History of Hunger in Bengal-India

Recognizing and assessing past fatal mistakes has always been a complex and painful process for individuals as well as for the state and humanity as a whole. At the same time, the need to return to grim memories of the past is not only necessary and not so much to uphold justice and seek the guilty, to prevent the repetition of a horrific historical tragedy in the future. One of the most bleak pages of recent historical history is the mass starvation that struck Bengal, the province of British India, in the period 1942-1944.

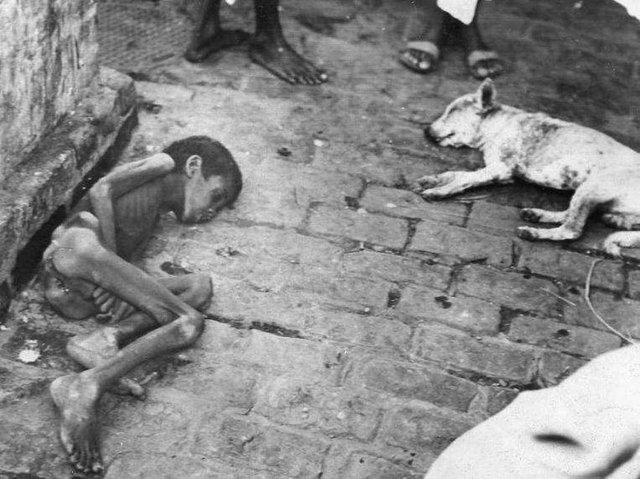

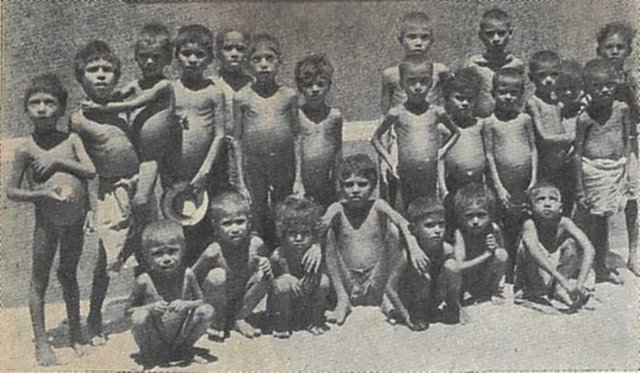

While the main cause of humanitarian disaster is the impact of the Second World War, a number of prerequisites for the emergence of food shortages have developed much earlier. The economy of Bengal province during that period was largely an agrarian orientation. The main agricultural crops, as well as the basic food products of this region, are rice. About 88% of the provinces available for provincial cultivation are involved in rice, providing up to one-third of India's total production. The extensive and less thoughtful nature of management leads to reduced land, decreased quality of seeds, and consequently reduced production efficiency. Negatively affects rice production and natural reclamation disruption in railway construction, causing draining of some areas and extreme swelling of the other. At the same time, the population growth rate in the province is significant. Under such conditions, no less than half of the rural poor live in starvation even before the famine that occurs before the famine. Many farmers were destroyed, and, unable to pay agricultural loans, lost land and equipment for rich landowners.

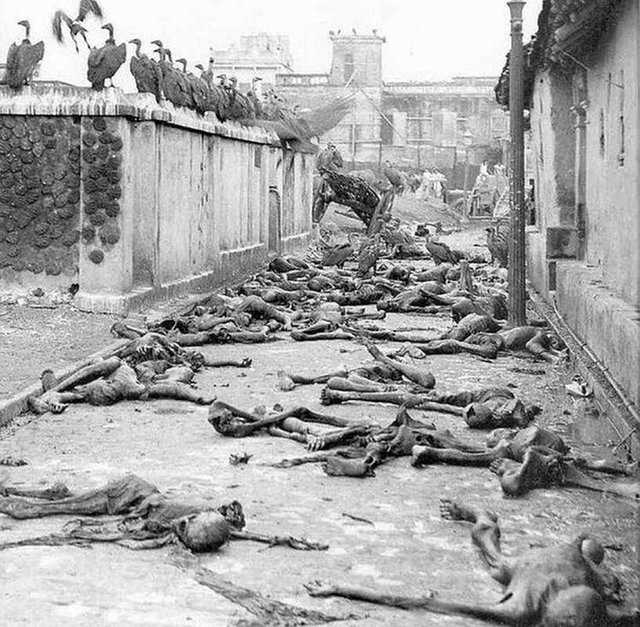

By unexpected coincidence, 1942 proved very bad for Bengal. At the same time, because of the need for war, rice exports from provinces to the United Kingdom and other parts of India are on the rise. The main priority for Churchill's military offices is the provision of food and clothing for strategically important industrial areas in the country, maintaining the viability of the military industry, including through increased exports from agricultural areas. In addition, with the Japanese invasion of Burma in December 1941 embarked on a massive Indian ethnic flight from the region. Refugees flooded Bengal, increasing demand for important products and carrying infectious diseases: malaria, cholera, smallpox. Extremely aggravated by the situation and the powerful cyclone in 1942, destroying over 5,000 square kilometers of beach,

Increased demand for rice has increased prices, intensifying speculation on the black market. Attempts by the British government to influence the situation by limiting the maximum allowable price only leads to seller compliance against stocks and an increase in illicit trade. The request of Indian Foreign Minister Leopold Emery and Vice King Archibald Weiwel to stop the export of food from Bengal was rejected by the military cabinet.

The fall of Rangoon and Burma's capture by Japan makes it impossible to export rice from this country. Afraid of the possibility of expansion from east to Bengal, the British government decided to deprive the enemy's access to the region's main vehicle - rowboats and sailboats. All small boats with a capacity of more than 10 people should be seized or destroyed. But in impassable conditions, especially in the rainy season, only movement through many rivers makes it possible to transport food, seeds and farm equipment. Also in a number of coastal areas, such as Bakarganzh, Midnapor, Khulna, "surplus" rice was forcibly seized to prevent the possibility of their capture by the enemy. Difficulties of transport communication with other provinces,

But not just the lack of food suffered by Bengal. Most of the production of fabric, leather, wool, silk is purchased for military purposes, and at a very low price and on credit. At the same time, Indian banks were given permission to "asset" debt for goods sent to the UK to print large sums of paper money, leading to hyperinflation and a spiral of new price increases.

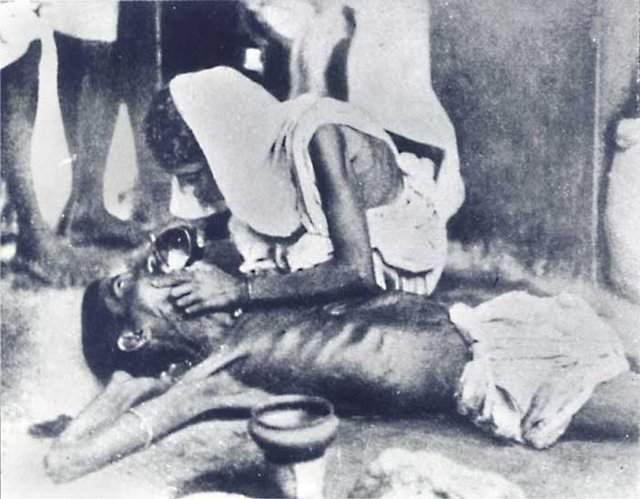

The peak of deaths from Bengal famine occurred in November 1943, in December, most deaths began to occur because the disease spread among the weak: most of all malaria, to lower levels of cholera and smallpox.

Inadequate small and insufficient assistance for government organizations can not significantly affect the situation. One and a half million people are starving in Bengal following a special state commission investigation, but according to the majority of researchers' estimates, this figure is conditional and lacking. But even the most careful and limited judgment can not conceal a surprising scale of tragedy, which mankind can not forget after decades.