The Songwriter's Son, My Life as Near as I can Remember it, Part Two

These are chapters from my life, and thoughts about what it all means to me now. You can find part one here.

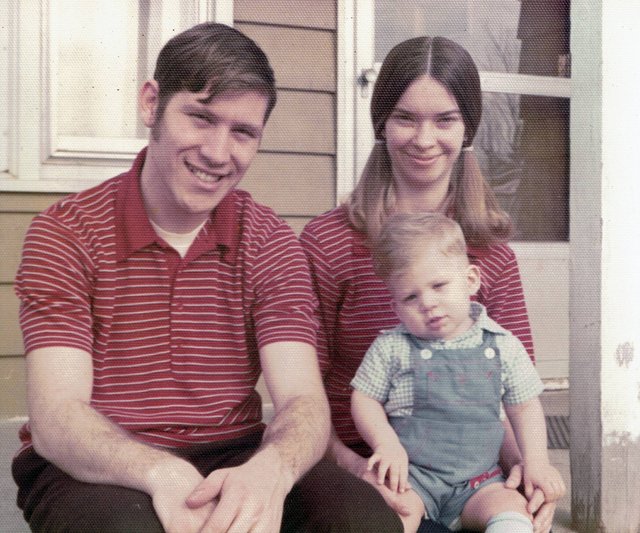

On July 20th, 1969, something amazing took place. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldren became the first humans to walk on the moon, and my dad celebrated his 21st birthday. Just a few weeks away from their upcoming wedding on August 3rd, my future parents sat in the living room of an older couple from their church and watched as the event was broadcast to the world. Two years and eight days later, I would come into their lives.

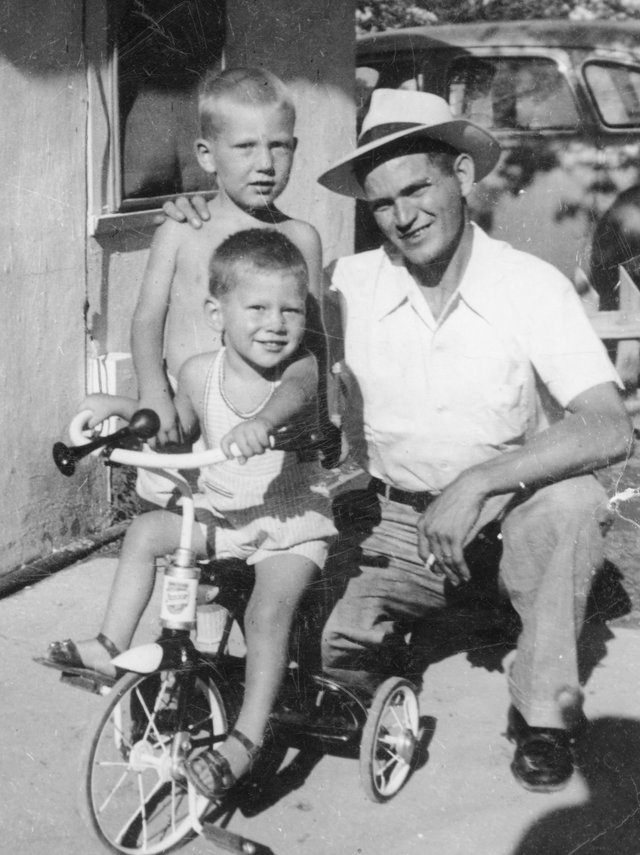

My dad was born in Shawnee Oklahoma, a town about an hour from Oklahoma City, to Itha Hope O’neil, Frederick and a man who I only know as Mr. Frederick. I never asked for more. My dad didn’t talk about his father, he never really knew him. He said he was a drunk who spent food money on booze one too many times, something Judy (the name his mother went by) couldn’t tolerate, so she asked him to leave and not come back.

The man he called Dad, came into his life sometime before his third birthday, I was never clear on the details. Howard Rex Morris was a good man. He smelled like tobacco and he had the hardened, crinkled visage of a Cherokee, with leathery skin and a slanted smile that made his eyes into tiny crescent slits. He liked to laugh at his own jokes. He was not a big man, but he seemed strong to me, confident, in the way a man who knows what he knows is.

My dad met his father only once after that, in El Reno Oklahoma, somewhere around my thirteenth birthday. We had just moved to Oklahoma from Kansas when he got a call that his father didn’t have long to live and that he wanted to see him. So, we got in the car and drove an hour to sit in a driveway of a typical, small, white frame Oklahoma, small town, house, with a screened in porch. Dad went in first.

He wasn’t at all sure what to expect, he seemed nervous as he kissed my mother. She explained that we would wait in the car and if he wanted us to go in, we would. I wasn’t too happy about that. I’m nosey by nature and out of curiosity, I wanted to get a peek at the man I’d come from. But, even as much drama as I was fond of stirring up at thirteen, I knew this was a time to let Dad do what he needed to do.

I watched the door, waiting for the sign to come in, some semblance of welcome. A small, colorless woman in an apron and long white hair tied up in a bun let him into the house. He stayed twelve minutes, I timed it. When he came back to the car, he didn’t say anything, just sat in the seat, shoulders softly bouncing as he wept, I can still see my mother’s wedding ring as her hand rested on his arm, he was wearing a tan jacket.

We never really talked much about it. He told me once that he had walked into a darkened room, said hello to a strange old man, who just sat in a worn-out arm chair and stared at him, stonily, without saying much. He hadn’t brought us in, because, he didn’t want us to know this man, this man, to him, was not his father. We knew our grandfather Howard Rex Morris, the man my Dad had always thought of as his Dad, and that was enough.

Later, he would say that he always wondered why he never heard from him. From things his mother hinted at, he guessed he’d gone to prison. There’s a maximum security federal penitentiary in El Reno, he assumed his father had recently been released, before asking to see him. I never enquired about the rest of his family, it just didn’t seem like it mattered. It’s odd to me, to not be curious about them. I’m pretty much curious about anything, or anyone I don’t know, it’s like a disease, but somehow, like a wolf leaves the carcass of a diseased kill whole, I just know I don’t want to know.

Like pretty much every boy that had a decent relationship with their father, and a good number of those that didn’t, I worshipped the ground he walked on. Not literally, of course, I’d been taught better, the first commandment and all, but, when I was a boy, he was as close to perfect as I could imagine. Later, my opinion would be almost reversed, as is sometimes the case with fathers and sons, I wish it could have been different.

He could stand in a room of a hundred people and hold their attention, well, most of them, for an hour every Sunday morning, evening, and Wednesday nights. He could shine shoes, dig out a splinter, catch a worm, then use it to catch a fish, shoot a rabbit, then skin it, throw a knife, build just about anything I figured, throw a perfect pitch, change his own sparkplugs and talk to God.

But, the most magical ability the man possessed, in my young eyes, was the ability to write a song. He had an old Checkmate G 235 steel string guitar, a Japanese knockoff of a Gibson Monarch, with a red sunburst paintjob, and a double pick guard, with white climbing vines and gold flowers. He could play almost any song and sing it, or so it seemed to me. Sometimes, he’d pick it up and start playing, then he’d whistle a tune that sounded so polished I’d ask him what it was.

“Just something I made up,” he’d smile.

“Right now?”

“Right now.”

It was hard for me to imagine. But, after watching him do it, I realized, that must be how all the songs I’d ever heard came to be. Somebody, somewhere made them up. And, I figured, the same was true with building things, and making things, somebody somewhere came up with an idea and just did it. It might seem like that takes some of the magic out of the world, but for me, it made the people I saw every day into super heroes.

Here I was a shorter version of a species that was capable of creating just about anything with a little bit of effort. So, I learned to whistle, and I’d sit and whistle my own song.

“What’s that?” he’d ask.

“I made it up.”

“It’s pretty good.”

And occasionally, he’d drag out the big, black, pressed paper case with the faux leather texture and the brass colored buckles and hinges and he’d open it up and strum along. It was a big dreadnought guitar, with a bright, shiny sound and to my ears, his playing was so good I wondered why he told stories, instead of playing music for people everywhere. And when he’d tell me he wasn’t quite that good, I couldn’t imagine it.

I’d listen to him write songs, stopping every little while to jot down a lyric or two with a Bic pen in a lined, spiral notebook. He’d chew on the blue pen cap as he worked, tucking the pen behind his ear between lines. He liked John Denver and as I listen to Denver’s earlier stuff now, I hear my father in a lot of ways.

We listened to a lot of music too. One year for Christmas, my parents bought a Sears stereo, with a multi-speed record player, a big lighted dial radio receiver, and there on the front, was a funny slot, with a little flap, for 8-track cassettes. We’d get them from the RCA record club every month to try them out. We’d listen to them, and if we wanted them, we’d keep them and pay a little extra, if not, they got sent back.

We had Roy Clark, John Denver, Roger Miller, The Lettermen, and a few others that didn’t last long enough for me to remember. 8-tracks were great, until they weren’t, and then they were done. My dad attempted to patch a few with clear tape, as he did with cassettes that hit a snag, but they’d always warble along, until they got caught in the player and required minor mechanical surgery to remove them.

I remember the little magazine that would come with the pictures of tapes you could order up. There were hundreds of them, and of course, we picked the pictures we liked best. Most of our choices were ignored, but on one occasion, we got lucky. My brother Steve and I were sitting, looking through the tape cover images, me reading song titles, and every few minutes, we ’d share a selection with mom.

“Mom, how about this one!”

“No, I don’t think you’d like it.”

“This one?”

“That’s not for kids.”

“But, there’s a clown on the cover.”

Finally, I read a title we couldn’t resist, “Sneaky Snake”. It was on a Ray Stevens album and we just knew we had to hear it. My parents discussed it over dinner.

When the package arrived from RCA, we were so excited. We opened it up, and pulled out a few tapes we couldn’t care less about, the Moody Blues, Chet Atkins, Herb Alpert, and there was Ray Stevens looking up at us. We begged to put it on and sat down to be amazed.

We laughed, and danced, but about three tracks in, with no explanation, my mother hit the little round silver button, popped the tape out, slipped it back in its cardboard protective sleeve and slipped it into the prepaid envelope.

“Why?”

“Well, it’s not appropriate for children,” she said.

We cried. I think my attitude got me sent to my room that day. I remember yelling about it not being fair, and something about my property and how she didn’t have the rights. But, upon further reflection, I’ve realized, many of Ray’s songs weren’t really written for kids. Even though we didn’t understand the adult humor, my mother felt the need to protect us from it.

That night, my dad played a concert for us, in the living room of the “Whitney Mansion” the house we lived in, that belonged to the congregation he preached for. It had belonged to the first banker in the tiny town of Atlantic Iowa. He stood in the center of our living room, under a custom, pewter, hanging lamp, with pressed butterflies encased in stained glass panels.

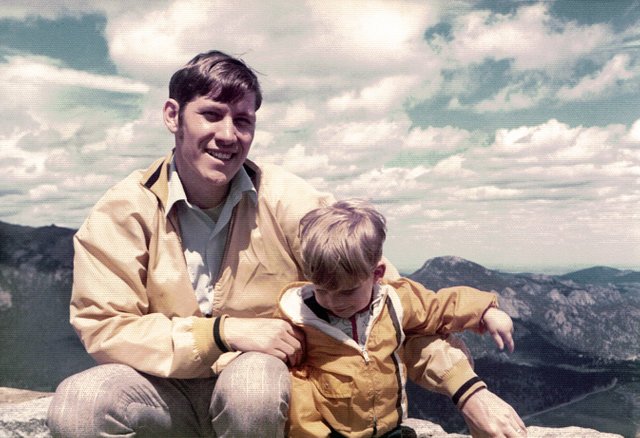

Against a backdrop of leaded glass windows, the butterfly chandelier cast diamonds of light and dancing butterflies across the mahogany paneled book cases and gray silk wall paper as he sang his songs. I remember his brown leather boot toe bouncing in time in the red shag carpet. He sang about mountains and eagles, and forests that I could only imagine at that point, but later would come to love as much as he did.

“No Iron Horse that runs on a track could make Old Black back down….

Talk is cheap and the day won’t keep,

Better start covering ground boys, better start covering ground.”

As he played and sang, he told stories about trains racing horses and magic and fairytales. Then, he’d sing “Jan’s Song” about the time my parents fell in love, and he’d smile at her, his big voice filling the room, the guitar chords echoing from the vaulted ceiling and she would sit, with tears in her eyes and the biggest smile I could possibly imagine.

He sang with a passion that I knew I wanted. It was the same when he preached. He was happy. The smile, which was a hallmark of his existence, was exuberant and genuine. He was confident, but humble. I loved to watch him do almost anything.

What I didn’t know then, but have grown to accept in the process of raising eight kids is this, being a dad is a lot like writing a song, or building something, or writing this book. You make it up as you go along. It’s true. Even after almost a combined million hours of parenting over the last two decades, there are times I still don’t know what to do, so I do the best I can with what I’ve got.

We don’t tell anyone this. I’m going to. I’m going to share it with my four sons. They need to know. My dad was a good man, but virtually incapable of admitting when he was wrong. Maybe he didn’t realize it, that he was making it up as he went along, just whistling through life, strumming along, sometimes he’d remember what he’d played the last time, sometimes he’d start over, writing down bits of it to be used again when the opportunity presented itself.

I wish I’d known all of this when I was ten, or God help me, fourteen, and thought I could see so much clearer than he did. I’m sorry dad. I didn’t know you were making things up. I thought you saw how unfair some of it was and did it anyway. I thought you knew what you were doing and I blamed you for a lot of it. But, you know that now.

To be honest, coming from a man whose only experience with having a father of his own was less than inspiring, it’s amazing he even tried. Many, with better examples, don’t. They just don’t. They look at the long list of priorities that will always come before anything they want for themselves and they check out. Sure, they may hold a job and pay the bills, but their children grow up never knowing them. I knew my dad and I am a better man for it.

We sat in my baby sister’s living room the other day, my siblings and our spouses and our kids, and my dad’s widow, Angel. We sat and we remembered him and I tried to play my guitar, something I’d like to get better at, in his memory. I played what I could remember of his songs and thought about how sad it is that my memory is the only place some of those things even exist anymore and why should that be?

Why should one poet’s words be enshrined for thousands of years, while another’s vanish, like the echo of some unimportant door closing, down a long hall no one visits anymore? Were his ideas not worthwhile? They must have been, they’ve inspired literally thousands of people, which is something.

That’s a new idea for me, that the man was a poet, and that means a lot to me. I’ve spent my adult life pursuing a living from the arts, as a theatrical director, writer and performer. I wish I could have truly recognized the poet in him, but just like great artists, sometimes we just can’t see the brilliance of their work until they’re out of the way and we take it for what it’s worth.

Harmony