The Inspiration Behind Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (Part - 1)

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, born about 80 BC He served under Caesar in the Roman army and specialized in the construction and development of artillery machines. His assignments took him to Spain today and to France and North Africa. Vitruvius then became an architect and worked in a deceased temple in the Italian city of Fano. His most important work was the literary, the only surviving book on ancient architecture: De Architectura, now known as The Ten Books on Architecture.

For many dark centuries, Vitruvius 'work remained forgotten, but in the 1400s it was one of the many classical works, including Lucretius' epic poem on the nature of things, and Cicero's words, the rediscovered collection the Italian pioneer and they were. Humanist Poggio Bracciolini. In a convent in Switzerland, Poggio found a copy of the work of Vitruvius of the eighth century and sent it to Florence. There it became part of the firmament of the rediscovered classics that established the Renaissance. Brunelleschi used it as a reference when he traveled to Rome when he was young to study and study the ruins of traditional buildings, and Alberti quoted extensively in his treatise on architecture. One of the new printers in Italy published a Latin edition in the late 1480s, and Leonardo wrote in a notebook: "Ask the stationery about Vitruvius."

What work Vitruvio called Leonardo, was that analogy was made, which goes back to Plato and the old and had become a defining metaphor for Renaissance humanism: the relationship between the microcosm of the human being and the macrocosm of the earth.

Leonardo took the analogy both in his art and in his science. He wrote at this time: "The ancients called the man a lesser world, and certainly the use of that name does well given because his body is analogous to the world."

With this analogy in the design of temples, Vitruvio stipulated that the plan should reflect the proportions of a human body as if the body is placed flat on its back in the geometric shapes of the plant. "The design of a church depends on symmetry," he wrote at the beginning of his third book. "There must be an exact relationship between its components, as in the case of a well-formed man."

Vitruvius described in great detail the proportions of this "well-formed man" who was going to design a temple. It did assumed that the distance from his chin to the top of his forehead was one-tenth of his full height, he began, continuing with many other similar notes. "The length of the foot is one-sixth of the height of the body, the forearm, the fourth, and the width of the chest is also a quarter The other members have their balanced proportions, and its use has the famous painter and sculptor of antiquity He won a great and endless fame. "

Vitruvius's descriptions of human proportions would inspire Leonardo as part of the anatomy studies that had just begun in 1489 to compile a similar set of measurements. More generally, Vitruvius believed that the proportions of man to those of a well-designed temple - and the macrocosm of the world are analogous - central to Leonardo's worldview.

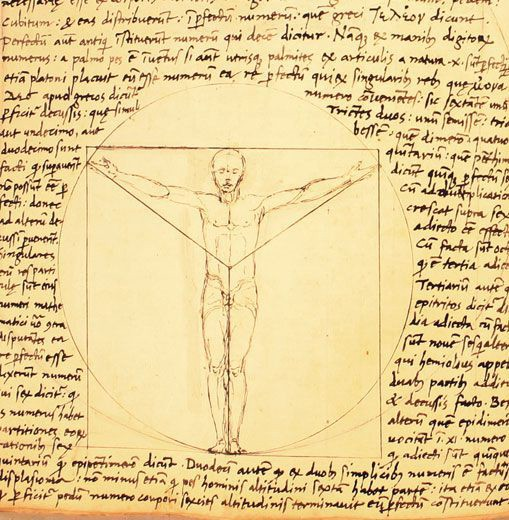

After detailing the human proportions, Vitruvius went on to describe in a great visualization a way to put a man in a circle and a square to determine the ideal relationship of a church:

In a temple, harmony must reign in the symmetrical relationships of the various parts of the whole. In the human body, that central point is the navel. When a man lies on his back with his hands and feet extended and a compass centered around his navel, his fingers and toes touch the circumference he describes. And just as the human body provides a circular contour, a square can also be discovered. If it is us to say, until the tip of the head to measure the distance of the feet and then apply this measure to the extended arms, the width to the height, as in a perfect square, which is found. ..

It was a high image. But, as far as we know, none of us, in the fifteen centuries since Vitruvius had written his description, had made a serious and precise drawing in that direction. Then, around 1490, Leonardo and his friends set out to address this representation of the Eagle Man Spread in the midst of a church and the universe.

Francesco di Giorgio produced at least three of these drawings, which were designed to accompany his treatise and translation of Vitruvius. One of them shows a sweet and dreamy image of a man in a circle and a square. It is more a suggestive drawing than a precise picture. The ring, the square, and the body do not try to show the proportions but last represented casually. Two other paintings by Francesco show a man carefully proportioned in a circular and square pattern in the form of a church plan.

Giacomo Andrea

Almost at the same time, another dear friend Leonardo made a drawing of the text of Vitruvius. Giacomo Andrea was part of the collaboration circle of architects and engineers gathered by Ludovico at the Milan court. Luca Pacioli, a mathematician and another close friend of Leonardo, wrote a dedication to an edition of his book on the perfect relationship he presented to the distinguished members of that court. Pacioli added: "There was also Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara, who was as dear to Leonardo as his brother, an avid disciple of Vitruvius' works."

Andrea produced a simple version of a man with a full mouth in a circle and a square. Surprisingly, the circle and the square are not centered; the circle rises higher than the square so that the man's navel can be in the center of the ring, and his genitals are in the middle of the square, as Vitruvius suggests. The arms of man are extended, Christ is like, and his feet are very close together.

Finally, the French troops killed Andrea and brutally butchered her when they conquered Milan nine years later. Soon after, Leonardo would search and find his manuscript copy of Vitruvius' work. "The knife Vincenzio Aliprando, who lives near the inn, has the Vitruvius of Giacomo Andrea," he explains in a notebook.

Andrea's drawing was rediscovered in the 1980s by architectural historian Claudio Sgarbi found a highly illustrated manuscript of Vitruvius's book, which has languished in archives in Ferrara, Italy. He discovered that Andrea had put together this document. Among his 127 illustrations, Andrea was the Vitruvian Man's version.