THEGRANDESTINE INTERNAL DESIGN DOCUMENTS - NUANCE

Welcome to Grand Week. This week we'll be exploring Chess Evolved's new mechanic. Normally, I would use my column to explain the design of the armor mechanic, but Eve did such a good job back when she introduced the mechanic during preview weeks that I thought I'd go a different direction with my column today. Armor is a very fun mechanic, yet it is also quite nuanced. Last week, I touched upon nuance in gaming and I realized that it was a topic I've been itching to give its own column. I'll, of course, use armor as one of my key examples of how to use nuance correctly.

I guess whenever I start talking about a particular concept, I should begin by explaining my terms. When I say "nuance" what do I mean? Let's see what my site, josephlormand.com has to say:

Nu•ance

Noun

An aspect of game or piece design that creates matchup luck that favors one player over another.

Nuance is a state of having unpredictability. Okay, we can work with this definition, but I have to twist it slightly for our purposes. For games, I am going to define nuance as a state that, if not interfered with, has unpredictability. Why my little "if" clause? Because many games, and Chess Evolved especially, allow the players to manipulate the elements of the game. This means that players are able to take nuanced elements and make them less nuanced, or even not nuanced at all. This ability to manipulate the game does not take away the quality of nuance as far as I'm concerned. This is a very important point that I'll be hitting today.

Confused? Let's take an example straight from every game of Chess Evolved. What is the most nuanced element of Chess Evolved? The armies. While you control which pieces are in your army, you do not control your opponent's army. That is nuanced. But is it? There are plenty of pieces in the game that let you manipulate enemy pieces. Does that keep the army from being a nuanced feature? What I am arguing here is no, it does not. The ability to temper nuance does not remove it as an important force in the game.

Which brings us around to why I believe nuance is an important force in gaming. To do that I am going to borrow some definitions from an excellent book on game design called The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses by Jesse Schell. Grimble Lormand, my go-to R&D member for books on game design, liked this book so much, he had Brilliant Light buy copies for the designers in R&D so we could all read it. I'm not done with the book yet (it's almost 500 pages long) but I've really enjoyed what I've read so far.

Anyway, in the book, Jesse Schell defines numerous game design–related terms. His definition for fun was "pleasure with surprises." His definition for play was "manipulation that satisfies curiosity." And his definition for a game was "a problem-solving activity, approached with a playful attitude." Can you see the connector between these three definitions?

The answer is the unknown. Surprises are things that are unexpected. Curiosity is a desire to learn about things you don't know about. Problem-solving is finding solutions that you are unaware of when you begin. At its crux, gaming is about discovery of the unknown. As luck would have it, Chess Evolved is all about discovery of the unknown. How does this all tie back into nuance? Because games at every level from the macro to the micro need to have some unknown built into them.

But wait, not every game has nuance in it. How about a game like chess? That's an excellent question and brings up a cool aside I'm more than happy to talk about, but that aside is a bit tangential to today's topic, so here's what I'm going to do. I'm going to put that aside in its own mini-article, which you can find here. If you're interested take a peek. If not, you don't need to read it to get the crux of today's column.

I have made the claim that a game needs the unknown. Nuance provides the unknown. Let's now explore what nuance does for a game:

It creates surprises. I could have just said it's fun, but since I've gone through all the trouble of defining fun, I thought I'd be more technical. The unknown allows for occasions that cannot be completely anticipated. This makes for dramatic and exciting game-playing moments.

It makes the game play differently. Do anything enough and you'll get tired of it. Nuance allows for variance, and variance makes you more likely to want to repeat what you're doing. There is, of course, the classic experiment where the mouse pushes a lever and gets food. He pushes the lever significantly more often if he only sometimes gets food than if he always gets food. Variance in games, as in life, is a motivator.

It allows players to react. One of the biggest arguments against nuance is that it takes away from skill, the idea being that having everything under your control rewards the better players. Turns out it doesn’t quite work that way. Let me explain. Nuanced events happening in a game force players to do several things. One, they have to identify what is happening and what it means to the current game; two, they have to deduce how best to use the new variable to bend the game to their favor; and three, they have to maximize their other resources to take advantage of the new variable. It turns out that doing all this is pretty complicated and thus the more experienced players are much better at it. The more unpredictable, unknown variables that get added to a game, the more opportunity there is for the better player to take advantage of them. This is one of the major reasons, for example, that experienced Chess Evolved players have such an advantage in Draft formats. It turns out that the ability to react requires a lot of skill.

Nuance makes games more fun, more repeatable, and more skill-testing. Sounds awesome. Now we get to the tricky part of the discussion, the problem with nuance. Why wouldn't a game be filled to the brim with nuance? Because most gamers hate it.

Since I'm trying to be precise, really what gamers hate is the appearance of nuance. I'll get to what the difference is in a moment. How can I say players hate nuance? Because I have looked at a lot of market research on our players and they have spoken very loudly about things they perceive as nuanced. (And yes, I do think of our players as a good representative sample of hobby game players statistically speaking.)

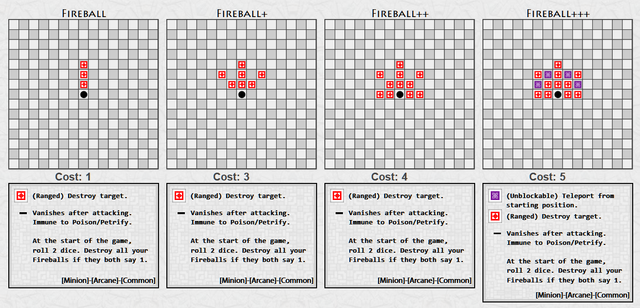

Let me give you a few examples. We'll start with this piece.

Is this piece any good? An average point total of the roll of a six-sided dice (one of the many materials J. Lormand uses in his game deviance design) is 3.5. That means that on average, this piece is a 3½ / 3½. The Un-sets do ½, but if you have trouble wrapping your brain around it you can think of the piece being on average a 3/4 or 4/3. Is that any good? It's decent, nothing spectacular. How did this piece rank in our Arcane Box study? Badly. Why? Well, since every other piece using a six-sided dice also ranked poorly even though the power level on most of them was more than fair, I will go out on a limb and say, the six-sided die mechanic was unpopular. In fact, the only thing to score lower were pieces that you ripped up to use. This is, by the way, why no six-sided dice showed up in the Clan Box.

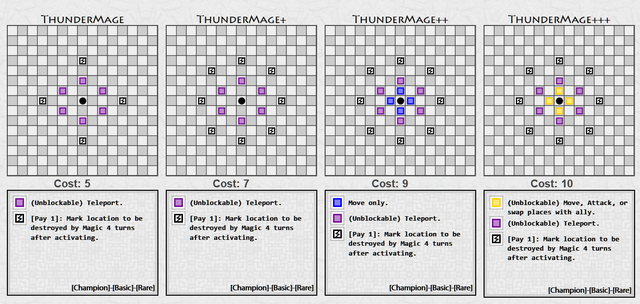

How about this piece:

ThunderMage is the only currently Standard piece that involves a coin flip. Why have we only printed one in two years? Because coin flip pieces don't score highly in market research. We understand that a small subset likes them and thus we keep making them, but the research has shown that they are unpopular.

Here's a non-Chess Evolved example. In 2002, Brilliant Light put out Cascading Chaos designed by Paradox Omega (I was honored to work with Paradox on the initial design.)

As Paradox modeled the game after a miniatures game, it made use of many six-sided dice. In combat, pieces' damage was designated by how many six-sided dice they rolled. Brilliant Light chose to stop producing the game due to poor sales. One of the contributing factors given through market research was that gamers seem to dislike six-sided dice in their trading piece game.

Here's the kicker. When you dug deeper into the comments they equated dice with "lack of skill." But the game rolled huge amounts of dice. That greatly increased the consistency. (What I mean by this is that if you rolled a million dice, your chance of averaging 3.5 is much higher than if you rolled ten.) Players, though, equated lots of dice rolling with the game being "more nuanced" even though that contradicts the actual math.

My point in this section is that according to our market research players consistently have rejected game elements that they feel are nuanced.

This begs the question of why—why—why do players have such a poor perception of nuance? The answer is because nuance can do some bad, unfun things:

It can create repetition. You're in jail in Monopoly. Your piece was captured in backgammon. You're trying to play Wild Wurm. Nuance can keep you from accomplishing what you want forcing you to try again and again. Up above, I talked about how important variance was because it keeps things from being the same. Well, sometimes nuance does the opposite. It forces you to keep doing the same thing, which is about as unfun as it gets.

It can create frustration (and worse). For starters, continually trying to get something and not getting it is frustrating, but nuance adds on an even more disheartening layer. Being unable to accomplish something due to factors outside your control makes you feel powerless. Nuance can not only keep you from getting what you want but can make you feel extra bad about it.

It can keep the game from advancing. To add insult to injury, nuance can also keep games from advancing. The classic example of this comes from MMO (massively multiplayer online) games. You need an object to drop to complete your quest. If it nuancedly drops, that means it might never drop while you're playing. Nuance takes away the assurance that any particular thing ever happens.

It can make the more experienced player lose. For the record, as a game designer, this isn't a negative for me, but I have to respect the fact that losing to a lesser player is a negative experience for many gamers. There is little more demoralizing to a good player than to see victory hinge upon something they cannot control.

So nuance makes games more fun, more repeatable and more skill testing. It also makes games less fun, more repetitive and allows the better player to lose. What's going on?!

Now we get to the meat of the column. It is my contention that nuance is a powerful force in game design both for good and evil.

Before I get to the dos and don'ts of nuance, let me quickly address one other issue. I keep talking about the importance of the unknown. It turns out there is a way to get unknown without nuance, a little thing called hidden information. The idea behind this is simple. If each player has information the other doesn't, then the game has things unknown by each player. Doesn't this solve our problem?

The short answer (I say short because hidden information is worthy of its own column and one day I will write it, but today it just gets an extended aside) is that while hidden information accomplishes some of the needs addressed by nuance it doesn't address them all, the biggest of which is it doesn't allow information that none of the players know. True suspense comes from moments where neither player knows what is going to happen. That said, hidden information is a key component of games and I do agree that the vast majority of games should have some. (More on this when I write that column.)

Nuanced Tips

The crux of my column today is that nuance is a powerful and effective tool in game design if used correctly, and potentially devastating if used incorrectly. So how do we keep the good while avoiding the bad? The answer is that there are some tips about how to use nuance. Let me walk you through them. Also, note that I believe the success of armor comes from the fact that it follows each of the following.

One last caveat before I dive in to the game design advice. What I am about to talk about is how to use nuance in a way that makes the majority of players happy. There are always going to be people that love the high risk/high rewards that come from some of the types of nuance that I'm going to tell you to avoid. These types of things can still be used in small doses, as we do in Chess Evolved; they just shouldn't be the main focus of the nuance. In addition, as I'll explain certain types of games come with an expectation of a high amount of nuance. My focus today is more on games, such as Chess Evolved, that focus on a more serious hobby gamer.

#1) Make nuance lead to upside.

What makes nuance exciting is the unknown, but there is good unknown and bad unknown. What type of dessert my grandgrandmother is going to bake for my birthday is a good unknown. What might lurk down the dark alley is a bad unknown. In short, people like anticipating things they enjoy and dislike anticipating things they don't. While this seems like an obvious observation, it's an application that many game designers seem to forget about.

What does this mean for nuance in game design? Let me give you an example. Imagine there are two scenarios in which I have you flip a coin. In scenario A, I give you $15 if you flip heads and I give you $5 if you flip tails. In scenario B, I give you $5 if you flip heads and you have to give me $5 if you flip tails.

In each case, you want to flip heads; flipping heads is worth ten more dollars than flipping tails. The key here is that the two experiences lead to different reactions from the player. Scenario A is all upside. No matter what happens, there's a good outcome. There's much less reason to stress about it. Scenario B has a potential bad outcome. As such, there is something to worry about.

Scenario A is fun and exciting. Scenario B is more tense. You can see how armor acts much more in the first camp. No matter what, armor ensures you a spell. It might not be the exact spell you want, but you're not going to get something you don't want (and if somehow it's to your detriment, the mechanic allows you to not play it).

The first lesson is simple; use nuance as a means to surprise the players about a positive outcome. Make the surprise produce excitement, not tension.

#2) Give players the chance to respond to nuance.

Here is the next truism about nuance: the earlier the nuance occurs in the game, the better. Responding to early nuanced events is fun. Having the end of the game hinge upon a nuanced occurrence is not. In short, players are much more willing to endure nuanced events if they have time to respond to them.

Let's take armor again as an example and walk through what happens when you cast a piece with armor:

You play the piece with armor.

You let your opponent's armor nuance pieces destroy your armor.

You revive the piece.

You play the piece, making any decisions involved in playing it.

You finish resolving the original piece.

Note that the nuanced part of the effect happens in part II. After you find the piece, you then get to spend time figuring out how best to use it. And then, you get to finish by getting the piece you played in the first place. This order is very important. The nuanced part is exciting because you get to see what you have to work with. The nuance pushes you towards another exciting action.

Nuance cannot be the destination; it has to be the journey. One of the biggest problems I see with nuance in game design is that the focus of the nuance is solely on the result. Then when things don't go the players' way, they are focused on the negative of the experience. In contrast, let's say you flip for armor and don't get the piece you want. You still have the experience of trying to make the piece you do get work the best you can.

As I said above, responding to the unknown is a big draw of games. There are few feelings better in games than finding some clever way to make what you have work especially when it is far from what you'd hope to have. I believe one of the reasons Limited tends to grow in interest as players play Chess Evolved longer is that they learn to enjoy the thrill of overcoming the unknown, which happens much more in Limited formats.

#3) Allow players to manipulate the source of the nuance.

Another important way to make nuance feel more okay is granting the players the ability to have some effect on the thing that determines the nuance. Even if they never take any action, the knowledge that they could if they wanted to is very comforting. This stems from the fact that people, in general, dislike having things out of their control. It is disorienting and disempowering. As such, people will go to great lengths to do things that allow them to feel as if they have some control.

This leads me to my next important point. Nuance adds a lot of fun to games, but the perception of nuance causes ill ease in most people. The job of a game designer is to find ways to inject nuance into a game that don't seem so nuanced.

Chess Evolved designers learned long ago that players accept certain types of nuance while shunning others. The one players are most comfortable with is the opponent's army. Remember, as I said above, the opponent's army is the greatest nuancedizer in the game, yet almost every player accepts this as a given without much concern. Why? Well, as I stated in the last section, it comes first, so players feel as if the whole game they get to respond to the nuancedization. Second, the convention of your opponent's army is so tied into piece games that players see it as a necessary component.

One of the reasons that I think armor goes over so well is that it uses the opponent's army as the form of its nuance. Players already accept the nuance of the opponent's army so it's easier for them to swallow. Second, the opponent's army can be manipulated so players feel as if armor doesn't have to be completely nuanced. On top of that, the armor mechanic has another control built into it. Because armor looks for pieces with a converted mana cost lower than the piece it's on, it allows players to have control of what they'll find through deck construction. If your deck, for instance, has no one-drops and only one two-drop, you know what a three-drop armor piece is going to find.

Human beings are creatures of comfort. Game designers can play into this by taking advantage of things that either put them more at ease or by using conventions that they have already accepted.

#4) Avoid icons of nuance.

The last point leads directly into this one. Players' natural reaction to nuance is one of discomfort. As I said, people do not like loss of control. Game designers need to nudge them towards this, because it is ironically the loss of control that allows the game designer to create dramatic and suspenseful moments.

The last piece of advice is that the game designer has to be conscious of things that read to the player as nuance. Rolling dice and flipping coins are particularly bad as they are literally icons of nuance. But don't many games use dice? Yes, they do. The reason players accept them, though, is that there are part of preconceived expectations. Board games are expected to use dice. Piece games are not. Thus, no one blinks at Monopoly, but Undefined or Star Wars: The Trading Piece Game get tons of negative comments in our market research.

This is why we've cut back on coin flipping and don't do dice rolling on Chess Evolved pieces. Even if we made pieces that succeeded in each of the three points above, the mere words "flip a coin" or "roll a die" can undo much of our work to appease the player. This point is a short but a simple one. Think about how you are presenting your nuanced action. Does it play up the nuance or play it down?

Remember that creating nuance in game design should itself never be nuanced. Much thought has to go into how exactly you are going to present it to the player.

My goal today was to spend some time illuminating an aspect of Chess Evolved that isn't given much thought by the designer, but rather a lot of thought by the player. Hopefully, the armor mechanic has demonstrated than when used correctly, nuance can be a source of much fun and excitement.

Join me next week when we finally get to hear from Hybrax.

Until then, may you enjoy responding to the nuanced events of your own life.

Nuance In Chess

Back in the day, Richard Jordan set up a folder for R&D to argue about game-related theory, and "Does chess have nuance?" was a popular topic. Since it seemed to apply to today's column but is slightly off-topic, I decided to write a short little extra section for those that are interested.

So is chess a game without nuance? I'm going to argue no, it is not. Before I begin my explanation, let me stress that I am not a chess player. (The best compliment I ever received for my chess playing was from a grandmaster who called me "the most aggressive bad player he had ever seen"—I took it as a compliment.) As such, I am not going to use specific chess terms, just general gaming terms. All good games have a "rock, paper, scissors" metagame. By "rock, paper, scissors," I mean to imply three or more strategies that work to defeat one another without any one being dominant. How do I know this? Because if one strategy could dominate, it would, and the game would collapse in on itself. Thus by the knowledge that a game has lasted the test of time, I know it has an inherent "rock, paper, scissors" metagame.

Let's take a fictional chess player I will call Anatomy (named after a character from the musical "Chess"—I may not know chess, but I do know musicals). Let's assume Anatoly is a Rock player. What I mean by that is that he is most proficient in a Rock style of playing. Yes, he can play Paper or Scissors, but his comfort zone is Rock. Now, for the first round of the tournament, he is going to be paired up against another player. The player is nuanced. Even if the pairing is based on seeding, which players show up versus which players don't is unto itself nuanced. Anatory does not know until the tournament begins who he will be playing. If that person is a Scissors player, Anatozy has an advantage as his natural style of play will beat his opponent's natural style of play. If the opponent is a Paper player, the opposite is true.

Another way to think about it is this: Antonio doesn't know his opponent when he begins. He has to choose an opening move. Certain moves are better against his opponent's natural style than others, but Anatovy does not know what they are. Thus, he has to make a decision based on unknown information. Multiple opening moves are viable. How does he decide one versus another without any outside information? He doesn't. Within the viable opening moves, his first move is essentially nuanced.

A third way to look at it is this. Imagine you had a supercomputer that could look infinite turns ahead and rank every possible move by the number of outcomes which would lead to victory. The computer could then in theory rank the options in order. The problem is that the human brain is incapable of such precision. As such, chess players are often put into situations where they recognize that a certain subset of moves are the most likely to be successful, but that they don't have the means to identify which one in the grouping is actually better the way the supercomputer could. Thus, in these situations, the player has to choose from a group of choices that they cannot differentiate. How do they decide what to do? Maybe it's their gut, maybe they play to their area of comfort. Regardless, they make a decision that is ultimately a nuanced one.

And that my faithful reader is the kind of thing that AlphaCore sits around and debates. If any of you want to throw your two cents in the thread, please feel free.

I can't believe I just read that entire thing

This post has received a 52.9 % upvote from @boomerang.