Chapter Three: The Investors, or who doesn't need protection.

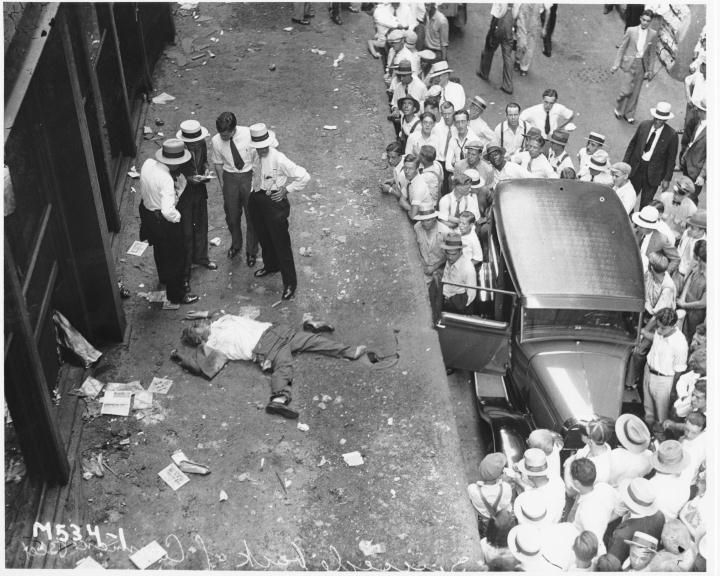

The general rule of securities law is that they were set up to protect the individual investor who has very little money to save, and that the loss of his savings will cause him to jump off a building. We saw that, back in the 1920s.

The fact of the matter is, that while investor protection laws established a presumption that well informed investors need no protection, they lost as much as the individual investors over the years. In this chapter we'll first discuss who are the different investor groups according to the Securities Act, and then we'll see if they are still relevant in this category. I believe that after presenting a few cases, the differentiation the law presents will seem as archaic and misunderstood, and I'll offer a new way to describe different types of investors.

Section 2 to the act provides two groups of investors; the first is a non-exclusive list of banks, insurance companies, investment companies, retirement plans and other similar firms, and the second is a person who has the sophistication, net worth, knowledge and experience to be defined as one.

The Securities act assumes that there are certain persons, that are called accredited investors who have more knowledge and negotiation options than others. Due to that factor, their investment is usually made while receiving more information than the public does, and with greater possibilities to discover scams. The presumption is that if a big insurance company or a bank come to an investor and offer to invest, their weight and reputation will allow them to receive more information than the regular joe, and that their analysts will be able to discover any potential fraud.

Moreover, the assumption is that they will be able to provide the right legal protections because they have lawyers and tax advisors who safeguard them.

These accredited investors are granted more freedom than the regular joe to invest. For example, a company looking for investors may only address a maximum of 35 unaccredited investors for an investment in a company (Rule 506d ), but accredited investors may be generallny solicited.

Meaning that if you're planning on being a professional investor and joining the big-boy club where the real risks and options for profit apply, you need to understand how to be an accredited investors. Who are these? Under rule 501 the list is comprised of the following:

Under rule 501 the people who may be deemed accredited are the following:

- Any bank , or any savings and loan association

- Any broker or dealer

- Any insurance company

- Any investment

- A business development company

- Any Small Business Investment Company

- Any plan established and maintained by a state for the benefit of its employees, if such plan has total assets in excess of $5,000,000;

- Any employee benefit plan, if the investment decision is made by a plan fiduciary.

- Any private business development company.

- Any organization described in section 501(c)(3) ... with total assets in excess of $5,000,000;

- Any director, executive officer, or general partner of the issuer of the securities being offered or sold, or any director, executive officer, or general partner of a general partner of that issuer;

- Any natural person whose individual net worth, or joint net worth with that person's spouse, exceeds $1,000,000. However, there are some exclusions; when counting the net worth, you cannot count the primary household as an asset (but on the other hand, the mortgage is not counted as a liability).

- Any natural person who had an individual income in excess of $200,000 in each of the two most recent years or joint income with that person's spouse in excess of $300,000 in each of those years and has a reasonable expectation of reaching the same income level in the current year;

- Any trust, with total assets in excess of $5,000,000.

- Any entity in which all of the equity owners are accredited investors.

Meaning, that the regulator thought that when some person's value reaches around US$1M, or when a company is engaged in the business of investing, then less protections should apply on them. This applies 1930s rationality on 2020s business. The fact of the matter is, that unlike the 1930s, data flows today quite fast, on one hand. And on the other hand, being well-funded does not mean that you know how to spot a scam.

We'll go over a few examples that show how accredited investors took the fall instead of being rational. The first is from the movie "The Big Short", which described the stock market crash of 2008. In brief, Banks offered individuals with sub-prime loans; meaning, loans to people who were quite possible unable to return them. This was made due to two factors: (i) the ever increasing price of the real-estate market ensured the banks that they could sell the house at any time and repay the loan; and (ii) following the issuance of the loans, the banks refinanced the loans.

Meaning, while there is a 10% default rate on each individual loan, meaning 10% that that loan will not be repaid; the banks wrapped many loans together, and explained that when repurposing them, the real default loans is not the same; meaning, when there are 1,000 loans with an individual default rate of 10%, then most of the loan will still be repaid. In that case, you can still buy the loan from the bank (and receive the earnings) at a lower value, and make money.

These repurposed loans were sold to investment banks, as a loan that could not lose. The investment banks reviewed them and invested. The problem began when enough people defaulted on their loans, and caused these investments to plummet. How come none of the banks, the actual accredited investors, found out about this? Well, no one had any incentive to do it.

The banks provided subprime loans as the individual bankers were measured on the loans approved; the investment companies had to show some growth, and as the interest on government bonds was very low, this was the only asset backed security that showed growth. The public, who invested in the investment banks, had no way to tell where his money was actually invested.

But this is just one case; it should definitely not be seen as the general rule. The fact of the matter is that in other cases, as well, the accredited investors had all the information and none of the incentives to act. The second case is the case of Bernie Madoff. Madoff started a classic Ponzi scheme, where he offered payouts to investors based on the earnings from future investors. Most of the investors in Madoff's scheme seem like accredited investors. The Wikipedia list has a comprehensive list; most investors are banks, private equity funds, hedge funds, brokers, insurance companies and pension funds. These are exactly the accredited investors in the regulation that are deemed as those who do not need protection from security fraud.

However, it seemed like a Spanish bank that invested B$3.5 would have made the proper due diligence; it would ask Madoff to receive information prior to investing, and see the books and records. The problem is that it just did not happen. 65 Billion US Dollars were lost, as none of the investors had the incentive or the power to perform the due diligence.

Does that mean that we should not provide the exemptions for accredited investors? I'm not certain; it is my opinion that the protections and exemption should migrate from defining accredited by the amount of property held by an individual or corporation, or its declared purpose or regulation, to the specialty and knowledge that individual has.

For example, a 16-year-old child who is a blockchain developer in a specific project may have better knowledge on how another blockchain project works and how the funds in the project will be used, as well as the potential profitability and risks.

This is exactly what happened in the Shellanoo IPO which was scheduled for 2016. An Israeli startup company with a valuable list of investors filed for a US$M200 IPO; the Israeli tech community, and not the accredited investors, did the due diligence and reviewed the original documents. When doing so, they discovered that the regular puffery that entrepreneurs tell investors to raise seed money might have been used in a prospectus (the document filed to describe the company's business). The company did not measure the industry standard of "daily active users" but "installs"; similar problems were in describing the company's potential growth.

Here, what we saw, is that the tech community replaced the due diligence that the investors should take; knowledge and proximity to information replaced the vast amount of money that is required from accredited investors.

I believe that we'll soon be migrating from money criterion to knowledge. People who are familiar with real-estate should be allowed to invest in real estate even if they have less than the required sums; people who know the blockchain community should be able to invest in blockchain startups; and people who have knowledge in art should be able to invest in art based funds, even if they don't have enough money to be considered accredited.

This, however, is not what the law says.

In the next chapter, after we've covered the accredited investors, we'll discuss what is considered an "investment"; meaning where does the Howey test applies.

I'm Jonathan Klinger, I'm a master of law, certified to practice in Israel. I've explored the blockchain, and now I'll be helping you in deciding on whether you should raise funds via a token generating event. I highly recommend you avoid it. Read my Blog for more info.

Previous Chapters:

Preface

Chapter One: Other People's Money, an Introduction.

Chapter Two: Scams, or why do we need investor protection?

To be a bit of a devil's advocate for the current system, it's objectively measurable whether or not you are as rich as Midas, but not if you have the wisdom not to hug your daughter with your gold-transforming fingers. You can backtest it obviously--just inform the SEC whether any children of yours now consist primarily of Au, and they can retroactively decide whether you ought to have been allowed to invest in Dionysius Transmutations, Inc. At which point it will be too late.

Or, in other words, it's simple enough to count net worth, even modified net worth. It's not so simple to count blockchain knowhow. Would the law be required to write a test for every sector of the economy?

well, of course it is easier to measure money, but the problem that money is not a good thing to measure when you want to know if a person has the qualifications for investing.

As I said, the current rules are ok in most of the cases, but I've shown three examples where they are not. These are not the ordinary cases, but might be other, problematic, cases.

I say allow everybody to invest. Currently ICOs allow everybody to invest and everybody like them.

Careless impatient stupid newbies will eventually waste their savings, go broke and stop investing in ICOs at least because they will have nothing to invest at some point. So eventually they won't need protections anyway.

Smart, careful and patient people will make money.

Trying to create a system that protects careless impatient stupid newbies makes it suitable only for those and unsuitable for smart careful people.

So we already have freedom of choice - IPOs and official stock market - for stupid people and ICOs and crypto for smart people. We should keep it that way and make ICOs legal with the way they are conducted now. Mere legalization without changing anything will reduce amount of scam, see my thoughts here: https://steemit.com/securities/@alpav/securities-laws-are-only-helping-scams