory in Bengaluru, I can’t help but compare it to the A Lange & Sohne manufactory I visited in Dresden, Germany, years ago. There it was all glass, steel and stoic silence, while here it’s noisy and quintessentially Indian — I spot the CNC machine sporting remains of namam from the recently concluded Ayudha Puja. And only here would toothpicks be an essential part of the final watch assembly. “Wood is actually the best way to get rid of dust beneath the glass case,” explains Gaurav Mehta, the founder of Jaipur Watch Company (JWC). Of course, the Germans haven’t had to deal with tropical dust.

Mehta says he’s always been experimenting with watches, taking them apart and putting them together again. During one such experiment, the avid collector had slipped an old coin on to the dial — only to receive endless enquiries about his new watch. Sensing an opportunity, he decided to retail his coin watches, sourcing movements and assembling them in Jaipur. JWC, established in 2013, is one of three companies attempting to create a successful homegrown Indian watch brand, the other two being Aiqon, which has been retailing since 2014, and Horpa, that started four months ago. Humble beginnings for a country whose elite had once patronised watchmaking at par with their European counterparts.

Favouring royalty

Francesca Cartier Brickell, who has been piecing together her family’s legacy on the blog creatingcartier.com, tells us of the Delhi Durbar of 1911 — when her great-grandfather, Jacques Cartier, opened boxes of glittering jewels, only to find the maharajas wanted something more simple, Cartier’s silver pocket watch. “While it is Cartier’s jewellery for the maharajas that has received most of the press, its watches were also very popular,” she says. “When the classic tank watch, created by Louis Cartier in 1917 (said to have been inspired by the shape of the tank in World War 1), became popular in London and Paris, the maharajas wanted it too. There were also more unique items created for Indian clients, like embellished versions in enamel or pave diamonds, along with larger timepieces like an order from the Nawab of Rampur for four carriage clocks designed to sound like European cathedral bells!”

![11WKJaipurFlower Watch 3.jpg]

( )

)

It’s not just Cartier though, Swiss brand Longines celebrated 135 years in India, in 2013, with a contest for the oldest Longines watch in the country, while Jaeger LeCoultre prides itself on the fact that their popular Reverso model was created at the request of a polo player here, in 1931.

According to Marc de Panafieu, Brand Director - Middle East, Jaeger-LeCoultre, India has always seen a balance between local traditions and international luxury brands. “The era of late 19th to early-to-mid 20th century was a great market for European luxury brands. The Indian market, dominated by royal families, had absolutely no dearth of wealth or opulence,” he says.

For a country that has had a long standing history with luxury watch brands, it is fair to wonder how the fascination for mechanical watchmaking disappeared. According to Parth Charan, watch editor, GQ magazine, the Indian middle class never got into the cultural aspect because our first mechanical watchmakers, HMT, sourced its movements from Citizen, in an attempt to mass produce. Later, in the ’80s, the influx of quartz movements meant Titan could sell watches for much less, phasing out mechanical watches. In the late ’90s and noughties, brands like Swatch dominated the market and nobody had the time to learn the intricacies of horology when there were cheaper, more efficient alternatives on hand. Today, when well-travelled Indians have begun to appreciate the workings of mechanical movements, Swiss brands are dominating the market.

Teerath Doshi, Director, Helvetica, is also of the opinion that since manufacturing of movements isn’t our strong suit, the dependence on Japanese brands could be one of the reasons why India’s watch culture isn’t as widespread as other countries. “We have good jewellers but not watchmakers, although more people are appreciating fine horology,” he says. The jeweller-watchmaker comparison works because the kind of intricate handwork required for both are similar, and it was, in fact, a jeweller, Louis Cartier, who invented the wristwatch. Interestingly, it’s the gold watch, sold by traditional jewellers, that sells the most here, simply because Indians have an affinity for gold. Today, the Swiss watch industry in India is worth anywhere between ₹1,000 to ₹1,200 crore, adds Doshi. While tourbillons and minute repeaters may not get the average watch buyer excited, value for money, and a chance to stand out, does.

Bolder is better

This could explain a lot about the watch buying culture in India today, where the domestic brand market size is estimated to be around ₹6,500 crore, according to a trade magazine. Charan feels Indians prefer bold watches. They are always looking for the latest ‘new thing’ and, while Swiss brands do come up with new designs, all the grand complications have already been created. The demographic interested in buying these is shrinking. “Niche brands, like Vacheron Constantin for example, bank on the prestige angle and their brand history, but Indians largely prefer big Swiss watches whose complications are visible and whose worth is apparent, like a Hublot,” he says.

Names that are considered ‘mall brands’ in the US, like Tag Heuer, are premium in India, falling in the below ₹4 lakh range, which the middle class aspires to. Take watch enthusiast Sarvanan Govindarajan, who started adding Tissots to his 300-strong HMT collection in 2002, and is now eyeing the Omega Speedmaster Moondust. “Most of my salary goes into buying watches,” he laughs. Bengaluru-based Govindarajan is also a patron of JWC and enjoys the attention his Imperial watch with the coin gets him; he is getting a customised skeleton watch next.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are names like Hublot and Patek Philippe, the target audience for which are extremely limited — because you need an active interest in mechanical watches, as well as money. That’s where things have got a little harder, even for the moneyed connoisseur. Between demonetisation, limits on cash purchases without PAN cards and the latest GST fiasco, there’s an all-round tightening of purse strings. “The Indian watch industry is going through a tough time for the last year and a half,” says Doshi, adding, “What’s selling best are in price points from ₹50,000 to ₹2 lakh, like Rado, Longines, Tissot and Montblanc.”

Harking back to analog

But the slowdown is not a local phenomenon. The industry globally is going through a crisis, which stems from the fact that millennials are less interested in watches. “The last time things were this bad was during the Great Depression,” explains Charan. Today, telling time isn’t a need, it’s mostly aesthetic, so it’s worth wondering how much a person is willing to shell out, he adds.

Designer Michael Foley, who was previously design head for Titan, has a different line of thought. According to him, the average person is surrounded by so much technology, that it’s inevitable they will want something with a little more tangible value. “The appeal of a handmade watch is probably from tech fatigue and the sense of nostalgia it brings,” he says. But one thing that both Charan and Foley agree on is that the future is definitely going to be smartwatches — and Apple Watch overtaking Rolex as the highest-selling time piece in the world is definitely a sign. “This fact is reflected in the industry’s attempt to bring the aesthetics of a good Swiss watch, through pixels and changing watch faces, with a smartwatch’s technical benefits,” says Charan, while Foley points us to Withings (now owned by Nokia), which looks like a regular analog but is an activity tracker that connects to your phone. “It’s a more immersive technology for a smartwatch, and that’s where we’re headed,” he concludes.

Meet the Indian brands

Jaipur Watch Company: Since starting off with the Imperial collection in 2013, JWC has grown and today employs 27 people at its Bengaluru factory. With over seven collections (ranging from a peacock feather-inspired one to a range of pocket watches), Mehta’s favourite part is still bespoke commissions. He has received requests ranging from the creative to the bizarre — one client asked for a watch with diamond petals that rise and fall like a flower, and another wanted Barack Obama’s face engraved on the dial. This being India, he gets countless requests for gods and goddesses, and depending on the budget and requirement, he works with embossed gold dials and diamond-studded ones.

Aiqon: Despite a background in finance, Chinmay Shah didn’t want to work with numbers. For him, watches are a 3D canvas to apply his creativity. The first watch he designed was Maximum City 1888, a rose gold piece with a square dial, inspired by the architecture of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. Priced at a modest ₹3,200, he says his pieces target the below ₹10,000 range.“ The Indian watch sector is predominantly brand driven,” he admits, while adding that the average Indian consumer, for watches at least, is more driven by the way it looks than facets like design or functionality. “And of course, Indians customers always ask about servicing,” he adds.

Aiqon: Despite a background in finance, Chinmay Shah didn’t want to work with numbers. For him, watches are a 3D canvas to apply his creativity. The first watch he designed was Maximum City 1888, a rose gold piece with a square dial, inspired by the architecture of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. Priced at a modest ₹3,200, he says his pieces target the below ₹10,000 range.“ The Indian watch sector is predominantly brand driven,” he admits, while adding that the average Indian consumer, for watches at least, is more driven by the way it looks than facets like design or functionality. “And of course, Indians customers always ask about servicing,” he adds.

Horpa: Deepak Choudhary and his partner Rajeev Asrani combined the words ‘horology’ and ‘passion’ to name their brand Horpa. It was born out of their mutual love for watches. While the former is a CA by profession, the latter has been retailing luxury watch brands for the last 20 years. Choudhary says they were inspired by independent watchmakers from Switzerland like MB&F, who do limited number of pieces, as well as Hublot’s fusion contemporary makes. Their first collection, called C1, is a 45mm men’s chronograph, with seven variants, priced at ₹14,500 and ₹16,500, which he considers introductory. Horpa has sold 150 pieces in the last four months, mostly via word-of-mouth and social media.

Congratulations @thirupathiboyire! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP