Understanding Civil Lawsuits in the U.S., a Steemit Exclusive

Earlier in my life, I was a licensed attorney in California. I no longer trust the legal system the way I once did; it is badly broken. But I'd like to share this guide for anyone who gets sued or needs to bring a lawsuit. If you have a good sense of the legal process and what it involves, you can keep your lawyer honest, save yourself money, and have a better chance of winning.

Understanding Civil Lawsuits in the U.S., a Steemit Exclusive

By Richard Kaplan

Contents of this guide are free for you to use, with attribution:

Please include a prominent link to this post on Steemit

Contents

- Civil Law in the United States

- Preparing, Filing, and Responding to Lawsuits

- Class Actions

- Pretrial Discovery

- Common Motions Filed by Both Sides

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

- Settlements

- Evidence and What Can Be Used in Court

- The Trial

- Appeals

Disclaimer: This guide and its contents do not constitute legal advice, nor is any attorney-client relationship formed between the author and readers. If you need legal assistance, please seek the services of a qualified attorney licensed to practice in your state or country.

Introduction and Confession

Earlier in my life, I was a licensed attorney in California. I no longer trust the legal system the way I once did. The system is badly broken. We basically have two kinds of justice now, one for really rich people and one for everyone else. It is unconscionable for lawyers to charge such high fees to people who need legal help.

If you are sued or charged with a crime, then you really do need a lawyer. As Abraham Lincoln said, “He who represents himself has a fool for a client.” But there is a way to save money and gain a lot more power in your relationship with your attorney. If you have a good sense of the legal process and what it involves, you can keep your lawyer honest. He (or she) won’t rip you off as much and he may dedicate more energy to your case. Unless your lawyer is a saint, you should read this guide: you’ll spend less money and probably improve your chances of winning.

I used to teach a law class at the local college. Frustrated with mainstream textbooks, I wrote my own guide for students on how to understand the process of lawsuits (particularly civil lawsuits, since that was my expertise). Aside from some students who still use this, Steemit users are the only ones with access to this guide. It isn’t published elsewhere, so we’ll call it an “exclusive”. I am posting it here for free and hope you can use it.

Chapter 1: Civil Law in the United States

Most of the time, civil law is about money. While criminal law involves a wrong to society and the defendant’s punishment for hurting a victim, civil law involves a different kind of injury. In a typical civil lawsuit, a plaintiff claims to have faced personal injury, property damage, or economic hardship. If the court determines this injury resulted from the defendant’s wrongful actions, then the plaintiff will win. Money.

As a former attorney, I am experienced with lawsuits. I have seen a woman who couldn’t walk without pain because she was struck by a car that malfunctioned. That woman won a settlement worth millions of dollars. She was glad to receive some justice for the defendant’s offense, but she never felt like she’d won the lottery. That woman would have given back the money in a heartbeat if it meant she could walk well again.

Some things are more important than money, and money will not solve all our problems. But money is our currency of value. Therefore, civil law values injuries or losses in monetary terms. These are called damages.

When that plaintiff lost her ability to walk, what was the value of that injury? In the short term, she lost time at work, she had to pay for medical treatment and a new wheelchair, her car was totaled, and she experienced mental trauma. And in the long term, she will continue to suffer from her injury and it will continue to cost her financially for the rest of her life. Our legal system asks us to add up all the costs (including future projected costs) and come up with a price.

Once the defendant has paid this compensation to the plaintiff, our legal system concludes that she has been returned to her original, whole position. This may not happen physically, but financial balance has been restored. Winning a lawsuit is not about winning the lottery or gaining a financial windfall. Civil law aims to compensate the victim and return things, as well as possible, to where they were before the injury occurred.

When the United States was founded, our Constitution established the rule of law and provided the basis for our court system. Since the U.S. had been a British colony, we inherited the system of common law that had existed in Britain. When courts decide cases, these decisions become part of the legal fabric in this country. Past court decision are known as precedent. When these precedents are added together, they become the common law.

Much of civil law, including the law of property, contracts, and personal injury, has been developed in courts through the common law system. This means that the rules are not necessarily written down in some code book created by Congress or your state legislature. They may be there, but they are more likely to exist in case law. Judges look to past decisions to determine how they should interpret the common law and rule on legal issues that come up during the case.

Note: It’s important to be gender-neutral, but I also need to make the reader’s job as easy as possible. Therefore, I will use the pronoun “he” to refer to a nameless party, such as the plaintiff or the defendant. This use of “he” really means “he, she, or it” (since corporations and other organizations can be parties, too).

Chapter 2: Preparing, Filing, and Responding to Lawsuits

The process of a case is known as litigation process begins when a client enters a law office and engages the services of an attorney. This attorney agrees to represent the plaintiff in the upcoming case. If a potential defendant believes he is likely to be sued, he may proactively consult a lawyer also.

While it is possible to represent yourself in litigation, I do not recommend this if you have a lot riding on the outcome. In a high stakes battle, you need a good advocate who knows the ins and outs of your local court system. If there is less at stake and you can handle the possibility of losing, then you may choose to represent yourself and save the money it would cost to hire a lawyer. Either way, the information in this guide should help demystify the litigation process and enable you to make informed decisions at each stage of the game.

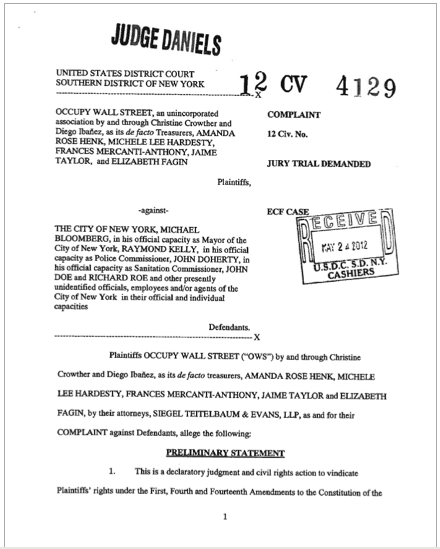

The plaintiff formally declares war on the defendant by filing the case in court. This filing is known as the complaint and it the first of several possible court filings during the pleadings stage. The complaint begins by introducing the parties and assuring the court that it has the proper power to hear this kind of lawsuit involving these particular parties. The complaint then explains the reasons why the plaintiff is seeking the court’s help. It alleges facts that, if proven true, entitle the plaintiff to a court judgment in his favor. The complaint ends with a demand for relief, which spells out the damages that are owed to compensate for the plaintiff’s injuries or losses.

Under federal and state rules, court complaints must contain a short and plain statement of the facts that form the basis of the lawsuit. These facts are tied to at least one recognized legal claim, such as negligence, assault, or breach of contract. At the pleadings stage, evidence and proof are not yet required. Defendants usually try to get cases dismissed or decided early on. If the plaintiff’s allegations are strong enough, the case will move forward, but if they are weak, then the judge may dismiss the case.

The complaint, like other pleadings documents, must be filed with the court that has power to hear this case. Most of the time, this will be a local county court, which is the trial court unit of a state’s court system. When a federal law is involved or when the matter involves residents of different states and more than $75,000 is at stake, then the case can be brought in federal court. Filing is normally done in person at the court, though most courts are moving towards electronic filing and this is available in some locations, for certain types of cases.

Here is a picture of many boxes of documents being loaded. Believe it or not, all of them are involved in a single case. You can see why everyone wants to see more e-filing and electronic document sharing. Finding something is as simple as a key word search rather than a digging adventure that can consume many wasteful hours of peoples’ time.

Below is a copy of the first page of a complaint. I know it’s a little blurry, but you don’t need to read much of it. I just want you to see the basic format.

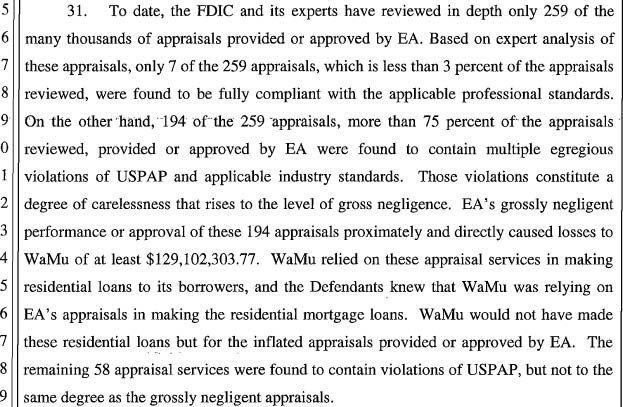

And here is another example of a complaint in a different case. This one shows a paragraph that contains some of the plaintiff’s allegations. As you can see, these are based on the facts of what happened yet they are presented in a way that alleges violation of a civil law. Here, that civil law is gross negligence, and the plaintiff here is fitting the factual allegations to the definition of this law.

In the past, all complaints were written from scratch and every one of them was unique. A few years ago, in an effort to simplify their jobs, courts began to introduce forms that could be used to draft the complaint and other pleadings. Other courts accept e-filing through a number of software programs, most of which generate something like a PDF document on the court’s end. Keeping things simple saves time and money for the courts. In another generation, robots may be doing this work for us.

Some state courts even require these forms now because they are so much quicker to prepare and to read. Basically, the forms have places where you can write in the names of the parties, check some boxes for which type of case it is and how much money is being sought, and then write a few paragraphs on the factual allegations and legal claims. Some lawyers still prefer to write out pleadings documents.

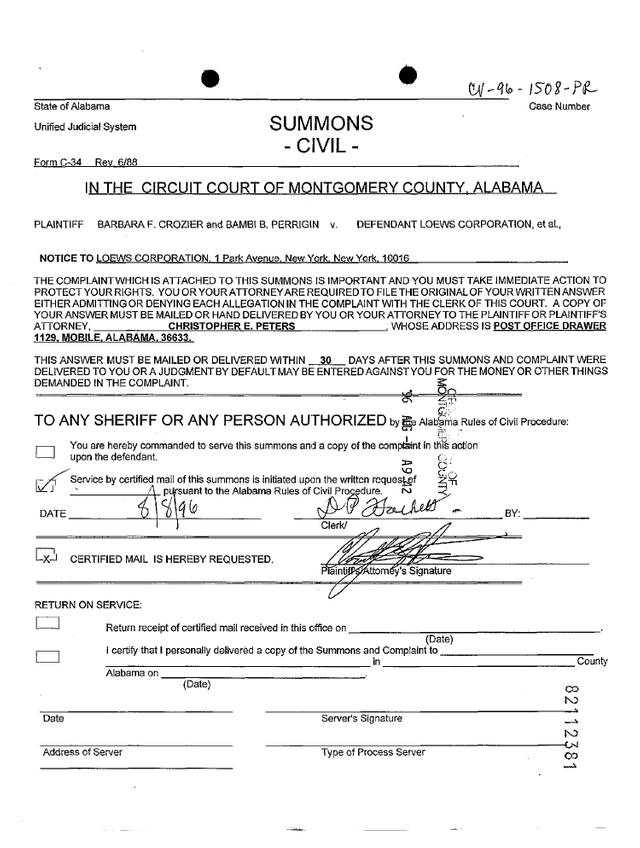

The defendant gets the bad news when he or she is served with process. The defendant receives two things: a copy of the complaint filed by the plaintiff and a summons from the court. Most states allow this notice of the lawsuit to be served either in person or by certified mail. Many law firms use electronic service as well.

Here is a copy of a summons used by a civil court.

The summons, which bears the signature or stamp of the court clerk, notifies the defendant he is being sued. Under the power of the court, it requires the defendant to respond to the plaintiff’s allegations. The defendant is given a certain period of time, usually 20-30 days (depending on the court and filing method) in which to file a response.

Filing a motion to dismiss the case may buy a little more time, but the clock will continue to tick if the judge denies this motion. The summons also warns that the defendant can lose the case automatically if he fails to respond. If no response is received by the end of this period, the court will record a default judgment in the plaintiff’s favor.

The defendant’s responsive pleading is called the answer. Under the rules of civil procedure, the defendant must use the answer to admit or deny each of the allegations made by the plaintiff in the complaint. If the defendant lacks enough information to admit or deny an allegation, then he can state this lack of information as an excuse for not admitting or denying something. But playing this card too often will upset a judge.

Also, the defendant must use the answer to make any additional arguments. In the language of law, these arguments are known as defenses (short for “defensive arguments”). If a defendant does not mention a possible defense in the answer, then he cannot raise that argument at any time later in the case. This rule forces him to consider all possibilities now, including even arguments that may not be needed (or that may turn out to be baseless) later on. Better safe than sorry.

For example, imagine a defendant is being sued for committing battery. In civil law, a plaintiff can win a battery claim if he can show that the defendant intentionally made harmful or offensive contact with his body, without his consent, causing some injury, damage, harm, or loss to the plaintiff. The plaintiff’s complaint states that the two were involved in a neighborhood game of touch football. During this game, an argument allegedly ensued and the defendant allegedly hit the plaintiff hard in the face. As a result of his injuries from this blow, the plaintiff required extensive medical care, reconstructive surgery, and psychological treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

We don’t know what really happened, but let’s imagine what arguments the defendant might possibly make. There are at least two good possibilities. First, the defendant could deny that this fight took place or that he struck the plaintiff in the face. If he even denied that the contact was intentional (and if he could show it was accidental), that would knock out the required “intent” element of this claim.

Second, he could admit he hit the plaintiff in the course of their game and then raise a separate defense to justify this action. One such defense could be that football is a dangerous and violent sport. The plaintiff knew or should have known that football players often get hit during the course of a game. Since the plaintiff voluntarily assumed the risk of injury by agreeing to play, the defendant would argue that he cannot be held liable. Assumption of the risk is a recognized legal defense to battery, and this fact might knock out the “lack of consent” element of battery anyway.

A second such defensive argument might be self defense. You probably are familiar with this argument from all those movies and TV shows. “He was hitting me and I acted to protect myself. Therefore, I am not legally at fault for hurting him” (or killing him, since this defense is used against murder charges also!).

The actual arguments would depend upon the facts of the case, but these examples give you an idea of how defenses work. Again, these arguments must be raised in the answer which the defendant files in court. If they are not included, he cannot use them later in the case.

In a complex case, there may be more pleadings filed than just the complaint and answer. The defendant is welcome to include a counterclaim with his answer. This means that he turns around and sues the plaintiff. He generally does not have to pay a filing fee for this, so the counterclaim is a free shot, but any claim he makes must be supported by the facts.

It can be difficult to illustrate the litigation process in a visual way. But here is visual proof that a good counterpunch can keep your opponent off balance. Make them think you’re psycho and they’ll think twice about messing with you!

If the defendant believes that someone else (other than him) is responsible for the wrongdoing, then he can join that third party as a defendant to the case. This can happen, for example, if a building contractor claims that a subcontractor or an equipment manufacturer was the one responsible for a building defect.

If there are multiple plaintiffs or multiple defendants, then they can sue one another also. When one party sues another party who is on the same side (plaintiff versus co-plaintiff or defendant versus co-defendant), this is known as a cross-claim. There are more of these pleadings possibilities, also, but it starts to get pretty technical. Basically, anyone who wants to file a claim against someone else can do so if the claim involves the same case.

Chapter 3: Class Actions

Some lawsuits can get very complex. When most of us think of a court case, we imagine one plaintiff and one defendant. But quite often, cases feature more than one party on each side. For example, consider a case where a car allegedly malfunctioned. The plaintiff claims that a defective part broke and this caused the car to spin out of control, giving rise to an accident that resulted in personal injuries and property damage.

Who is the logical defendant? The car maker would be enemy # 1. But of course there is at least one layer of insurance, plus the seller of the car, such as a dealership. And the car maker may argue that the allegedly defective part was manufactured by a subcontractor based on the design of another company. The subcontractor may argue that the part was not defective, but it was re-installed incorrectly the last time the car was serviced at an oil change place. Okay, so that already brings us up to at least six defendants, which is not unusual in many cases.

The same thing can happen on the plaintiff’s side of a case. Some defendant’s act or negligent oversight can affect a lot of people. Imagine a large group of apartments which were all built by one construction company. Five years later, 39 of the 86 tenants in the apartment complex are suffering from rashes, headaches, and other health symptoms. It turns out that the construction company used cheap, substandard sheetrock which absorbed more moisture than usual from the air and became a perfect home for mildew and toxic black mold. Now, five years later, mold was infesting everyone’s apartments, causing health problems, and they just could not get rid of it.

This case still has the potential for multiple defendants. Like the car example above, this case is likely to involve insurers, subcontractors, sellers, and others who participated in the chain of design, construction and distribution. But it’s also different than the car case because there are more plaintiffs: 39 of them, all with basically the same facts to report in their complaint. And what if this same construction company ordered and installed the sheetrock for six other large apartment complexes around that same time, where other cases of mildew exposure are being reported also? We are talking about hundreds of potential plaintiffs.

A class action suit is one where a named plaintiff, or a handful of plaintiffs, decide to pursue the case on behalf of a larger group. Some of these group members may be knowledgeable about the case and support it, while other potential class members may not have been identified yet and do not know someone is asserting their rights in court. An effort will be made to find everyone affected and if the plaintiffs should win the case or settle, and then there will still be a window of time during which additional class members can identify themselves, prove that they belong, and share in the award.

To become a class action suit, the case must meet certain requirements (such as all plaintiffs’ claims deriving from the same set of circumstances) and the group of plaintiffs must be certified as a class by a judge. The typical minimum size for a class is 100 plaintiffs. It may be possible to maintain a case with a smaller class, but 100 is the minimum number required by some state and federal laws that are used by plaintiffs to bring such cases. If similar cases are filed in different courts, or in both state and federal courts, then it is likely that the various claims will be consolidated into one case in one court. A 2005 law made it more likely that these claims could be consolidated and brought in one federal district court.

While class action cases need to be litigated like any other civil case, most end up settling without trial. Defendants are fearful that a jury will not be too kind to them when they hear all the sob stories and see the gruesome pictures of peoples’ health problems. Defendants usually settle.

A settlement fund is set up to be controlled by an administrator under the court’s oversight. Class action cases can go on for many years, not because of the legal issues and the trial (if there is one), but because of the complexity of administering the settlement, tracking down all the class members, and evaluating their claims to make sure they are eligible to participate. A handful of courts around the country, and a handful of law firms, have developed an expertise in class action cases. There are others who prefer not to handle this kind of complex litigation, happy enough to transfer it to another court or leave it for another law firm.

Chapter 4: Pretrial Discovery

If you’re old enough, you might remember a TV lawyer named Perry Mason. The show was filmed in black and white, starring Raymond Burr in the lead role. Perry Mason was famous for putting a surprise witness on the stand or uncovering a piece of slam dunk evidence. He won most of his trials with last minute drama.

Today, there very few bombshells during trials. No more secret witnesses and last minute smoking guns. Under the modern rules, a party must disclose most of the case to the other side before trial. The pretrial process is so drawn out that by the time trial finally rolls around (if the parties don’t settle first), there are no surprises left to uncover.

Once the defendant has filed his complaint, the pretrial process called Discovery begins. Discovery is the process of investigating, interviewing witnesses, and assembling evidence. While you are building your case, the rules of civil procedure allow you to learn a great deal about the other side’s case as well.

The more everyone knows before trial, the more likely they will settle the case. If the parties know what to expect at trial, they can estimate the likelihood of winning or losing. They can put a dollar figure on what the case might cost them. This process is designed to encourage out of court settlements and prevent most cases from ever coming to trial.

Trials are expensive, time-consuming, and risky. Settlements provide certainty, finality, and can be kept confidential with no need for the defendant to admit liability. A defendant may even spend less on a settlement than he would spend taking the case to trial.

The court system is very costly to operate and maintain. The taxpayers pay for most of it. Both federal and state courts in this country are overloaded with cases and strapped for cash. They do not have the capacity to handle many additional trials.

So everyone involved, from the people who wrote the rules of procedure to the judge who is assigned to your case, will encourage you to settle before trial. Sometimes it seems like they’re trying to put themselves out of business, but in fact, they have plenty of work to keep them busy.

Most courts encourage, and some even require, a settlement conference before trial is scheduled to begin. In federal courts, some 98 percent of all cases are settled and never reach a trial verdict. In state courts, the figure is somewhat lower, but still more than 90 percent of cases are resolved out of court.

The pretrial Discovery stage provides parties with plenty of tools to develop their cases. These tools include Interrogatories, Requests for Admission, Depositions, Document Production and Inspection Requests, and Medical Examinations (these terms will be defined and explained below). Each party must comply with the other side’s requests for information when these are made using the Discovery tools.

If a party does not play fair, then his opponent can go to the judge and request a court order to force him to comply with the rules. The judge has the power to order sanctions against a party or his attorney for failure to comply. These sanctions can include monetary fines or dismissal of the case. The judge also has the power to hold a party in contempt of court, which is backed by the threat of possible jail time.

Interrogatories

Interrogatories are written questions that each side can prepare and serve on the opposing party. The other party must respond to the questions within a certain period of time, providing the information that is requested. There is a limited number of interrogatory questions that each party can ask, usually 25-35 questions, depending on which state or court is involved.

Many lawyers use interrogatories to locate evidence or witnesses to help them build their case.

Friendly witnesses can be interviewed voluntarily, but the opposing party’s witnesses will not be as cooperative. In order to learn what they can add to the case, an attorney needs to order these witnesses to attend a deposition.

Most attorneys like to reserve a few interrogatory questions to ask later, so they do not ask the full number they are allotted in just one set. Interrogatories are useful at an early stage in the case, but some can be reserved for later when the parties learn more about the case and need to follow up on new information. Therefore, we often see defendants’ being served with “Plaintiff’s First Set of Interrogatories” which contains fewer than the maximum number of questions. If the court’s limit is 25 interrogatories, for example, then the First Set might include just 10-20 questions, reserving the rest for a Second (and maybe even a Third) Set.

Under the rules, a party receiving a set of interrogatories must respond to them within a set time frame (usually 30 days). In writing and under oath, the party must provide a separate answer to each interrogatory question. However, the party also can object to a question by explaining the specific grounds for that objection. Objections here are frequent (for example, that a question is argumentative, too general, or requesting information that is privileged). If a party does not object, that argument is considered to be waived, so this is the time to raise it.

But even if a party objects to a question, most requests are answered anyway. No one wants to have to explain to the judge why he objected to every question and provided no real information in response to the interrogatories. Because this is discovery, an angry judge could issue a discovery (court) order and threaten a non-complying party with sanctions. Therefore, as you might have guessed, writing good interrogatory responses and objections is an art form.

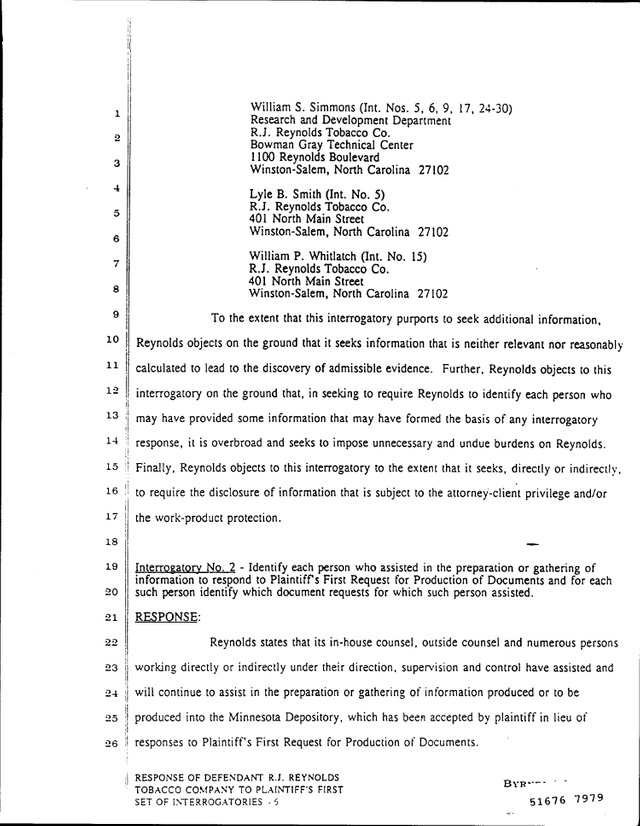

This image is taken from a tobacco case. It shows a page from a defendant’s response to plaintiff’s interrogatories. You can see how an objection is written, and from line 19 on down, you can see an interrogatory question and the beginning of this defendant’s response.

Requests for Admission

Requests for Admission are very similar to interrogatories, but are used differently. Under the rules of procedure, a party can provide a list of statements to the opposing side which that party must admit, deny, or fail to answer by explaining the specific reason for this failure to respond (most commonly, this is due to a lack of information or knowledge). These are most often used to establish facts in the case that are not in dispute (for example, that the accident occurred on the morning of December 31st or that defendant was driving a red Jeep Grand Cherokee). If there’s no real dispute about some facts, then no one wants to waste time having to prove them at trial. Requests for Admission help enable that kind of agreement between the parties.

Depositions

A deposition is a live, out of court questioning session. It normally takes place at an attorney’s law office. Though the judge does not attend, a court reporter (and often a videographer also) is present, the witness is sworn in, and the deposition becomes part of the official court record of the case. The opposing party’s attorney will be there also to make sure the questioning stays fair and relevant to the case.

Normally, the deponent (person being deposed) will be asked to bring along any relevant evidence, such as documents in his control. He will be asked about his role in the subject matter of the case. His attorney may object to certain questions and instruct him not to answer if the questions request information that is inappropriate (such as hearsay, which usually cannot be used in court). Because the deponent is under oath, everyone expects that his answers in the deposition will be the same when he is called as a witness at trial. If a later in court statement is different from what he said in the deposition, then a video or copy of the court reporter’s transcript can be introduced to point out this inconsistency.

A deposition may only last an hour or two, but an attorney will take as much time as he or she needs to get the complete information. Some attorneys ask the same question many different ways. Others try to bore, distract, challenge, anger, or wear down opposing witnesses. In complex cases, an important deposition can take days.

Document Production and Inspection Requests

Also as part of the Discovery phase, a party is allowed to serve a request upon an opponent to inspect, copy, test, or sample items within that opponent’s control. Most often, this power is used to obtain documents or electronic files that are within the custody of the other party. Once served with the request, the party holding the documents or files must either provide copies or allow the requesting party to view and copy them at a certain place and time. Production requests can be used for other types of items or to allow an inspection of land or facilities (including measuring, surveying, photographing, testing, or sampling) as well.

In civil cases, many defendants are entities such as large corporations. Plaintiffs who are suing them usually do not have access to the same amounts of money. Therefore, a common strategy for a large defendant is to exhaust the plaintiff and his resources. If the defendant can increase the number of hours the plaintiff’s legal team must spend on the case, then the cost of the lawsuit shoots up. At some point, the plaintiff may either give up or be forced to accept a small settlement.

One common way to pressure a plaintiff is to bury him in paperwork. When the plaintiff serves a document production request that is fairly general, such as “Please produce copies of all documents that evidence or refer to defendant’s hiring policies in effect in 2012,” the defendant sends over copies of everything remotely related to this. The plaintiff’s legal team might get 10 times or 100 the number of documents they expected. Now they must put attorneys, paralegals, and other paid staff members on the task of sorting through boxes and boxes of information that might or might not be relevant. This drives up the cost of their suit very quickly and prevents them from conducting more meaningful investigations during this time.

It is difficult to write a good production request when one does not know exactly what documents exist. This is another reason to begin discovery with interrogatories, which can reveal the existence of certain documents which the requesting party can then obtain though production. Good attorneys can word their document production requests very skillfully so as not to be too specific (perhaps missing something important) or too general (a request to get inundated with paperwork). As more and more records are kept electronically, and these can be searched more quickly and easily, the document inundation problem will continue to fade. No doubt it will be replaced by newer problems.

Medical Examinations

When a party’s physical status in central to the case (such as a plaintiff who was injured in a car wreck and is suing on that basis), the opposing party can require a medical examination. This can be an independent, third part examination conducted by a physician who is not associated with either party. The results can then be made available to the party requesting the exam. In the less likely event that a party’s mental state is in question, the rules also allow for the opposing party to request a mental examination as part of discovery.

The Importance of Discovery

Now you can see why most civil cases settle. The modern rules require so much sharing of information that there are few, if any, surprises left for trial. After all this information gathering and sharing, a party can fairly gauge its odds of winning at trial and estimate the cost of paying compensatory damages. The days of last-minute surprises at trial are gone. As a result, Discovery is the most important stage for most cases.

Chapter 5: Common Motions Filed by Both Sides

Throughout the course of a case, many motions will be filed by the parties. The majority of these will be filed before trial, but some will be filed during trial. There are many possible motions, but here are a few of the most common ones in a typical case.

Motion to Dismiss (Demurrer)

The Motion to Dismiss (known as a Demurrer in some courts) is the first motion that is filed in most cases. Understandably, defendants do not want cases to continue any longer than they must. So if there is a chance of getting a case thrown out right away, a defendant will take it. When evaluating a Motion to Dismiss, a judge will look only at the plaintiff’s complaint, assuming (for the purposes of ruling on this motion) that all facts contained in the complaint are true.

The party requesting dismissal must have some specific reason to cite for this. Often, the defendant asks the court to throw out the case for procedural reasons. Examples of this are as improper service, failure to join a party who is essential to the case, or an argument that the court does not have the authority (jurisdiction) to hear this type of case.

Also, it is common for a defendant to allege that the plaintiff has failed to state a claim. This argument can succeed if the plaintiff has not shown how the law requires a court to enforce the right or responsibility that is at the core of the case. This may be based on a different reading of the law or because the law says something that bars the plaintiff from winning this case. For example, if the defendant did something wrong but the plaintiff did not suffer any injury, a particular law may not allow him to bring such a suit. Or the statute of limitations on a particular claim may have passed.

When a case is dismissed, the dismissal can be made either with prejudice or without prejudice. When a case is dismissed without prejudice, this gives the plaintiff an opportunity to correct some error and then file the case again. Dismissal without prejudice is a final order from the court that ends the lawsuit. This means that the same case cannot be filed again. A plaintiff whose case is dismissed with prejudice can appeal this decision.

Motion for Summary Judgment

Motions for Summary Judgment are used in most cases also. Either side (or both) can file a Motion for Summary Judgment during Discovery or shortly afterwards. By requesting Summary Judgment, a party is not just asking the judge to throw out the case. He is asking the judge to make a final legal judgment in the case.

A judge can grant Summary Judgment to a party (a final judgment in his favor) only if there are no factual issues remaining for trial. By this point in the case, the judge will have all the evidence available that has been collected by the parties during Discovery. A Motion for Summary Judgment will cite to all of this evidence in the case record, including interrogatory responses, deposition transcripts, document productions, witness interviews, and the pleadings themselves.

If, after examining that evidence, the judge agrees with the filing party that the evidence is so one-sided that there is no dispute of material fact remaining, then the judge is required as a matter of law to decide the case in that party’s favor. The case is decided without it ever going through trial or to a jury. Such a result is possible only because the judge is making a ruling of law (the judge’s job), not of fact (which is the job of the jury). We will cover these roles more thoroughly in the chapter on trials.

Motion in Limine

A Motion in Limine asks the court to limit the use of certain evidence. This is more common in criminal prosecutions, but is used in many civil trials as well. The most common example of a Motion in Limine is in a drug prosecution case. The defendant will argue that the police did not have a warrant to search his house, and since the search was not proper, the drugs they found should not be admitted as evidence.

In a civil case, a motion in limine is often used to try to block the testimony of an expert witness. The party filing the motion can object to this witness’ expert qualifications or argue that the testimony will not be relevant or helpful to the jury in understanding the subject matter. A Motion in Limine is filed at the beginning of trial and may not be decided right away, but a judge must rule on this request before the challenged evidence is introduced at trial. The opposing party usually will file an opposing motion which asks the court to allow the challenged evidence or testimony, providing a legal argument in support of it.

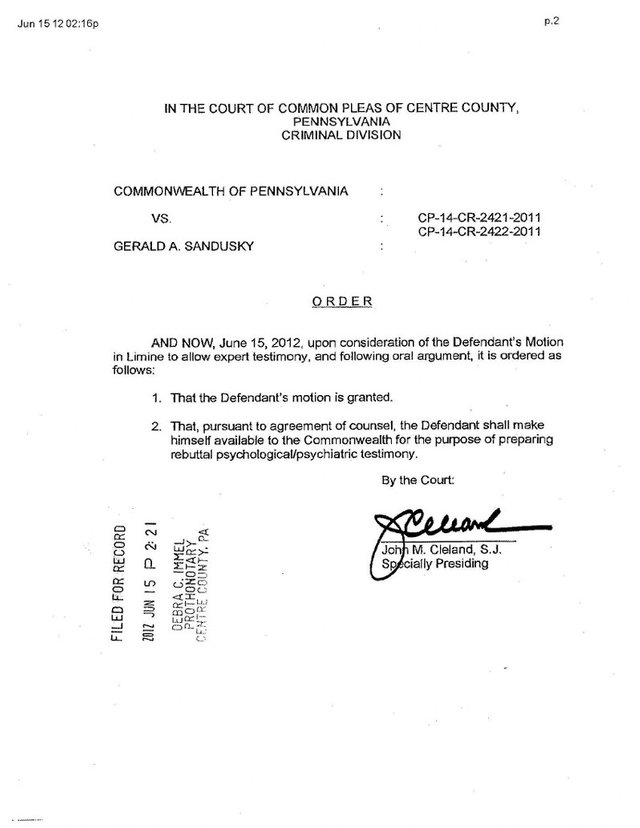

Below is a court order allowing expert witness testimony that was the subject of a Motion in Limine.

Chapter 6: Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

Going to court is not the best way to address all problems. In fact, litigation is a last ditch option when other methods of resolving a dispute have failed. Many court systems not only recommend, but even require, parties to seek some form of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) before bringing their cases in court. ADR consists of several different methods of resolving disputes, including arbitration, mediation, conciliation, negotiation, and hybrid approaches like medarb. Here is an overview of the main ADR methods.

Mediation

Mediation is an informal method of resolution that utilizes a third party, who is known as a mediator. The mediator assists parties in reaching an agreement. The mediator usually meets with both parties in joint discussion and then later meets with them separately to learn about the areas of possible agreement and what sacrifices each one may be willing to make.

The mediator makes a strong effort to help the parties find common ground and chart the path of least resistance in settling the dispute. This agreement may involve some compromise between the parties, but it is voluntary and never imposed upon them. Mediation is quite common in family law, where some courts even require that parties attend mediation sessions before bringing their grievances to the courtroom.

Arbitration

Arbitration is a more formal process. It involves a solution that is imposed on the parties by an arbitrator (often called a neutral). The arbitrator will hear each side’s case, review the evidence, and then make a decision in the matter. The process tends to be quicker, less formal (in terms of evidence rules, etc.), and generally less expensive than going to court. Parties are free to agree on their own rules of evidence and procedure, but most use standard arbitration rules, such as those developed by the American Arbitration Association.

Usually, arbitration is binding in that parties have signed a contract requiring them to honor the outcome. Win or lose, they agree to respect the arbitrator’s decision as final. This means that arbitration decisions are very difficult to appeal in court. A court will only hear a challenge to an arbitration decision if there is some allegation that the process was extremely unfair (which is rare).

Since arbitration saves time and money over going to court, many contracts we sign on a regular basis include choice of law clauses which mandate that any related disputes will be brought to an arbitration panel, not to a court. If you do not believe me about how widespread these are, check the agreement you signed with your cell phone carrier, the one you signed when you bought a baseball game ticket, or just about any other contract developed by a large institution for you to sign. Not all, but most of these, have arbitration provisions nowadays, so you have waived your right to take any related disputes to court.

Conciliation

Conciliation is a process that emphasizes reducing tensions, improving communication, and building trust between parties. As with mediation, a third party professional is brought in to help the parties reach an agreement. Conciliation tends to focus more on compromise than mediation does. It also makes heavy use of private caucus meetings between the conciliator and each of the parties. In fact, with conciliation, it is possible that the parties may never hold face to face negotiations before an agreement is proposed.

Medarb

Medarb is an increasingly popular blend of mediation and arbitration. There are other combinations out there as well. Medarb itself is not a hybrid so much as a two-step combination of mediation and arbitration. First, the parties attend mediation and try to solve their issues informally. Second, if mediation does not produce a successful outcome, then parties move on to arbitration. The arbitration stage results in a decision which the parties have promised (via signed agreement) to respect as the final solution to their dispute.

Negotiation

The process of reaching a settlement by negotiation is widespread in fields ranging from foreign affairs to business. It is widely used in law also. Parties may negotiate directly with one another or through their legal representatives. Negotiations may be handled in a formal or informal manner. Discussions can focus on cooperation or on each side achieving the maximum possible gain for itself. The next chapter will cover settlements in more detail.

Chapter 7: Settlements

A settlement is an agreement, usually negotiated, that brings the case to an end. A settlement even can be reached before a lawsuit is filed if the plaintiff is able to use this pending filing as a bargaining chip. More often, settlements occur later in the litigation process. Many times, a jury has gone off to deliberate and reach its decision in a case only to be called back into court and told the case has settled. Thanks for your time; we didn’t need you after all!

Settlement in a civil case normally involves an agreement for the defendant to pay some money to the plaintiff. In exchange, the plaintiff agrees not to bring a lawsuit over this matter. If the case has been filed already, the plaintiff agrees to drop the case. This settlement may be subject to approval by the judge, which is mostly a formality unless the settlement is illegal or grossly unfair to one party.

There are many reasons to settle a case. First, money is an important consideration. Trials are very expensive. A party must pay for the attorney’s legal fees, court costs, witness fees, and any number of other expenses. Throw in even a small possibility of losing the case and it can make good financial sense to settle.

Second, parties want to limit their liability and exposure to risk. From the plaintiff’s perspective, the best reason to settle is to gain the certainty of walking away with money. It may be less than the plaintiff could have won at trial, but no trial outcome is certain. The defendant’s signature on a settlement agreement provides better certainty. That’s the kind of certainty you can take to the bank. Defendants also want to avoid the risk and uncertainty of a trial. Sometimes, this is worth the cost of paying off the plaintiff to go away.

Third, many defendants prefer the privacy of a settlement over the publicity of a trial, which could end with an adverse verdict that generates negative headlines. Under the terms of most settlement agreements, the defendant does not need to admit liability. In addition, parties agree to keep the terms of the settlement confidential.

The confidential nature of most settlements also has legal value for defendants. It means that other potential plaintiffs will not be able to use this lawsuit as precedent. If the case continued until there was a trial verdict, anyone else who wanted to sue for a similar reason would simply have to look at the public record for a lot of free, case-building material. But when a case ends in a settlement, the terms are not available to the public and cannot be used in other cases.

The majority of all civil cases settle. Therefore, as you might expect of anyone whose living depends on big settlements, attorneys have developed a successful system for these negotiations. First, most negotiations are conducted by the attorneys rather than the parties. Ethically, the attorneys cannot agree to any settlement offer that has not been approved by the client. However, if the attorney knows what outcome the client wants or would settle for, the negotiations can focus on obtaining the desired outcome.

The settlement brochure is another common feature in most settlement negotiations these days. It often takes the form of a video, though it can be a written piece as well. The settlement brochure basically goes through the party’s case, including evidence and witnesses that the party plans to use at trial.

If the settlement brochure presents the plaintiff’s case in a compelling way, the defendant will see how strong the case is and want to settle before trial (or so the theory goes). A high quality settlement brochure might help a plaintiff get some more money out of a defendant who does not want to see a jury enter an even larger damage award.

Studies have shown that many plaintiffs would drop their cases if the defendant simply apologized to them for doing something wrong. Unfortunately, apologies are hard to come by, because they are admissions of liability which can be used by other potential plaintiffs in the future. Most defendants would rather pay off plaintiffs than leave themselves so open to additional lawsuits.

Prior to a civil trial, most courts hold a pretrial conference to schedule the case. This also provides one more opportunity to settle the case. Yes, even the judge would rather the parties settle it out of court than go to trial.

Chapter 8: Evidence and What Can Be Used in Court

A party builds a case by assembling evidence in support of his arguments. This evidence can be introduced at trial to prove his claims. If the case heads toward settlement instead, having the evidence to present a solid case can provide leverage in settlement negotiations.

Forms of Evidence

There are several different kinds of proof that a party can use to build the case. Some cases include all of these types of evidence, while others make heavy use of documents or witnesses. It all depends on the subject matter of the case and what is being argued. Each case is unique and will feature its own sources of proof.

Physical Evidence

Physical (or Real) Evidence consists of objects that have a firsthand role in the case. The classic example is a murder weapon. From our earlier car crash example, someone might bring in the part that broke, or they could bring in the same model of that part to show what it looked like before it broke. In a case involving a contested will, a copy of the will itself would be a very important exhibit.

Documentary Evidence and Electronic Evidence

Most cases make heavy use of documents and/or electronic records as evidence. Most of our transactions and correspondences are recorded in one or both forms. Contracts, sales records, birth certificates, marriage licenses, company policies, medical patient charts, and patent filings are just a few examples of documents that may be critical in proving one’s arguments in a given case.

These days, an increasing quantity of information exists in electronic form. Companies keep records electronically. E-mails, text messages, videoconferences, and electronic voicemail messages document many of our communications with one another. Information from photographs and videos to contracts and spreadsheets are no longer “printed out”. The evidence of our existence lives on hard drives, servers, and cyber clouds.

When you want to use documents and electronic records, the main trick is to authenticate them. You need to prove that they are original, unadulterated records. How can you ensure this and convince a judge and jury that they are reliable pieces of evidence? Depending on the type of record, there are several different methods of demonstrating their reliability.

First, many government documents are self-authenticating. For example, if you are seeking to have the court admit evidence in the form of a marriage license, property deed, or police report, generally the only thing you need is the document with a seal or signature of the official who prepared it. These documents are presumed to be authentic. If a photocopy is signed or sealed by an appropriate official, it also can be admitted as a certified copy.

Most other documents and electronic records should be authenticated by a witness. This is more expensive and time-consuming, but it is the best way to establish your evidence as reliable for the judge and jury. The attorney can call a witness to the stand, swear her in, introduce her to the court, and begin to lay the groundwork. After establishing she was at the right place and time with her cell phone camera, the attorney could hold up a picture and ask “Is this a copy of the picture you took just after the accident?” With a simple “yes”, the picture has been authenticated. The attorney probably would need to elicit some additional information about the file’s chain of custody since then, but basically the authentication has been accomplished.

“Is this your signature on the contract?” “Is this a copy of the insurance investigation report you prepared?” And to authenticate physical evidence, “Is this the torn piece of clothing you found at the murder scene?” You get the idea here; evidence is more reliable once someone has confirmed it is the real deal.

Electronic files can be stored on a hard drive, server, or somewhere out in the cloud. But how do we know that someone did not open a file containing an important contract, change the word “must” to “must not” and then save the file before closing it again? We know this because all such files are embedded with something called meta information.

This meta data can tell us if a file has been kept in its original form or changed in any way since. Anyone who uses electronic files as evidence must be able to prove they are in their original, intended format. All large companies have policies now for saving electronic information in a form that is verifiable. Again, a witness could be used to explain this to the judge and jury.

Witness Testimony

Another common form of evidence is witness testimony. In order to testify, a witness must be competent and capable of being understood by the jury. There are two kinds of witnesses: lay witnesses and expert witnesses.

A lay witness is someone who has seen, heard, or otherwise perceived something firsthand. And of course, what they perceived and what they are testifying about must be relevant, adding something to the jury’s understanding of the case. A good witness is someone who seems likeable, believable, and honest. Since the witness’ credibility can be attacked, it is important to be sure the person does not have any major weak points that can quickly cast doubt on their veracity, such as poor eyesight, a history of not telling the truth, or persistent alcohol and drug problems.

A lawyer often will use witnesses to authenticate other pieces of evidence. For example, a police officer who examined a crime scene may have found a smoking gun or a shoe and took it into evidence. The police officer would be called to the witness stand to testify that this exhibit was indeed the item that she found at the scene, or that another exhibit indeed appears to be an accurate photo of that location. Or if a contract is in dispute at a trial, someone familiar with that document may be called to testify that yes, that is a copy of the contract in question. Authenticating evidence this way makes it more credible, and more likely to influence a jury.

Expert witnesses did not experience anything firsthand; they are called for their ability to analyze complex subject matter and help the judge and jury make sense of it. An expert can be anyone with above average knowledge of a subject, and that knowledge can be gained through either education or experience. The use of experts is rather controversial, because they are extremely expensive to hire and they tend to agree with whoever is hiring them. When one side hires an expert, the opposing party needs one, too, and a trial can turn into a battle of the experts. If they did not see, hear, or experience something in the case, why are they testifying as witnesses?

It makes sense to call in expert witnesses for cases that involve complex subjects. Perhaps experts are overused, but they are helpful to the judge and jury when the subject matter becomes too specialized. For example, in a medical malpractice case involving some highly specialized form of neurosurgery, is a typical jury really going to understand the arguments and testimony? In a malpractice case, the plaintiff is claiming professional negligence, so ultimately the jury is being asked to determine whether the defendant properly followed the acceptable standard of care in the field. An expert can help explain what kind of procedure and care is typically expected in such a surgery, allowing the jury to decide whether the defendant’s conduct measured up.

Evidence Categorized by Function

Evidence also can be grouped into different categories based on its function. Viewed this way, there is direct evidence, circumstantial evidence, and cumulative/corroborative evidence. In terms of their value, there is no real difference, as courts do not value one kind of evidence over another. Here is a brief rundown of each type.

Direct evidence is proof that forms a firsthand link to the circumstances of the case. An example from criminal law (always the easiest to understand) would be a witness testifying that “I saw the defendant shoot the victim.” If the witness is believable, this is the best information we can get.

Circumstantial evidence is much less direct, yet it brings us half a step closer to fully understanding what happened. “I saw someone who looked just like the defendant leaving the scene of the crime” would be an example. It’s not as good as seeing the crime happen, but it adds a little more to the jury’s knowledge.

There are other forms of evidence that merely add confirmation to evidence that already has been introduced. For example, if Witness A says, “I saw the defendant shoot the victim,” are you inclined to believe her? What if you think she might have a reason to lie? But then the prosecution brings out Witness B who says “I saw the defendant shoot the victim also.” This covers the same ground without adding anything new, but it tends to strengthen the statement that Witness A made. A jury is more likely to believe something is true when they hear it from two or more separate sources.

Limitations on the Use of Evidence

While most evidence can be used in court, the rules prevent certain information from being admitted. All limitations on the use of evidence come from one core policy: courts want the best available evidence. It would take a whole course to explain all the limitations and exceptions on the use of evidence in court. Many lawyers do not understand them all anyway; we have to look them up now and then! Here, we will focus on three common limitations, those affecting the use of hearsay, opinion evidence, and character evidence.

First, let’s understand the basic rules involving hearsay. If you have watched those lawyer shows on TV, then I’m sure you’ve watched a trial scene where an attorney is questioning a witness. Periodically, the other lawyer stands up and yells “Objection! Hearsay!”

Hearsay is secondhand information. In general, secondhand information cannot be used in court, though there are some exceptions that allow it if there is no firsthand information available. To understand how this works, consider this example.

*Ava witnesses a car crash. She tells a police officer that she saw a white SUV crash into a parked car, then drive away from the accident scene at a high rate of speed. After talking to the police officer, Ava calls her friend Selena and tells her the story.

Later, the insurance company that covers the parked car is trying to get paid back for its loss. It has located the white SUV and has sued its owner and insurance carrier. Attempting to establish this link in court, the insurance company (plaintiff) calls Selena to the stand. Selena starts to testify that her friend Ava told her that Ava saw a white SUV hit the parked car and drive off. The opposing lawyer jumps up and screams “ _________! __________!”* (you fill in the blanks).

This is a clear example of hearsay, which should not be admissible in court. Where is Ava, the firsthand witness? Selena did not see, hear, or perceive anything firsthand, but Ava did. Ava, not Selena, can provide the court with the best evidence. While there are exceptions in the law, the general rule is that a court should have the best, most direct evidence possible. Here, that would come from Ava.

There is also a general rule forbidding the use of opinion testimony by lay witnesses. Again, a lay witness is someone who saw, heard, or otherwise perceived something in the case firsthand. While expert witnesses are often asked for their opinions, lay witnesses are not in court to tell us what they think. A lay witness is called into court to tell the jury what he saw, heard, smelled, tasted, or felt. It is the jury’s job, not the witness’ job, to draw conclusions based on this testimony. Here is an example.

Attorney: What color was the vehicle that drove into the parked car?

Witness: White.

Attorney: What type of car did it look like?

Witness: A white SUV. Maybe a jeep.

Attorney: And you saw the white SUV hit the parked car.

Witness: Yes.

Attorney: What did the driver of the SUV do after hitting the parked car?

Witness: Backed up and then drove away really fast.

Attorney: Do you think the driver should have stopped after hitting the other car?

Up jumps the opposing lawyer, who this time screams, “Objection! Calls for Opinion!” And that opposing lawyer is right, because it is the jury’s job (not the witness’) to decide what it means. As with every other general rule, there are exceptions, but it is rare that a lay witness will be able to offer an opinion.

The situation is similar with character evidence, which is not admissible to show that someone acted in conformity with character traits. For example, if George is on trial for stealing money from his employer, the prosecution would not be able to offer evidence that he had two previous arrests for theft. The jury is asked to focus on what happened on the day in question, and whether George violated the law that day.

If the prosecution was allowed to use evidence of George’s past theft arrests, the jury would be much more likely to find him guilty this time. And yet, what George did before is not relevant to whether he did something wrong this time. The only question is whether he violated the law this time.

There is a difficult distinction between character evidence (which is not admissible in court) and habit evidence (which can be admitted). Habit evidence is something more specific, such as that Veronica stops at the corner coffee shop every morning for a cup of coffee. If this evidence is introduced to prove that Veronica probably got the coffee as she normally does, that is acceptable as habit evidence. Usually, character evidence is less specific than habit evidence. However, even lawyers in court may disagree about whether some evidence in a case qualifies as habit or character evidence.

Chapter 9: The Trial

And finally, we come to the heart of the matter. The trial is the definitive moment in litigation, the part you have seen portrayed in so many movies and TV shows. This is the phase where the whole case comes together and is put before the judge and jury for a final resolution.

The drama in a trial is very real. The stakes could not be higher. And while the vast majority of civil cases are settled long before they reach a trial verdict, every single phase of the case is a preparation for this moment. From the filing of the pleadings to the factual investigation and discovery to the frantic pretrial motions and attempts to resolve the case outside of court, it all comes down to these precious few hours in a courtroom.

Courtrooms look pretty much like the ones you see on TV or in legal movies, but there is a lot of variation. Particular states, counties, and court divisions also may appear slightly different. In recent years, most courts have become “smart courtrooms” which include computers, projectors, and the necessary equipment for high tech trial presentations.

The Role of the Judge

The judge is the boss and referee of the courtroom. In a case with a jury, the judge’s role is not to decide the case based on the evidence, but to make rulings of law and ensure that the proper process is followed. The judge must decide questions of law that arise in terms of the admissibility of certain evidence, the application of the law that is used in the case, and matters of procedure such as proper witness questioning, jury selection, and jury instructions. Any one of these decisions can be appealed later on by the losing party.

Under the Seventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, defendants in many federal civil cases have the right to a jury trial (just as criminal defendants do under the Sixth Amendment). This is true in most state courts as well, provided the amount of money involved puts the case in civil court rather than in small claims.

However, a civil defendant in most courts can waive his right to a jury trial, which leaves the judge to decide the case as fact finder. This is known as a bench trial, and it usually progresses more quickly since no jury needs to be selected or instructed. Some defendants choose a bench trial for strategic reasons because they think a jury can get rather emotional in a case and may be swayed by facts or testimony, while a judge should recognize that the law is on their side.

The Jury’s Role and the Civil Standard of Proof

Members of the jury are the fact finders in a case. These members of the public are called in to do their civic duty, which is to hear the evidence and to decide if the plaintiff (or prosecution in a criminal case) has proven his case. Essentially, they are presented with the facts of the case by each party, and then asked to decide whether this measures up to the description of the legal standard that the judge has given them.

While the standard for a criminal conviction is beyond a reasonable doubt (the jury must believe with a very high degree of certainty that the defendant did it), the civil standard of proof is lower. In most civil cases, the plaintiff must prove his case by a preponderance of the evidence, which means something greater than a 50% certainty. No wonder O.J. Simpson was acquitted of murder in criminal court, but then found liable (on the same facts) for wrongful death in civil court.

The jury’s participation begins with the selection of the jurors. If you’ve ever been summoned to jury duty, then you have seen this take place firsthand. The county clerk or official in charge sends out a jury summons to a certain number of local citizens whose names and addresses have been taken from driver license and voter registration records. The court may ask potential jurors to fill out a form with some simple questions that cover age, employment, marital status, and the like. When this pool of potential jurors is brought into the courtroom, one member at a time is randomly selected to be seated in the jury box.

At this point, the judge and attorneys will conduct a process called voir dire, which is where they see and hear from each potential juror. Though this seems to take a long time if you are sitting and waiting in the courtroom, the process moves very quickly for the attorneys. In a typical case, they really just have a couple of minutes to evaluate each juror and decide if he or she can be fair in the case. They ask questions to determine whether potential jurors have any biases that could affect the case.

For example, if the defendant in the case is a car company which allegedly made a defective product, they may ask a potential juror if he has ever been in a car accident, ever been a party in a case, even driven a car made by the defendant company, or ever been injured by a product. If any biases are obvious, then the court will excuse that potential juror for cause, and another potential juror will be seated instead. Each attorney also has a certain number of challenges they can use to excuse jurors for almost any reason (except a discriminatory one). It can be as simple as the attorney not liking the way that potential juror looks at the plaintiff.

Once a full slate of jurors is seated and acceptable to the judge and attorneys, the case can begin. Federal civil cases can have anywhere from 6-12 jurors, while federal criminal cases need 12 jurors and at least one alternate juror. State rules vary, but usually they require a minimum of 5-6 jurors for civil cases. In civil cases, the verdicts do not need to be unanimous, but state law may require that a certain majority of the jurors agree on the verdict.

Opening Statements

Attorneys begin the case by making their opening statements. Normally, the plaintiff in a civil case will lead off. The attorney will introduce himself and his client to the jury, outlining the case he plans to present. The opening statements are engaging, persuasive, and just long enough for jurors to get an introduction to the storyline. If the story gets too long, they will lose interest, but an attorney who is likeable and tells a compelling story can hold them all the way through.

The plaintiff’s attorney will present a short, persuasive summary of the what happened in the case. He will reference any star witnesses or damning evidence that will be presented during the trial. He will explain that the evidence will show his client was injured due to the defendant’s unlawful conduct.

Once he sits down, the defendant’s attorney will introduce himself and his client, countering the plaintiff’s outline of the case with his own version. Usually, this will focus heavily on what the plaintiff cannot prove, and what is missing or lacking as far as the full case. The opening statement is the defendant’s first opportunity to inject some doubt into the minds of the jurors. Ultimately, the attorney will explain, the jurors will conclude by the end of the case that his client cannot be held liable.

The Plaintiff’s Case

After opening statements, the plaintiff will present his case in chief, just like the prosecutor does in a criminal case. The case includes one or more legally recognized claims (also called causes of action), such as negligence, breach of contract, or invasion of privacy. These will be the same claims made in the plaintiff’s complaint, but now the time has come to present the evidence that shows the defendant’s liability under these laws.

The plaintiff’s attorney will make sure to present evidence to establish all elements of the claim. Elements are the essential parts of the law. If, for example, the plaintiff is alleging that the defendant was negligent in failing to inspect the brakes before selling the car, then he must prove the elements of negligence. These vary slightly in different states, but always look quite similar:

1. Duty: The defendant owed a duty of reasonable care to the plaintiff.

2. Breach: The defendant failed to uphold that duty.

3. Causation of Injury: The defendant’s breach of duty was the (actual and foreseeable) cause of the plaintiff’s injury.

4. Damages: As a result of the injury, the plaintiff has suffered damages and demands appropriate compensation.*

Each of these four elements needs to be addressed in the plaintiff’s case. Let’s look at an example of how a plaintiff might prove these elements (possible sources of evidence are in parentheses). This time, the defendant is the car dealership that sold the plaintiff this dangerous car.

1. Duty: A seller of goods warrants that the goods sold are in usable condition (citing laws). In the car selling industry, it is customary to make safety inspections of cars before selling them (testimony from car dealers). Sale of the car by defendant to plaintiff created such a duty (bill of sale, any evidence of transaction).

2. Breach: This seller did not conduct any inspections (testimony of employees, dealer’s business records). The brakes malfunctioned (witness testimony, police report). Forensic analysis of failed brakes concluded that the part had been broken since before the time of the car sale (lab test, expert witness testimony).

3. Causation of Injury: If not for the failed brakes, the accident would not have occurred (police report, expert witness testimony). This accident was foreseeable (expert witness testimony). Plaintiff’s injuries were suffered in this accident (police report, physician’s report, physician’s testimony).

4. Damages: Plaintiff’s injuries are costly (documents and/or testimony: medical bills, lost work time, ongoing treatment for emotional distress, etc).

The plaintiff’s attorney will call witnesses and present evidentiary exhibits to provide proof of each elements. By doing so, he has satisfied his burden of production by presenting a prima facie case for this claim (in our example, negligence). A prima facie case must be good enough that, even if the defendant presented no case, the jury could find the defendant liable for that claim. On the other hand, if the plaintiff has failed to present evidence on one or more elements of the claim, then as a matter of law, the judge would be obligated to step in immediately and enter judgment for the defendant.

During the plaintiff’s case, the defendant’s attorney has only participated in two ways. First, following the plaintiff’s attorney’s direct examination of his own witnesses, the defendant’s attorney has also questioned those witnesses and attempted to knock holes in their stories. This is known as cross-examination. Second, the defendant’s attorney has made any appropriate objections to any evidence or witness questions (“Objection! Hearsay!”) offered by the plaintiff’s attorney. Once the plaintiff’s attorney rests his case, it is the defendant’s turn to take center stage.

Below is a picture of the famous lawyer, Clarence Darrow, presenting a case in about 1911. He is best known for having represented the defendant in the Scopes Monkey Trial.

The Defendant’s Case

The defendant’s attorney also will make use of witness testimony and other evidence to tell the defendant’s side of the story. There are several strategies the defendant can use to make his case. The choice of which one to use largely depends on the case itself, since the facts must support any arguments made in court. Again, as the defendant presents his evidence, the plaintiff’s attorney will raise any necessary objections to direct questions and can cross-examine witnesses as well.

First, the defendant can use the most common approach, which is to knock holes in the plaintiff’s case. If the defendant can disprove (or even introduce enough doubt on) any element of the plaintiff’s case, the jury should decide there is no liability. It is always the plaintiff’s burden to prove liability. So the defendant does not have to prove there is no liability, just that the plaintiff has not proven his claims by a preponderance of the evidence (to a certainty greater than 50%). And he may even introduce evidence that contradicts that which the plaintiff put forth.

For example, using the negligence case again, the defendant’s legal team decides to focus most of its firepower on the “breach” element. The other elements are pretty simple for the plaintiff to prove, but proving the breach depends upon a lab test and an expert opinion, both of which can be attacked. Again, here is a summary of the plaintiff’s case on the breach element.

2. Breach: This seller did not conduct any inspections (testimony of employees, dealer’s business records). The brakes malfunctioned (witness testimony, police report). Forensic analysis of failed brakes concluded that the part had been broken since before the time of the car sale (lab test, expert witness testimony).

Let’s imagine that the lab test revealed some rust on the outside of the broken part. Based on this result, the plaintiff’s expert concluded the part must have broken before the plaintiff had owned the car. Therefore, according to the expert, the part was broken (which a safety inspection would have revealed) at the time of sale. This created the brake malfunction a short time later.

But the defendant can batter the plaintiff’s evidence on this element of the claim. Forget the other elements; if the defendant’s attorney can create enough doubt about the plaintiff’s proof of this single element, then the defendant wins the case. The defendant’s attorney can make the argument that the lab test did not reveal when the break occurred; the plaintiff’s “expert” made this conclusion.

And the expert did not account for the fact that the plaintiff lives and drives in a humid region near the coast, where moist, salty air can corrode things in a hurry. Yes, the brake part was already close to breaking at the time of sale, but if a crack had not appeared yet, then a typical safety inspection would not have revealed it anyway. Quite possibly, the part did not crack until after the sale. The defendant has expert testimony to show this is possible.

Second, a defendant can raise a separate defensive argument that excuses his action. Often, this is known as an affirmative defense. Even if the facts alleged by the plaintiff are basically true, the defendant will explain why he did what he did, and this additional information can provide a reason he should not be liable. A good example of an affirmative defense is the “self defense” argument in response to a charge of murder. “Yes, I killed him, but I was acting in self defense. The guy was about to hack my head off, so I shot him.” If true, that should excuse the defendant’s action in a prosecution for murder, even if every word of the prosecution’s case is true.

In our case of the malfunctioning car, suppose that the defendant’s attorney stands up to present his case and tells the jury, “Everything the plaintiff just told you is correct, but he forgot one thing. The defendant sells used cars, and the plaintiff signed a written purchase agreement to buy the car. That purchase agreement acknowledged that the buyer (plaintiff) was responsible for any inspections and received the car “as is” with no warranties. Not only was there no “breach’ but the defendant did not even owe a “duty” to the plaintiff to inspect the car. The plaintiff voluntarily agreed to assume this risk and we have his signature right here on the contract.” Of course, the defendant’s attorney introduces the contract as evidence and has it authenticated by witness testimony.

A third possibility is to combine these two approaches. The defendant can introduce evidence to raise doubts about certain elements. And if an opportunity exists like the one in the previous example, then a separate defense can be raised as well. Such a defense might apply to only one claim or it may be used on several of them if applicable.

Most civil cases include more than one claim. Instead of just alleging negligence, this plaintiff probably would have included additional claims such as breach of contract, breach of warranty, strict product liability, and fraudulent misrepresentation. Therefore, a separate defense may exist for one or two of those, but the defendant’s attorney would just pound away at the other ones by weakening certain elements. So the mixed approach often works best, but this will depend on the facts.

Closing Arguments

Once the main cases have been presented and each side has rested its arguments, it is time for closing arguments. This phase gives attorneys for each party one final chance to review their cases for the jurors and make their strongest arguments. The judge will hand the case to the jurors soon, so the attorneys will use their closing arguments to recap why the evidence has shown that the defendant should be held liable (from the plaintiff’s perspective) or not liable (from the defendant’s perspective).

Jury Instructions

After closing arguments, the judge will instruct the jury members before sending them to deliberate on the case. The judge’s instructions will clearly explain the jury’s duty and the requirements of the law. While the judge will craft specific jury instructions in every case, usually after taking input from the parties attorneys, each state and court system provides Model Jury Instructions as a place for them to start.

Here is an example of Michigan’s Model Civil Jury Instructions regarding the Burden of Proof in Negligence Cases. Again, these provide the judge with a place to start, but can be customized to fit each actual case. Note that part of these instructions describe comparative fault (assigning a percentage of the liability attributable to the party’s portion of fault), which is the law in some but not all states.

Michigan Model Civil Jury Instructions 16.08

Burden of Proof in Negligence Cases

The plaintiff has the burden of proof on the following propositions:

a. that the defendant was negligent in one or more of the ways claimed by the plaintiff (as stated to you in these instructions)

b. that the plaintiff [was injured / sustained damage]

c. that the negligence of the defendant was a proximate cause of the [injuries / damages] to the plaintiff.

d. Your verdict will be for the plaintiff if you decide that all of these have been proved.

Your verdict will be for the defendant if you decide that any one of these has not been proved.

(The defendant has the burden of proof on [his / her] claim that the plaintiff was negligent in one or more of the ways claimed by the defendant (as stated to you in these instructions), and that such negligence was a proximate cause of the [injuries / damages] to the plaintiff.)