Who decides your diet? [ENG/ITA]

Image CC0 Creative Commons – Source

Everyone reacts to stress differently, but many of the responses manifested concern food in some way. Stress is just one of the examples in which, in response to an emotional condition, one seeks relief in food. Moreover, most of the time it is not just any food, on the contrary there are certain recurrent classes for every mood. Just think of all the times that a depressed person develops a real dependence on sweet foods. All these actions aimed at finding a certain type of food often go unnoticed or are associated with particular antidepressant properties of the food in question, without dwelling too much on the real mechanism that leads to this insatiable research. Leaving aside for a moment what can be the result of a rooted addiction and focusing on what is the behavior of research, we have never wondered what is actually the mechanism that drives us to look for a food rather than another? And if we were not the only ones to decide what to eat? Before finding an answer to these questions it is necessary to thoroughly analyze how our gastrointestinal system is structured.

The advantage of a symbiosis

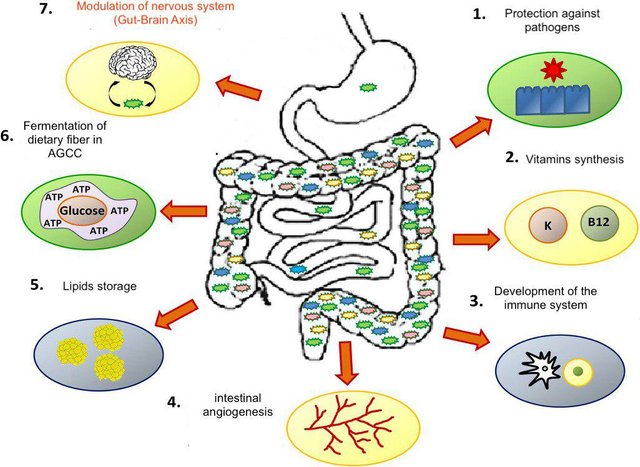

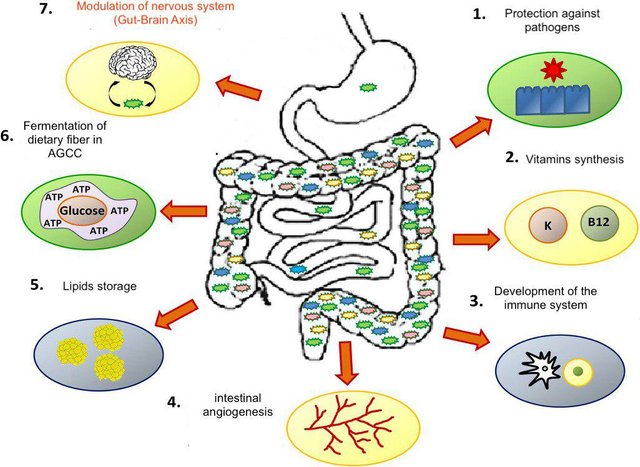

One of the most studied and fascinating forms of symbiosis concerns us very closely, more precisely, in addition to all the microorganisms that we carry with us every day, we are talking about the intestinal microbiota. An intestinal microbiota means a real ecosystem composed of a community of bacterial microorganisms that is found in variable composition in various portions of the intestine. Within the gastrointestinal tract there are kilos of bacteria, a fair mass concentrated in some parts of the body, in equilibrium with the host's immune system and with a remarkable metabolic capacity (ability to code for over 300,000 proteins). The mass is not uniform along the stretch, the bacterial charge is very high in the final portion of the intestine (colon, rectum) and is relatively low in the initial portions of the intestine. In the stomach it tends to be extremely low and is interesting because of the acidic pH are selected some bacterial species that are absent in other places.

Image CC BY-SA 4.0 - Source

To this mass also corresponds a diversity, according to some definitions of the bacterial species, in the intestine can be up to 1000 different bacterial species. Achieving a correct colonization has implications on the development and, above all, on the balanced functioning of the immune response. It has been shown that immune-mediated diseases such as allergies, or inflammatory intestinal forms are linked to an incorrect composition of the microbial community in the early stages of life. For this reason the intestinal microbiota plays a role of fundamental importance from the beginning. Indeed, it has been shown that lines of mouse models, maintained in the same environmental conditions, can develop a normal or overweight phenotype in relation to the microbial community. Furthermore, it was seen that this condition was reversible by means of a transplant of the microbial community. Part of this microbial community is transmitted vertically from the mother to the progeny, which is a condition that at an evolutionary level favors the maintenance of a symbiotic relationship. This is because the fitness of the host is closely related to the fitness of the symbiont, so in a vertical transmission system it suggests the symbiote to operate so that the host can be healthy and able to reproduce bringing benefits to both. However, this symbiosis works because there is a strict balance with the immune system and with the nutrients. Until the last decade, much of the knowledge on intestinal absorption was limited to considering the products of digestion. In fact, it was common to think that the food, after having undergone all the digestive processes, arrived in the intestinal lumen where, thanks to the enterocytes, it passed into the bloodstream. Today it is known that the intestinal microbiota plays an active role in the process of digestion and absorption and in the course of evolution has allowed the conquest of enormous advantages. Just think of the fact that mammals are not able to digest cellulose, but there are animals like ruminants that use particular bacteria, cellulosolytic, that do it for them.

Image CC0 Creative Commons – Source

Symbiosis or battleground?

Considering what has been said so far regarding the symbiotic relationship, it might be interesting to analyze the advantages on both sides. The advantages that an organism obtains in having the symbionts in the gastrointestinal tract are innumerable since, in a certain sense, it represents an extension of the digestive capacity of the organism itself. No mammal is able to digest cellulose, unless there are cellulosolytic symbionts that perform this task in its place. A very studied example is the ruminal environment in which, thanks to the action of bacteria, protozoa and molds, ruminants are able to digest cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, pectic substances, disaccharides and simple sugars. It is therefore evident that these microorganisms provide a ruminant herbivore with the ability to digest substances that otherwise could not be digested. Likewise, the direct advantage of the symbionts is to live in an environment that is continually supplied with substances that are necessary for their survival. In this way it seems that, being able to put the advantage of both sides on a scale, there is a fairly balanced situation. In fact, there are more than 1000 different bacterial species and the microbial and human genes are in a ratio of 100 to 1 in the intestinal microbiome, this leads to the belief that there may be as many common interests as there are divergences with opportunities for mutual benefit and manipulation by the microbiota. According to this vision, man could be the unaware victim of intense competition for nutrients and habitats among the different members of the intestinal microbiota. In fact, it is hypothesized that, on the whole, the genes of the bacteria that make up the microbiota can in some way influence the physiology and behavior of the host organism in order to benefit from it. Making a concrete example, if an amilolitic bacterium had the ability to push the host to prefer foods rich in starch, it would have a big advantage compared to other bacterial species that need other types of nutrients. In this way, highly diversified populations would correspond to greater possibilities of spending energies and resources in competition, vice versa a less diversified population would correspond to species with large population size and greater power to manipulate the host. For this reason, this last condition is hypothesized must be associated with alterations in the behavior of food research (obesity, unhealthy diet ...).

Micro-organisms like skilled puppeteers

In order to exist a competition for a substrate it is necessary to take into account the fact that certain bacteria prefer and have advantages from specific nutrients. In humans, for example, there are bacteria that grow in affinity with carbohydrates such as Akkermansia mucinophila or Prevotella, in Japan even microbes specialized in the digestion of algaehave been isolated from humans as Zobellia galactanivorans. In this way, the nutritive composition of the diet becomes fundamental for microorganisms since, according to this vision, they are highly dependent on it. Usually we are rightly inclined to think that the choice of a food rather than another belongs solely to us. However, there is evidence of a connection between the composition of the intestinal microbiota and the cravings or, in any case, the behavior of the host. On the other hand, there are many cases in which the involvement of a microorganism in the handling of host behavior has been demonstrated. This is the case of butyrate, for example, which, widely produced by the intestinal microbiota, is able to have effects on the central nervous system and on the mood of mice in experimental tests. Another example, of which we have already spoken, concerns the ability of Toxoplasma gondii to manipulate a mouse to such an extent that it urges him to actively search for his executioner's urine. It is evident that, to get to the manipulation of the host, there must be a connection between the intestine and the nervous system that constitutes a direct highway to behavior. A key role could be covered by the vagus nerve. in an experiment conducted by mice fed with Lactobacillus rhaminosus if placed in a full cylinder of water it was seen that, by comparing the control groups with the exposed ones, in the latter a level of cortisol was detected induced by far less stress and, at the same time, an increase in the determination that led them to swim incessantly. This effect disappears when the vagus nerve is severed suggesting an involvement of the latter in the handling of the host.

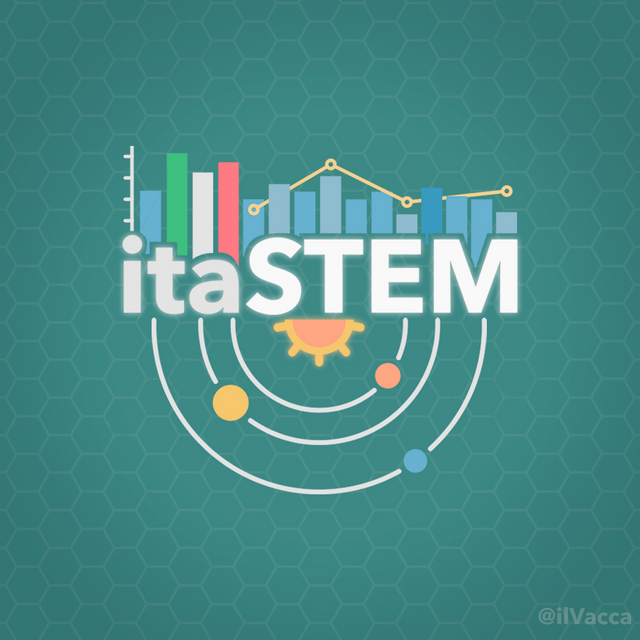

The appearance of the enteric nervous system

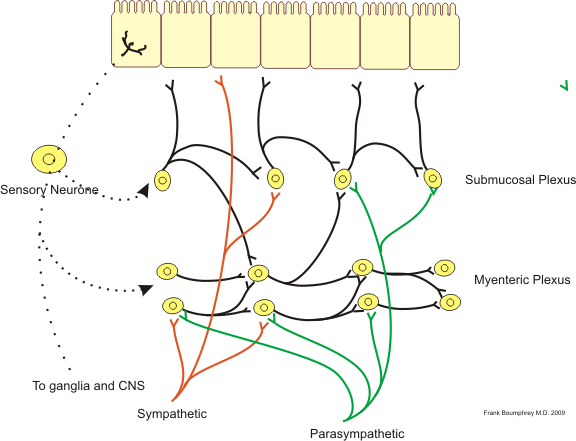

At the level of the intestine we have two layers of muscles, one circular (lumen) and the other longitudinal (external). The function of these two combined layers is peristalsis and to push food towards the colorectal. Peristalsis is an organized contraction that allows the thrust of food through the contraction of the upstream muscle and the simultaneous release of the downstream muscle. As a consequence there is a wave of contraction and dilation near the bolus and, in order to coordinate muscle contraction, the involvement of the nervous system is necessary. Between the two muscular fiber systems there are particular structures called plessi: a myenteric plexus between the longitudinal and the circular layer, and a submucous layer below the circular layer. With in-depth studies in the last decade this system of plexuses has taken the name of "enteric nervous system", in this way it is recognized that both the physiology of the intestinal canal is controlled by a relatively autonomous nervous system, and the fact that the number of neurons in the enteric nervous system is higher than the number of neurons in the spinal cord. The physiology of the digestive system, therefore, can not be separated from the presence of the enteric nervous system. In addition to this, brain neurons are classified into exciters and inhibitors depending on the activity or neurotransmitters. In the intestine are represented all the neurons that we also find in the brain, so complexity of the enteric nervous system is very high and has the very important function of regulating peristalsis. For the same reason that when we are in a condition of nervousness there are problems of digestion, we started to think that the nervous system has a precise effect on the enteric nervous system and it has been shown clearly that neural factors are able to act on the intestine.

Image CC BY-SA 3.0 – Source

In reality there is not a clear trait that goes from the brain to the intestine, but it is noted, for example, that depressed people are more susceptible to infections. Therefore, in recent years, what has been called the cerebro-intestinal axis has been defined from an anatomical point of view. There is evidence of encephalous substances that act through the immune system on intestinal homeostasis and on the functionality of the enteric nervous system. The question that remains is whether, in addition to having a flow of information that goes from the central nervous system to the enteric nervous system, there is one in the opposite direction. For example, some bacteria produce substances such as tryptophan, which are naturally precursors for the metabolism of serotonin which is a neurotransmitter. It is thought that the production of these metabolites by the bacteria has an action on the enteric nervous system being close to this, as well as with the immune system. In some ways this type of signal changes the behavior of organisms that harbor a bacterial flora. In the evolutionary perspective of a bacterium that produces a large amount of tryptophan, which in turn acts on the enteric nervous system and regulates peristalsis, it induces behavioral changes in the search for food that, if they are successful for this bacterium, are selected.

Some possible ways of manipulation

Being a relatively new field, there are countless researches in progress to determine all the possible mechanisms with which the microbiota could determine a modification of the alimentary behavior. There are three examples that make the idea of what has been said so far and can help to understand the extent of this mechanism. The first is the case of the inconsolable crying of infantile colic. Recent studies have correlated this behavior with variations of the intestinal microbiota including a greater concentration of protobacteria at the expense of bacteroidetes, and a consequent reduction of intestinal diversity. The moment a child cries attracts the attention of parents and, in most cases, pushes the latter to feed it. At the same time, colic can lead to an increase in the release of resources from the intestine and therefore greater access by micro-organisms to nutrients. All of this involves, in some way, the perception of pain. The production of virulence toxins is often triggered by a low concentration of nutrients. In these conditions the guests determine damage to the intestinal epithelium by increasing the possibility of manipulating the host's behavior through pain signaling. Another example is the possibility of modulating the expression of the receptors of the host. It has been shown that oral administration of Lactobacillus acidophilus as a probiotic to mice and rats increases the intestinal expression of the cannabinoid and opioid receptors, resulting in similar effects in cultures of human epithelial cells. Although research is limited to epithelial cell cultures, this also suggests that the microbiota could influence food preferences by altering the expression of certain receptors. Finally, another hypothesis is that microorganisms can influence guests through hormones. Most of the serotonin and more than 50% of dopamine have an intestinal source, because intestinal microorganisms such as Escherichia coli or Staphylococcus aureus have the ability to produce many hormone-like neurochemicals that in mammals are involved in behavior and mood. In addition to this, a number of pathogenic and commensal bacteria are able to produce peptides very similar to hormones that, in mammals, regulate hunger and satiety. At the same time, humans and other mammals produce antibodies directed against these microbial peptides, however, these antibodies also act against the hormones of the mammals themselves. This autoimmune response implies the possibility of microorganisms to have control through two mechanisms, one direct and one indirect. They can directly produce peptide mimics of the hormones that regulate satiety, or indirectly can stimulate the production of autoantibodies that interfere with the regulation of appetite. This last aspect supports the hypothesis that the conflict between microbiota and host can have a certain influence on the regulation of alimentary behavior.

A small zoom on some forms of autism

Mutations in the nervous system that did not select for the enteric nervous system or the brain were observed in some forms of autism with genetic manifestation, for this reason very strong associations between behavioral alterations and alterations of the intestinal tract were observed. These changes include abdominal discomfort, changes in intestinal habits and swelling. In addition to the genetic forms, the late-onset forms (onset over 18 months) are also in the viewfinder in which organisms such as Desulfovibrio spp. And various clostridia are involved. Initially it was thought that, in some cases, the responsibility was borne by Clostridium spp since some forms of autism are detected following prolonged use and abuse of antibiotics. Some of these antibiotics cause the onset of this bacterium that is known to have postnatal influence on brain development and function. However, with modern knowledge it has been possible to verify that, in reality, the range of microorganisms involved is much wider. By intestinal biopsy on subjects with late-onset autism spectrum disorders, it was possible to detect a decrease in Bifidobacterium spp. And Akkermansia muciniphila and many other changes compared to control subjects. The highlighted microbial profile is associated with a decrease in the ileal transcripts involved in the coding of disaccharidase and hexose transporters which leads to a malabsorption of carbohydrates. The fact that a voluminous portion of carbohydrates is not absorbed determines the presence of a substrate that can be used by microorganisms which, potentially, can cause various forms of intestinal dysbiosis. This condition could be involved in the increasingly frequent link between behavioral disorders of the autistic spectrum and intestinal disorders. It is equally possible that microorganisms play a role in the manifestation of autism spectrum alterations by intervening directly on the development of the fetal brain. However, at the moment there seem to be no correlation between the maternal profile and the forms of autism or different behavioral alterations in the offspring and it is a field still in the process of exploration because of the infinite forms that arise for such complicated and still not fully understood diseases.

Conclusions

The fact that there can be such a control has significant implications on the conception of many metabolic disorders such as obesity, or behaviors that lead to preferring different foods. In fact, all this opens the door to a field that has not yet been studied, which identifies the microbiota transplant as a possible cure for certain food pathologies. In a sense it is as if food preferences could be contagious and, since a relative's food preferences could influence the whole family's diet, any type of intestinal microorganism adapted to that diet would tend to thrive in other members of the family. In this way, members of the same family would find themselves having a much more similar fecal and oral microbiota than an external member. A good correlation could directly concern food preferences and the reason why we find ourselves having to deal with cravings. It has always been thought that the cravings come from a lack of nutrients, but these also affect periods of abundance and often the nutrients that are sought are not those that could fully fill the shortage. At the extreme there are even people who practice geophagy or coprophage for which, beyond a psychological component, has been proven a lack of correlation with a scarcity of nutrients, this implies that there must necessarily be another reason that can explain these behaviors and could concern this area. Ultimately, many studies on the effects of intestinal microbes on health and behavior still have many questions to answer. However, the genetic conflict between microbiota and host opens up a path that widens existing points of view and could give a different version to mechanisms involved in obesity and diseases related to the gastrointestinal system.

Chi decide la tua dieta?

Image CC0 Creative Commons – Source

Ognuno reagisce allo stress in modo diverso, ma tante delle risposte manifestate riguardano in qualche modo il cibo. Lo stress è solo uno degli esempi nei quali, in risposta a una condizione emotiva, si cerca sollievo nel cibo. Per di più, la maggior parte delle volte non si tratta di un alimento qualunque, al contrario ci sono determinate classi ricorrenti per ogni stato d’animo. Basti pensare a tutte le volte che una persona depressa sviluppa una vera e propria dipendenza nei confronti di alimenti dolci. Tutte queste azioni volte alla ricerca di un determinato tipo di cibo passano spesso inosservate o vengono associate a particolari proprietà antidepressive del cibo in questione, senza soffermarsi troppo sul reale meccanismo che porta a questa insaziabile ricerca. Tralasciando per un attimo ciò che può essere frutto di una dipendenza radicata e concentrandoci su quello che è il comportamento di ricerca, ci siamo mai domandati quale sia effettivamente il meccanismo che ci spinge a cercare un cibo piuttosto che un altro? E se non fossimo solo noi a decidere cosa mangiare? Prima di trovare una risposta a queste domande occorre analizzare a fondo come sia strutturato il nostro sistema gastroenterico.

Il vantaggio di una simbiosi

Una delle forme di simbiosi più studiata e affascinante ci riguarda molto da vicino, più precisamente, oltre a tutti i microrganismi che portiamo con noi ogni giorno, stiamo parlando del microbiota intestinale. Per microbiota intestinale si intende un vero e proprio ecosistema composto da una comunità di microrganismi batterici che si trova in composizione variabile in vari tratti dell’intestino. All’interno del tratto gastroenterico sono presenti chili di batteri, una discreta massa concentrata in alcune parti del corpo, in equilibrio con il sistema immunitario dell’ospite e con una capacità metabolica notevole (capacità di codificare per oltre 300.000 proteine). La massa non è uniforme lungo il tratto, la carica batterica è molto alta nella porzione finale dell’intestino (colon, retto) ed è relativamente bassa nelle porzioni iniziali dell’intestino. Nello stomaco tende ad essere estremamente bassa ed è interessante perché proprio per il pH acido vengono selezionate delle specie batteriche che sono assenti in altri posti.

Image CC BY-SA 4.0 - Source

A questa massa corrisponde anche una diversità, secondo alcune definizioni della specie batterica possono essere presenti nell’intestino anche 1000 diverse specie batteriche. Il raggiungimento di una corretta colonizzazione ha implicazioni sullo sviluppo e, soprattutto, sul bilanciato funzionamento della risposta immunitaria. È ormai dimostrato che patologie a base immunomediata come allergie, o forme infiammatorie intestinali siano legate e una non corretta composizione della comunità microbica nelle prime fasi di vita. Per questo motivo il microbiota intestinale riveste un ruolo di fondamentale importanza fin dall’inizio. Addirittura, è stato dimostrato che linee di modelli murini, mantenuti nelle stesse condizioni ambientali, possono sviluppare un fenotipo normopeso o sovrappeso in relazione alla comunità microbica. Inoltre, è stato visto come questa condizione fosse reversibile per mezzo di un trapianto della comunità microbica. Parte di questa comunità microbica viene trasmessa verticalmente dalla madre alla progenie, il che è una condizione che a livello evolutivo favorisce il mantenimento di un rapporto simbiotico. Questo perché la fitness dell’ospite è strettamente correlata alla fitness del simbionte, quindi in un sistema a trasmissione verticale suggerisce al simbionte di operare affinché l’ospite possa essere in salute e in grado di riprodursi portando vantaggi a entrambi. Tuttavia, questa simbiosi funziona perché c’è un rigoroso equilibrio con il sistema immunitario e con le sostanze nutrienti. Fino al decennio scorso, gran parte della conoscenza sull’assorbimento intestinale si limitava a considerare i prodotti della digestione. Infatti, era comune pensare che il cibo, dopo aver subito tutti i processi digestivi, arrivasse nel lume intestinale dove, grazie agli enterociti, passasse nel circolo sanguigno. Oggi si sa che il microbiota intestinale ha un ruolo attivo nel processo di digestione e assorbimento e nel corso dell’evoluzione ha permesso la conquista di enormi vantaggi. Basti pensare al fatto che i mammiferi non sono in grado di digerire la cellulosa, ma ci sono animali come i ruminanti che si avvalgono di particolari batteri, cellulosolitici, che lo fanno al posto loro.

Image CC0 Creative Commons – Source

Simbiosi o terreno di battaglia?

Considerando quanto detto finora riguardo al rapporto simbiotico, potrebbe essere interessante analizzare i vantaggi da entrambe le parti. I vantaggi che trae un organismo nell’avere dei simbionti nel tratto gastrointestinale sono innumerevoli poiché, in un certo senso, rappresenta un’estensione delle capacità digestive dell’organismo stesso. Nessun mammifero è in grado di digerire la cellulosa, a meno che non presenti dei simbionti cellulosolitici che svolgono questo compito al posto suo. Un esempio molto studiato è l’ambiente ruminale nel quale, grazie all’azione di batteri, protozoi e muffe, i ruminanti sono in grado di digerire cellulosa, emicellulosa, amido, sostanze pectiche, disaccaridi e zuccheri semplici. È quindi evidente che questi microrganismi forniscono a un erbivoro ruminante la capacità di digerire sostanze che, altrimenti, non potrebbero essere digerite. Allo stesso modo il vantaggio diretto dei simbionti è quello di vivere in un ambiente continuamente rifornito di sostanze che sono necessarie alla loro sopravvivenza. In questo modo sembra che, potendo mettere su una bilancia il vantaggio di entrambe le parti, ci sia una situazione abbastanza equilibrata. In realtà, ci sono più di 1000 specie batteriche diverse e i geni microbici e quelli umani si trovano in un rapporto di 100 a 1 nel microbioma intestinale, questo porta a pensare che ci possano essere tanti interessi comuni quante divergenze con opportunità di mutuo vantaggio e manipolazione da parte del microbiota. Secondo questa visione l’uomo potrebbe essere la vittima inconsapevole di un’intensa competizione per sostanze nutritive e habitat tra i diversi membri del microbiota intestinale. Si ipotizza infatti che, nel complesso, i geni dei batteri che compongono il microbiota possano in qualche modo influenzare la fisiologia e il comportamento dell’organismo ospite in modo da trarne un beneficio. Facendo un esempio concreto, se un batterio amilolitico avesse la possibilità di spingere l’ospite a preferire cibi ricchi di amido, avrebbe un grosso vantaggio rispetto ad altre specie batteriche che necessitano di altre tipologie di nutrienti. In questo modo, popolazioni altamente diversificate corrisponderebbero a maggiori possibilità di spendere energie e risorse in competizione, viceversa una popolazione meno diversificata corrisponderebbe a specie con ampie dimensioni di popolazione e maggiore potere per manipolare l’ospite. Per questo motivo, quest’ultima condizione si ipotizza debba essere associata ad alterazioni nel comportamento di ricerca alimentare (obesità, alimentazione malsana…).

Microrganismi come abili burattinai

Affinchè ci possa essere una competizione per un substrato è necessario prendere in considerazione il fatto che, effettivamente, determinati batteri preferiscano e abbiano dei vantaggi da nutrienti specifici. Nell’uomo, per esempio, ci sono dei batteri che crescono in affinità con i carboidrati come Akkermansia mucinophila o Prevotella, in Giappone addirittura sono stati isolati dall’uomo dei microbi specializzati nella digestione delle alghe come Zobellia galactanivorans. In questo modo, la composizione nutritiva della dieta diventa fondamentale per i microrganismi dal momento che, secondo questa visione, ne sono altamente dipendenti. Di solito siamo giustamente portati a pensare che la scelta di un alimento piuttosto che un altro spetti unicamente a noi. Tuttavia, ci sono evidenze di una connessione tra la composizione del microbiota intestinale e le voglie o, comunque, il comportamento dell’ospite. D’altra parte, ci sono molti casi in cui è stato dimostrato il coinvolgimento di un microrganismo nella manipolazione del comportamento dell’ospite. È il caso del butirrato, per esempio, il quale, ampiamente prodotto dal microbiota intestinale, è in grado di avere effetti sul sistema nervoso centrale e sull’umore di topi in prove sperimentali. Un altro esempio, del quale abbiamo già parlato, riguarda la capacità di Toxoplasma gondii nel manipolare un topo a tal punto da spingerlo a cercare attivamente l’urina del proprio carnefice. È evidente che, per arrivare alla manipolazione dell’ospite, debba esserci un collegamento tra l’intestino e il sistema nervoso che costituisca un’autostrada diretta verso il comportamento. Un ruolo fondamentale potrebbe essere ricoperto dal nervo vago. In un esperimento condotto per mezzo di topi nutriti con Lactobacillus rhaminosus se posti in un cilindro pieno d’acqua si è visto che, mettendo a confronto i gruppi di controllo con gli esposti, nei secondi si rilevava un livello di cortisolo indotto da stress di gran lunga minore e, allo stesso tempo, un aumento nella determinazione che li spingeva a nuotare incessantemente. Questo effetto scompare quando viene reciso il nervo vago suggerendo un coinvolgimento di quest’ultimo nella manipolazione dell’ospite.

La comparsa del sistema nervoso enterico

A livello dell’intestino abbiamo due strati di muscoli, uno circolare (lume) e l’altro longitudinale (esterno). La funzione di questi due strati combinati è la peristalsi e lo spingere il cibo verso il colon-retto. La peristalsi è una contrazione organizzata che consente la spinta del cibo tramite la contrazione del muscolo a monte e il simultaneo rilascio di quello a valle. Di conseguenza c’è un’onda di contrazione e dilatazione in prossimità del bolo e, per coordinare la contrazione muscolare, è necessario il coinvolgimento del sistema nervoso. Tra i due sistemi di fibre muscolari sono presenti delle strutture particolari chiamati plessi: un plesso mienterico tra lo strato longitudinale e quello circolare, e un plesso sottomucoso al di sotto dello strato circolare. Con studi approfonditi nell’ultimo decennio questo sistema di plessi ha preso il nome di “sistema nervoso enterico”, in questo modo si riconosce sia che la fisiologia del canale intestinale venga controllato da un sistema nervoso relativamente autonomo, sia il fatto che il numero di neuroni del sistema nervoso enterico sia più alto del numero di neuroni nel midollo spinale. La fisiologia del sistema digerente, quindi, non può prescindere dalla presenza del sistema nervoso enterico. Oltre a questo i neuroni del cervello vengono classificati in eccitatori ed inibitori a seconda dell’attività o dei neurotrasmettitori. Nell’intestino sono rappresentati tutti i neuroni che troviamo anche nel cervello, quindi complessità del sistema nervoso enterico è molto elevata e ha la funzione importantissima di regolare la peristalsi. Per lo stesso motivo per cui quando ci si trova in una condizione di nervosismo si riscontrano problemi di digestione, si è iniziato a pensare che il sistema nervoso abbia un effetto preciso sul sistema nervoso enterico e si è dimostrato in maniera chiara che dei fattori neurali siano in grado di agire sull’intestino.

Image CC BY-SA 3.0 – Source

In realtà non c’è un tratto chiaro che dal cervello vada all’intestino, ma si nota, per esempio, che le persone depresse sono più suscettibili alle infezioni. Negli ultimi anni, quindi, è stato definito dal punto di vista anatomico quello che viene chiamato l’asse cerebro-intestinale. Ci sono evidenze di sostanze prodotte a livello encefalico che agiscono poi attraverso il sistema immunitario sull’omeostasi intestinale e sulla funzionalità del sistema nervoso enterico. La domanda che resta è se, oltre che avere un flusso di informazioni che va dal sistema nervoso centrale al sistema nervoso enterico, ce ne sia uno nella direzione opposta. Per esempio, alcuni batteri producono sostanze come il triptofano, che sono naturalmente dei precursori per il metabolismo della serotonina che è un neurotrasmettitore. Si pensa che la produzione di questi metaboliti da parte dei batteri abbia un’azione sul sistema nervoso enterico trovandosi in prossimità di questo, così come con il sistema immunitario. In qualche modo questo tipo di segnali va a modificare il comportamento degli organismi che ospitano una flora batterica. Nell’ottica evolutiva di un batterio che produce una grande quantità di triptofano, che agisce a sua volta sul sistema nervoso enterico e regola la peristalsi, induce dei cambiamenti comportamentali di ricerca del cibo che, se hanno successo per questo batterio, vengono selezionati.

Alcune possibili vie di manipolazione

Essendo un campo relativamente nuovo, sono innumerevoli le ricerche in corso per determinare tutti i possibili meccanismi con cui il microbiota potrebbe determinare una modificazione del comportamento alimentare. Ci sono tre esempi che rendono particolarmente l’idea di quanto detto finora e possono aiutare a comprendere l’entità di questo meccanismo. Il primo è il caso del pianto inconsolabile della colica infantile. Recenti studi hanno correlato questo comportamento con delle variazioni del microbiota intestinale tra cui una maggiore concentrazione di Protobacteria a scapito di Bacteroidetes, e una conseguente riduzione della diversità intestinale. Nel momento in cui un bambino piange attira l’attenzione dei genitori e, nella maggior parte dei casi, spinge questi ultimi ad alimentarlo. Parallelamente, la colica può determinare un aumento nel rilascio di risorse dall’intestino quindi un maggiore accesso da parte dei microrganismi ai nutrienti. Tutto questo coinvolge, in qualche modo, la percezione del dolore. La produzione di tossine di virulenza è spesso innescata da una bassa concentrazione di nutrienti. In queste condizioni i commensali determinano un danno all’epitelio intestinale aumentando la possibilità di manipolare il comportamento dell’ospite attraverso la segnalazione del dolore. Un altro esempio è la possibilità di modulare l’espressione dei recettori dell’ospite. È stato dimostrato come la somministrazione orale di Lactobacillus acidophilus come probiotico a topi e ratti aumenti l’espressione intestinale dei recettori dei cannabinoidi e oppioidi, determinando effetti simili in colture di cellule epiteliali umane. Sebbene le ricerche siano limitate a colture di cellule epiteliali, questo suggerisce ugualmente che il microbiota potrebbe influenzare le preferenze alimentari alterando l’espressione di determinati recettori. Infine, un’altra ipotesi è che i microrganismi possano influenzare gli ospiti attraverso gli ormoni. La maggior parte della serotonina e oltre il 50% della dopamina hanno fonte intestinale, questo perché i microrganismi intestinali come Escherichia coli o Staphylococcus aureus hanno la capacità di produrre molti neurochimici analoghi agli ormoni che, nei mammiferi, sono coinvolti nel comportamento e nell’umore. Oltre a questo, un certo numero di batteri patogeni e commensali sono in grado di produrre peptidi molto simili a ormoni che, nei mammiferi, regolano la fame e la sazietà. Allo stesso tempo, umani e altri mammiferi producono anticorpi diretti contro questi peptidi microbici, tuttavia, questi anticorpi agiscono anche contro gli ormoni dei mammiferi stessi. Questa risposta autoimmune implica la possibilità da parte dei microrganismi di avere un controllo attraverso due meccanismi, uno diretto e uno indiretto. Direttamente possono produrre dei mimici peptidici degli ormoni che regolano la sazietà, o indirettamente possono stimolare la produzione di autoanticorpi che interferiscono con la regolazione dell’appetito. Quest’ultimo aspetto supporta l’ipotesi che il conflitto tra microbiota e ospite possa avere una certa influenza sulla regolazione del comportamento alimentare.

Un piccolo zoom su alcune forme di autismo

In alcune forme di autismo a manifestazione genetica sono state osservate delle mutazioni a carico del sistema nervoso che non selezionavano per il sistema nervoso enterico o per il cervello, per questo motivo si osservavano delle associazioni molto forti tra alterazioni comportamentali e alterazioni del tratto intestinale. Queste alterazioni includono disturbi addominali, alterazioni delle abitudini intestinali e gonfiore. Oltre alle forme genetiche, si trovano nel mirino anche le forme a insorgenza tardiva (insorgenza in età superiore ai 18 mesi) nelle quali sarebbero coinvolti organismi come Desulfovibrio spp. e diversi clostridi. Inizialmente si pensava che, in alcuni casi, la responsabilità fosse a carico di Clostridium spp dal momento che alcune forme di autismo si rilevano a seguito di un uso prolungato e abuso di antibiotici. Alcuni di questi antibiotici provocano l’insorgenza di questo batterio che è noto avere influenza postnatale sullo sviluppo e funzione cerebrale. Tuttavia, con le conoscenze moderne è stato possibile verificare che, in realtà, la gamma di microrganismi coinvolti è molto più ampia. Tramite biopsia intestinale su soggetti che presentavano disordini dello spettro autistico a insorgenza tardiva, è stato possibile rilevare una diminuzione di Bifidobacterium spp. e Akkermansia muciniphila e molte altre alterazioni rispetto ai soggetti di controllo. Il profilo microbico evidenziato viene associato a una diminuzione delle trascrizioni ileali coinvolte nella codifica di disaccaridasi e trasportatori esosi il che determina un malassorbimento dei carboidrati. Il fatto che una voluminosa porzione di carboidrati non venga assorbita determina la presenza di un substrato utilizzabile per i microrganismi che, potenzialmente, può determinare varie forme di disbiosi intestinale. Questa condizione potrebbe essere coinvolta nel collegamento sempre più frequente tra disturbi comportamentali dello spettro autistico e disturbi intestinali. E’ altrettanto possibile che i microrganismi abbiano un ruolo nella manifestazione di alterazioni dello spettro autistico intervenendo direttamente sullo sviluppo del cervello fetale. Tuttavia, al momento sembrano non esserci correlazioni tra il profilo materno e le forme di autismo o diverse alterazioni comportamentali nella prole ed è un campo ancora in via di esplorazione per via, anche, delle infinite forme che si presentano per delle malattie così complicate e non ancora del tutto comprese.

Conclusioni

Il fatto che ci possa essere un controllo di questo tipo ha delle implicazioni non indifferenti sulla concezione di molti disturbi metabolici come l’obesità, o su comportamenti che portano a preferire cibi diversi. Tutto questo, infatti, apre le porte a un campo ancora poco studiato che identifica come possibile cura di determinate patologie alimentari il trapianto di microbiota. In un certo senso è come se le preferenze alimentari potessero essere contagiose e, dal momento che le preferenze alimentari di un parente potrebbero influenzare l’alimentazione dell’intera famiglia, qualsiasi tipo di microrganismo intestinale adattato a quella dieta tenderebbe a prosperare negli altri membri della famiglia. In questo modo membri della stessa famiglia si ritroverebbero ad avere un microbiota fecale e orale molto più simile rispetto a un membro esterno. Una buona correlazione potrebbe riguardare direttamente le preferenze alimentari e il motivo per cui ci si ritrova a dover fare i conti con le voglie. Si è sempre pensato che le voglie derivino da una carenza di nutrienti, ma queste colpiscono anche in periodi di abbondanza e spesso i nutrienti che si ricercano non sono quelli che potrebbero colmare a pieno la carenza. All’estremo ci sono addirittura persone che praticano geofagia o coprofagia per le quali, al di là di una componente psicologica, è stata provata una mancata correlazione con una scarsità di nutrienti, questo implica che debba necessariamente esserci un altro motivo che possa spiegare questi comportamenti e potrebbe riguardare questo ambito. In definitiva, molti studi sugli effetti dei microbi intestinali sulla salute e sul comportamento hanno ancora molte domande a cui rispondere. Tuttavia, il conflitto genetico tra microbiota e ospite apre una strada che amplia gli attuali punti di vista e che potrebbe dare una versione differente a meccanismi coinvolti nell’obesità e in malattie correlate al sistema gastrointestinale.

Immagine CC0 Creative Commons, si ringrazia @mrazura per il logo ITASTEM.

CLICK HERE AND VOTE FOR DAVINCI.WITNESS

References

- Joe Alcock, Carlo C. Maley, and C. Athena Aktipis (2014). Is eating behavior manipulated by the gastrointestinal microbiota? Evolutionary pressures and potential mechanisms.

https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201400071 - Benjamin Pluvinage, Julie M. Grondin et al. (2018). Molecular basis of an agarose metabolic pathway acquired by a human intestinal symbiont.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03366-x - Weerth C, Fuentes S, Puylaert P, de Vos WM (2013). Intestinal microbiota of infants with colic: development and specific signatures.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1449 - Rousseaux C, Thuru X, Gelot A, Barnich N, et al. (2007). Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1521

- Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, et al. (2014). Gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ.

https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2014-1108) - Song SJ, Lauber C, Costello EK, Lozupone CA, et al. (2013). Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.00458) - Stephen M. Collins, Michael Surette and Premysl Bercik (2012). The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2876 - Williams, B. L., Hornig, M., Parekh, T. & Lipkin, W. I. (2011). Application of novel PCR‐based methods for detection, quantitation, and phylogenetic characterization of Sutterella species in intestinal biopsy samples from children with autism and gastrointestinal disturbances.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1128%2FmBio.00261-11 - Finegold, S. M., Downes, J. & Summanen, P. H. Anaerobe (2012). Microbiology of regressive autism.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.018

Logo creato da @ilvacca

Talk about the placement of gut microbiome, I guess, lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) can pose some problems to the newly born baby since the bacteria which form the bulk of the gut microbiota were originated from the mother's vaginal canal. LSCS bypass this so it is important for us to pay attention to what they (people who born through LSCS) eat early on, am I right?

Yes, you are right. Nevertheless there are many other ways through which children can "educate" their own immune system and develop an adequate bacterial community: breast milk, contact with family members, playing outside... It is important that these stimuli do not lack completely...

This post has been voted on by the steemstem curation team and voting trail.

There is more to SteemSTEM than just writing posts, check here for some more tips on being a community member. You can also join our discord here to get to know the rest of the community!

Hi @spaghettiscience!

Your post was upvoted by utopian.io in cooperation with steemstem - supporting knowledge, innovation and technological advancement on the Steem Blockchain.

Contribute to Open Source with utopian.io

Learn how to contribute on our website and join the new open source economy.

Want to chat? Join the Utopian Community on Discord https://discord.gg/h52nFrV