Why My Parents Still Run With Scissors: An Anecdotal Analysis of Rational Risk Assessment

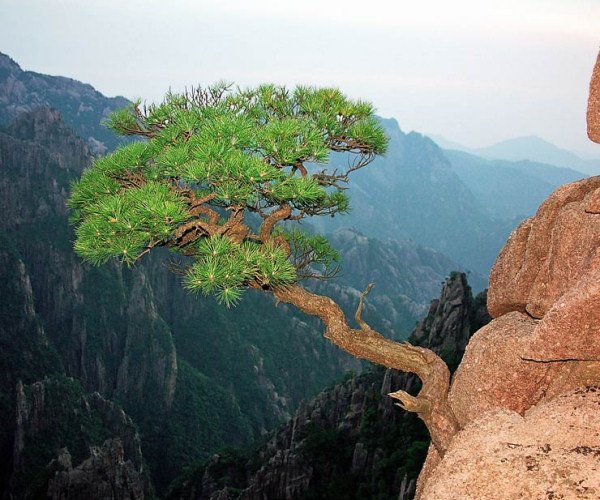

Hanging From a Branch Over a Cliff

Clutching a thick tree branch with my arms and legs, I shook in fear. Every muscle tense and gripping with all my might, but feeling so weak with a vast and empty canyon looming below. One slip, one wrong move, and I would be falling for quite some time. How did I get to this pernicious place in the jungles of Costa Rica?Someone told me to.

My brother is an adventurer, a volcanologist, and a geologist. He has taken me on many exciting exploits, including this backpacking trip. As we walked up a hill, there was a large tree overhanging a cliff with an unreliable rope ladder blowing back and forth in the wind on its trunk. “Let’s climb up the tree,” he said nonchalantly.

So I went first while my brother held the ladder in place, slowly realizing the terror I felt as I neared the top rungs. To make room for my sister-in-law, I had to climb out on a large branch that was directly over the cliff. Oh shit, I thought as I looked below me and saw nothing but air for a very long way. Next was my sister-in-law, then my brother. What my brother neglected to take into consideration was that no one could hold the ladder in place for him. As he blew back and forth, over the cliff, back over the ground, and then over the cliff again, I heard him make a few surprised grunts. But he made it to the top, as he always does in these situations.

I don’t remember the view that day, only my fear.

Humans interpret information and asses risk with one of two processes. The first, fast process is the sub-cognitive intuitive emotional brain. The second process is the slow rational cognitive process of accessing information. For more about these systems of thought, see Graham W. Boyd’s article The Brain’s Risk/Reward System Makes Our Choices, Not Us

Think of it this way: have you ever walked into a door that is pull, not push? When you walk into the door you are using the first process. Your brain uses intuition and expects the door to push open. After you push the un-push-able door, you think how does this open? That’s the second process.

In the scenario above, my brother was our guide. He was seven years older than me and I looked up to him. When he said climb, I climbed. It wasn’t until I was dangling from a limb high above a cliff that my second rational cognitive process kicked in. That’s the point where I recognized the risk.

Why did it take so long for me to become fearful since the emotional/intuitive process is quicker? Simple, my brain was trained on a sub-cognitive level to trust my brother. My brain assumed his decisions could be accepted on impulse as correct evaluations of the risk and reward of these types of scenarios.

Jumping Off the Ledge

“Jump, jump!” My mother yelled as my toes peaked over the high rocky ledge of the quarry. The opaque surface of the water below glistened in the sunlight. “Your sister did it already, what are you afraid of?” I thought back to the multiple signs we passed on the walk in: No swimming or jumping in the quarry, unseen rocks below the surface.

Breathing in deeply, I clenched my fists together and jumped.

The skin in between my toes felt like it was tearing off as I entered the water below and my bathing suit went way too uncomfortably high. I figured out how to get myself upright underwater and made my way to the surface.

My head popped out of the water and I heard cheering. I did it. But I wasn’t proud. Why did I just do that? I thought to myself.

Someone told me to.

Jumping off a cliff into dangerous waters is a bad idea. It only took my brain a split second to make that realization. As I stood staring over the cliff, my cognitive process began to work, remembering the signs. Then hearing my mother’s voice: “Jump!” I thought, maybe this isn’t stupid, she is my mother. Hearing “Your sister did it” furthered my thought process – well she was okay. In this case I allowed my cognitive function to be coerced by outside influences and I jumped.

I had absolutely no idea where the hidden rocks were and how likely they were to kill or injure me. All I know is that my sister, an n of 1, made it.

Adam Elgar, professor of philosophy at Princeton University, would explain quantifying this type of risk something like this:

The probability of hitting a hidden rock is not a direct probability, since I, the subject, had no detailed information on the quarry’s underwater topography, other than what the signs provided. There are underwater rocks that are dangerous. There is no reason to believe the signs are not trustworthy. With the information I had, there was no way of determining a statistic such as 1 in 3 people who jump from the same spot with a similar force do hit rocks. In fact, the probability from my position could have been 10%, 32%, 47%, or 90%. I had no way of determining that.

If I had shut out external influences and attempted to quantify the probability that I would safely land in the water, it would have spanned a large interval of values like [10%, 90%] because of my lack of information. Once I determined this level of unknown risk, it should have affected my assessment of risk more than the subjective influence of my mother.

Standing on the ledge, outside subjective stimuli effected my cognitive assessment of the situation by creating a new risk reward paradigm. If I did not jump, I would have to deal with the wrath and ridicule of my overbearing mother. If I jumped, I could die, be injured, or be fine, but I would not have to deal with my mother.

See this article: Subjective Probabilities should be Sharp for more details about this type of risk and probability evaluation.

Eight Go Up, Seven Come Down

“It’s going to be a big storm out there today!” I heard the weather forecaster say. “Heavy rain, high winds, and thunderstorms - it’s a good day to stay inside,” he continued. But my family had planned a bike ride down the side of a mountain in NH, and there was no stopping them. My husband, an experienced rider, protested about going and suggested the conditions were too dangerous for the family. He shouldn’t have bothered. Once my mother made a decision, no amount of reason could dissuade her.The car ride up was filled with innocuous irrelevant chatter. As the thunder softly rumbled, seemingly no one was aware of the fatuity of our upcoming escapade. While rain started spitting from the sky, we disembarked from our cars and unloaded the bicycles.

Impatience grew in my mother as it took my father more than a few minutes to blow up all of the bike tires on the top of the mountain. “It’s a good thing we thought to bring this pump,” he chuckled. Forethought tended to be lacking in these sort of ventures in my family.

Finally, with a slick wet layer of rain on top of the paved path, we were ready to go. In a long single file line we started down the mountain - my mother leading the way, followed by my sister and her husband, my husband and sister-in-law, then myself, my dad, and my older brother bringing up the rear.

I gingerly pressed my brakes, cautiously navigating the turns and steep slopes. We were not a mountain biking family and this was certainly out of my comfort zone in the current conditions. The thunder intensified and the sound of the rain became noticeably louder against the pavement. The rest of my family sped up, leaving me in the middle, followed by my father and brother a distance back.

A large downhill slope came upon us quickly, with a slight turn onto a bridge at the bottom. I slowed on the hill, fearful of skidding out at the bottom with the wet path. I made it over the bridge and about a half mile after that met the rest of my family in a large opening on the trail. We all got off our bikes and waited for my brother and dad to join us.

We waited. And waited. And waited some more. The rest of my family casually talked about what was taking them so long and what we would do once they arrived.

Suddenly, I had a deep-seated intrinsic sensation that something was wrong. “I am going to check,” I quickly mumbled under my breath as I started jogging up the path. I ran faster and faster, each step confirming in my mind the innate feeling of tragedy I knew lay ahead.

Finally, I saw my brother standing in the path. I glanced down and saw my dad laying on the ground, not moving. As I ran closer, I saw his face, pale white, and his eyes, eerily open. “Dad..?” I asked softly. It was silent for what seemed like an eternity, and then he faintly grunted. He’s alive, I thought as a wave of relief washed over me.

My father began writhing in pain. My brother lifted his head and neck and put a backpack underneath to try to give him comfort. What are you doing? You could paralyze him! I thought to myself. But I myself was paralyzed in fear and couldn’t find the words to speak.

My husband arrived on the scene shortly after and immediately declared, “we need to call an ambulance.” My dad could barely breathe at this point, but he managed to get out a choked surly statement: “No, my insurance won’t cover it up here.” My brother, my husband, and I all just looked at each other, not sure what to do. With the realization that my father couldn’t move and we wouldn’t be able to get him off this mountain, we finally called the ambulance.

They managed to walk to our location from their rig and brought my father out on a stretcher. Later at the hospital, we found out he had some broken ribs and a punctured, collapsed lung. He had skidded out trying to turn onto the bridge at the bottom of the hill and had run into the fencing on the side of the bridge.

As I looked at him lying there in the emergency room hospital bed, thinking about his collapsed lung and why he could barely breathe, wondering what would happen next, I couldn’t help but ask myself: How did I let myself get into this mess?

Someone told me to.

My family wanted to go on a bike ride, they thought it would be a fun trip to the mountains, and they told me to go. Why wouldn’t I?

“Risk is an unwanted event which may or may not occur.” Risk and reward is when we weigh the potential benefits versus the risk of a negative outcome. In finance and investment, we weigh risk and reward in terms of numbers, strategy, profitability, game theory, and analysis. In life, our evaluations are much more fluid and have consequences far outside the financial realm, often dealing with far fewer concrete facts.

Subjective, emotional, intuitive decisions led to my father’s hospitalization. The exact danger could not be cognitively calculated before the mountain bike descent. It was clear that it was a riskier day than average and my parents, in their experience and age level, created a higher risk. The second we suggested it might be unsafe, my mother’s mind was made up - we were all going to ride down that mountain.

At what point in our lives do we finally stop doing things just because we are told to? What causes that switch to go off in our head that makes us realize we have our own brain, logic, and thoughts and can (and should) make decisions for ourselves? How is it possible that we can so blindly listen and follow into such risky and perilous situations?

“In decision theory, a decision is said to be made ‘under risk’ if the relevant probabilities are available and ‘under uncertainty’ if they are unavailable or only partially available. Partially determined probabilities are sometimes expressed with probability intervals, e.g., ‘the probability of rain tomorrow is between 0.1 and 0.4.’” Risk Stanford Encyclopedia of Philsophy

We are always evaluating situations under both risk and uncertainty. There are always known and unknown probabilities. I would propose that sound logic, both intuitive and cognitive, needs to be used. While advice from the wise is important, we should remember paradigms like my first two stories, where both the emotional/intuitive and the cognitive were subject to outside influences from substandard subjective input.

In the mountain biking story, my very dominant mother weighed, albeit intuitively, her desires to choose and control plans as greater than the risk.

Astonishingly, my parents still laugh about my father’s near death experience. They still cannot evaluate the risk even after seeing a very negative outcome. The typical problem with risk models is weighing the risk versus reward when not knowing the outcome. In hindsight, it should be easy. Riding down the mountain was ill-advised under those conditions.

Unfortunately, my parents have untrained cognitive and intuitive risk evaluation mechanisms in their brains. My parents are actualists.

“To exemplify this approach, consider a decision whether or not to reinforce a bridge before it is being used for a single, very heavy transport. There is a 50% risk that the bridge will fall down if it is not reinforced. Suppose that a decision is made not to reinforce the bridge and that everything goes well; the bridge is not damaged. According to the actualist approach, the decision was right. Example from Risk, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

My parents quite often do something that most people would consider dangerous and explain their actions by saying, “well no one got hurt.” But, as in the bridge example, the Stanford Encyclopedia points out that the actualist approach “…is, of course, contrary to common moral intuitions.” The problem with the actualist approach is that it disregards the continuity of life. “All reasonable systems of moral obligations will contain a fairly general prohibition against actions that kill another person,” (Stanford Encyclopedia) and I propose injure another person without warrant.

We should not allow low quality outside influences to affect our risk assessment. At a certain point in life, people must start making their own decisions and training both their cognitive and intuitive mind to evaluate risk properly.

To ask nothing. To expect nothing. To depend on nothing

To understand nothing. :)

Wow. It seems that your family is extremely lucky. I am glad your father ended up recovering, it could have easily been worse.

Thanks, yes they are very lucky and unfortunately they use their past luck to condone stupid choices.

Wow, I'm sorry I'm not the only one with a pain in the arse for a mother.

haha, thanks. My daughter has a pain in the arse mother too. Just kidding (I hope). :)

I suppose we should thank them for indirectly teaching us what not to do. I have one daughter and I confess that I too am occasionally a pain in her butt ;)

glad the outcome was not detrimental.

somehow, as a kid we have less fear and try sorts of things and as we get older fear sets in and many of us stop trying. i don't know which is better.