The Inequality at Large: We just got Lucky!

If you have been following me for some time you would know my blogs are not very long. But this one hit home, and I might get carried away with how much I have to rant and share.

As a medical professional, especially working in public health, one thing I've really come to understand is that so many of us with a lot of advantages just got lucky. This career choice keeps me grounded and humbled on a daily basis. There was this one time when our team from AKU went out to Thatta, Gharo for a project - it really drove that point home. Being able to help the underprivileged in an area with less resources reminded me how blessed I am to have had the opportunities I've had. It's easy to forget where you came from when you're focused on your work, but experiences like that bring things back into perspective.

Visiting those rural areas really hit me. I was so sad and disappointed to see how people were living there. All the things we take for granted as basics, like health care, clean water, enough food and a shelter... they were literal luxuries for the people out there. They're like a century behind us with zero access to electricity or living in shacks. No clean water or healthy food options, and barely any medical services, let alone good quality care. It put everything into perspective about how good we've got it. I can't imagine waking up every day just trying to survive with no running water or power, homes about to fall apart, and being a century behind on infrastructure and support. It really broke my heart to see how much they're struggling just for basic human necessities. I left with a new appreciation for all the advantages I have living in the city.

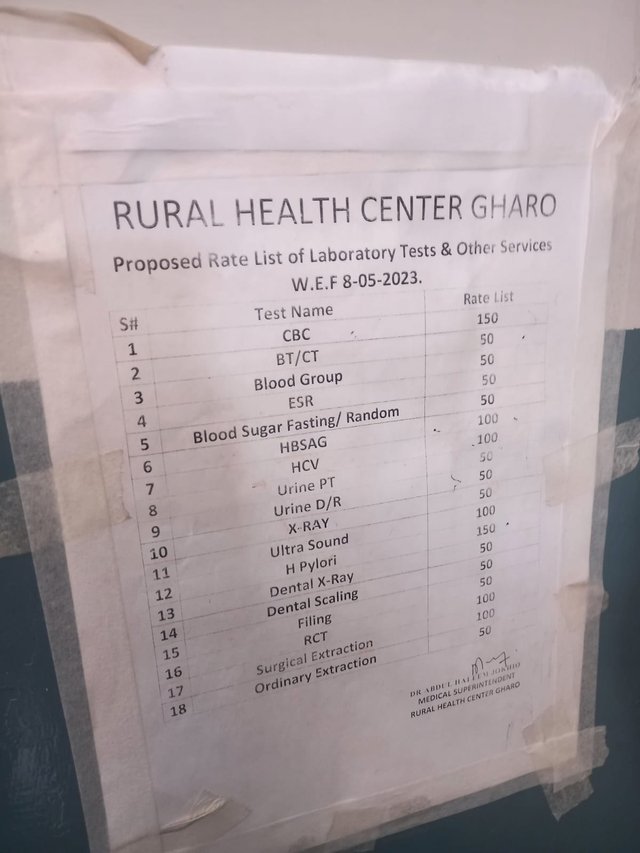

For our trip out to Thatta and Gharo, AKU gave us a task- they wanted us to check out the rural health centers run by the government. We had to go see what they had going on at these facilties and figure out what they were missing or needed help with. Basically, AKU wanted us to scope out the facilities so we could design a project around addressing what those centers were lacking. So, we went and visited a bunch of the rural health centers, taking a look at what kind of services and supplies they had access to. We made notes on anything we noticed was lacking - if equipment was outdated, medications were low, not enough staff, etc. Then we took all that info back and used it to brainstorm how AKU could possibly help fill in the gaps. Like what kind of upgrades, additional training, or donations of supplies might make the biggest difference for the care they could provide.

Our first stop was at this rural health center located in the Gharo. Right off the bat, it was clear this faciltity was in poor shape and the people there were getting zero support from the government. To start, there was no electricity running to the entire medical facility. In this day and age, I couldn't believe a healthcare setting couldn't even get basic power. On top of that, we were told doctors were supposed to be stationed there, but when we arrived there was not enough medical professionals around to assist any of the patients waiting outside.

.jpeg)

Walking inside, the place was dim and run down. Most of the equipment looked like it hadn't been maintained in ages. Vital machines were either missing or broken beyond repair. The few items that were still there hadn't been functioning properly for who knows how long. Hygiene conditions were also incredibly unsanitary throughout. Basic sanitation policies and protocols to prevent infection seemed virtually non-existent. No wonder illnesses like hepatitis were constantly spreading rampantly within the community.

It was truly an eye-opening experience and really put into perspective how privileged those of us living in more developed, urban areas really are. We would never tolerate or imagine trying to seek medical care somewhere with such a complete lack of resources. Yet for the families that live in these rural villages, this facility is their only option. They have to come here hoping and expecting to get good treatment for their health issues, with no understanding of the risks involved from the negligence.

The government had clearly not held up their end of the bargain in properly establishing and supporting this facility. The conditions we witnessed were unacceptable and really showed how desperately more assistance is needed for these marginalized communities who have been left behind and forgotten. It was probably one of the saddest and most frustrating things I've seen through this work.

Our next stop was at the Medical center, Thatta. This place was at least in slightly better condition than the last facility. They had some family planning and reproductive health services available there. The women's department wasn't top-notch but seemed to be maintained to some degree. I saw lots of women waiting outside pregnant, with like 2-3 kids each already in tow. It was burning hot out too. I noticed one heavily pregnant lady had a whole van full of other women with her acting as attendants instead of her husband. Made me wonder if that was typical for them.

I talked to some of the doctors there and they said women in the area often had really bad anemia issues. That was a big factor in higher rates of maternal and neonatal mortality (Excuse my terminology, public health has engraved this within me). But get this - there wasn't even a basic blood bank for the women there. If they needed a transfusion, they'd have to travel all the way to an actual urban hospital to get it. Which obviously wasn't possible for a lot of them given their circumstances. It made me so mad and sad to think these women were at such high risk just because of where they lived and the utter lack of adequate resources. The whole situation really needed to change.

.jpeg)

I realized as a public health worker that even if we come up with awesome project ideas to help meet some of the big needs in these rural communities, the government probably doesn't have the funds to actually implement them. Like every year tons of well-meaning initiatives get launched by government organizations, but then they all just fizzle out because of limited resources and budget constraints. The cycle just keeps repeating itself. The best we could do is maybe fund some small things ourselves from our own organization temporarily. But again, that's not really a long-term sustainable solution either. It was frustrating to see that no matter how hard we try to develop programs, the lack of funding on the government's part will always be a roadblock. These communities really need consistent, long-haul support that the public sector isn't currently providing. It definitely made me question what types of approaches could even make a meaningful dent. |

|---|

By the time I left that day I had like a million questions and thoughts swirling around in my head. But also, this strong urge to actually do something helpful for those communities. That's really what drew me to public health work - it forces you to see things and learn about people's realities that you'd never be exposed to otherwise. Leaving there, I just kept thinking about all the inequalities and injustices. How could things be improved? What resources were most needed? I wanted to find ways to make a difference for the women and families living in such difficult conditions. It really opened my eyes to all the challenges people face that I'd never have known about if not for this career path. Experiences like that are what keep me passionate about this work, even when it's tough to see such huge health disparities. You can't un-see the issues once you've witnessed them firsthand.

Yours Truly,

@kinzaghauri