My First High School Research Paper: Trumpets of the Renaissance and Baroque

My beloved high school English teacher, the late Eva Meredith, impacted many lives and passed away just last month. I'm sure she would be happy to see her students' work published, and she would've blown off a lot of Steem here instead of other social media platforms.

For 43 years, I've had this manuscript on file and Steemit is a way to get it published. It also serves as a way for me to practice formatting posts on Steemit.

Ahhhhh....it feels good to get it off my "to do" list and share it here. I want to learn how to get text to wrap around pictures and to center figures and text. I copied and pasted the document into the post editor and had to convert my drawings to URLs. Then I had to denote paragraphs and designate headings. In other words, it wasn't a simple copy & paste process.

Any help on how to do that would be appreciated. I am saving my good stuff until I can get more proficient at presentation of the material.

Here is the research paper and my illustrations from 1975 as a Senior at Allen County-Scottsville High School:

Trumpets of the Renaissance and Baroque

Abstract

No musical has undergone more radical changes since the Baroque era than the trumpet. Now a valved instrument with a total length somewhat over four feet, it was during the Baroque era a valveless instrument with a total length of about seven feet. On a valveless brass instrument it is possible by lip tension alone to produce a series of tones with a fixed relationship to one another. Composers took advantage of these limitations to establish the trumpet as a unique instrument, such that figures written especially for the trumpet would betray their origins if played on another, less brilliant instrument. This discussion will trace the development of the trumpet and illuminate its varied importance in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries.

Text

In all the history of the trumpet, the years between 1500 and 1750 can be said to be by far the most glorious. Aside from being one of the most favored of all instruments by Renaissance and Baroque composers, the trumpet was primarily a coveted luxury for kings, churches, and wealthy municipalities. Although the instrument was without valves until their invention in the early nineteenth century, and therefore could sound only the natural harmonics relative to the key in which the instrument was pitched, the ingenious imaginations of composers played a large part in establishing the trumpet as a virtuous solo instrument. The secret techniques employed by trumpeters were jealously guarded by the aristocratic trumpeter’s guilds, which played an important part in the development of the trumpet and its music until the end of the eighteenth century.

The trumpet has assumed various shapes and forms throughout its history. However, there are distinct periods in its evolutionary development, i.e. the first, when until about the fifteenth century the instrument was a straight tube approximately four feet in length. This was first adopted by the Romans with the bucina, a straight tube of bone or wood with an upturned flair at one end. The advancement of metallurgy later enables trumpet makers to bend the tube. Throughout the fifteenth century and the first third of the sixteenth century, the tube was bent in an “S” shape in one plane, and the three parallel sections were connected by two U-bends. The third form still exists today: The S-shaped trumpet was folded so that the first and third pipes were superimposed, and separated by a brace so that they lie about three inches apart (5). These three periods will now be discussed in detail.

The history of the trumpet before the sixteenth century is somewhat obscure. Since there are few, if any, surviving specimens before 1500, virtually all information we have is iconographic. The trumpet before the late fourteenth century, being a straight length of cylindrical tubing with a flair at one end, resembled our modern coach or post horn. With a length of approximately four feet, the instrument was usually pitched in C, and had a range up to about the seventh or eight harmonic (3). Therefore only simple, fanfare-like passages could be played on it. Had the tube been longer, an improved range, and thereby more melodic possibilities could have been achieved with the instrument. However, with lengthening of the tube came increased unmanageability, which ultimately, along with the advancement of metallurgical techniques, gave rise to the bending of the tube along its length.

The earliest evidence of a curved trumpet is a carved figure of a choir seat in Worceister cathedral. Estimated to date from the late thirteenth century, one of the figures in the picture is carrying a trumpet folded in an “S” shape. This form seems to have remained until the first third of the sixteenth century. However, such a construction is fragile, and later succumbed to the contemporary fashion of superimposing the first and third sections of tubing (6).

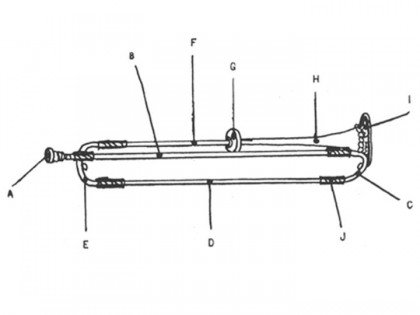

Figure 1. Nomenclature of the Baroque Trumpet. A: mouthpiece. B: mouthpipe, or first yard. C: first bow. D: middlepipe, or second yard. E: second bow. F: bellpipe, or second yard. G: boss. H: bell. I: garland. J: garnishes.

Throughout the remainder of this paper, the nomenclature described in Figure 1 will be used. The mouthpipe and bellpipe were rotated toward each other to arrive at the configuration that remained throughout the Baroque period and even after the advent of valves in the early 1800s. The three parallel sections, or yards, were connected by two U-bends. The first yard and third were separated by only a small block of wood, only two or three inches in length, and wound with the piece of cord which was normally used for carrying the instrument (5). This lack of rigidity probably resulted from the (mistaken?) idea that the trumpet would sound more freely if allowed to vibrate. Contrary to some opinions, it was not due to the manufacturer’s inability to secure the sections of the tube more sturdily as evidenced by the fact that on most trumpets of this period, the first bow is connected to the bell by only a small loop of wire. Had the craftsman chosen to do so, he needed only to have soldered the two together to produce a rigid stay (3)

Several different types of trumpet were in common use throughout the Renaissance and Baroque. Having no way to instantaneously alter the length of the vibrating air column, these natural trumpets sounded only the notes belonging to the harmonic series. In addition to severely limiting the range, they could only be played in whatever key the instrument was pitched (usually D or C, with some shorter and higher pitched in E-flat, F, or G). Therefore it became necessary to devise some method of playing the missing tones. Perhaps the most efficient of these was the implementation of the telescopic slide in the first yard, similar to the device found on the trombone (sackbut). A surviving specimen of such a Zugtrompete, or tromba da tiarsi, is preserved in the Instrumenten Museum in Berlin. The slide is inserted telescopically into the first yard, and the entire body of the instrument is drawn back and forth with the left hand. The right hand held the mouthpiece steady against the embouchure. However, this becomes rather cumbersome as the distance the instrument must be extended in order to effectively alter the series is somewhat long. Thus the Zugtrompete was no not held in favor over the natural trumpet. J.S. Bach scored the instrument for a few chorale parts, and Henry Purcell wrote a canzona for the funeral of Queen Mary which required a “flat trumpet,” presumably meaning a slide trumpet due to the frequent occurrence of nonharmonic tones (5).

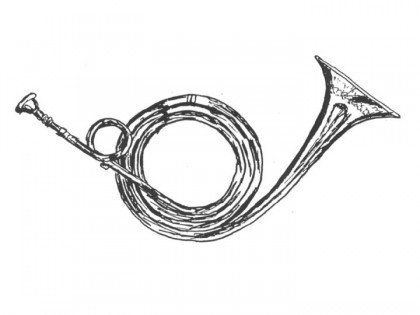

Another innovation appeared in the late sixteenth century. The trumpet was coiled in horn fashion, with the bell facing slightly toward the player as shown in Figure 2. The intended technique was for these Jagertrompeten was to insert the hand into the bell, thereby raising the tone one half step. However, this resulted in muffling the trumpets brilliant sonority; the result was a timbre very similar to the natural horn. The instrument could be played in the same manner as the natural trumpet, and was widely accepted because of its noncumbersomeness. It is the instrument shown in Haussman’s famous portrait of Gottfried Reiche, Bach’s principal trumpeter. Also, Jagertrompeten were pitched in E-flat and called clarino piccolo. Schelle scores one in his “Solve solis arientis” and gives an explanatory note on the instrument (7).

Figure 2. Jagertrompete, or coiled hunter’s trumpet.

Throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries the foremost center for musical instrument making was Nuremburg. Trumpets made in Nuremburg were found in every major court from England to Saxony. However, considered superior to all instruments from the late seventeenth to the nineteenth century were the trumpets made by the Haas family (1). Kammertrompeter Johann Wilhelm Haas became a master of trumpet making in 1676. He established a shop in the Kreuzgasse, a street just south of the Regnitz River, near Hallertorbrücke. The family tradition was passed down from generation to generation until it ended with Johann Wilheim Haas’ great-grandson, Johann Adam Haas. As four craftsmen, Johann Wilhelm, Wolf Wilhelm, Earnst Johann Conrad, and Johann Adam used the original shop established by Johann Wilhelm. Every Haas trumpet bore the same type of ornamentation; the Haas trademark was a running hare, a play on the German world hase, meaning “hare.” (7).

Generally the Haas’s made two types of trumpets: Simple, i.e., without a great deal of ornamentation, and ornate. The simple instruments were intended for field and military use, while the ornate trumpets were meant to be used for ceremonial affairs of the court. The garnishes found on most ornate trumpets were usually fluted and had a spiral design. The ends were usually scalloped, often with an element of the design found on the garland, and the garnishes often had around each end, just before the scroll pattern, and engraved ring with the same pattern as found on the bell rim (7).

The engraved floral pattern of leaves, a flower with the appearance of a tulip and an object resembling a pomegranate were indicative of a Haas trumpet. Any or all of these would always be found on a Haas trumpet. The more elaborate instruments of the Haas’s frequently had cast angel heads, either three or four, soldered to the garland and the bass. However, the absence of theses angel heads did not preclude an instrument from being made by a Haas (7) The instrument in Figure 3 is one such ornate trumpet.

Figure 3. Trumpet in D by Wolf Wilheim Haas (1681-1760).

All three of the craftsmen after Johann Wilhelm placed the founder’s initials somewhere on the garland. They usually were found near the picture of the hare, and probably came about as a manner of respect to the initiator of the dynasty. The main difference in ornamentation between the trumpets of all four Haas’s was the hare. Johann Wilhelm pictured the hare in a springing position, and it evolved to a sitting position, and it evolved to a sitting position with Johann Adam. When valve and key trumpets began to be of general use, Haas trumpets gradually became obsolete. Hence, none of Johan Adam Haas’s sons continued the profession, so the traditional art ended with Johann Adam’s death in 1817 (7)

Other than the Haas’s there are few very prominent figures in the art of trumpet making. One keen experimenter, however, was Anton Schnitzer the Younger of Nuremberg. Many methods were attempted of bending the tube into various shapes, but the configuration devised by Schnitzer with the trumpet shown in Figure 4 is unique, and partially accounts for his popularity as a trumpet maker in the late renaissance. The instrument is pitched in E flat and coi8led in pretzel shape, composing a large figure eight with two circles at the sides. Compared with the length of the tube, 208 cm, the bell diameter is unusually small: 10 cm. This accounts for its mellow timbre and dark tone color. Schnitzer trumpets were especially popular for ensemble use because of this quality. The instrument in Figure 4 is preserved in the Kuntzhistoricshes Museum, Vienna (8).

Figure 4. Trumpet made by Anton Schnitzer in 1598. Marked: “Macht Antoni Schnitzer in Nvrmberg.” Key: E flat. Tube length: 208 cm. Bell Diameter: 10 cm.

In the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, the “Guild of Trumpeters” was particularly exclusive. Its respected members were often associated with royalty, and played an important role in military affairs and the everyday lives of all the townspeople. Aside from providing entertainment and ceremonial music for special occasions, some trumpeters help positions of standing watch over the town and warning the citizens of fire or attack. All trumpeters were assigned to play only in a certain register on their instruments, and would specialize their technique for playing only those notes. Certain laws restricted members of the guild, and allowed them special privileges enjoyed by no one else. The art of trumpet playing was handed down through families, and therefore was considered quite an honorable profession. Trumpeters divided themselves into two general categories: Feldtrompeter and Kammertrompeter (field trumpeter and concert trumpeter, respectively). The feldtrompeters were important military figures. By blowing certain melodies on their instruments, they would signal the troops to retreat or attack. Feldtrompeters need not have been able to read music as their simple, fanfare-like passages could have easily been memorized. On the other hand, the kammertompeters and were skilled musicians and highly respected artists. They lived with the king in his castle and provided music for meals, sporting events, entertainment, weddings, and other special occasions. Sometimes kings had trumpet and tympani corps to provide ceremonial music for impressive events. Kammertrompeters had clearly defined duties to perform at the court, as researched by Smithers (7):

“When there were no guests in the court the trumpeters and a tympanist had only one service to perform on weekdays. The entire trumpet corps and the tympani were obliged to perform at special events. On the birthdays of the resident nobles as well as on special feast days the [kammertrompeters] were also instructed to provide special ceremonial music. At the beginning of the afternoon and evening meals the Tafelblasen often consisted of short pieces for two or three trumpets and tympani. At those courts where music was particularly important, the [kammertrompeters] were from time to time required to accompany the chapel choir as well as join the court orchestra in theatrical productions. In the lesser courts the duties of the second-rank trumpeters might include assignments of lesser distinction: working in the kitchens or in some servile capacity within the court or on the nobleman’s estate.”

The registers of the trumpet were divided into two sections: Principale and clarino. The principale part was played by the feldtrompeter, and consisted of notes in the middle and lower registers. The clarino part was played s only by veritable virtuosos. The superlative few kammertrompeters who were allowed to play in the clarino range enjoyed special privileges such as fine silk and velvet uniforms, and private suites in the king’s castle. Any kammertrompeter convicted of a minor crime had such prestige in the court that he could easily escape punishment. Any feldtrompeter caught playing a clarino part could be subjected to severe forfeits or even torture (2). Also, certain restrictions were placed on blowing unofficial trumpet calls after the hour of curfew, due to the fact that they might have been misinterpreted as warning signals (7)

Of particular importance to sixteenth and seventeenth century towns were the feldtrompeters who were assigned to be tower watchmen (Türmer). Their primary responsibility was to keep watch over the particular area of the town each was assigned to watch. They stood in strategically located towers and warned citizens of any unusual danger by sounding certain calls on their trumpets (7). Tower watchmen were required to take an oath before assuming duty. Below is the oath of a trumpeter assigned to watch over the German city of Wismar, 1586 (7).

“I, Christopher Westphall swear that I shall be true, obedient, and loyal to the honourable council of the town of Wismar, to bear in mind their and the town’s best interest, and to avert harm to the best of my ability while on the tower of St. Nicholas, where I have been appointed to tower-watch. I swear two watch carefully day and night, to look after light and fire with all diligence so that no harm may come to the town and the church from them; in other respects I also swear to behave modestly and peacefully with everyone and to lead an honourable and respectable life, so help me God.”

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the trumpet’s noble status was falling, and it finally lost importance as a major orchestral instrument until valves became standard on the instrument to greatly extend its compass in the early twentieth century. The nobility of trumpeters became archaic, the aristocratic Trumpeters’ Guild went out of existence, and past glories were forgotten.

References

1. Altenburg, Johann Earnst, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Herdicsh-musikalischen Trompeter- und Pauker-Kunst, Halle, 1795. Translated by Edward H. Tarr, Nashville; The Brass Press, 1974.

2. Bragard, Roger and De Hen, Ferdinand J. Musical Instruments in Art and History. New York: The Viking Press, 1968.

3. Carse, Adam. Musical Wind Instruments. New York: De Capo Press, 2965

4. Edgerly, Beatrice. From the Hunter’s Bow. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1942.

5. Galpin, Francis W. A Textbook of European Musical Insruments. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc.,, 1937.

6. Sachs, Curt. The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1940.

7. Smithers, Don. The Music and History of the Baroque Trumpet before 1721. Great Britain: Aldine Press, Letchworth, Hearts, 1973.

8. Winternitz, Emanuel. Musical Instruments of the Western World. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1967.

Congratulations @qiyi! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

To support your work, I also upvoted your post!

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP