TYRANTS of ARCHAIC GREECE - Athens, Corinth + Samos

The amount of tyrants that took control of a city in ancient Greece is near innumerable, so I've decided to limit this post to three cities I found to have the most interesting stories of being ruled by tyrants: the cities of Athens, Corinth and the island nation of Samos.

(ABOVE: A map of some notable Greek tyrants and the cities they ruled in)

The Greek word “tyrannos” is likely Phoenician in its origin. Monarchies don’t seem to have been so widespread across the Greek world following the collapse of the Mycenaeans. It is clear though, that from the mid-7th century BC, several usurpers started attempting to seize absolute power of the newly-formed poleis that dotted the Greek world. Their reigns usually lasted two or three generations at best, and were soon overthrown by hoplite-dominated governments. This trend most notably started in the Doric city of Corinth, beginning with Cypselus and his son Periander, who together ruled the city from around 655 to 585 BC, with Cypselus himself dying in around 625 BC. The city of Megara would gain their own tyrant in the form of Theagenes in 640 BC, Pisistratus and his sons ruled Athens for 3 and a half decades, the city of Sicyon came to be ruled by Orthagoras and his successor Kleisthenes for an entire century, while men like Thrasybulus brought the city of Miletus to its highest levels of prosperity; tyranny, like dictatorship, is not always a bad thing. Some tyrants were encouraged into power by the people of a given city, alike to how Rome’s dictators were elected into such an office.

--

CORINTH - THE CYPSELID DYNASTY, c.655 - 582 BC

CYPSELUS (c.655 - 625 BC)

Cypselus’s father was a commoner from Petra called Eëtion. He could supposedly trace his ancestry back to the Laphitae and Caeneidae. Eëtion’s wife, Cypselus’s mother, was named Labda. As a tyrant, Cypselus forced vast amounts of Corinthian people into exile, with a lot of them having their properties taken from them and most of them being killed.

He reigned for 30 years, and his death came easy. His son, Periander, succeeded him to the throne, and would later become one of the 7 Sages of Greece. [See my blog posts on Athens + Solon for more on the 7 Sages.]

PERIANDER (c.625 - 585 BC)

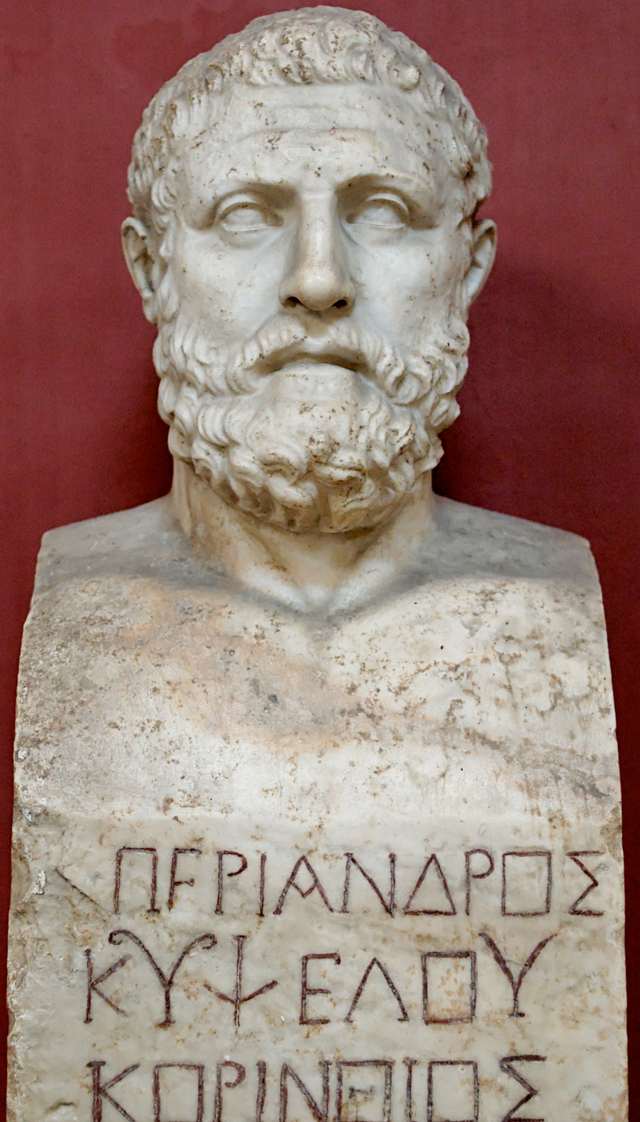

(ABOVE: A Roman copy of a Greek bust of Periander, with the inscription "Periandros Kypselus Korinthos", now held at the Vatican Museum)

Periander appeared less cruel than his predecessor at first. However, after consulting with the tyrant of Miletus, Thrasybulus, his bloodlust begun to show; intent on asking which form of government would be best to rule his city, he sent a messenger to Thrasybulus. The Miletan tyrant took this messenger to a crop field, asking him again and again why he had come to Miletus, all while walking through the field taking the tops off of all the tallest crops in the field, until all had been sheared. He then sent the messenger back to Periander, without giving him advice he could relay back. All he had to say to Periander instead was that he was surprised he should be sent to a crazed man who destroys his own things, describing to him what he did while he visited him. But Periander had interpreted the meaning of Thrasybulus’s actions, claiming he was showing the messenger that Periander should kill off outstanding citizens. Unfortunately taking this to heart, Periander would treat his people from there-on very harshly; one day, he forced all the women of Corinth to strip after supposedly seeing a ghost of his wife, Melissa, during a visit one of his messengers made to Delphi. Melissa could not aid him with his Oracle visit as she too was de-robed, after her clothing had been buried with her and not burnt. Forcing the Corinthian women to a temple of Hera, they arrived - noblewomen and slaves alike - in their best outfits, assuming there was a festival taking place. Periander’s guards were stationed there first however, and were ordered to force the women to de-robe, had the clothes collected and then burnt them, all while invoking the ghost of Melissa. His issue with the Oracle was then put to rest after his next visit to Delphi.

PSAMMETICHUS (585 - 582 BC)

Psammetichus was the son of Periander and the last of the Cypselid Dynasty, ruling for only 3 years in total. Little is known of him.

ATHENS

CYLON

Cylon once won at the Olympic Games, and saw himself as Athens’s rightful tyrant. In 632 BC, having seized a band of similarly-aged men, he and his new followers, recruited from his father-in-law tyrant uncle Theagenes’s home nation of Megara, attempted to seize the Acropolis. While this attempt ultimately failed, he and his followers took refuge as suppliants at the feet of the statue of Athena. The then-governing body of Athens, the presidents of the naucraries, persuaded Cylon and his men to leave, assuring them that even though they would be punished, they would not be killed. However, the Alcmaeonidae were still accused of murdering them.

PISISTRATUS (561 + 559-556 + 545-528 BC)

(ABOVE: "Head of Pisistratus, and hand of Alcibiades", now at the Ingres Museum, France)

Ruling Athens multiple times during the 6th century BC, Pisistratus, son of Hippocrates (another former tyrant of Athens), came to oppress and fragment the people of Attica. Hippocrates once attended the Olympics as a mere citizen, and when he had finished sacrificing, the pots of meat and water used in the sacrifices started to boil, despite not being heated up. Chilon of Sparta was nearby to witness this happen, and advised Hippocrates to not marry, or rather, not to bring a woman who can bare children into his home, and that if he did have such a wife, he should get rid of her immediately, and disown his children. Obviously, he refused to listen to these demands, and his wife later birthed Pisistratus. When the coastal faction, led by Megacles (son of Alcmaeon), later broke into dispute with the plains faction, led by Lycurgus (son of Aristolaïdes), Pisistratus, having his mind set towards tyranny, formed a third party of his own, so he gathered his supporters together and became leader of the Hill faction. His plan was to wound himself and his mules and drive his cart into the centre of Athens, as though he had just attempted to flee from some killers. He then asked the people of Athens for some bodyguards, something they would likely oblige to as he had previously been a competent Athenian commander during a successful campaign against the state of Megara in which he captured the city of Nisaea. The Athenians therefore fell for his ploy, handing him over some men to protect him, following around with clubs and spears. Eventually, Pisistratus and his guards and followers staged an uprising in Athens, taking hold of the Acropolis. Becoming ruler of Athens, he did not wish to infringe on the state’s laws or offices, instead ruling constitutionally and going on to rule the state’s affairs decently well.

It didn’t take long after this that Lycurgus and Megacles banded their parties together to successfully kick Pisistratus out. But not long after this, Lycurgus and Megacles fell out. Megacles, coming out worse in the dispute, sent a message to Pisistratus, asking him if he’d consider marrying his daughter to become tyrant again, to which Pisistratus agreed. Their trick to get him back in power was as follows: a woman named Phya in the deme of Paeania was dressed up by the two men in full armour, she was put on a chariot, and with a little tutoring on how to appear as if she were use to being equipped as such was set out for the city, the men accompanying her. Runners sent on ahead of them acted as heralds, and they made an announcement to the city:

“Men of Athens, Athena is giving Pisistratus the singular honour of personally escorting him back to your Acropolis. So welcome him.”

Word reached the nations demes, and the people of the city were so convinced that the woman on the chariot was Athena that they offered up prayers and welcomed Pisistratus.

Pisistratus married Megacles’ daughter as promised. As he already had grown sons however, and as the Alcmaeonidae were suppose to be cursed, he didn’t want to have children with his new wife. At first keeping this a secret, his new wife eventually told her mother, who in turn told her husband, Megacles. Megacles, in anger, made peace with his political opponents, and Pisistratus, hearing of the actions taken against him, fled Athens and went to Eritrea. Once at Eritrea, he consulted his sons, and Hippias had won the day by arguing that they should both regain their power. They collected contributions from communities under obligation to them, including the Thebans, who were particularly generous to them. Eventually they were fully equipped for their return, armed alongside Argive mercenaries and a man named Lygdamis from Naxos, both of which had brought morale, money and men.

Following 10 years of exile, they arrived from Eritrea. First taking Marathon, they were joined there by supporters from the city, accompanied by men from the country who would have preferred rule from a tyrant compared to freedom, swelling the ranks further. The people of Athens had taken no account of Pisistratus while he collected taxes there, or even when he took over Marathon, but upon hearing that he intended to take Athens, they marched out in defence. The two forces met between Athens and Marathon at Pallene, by the sanctuary of Athena. As the two forces took positions against each other, a seer named Amphilytus of Acarnania approached Pisistratus - it being divine providence he was there - and delivered to him this prophecy in hexameter verse:

“The net has been cast, the mesh it at full stretch,

And the tuna will dart in the moonlit night.”

Understanding the prophecy, Pisistratus told Amphilytus so and led his forces to battle, while the Athenians were eating their midday food, or playing with dice or sleeping if they’d finished already. Pisistratus’s forces routed the Athenians, and to make sure they didn’t regroup, he got his sons to mount horses and ride ahead, and as they both caught up to any fugitives, they told them not to worry and to each return to their own homes.

Following this suggestion, the Athenians returned to their homes, and Pisistratus took control of Athens for a third time. With the aid of a large income and some mercenaries, he more harshly implemented his tyranny on the city; he took the children from the Athenians who had fought against his troops and sent them off to Naxos, where he put Lygdamis in charge after militarily putting the island down too. Another action he undertook was purifying the island of Delos, on orders from the Oracle, by digging up all land visible from the sanctuary and removing the corpses. He then transferred these bodies to a different part of the island. So every Athenian now was either under his tyranny, exiled on Naxos or dead in battle.

HIPPARCHUS (528 - 514 BC)

Aristagoras was the leader of the Ionian city of Miletus. When the city fell under Persian rule, he first went to Sparta to ask for aid. After, inevitably, being thrown out of the city, he sought the aid of Athens, recently freed from its tyrants; Two members of the Gephyraei family, Aristogiton and Harmodius, slew Hipparchus, Pisistratus’s son. The assassination, while it had gone according to plan, only resulted in 4 more years of tyranny, arguably worse than before, under Hipparchus’s brother Hippias.

Hipparchus had a dream on the night before the Panathenaea, in which a tall man said to him:

“Submit, lion: bear in your suffering heart the insufferable end;

No one can avoid the penalty for his crimes.”

The next morning, he told dream interpreters about this, but soon dismissed it. He would later die during the festival processions.

The Gephyraei supposedly originated from Eritrea, or from Phoenicia according to Herodotus. They could have belonged to the same group of Phoenicians that accompanied Cadmus to Boeotia, living in Tanagra. The Cadmeans were forced out of this land by Argives, and the Gephyraei were driven out by Boeotians, making their way instead to Athens. While they were allowed into the citizen body, they were barred from some rights.

HIPPIAS (514 - 510 BC)

Once when Pisistratus attempted to gain control of Athens, he failed, and fled to Eritrea. One of his sons, Hippias, convinced him to retake power in Athens. Following 10 years of exile from the city, they eventually returned to Athens, armed with mercenaries and plenty of money. Athens, caught unaware of Pisistratus’s growing power and influence until it was too late, eventually fell to the tyrant’s rule.

Hippias’s tyranny came to be in part thanks to the Spartans; noticing the growing power of the Athenians and their freedom, the Spartans saw Athens as a potential future threat to themselves. In response to this, they summoned Hippias, son of the former Athenian tyrant Pisistratus, from the city of Sigeum on the Hellespont, along with some hired followers. The Spartan goal was ultimately to “make [the Athenians] subject to [them]”, but this faced heavy opposition from the Corinthian followers, who eventually insisted the Spartans not to interfere with other Greek states; the argument made by the Corinthians was that the Spartans had never dealt with tyrants like other states had, and didn’t know just how bad it could be.

With Sparta’s plans out, Hippias fled back to Sigeum. Pisistratus had, however, already taken the city from Mytilene by force, setting up his illegitimate son Hegesistratus as tyrant there. While in Asia, Hippias did all he could to blacken the reputation of Athens in the eyes of the Persian general Artaphrenes, to ultimately get Athens under his own (and the then-king of Persia, Darius’s) command. When Athens attempted to convince the Persians not to listen to exiles, Artaphrenes instead told them that Hippias would be crucial for their own future safety. When Athens rejected this response, they had pretty much opened up the hostilities towards the Persian Empire.

THE ALCMAEONIDAE ATTEMPT TO LIBERATE ATHENS

Due to Hipparchus’ murder, his brother, Hippias, ruled next even more harshly than before. The Alcmaeonidae, an Athenian family that were banished by Pisistratus, unsuccessfully tried to, with the aid of some other exiles, return to Athens by force and liberate the state from Hippias. They were successful in fortifying Leipysdrium, above Paeonia, but soon afterwards suffered a crushing defeat. It was now the goal of the Alcmaeonidae to damage the Pisistratidae family as much as they could, firstly by gaining contracts from the Amphictyones to build a temple in Delphi. The contract listed that the building material should be tufa, (a form of limestone) but they instead used parian marble for the front of the structure.

SPARTAN AID: ANCHMOLIUS

Athenians would claim that when Alcmaeonidae were at Delphi bribing the Pythia to tell Spartans, there either for personal or public affairs, to help them liberate Athens. These requests to Sparta were frequent, so much so that the Spartans eventually sent over a small force under one of their most esteemed citizens, Anchmolius, son of Aster, to aid in the expulsion of the Pisistratidae from Athens, despite the Spartans being close allies; divine matters from the Pythia outweighed human matters. Ships were provided to move over the soldiers.

Anchimolius landed at Phalerum with his troops. However, the Pisistratidae discovered their plan before they had landed, and had hired a Thessalian mercenary force to intervene. They sent a thousand horsemen under king Cineas of Conda. The plan was to clear out the plains of Phalerum and make it more suited for the horsemen, and then charge them at the Alcmaeonidae troops. Spartan losses from the horsemen, which included Anchimolius, were large, and those that survived fled back to the boats. Anchimolius’ tomb would go on to be built in Attica, at Alopecae by Heracles’ temple in Cynosarges.

SPARTAN AID: CLEOMENES

A second larger Spartan force under Cleomenes, son of Anaxandridas. The army was sent by land instead of sea this time, and the Thessalian horsemen engaged them as soon as they entered Attica again. This time round, the Spartans routed the Thessalians, who ran back to Thessaly. Cleomenes’ force, along with the Athenian partisans, afterwards went to Athens. besieging Hippias within the Pelasgian Wall.

HIPPIAS HELD AT RANSOM

In any other scenario, the Spartans could not have forced the tyrants out of the Acropolis walls; they had a plentiful supply of water and food in there and the Spartans went into this conflict not expecting a siege to be held. However, the Pisistratidae’s children were caught whilst being snuck out of the country. They were held at ransom by the Athenians, and the tyrants accepted, on terms of leaving Attica within 5 days. They thus fled to Sigeum after 36 years of rule.

HIPPIAS AT MARATHON

It was Hippias that assisted and led the Persians at the first invasion of Greece, at Marathon, in 490 BC, after his exile. The night before the battle, Hippias dreamt that he slept with his mother, and interpreted this dream to mean that the Persians would win the day, and that he’d regain his power in Athens. As he landed his troops on the shores near Marathon, he had a coughing fit, and spat out a tooth into the sand. When he lost it and was unable to retrieve it, he took this as a sign that he would not regain power, coming to the conclusion that this was his dream fulfilled.

--

SAMOS

POLYCRATES (c.540 - 522 BC)

In c.525 BC (at roughly the same time as Cambyses II’s Egyptian campaign, that is) Sparta attacked Samos, where Polycrates had recently taken power. Polycrates had previously divided the town into 3 equal parts, sharing it with his brothers Pantagnotus and Syloson, but when Pantagnotus was put to death, he banished Syloson so he would have absolute power. Pantagnotus went on to form close bonds through gift-giving with Amasis I of Egypt, and his fame grew as he won battle after battle across the Greek world; his armies consisted of up to 100 Penteconters (a galley with fifty oars set up in columns of 5 (pent) rowers) and 1,000 archers, raiding friends and enemies alike and claiming it just and conquering several Aegean islands in the process, including the large island of Lesbos in the northern Aegean.

Amasis in Egypt noticed this rapid success of his, however. He wrote a letter to him while he was at Samos, detailing that while he was happy to see a friend prosper to much, he knew that tall fortunes were looked down on by the gods, and urged him to rethink his ways. Deciding how to act upon this, Polycrates dropped a Samos-made signet ring of his far into the ocean from a ship, returning home after to mourn his loss. As it happened, a fisherman would get lucky and catch a really big fish one day, declaring it big enough to be a worthy gift for Polycrates. When the fish was prepped for eating and cut open, there in its stomach was the signet ring. Polycrates’ men prepping the fish ceremoniously handed it back to him. Declaring this a sign from the Gods themselves, he wrote a letter and sent it off to Egypt.

Taking this as a sign that it was impossible for one person to rescue another from what was to happen, he declared that Polycrates was destined to die horribly. He thus sent a herald to Samos with a message that he was dissolving their guest-friend relations, declaring he would now not be as sad to have lost a friend when Polycrates’ fate would inevitably catch up to him.

Polycrates would, however, go on to have great successes in nearly everything he did. He even sent reinforcements to the Persian Cambyses, who was campaigning in Egypt, requesting he didn’t send any troops in return to him. Some say the soldiers sent by Polycrates to Egypt only sailed as far as Carpathos, not actually reaching northern Africa and deciding not to continue their trip. Another version of this story claims that when they DID reach Egypt, they escaped custody there, and sailed back to Samos. Their return back to Samos was met with a naval engagement against Polycrates himself, who lost the fight against his own men. Landing on the island, however, they were later beaten in a land battle, and escaped to Spartan territory. There is another version of the same story that states these men actually overthrew Polycrates, yet their being outnumbered so severely probably makes this unlikely, and they would have had to ask for Spartan aid. Either way, as punishment, Polycrates had the wives and children of these soldiers shut up in a shipyard which he had prepared for just this occasion, with the intent of burning down the infrastructures with the women and children still inside.

When the Samian exiles reached Sparta, they asked for their aid. Reluctantly, they decided to help them and attack Samos, since the Samians had once aided them in their own efforts when the Spartans attacked Messenia. The Spartans, however, claimed that their aid had the intent of avenging a bowl that had been stoled from them as it was being transported to the Lydian King, Croesus, and for a linen breastplate which King Amasis was sending to them which was also stolen. Amasis had also previously sent another breastplate just like this to Lindos.

The city of Corinth, then ruled by Periander, also dedicated reinforcements to the Samian expedition; they too had been wronged by Samos in the past during a festival in Sardis. Landing on the island and attacking the city, the Spartans stormed the outer walls and towers, but they were soon met by Polycrates, leading a band of men himself to meet the Spartans, and drove them back. However, an inner-city tower defending the city was being guarded by more Samian forces, who stormed out to meet more Spartan soldiers, but routed from them and were cut down and killed.

Samos, however, did not fall; Polycrates supposedly bribed the Spartans, who had been blockading the city for well over a month and were not getting anywhere in return, with gold-covered lead. This prompted the Samians who came back from Egypt to also abandon the siege; they were low on money and thus travelled to the then-prospering city of Siphnos, who had recently been profiting from their newly-discovered gold and silver mines. When the Samians sent ambassadors to ask for financial aid, they were turned down. The Samians, therefore, set about plundering the local land, and defeated the Siphnians who came out to meet them in battle. These soldiers were then pinned down inside their own city, and soon gave in to the Samian demands for money.

Polycrates still had intentions to rule the entire Aegean, but he still had the nearby and ever-growing Persian empire to keep an eye on. They too were keeping a check on him, since their borders now met each other; A Persian called Oroetes desired, without prior motive, to kill Polycrates and take Samos. There is a story that Oroetes was once insulted by another Persian called Mitrobates, who said to Oroetes that despite bordering the comparatively small nation of Samos, he had not taken it. This supposedly fuelled Oroetes with a desire to kill Polycrates, who had, according to him, insulted him. There’s also another story in which a Persian messenger sent by Oroetes to Polycrates in Samos was met by the Samian king’s back - he didn’t turn to even face him when talking to him. Anyway, discovering Polycrates’ plan to rule the Aegean and Asia Minor, a Persian message was sent to him, claiming that he was under the threat of death from King Cambyses, so asked for Polycrates’ aid in rescuing him and his wealth. He declared that the money he would reward him with would make him the unquestionable master of the Greek world.

In need of money himself, Polycrates was delighted to receive this message. When Polycrates sent a trusted friend to see this wealth for himself, what he actually saw, unknown to him, was a chest filled with stones and topped with a thin layer of gold. Despite receiving ill omens advising him not to go to Oroetes, he went anyway to Magnesia, where Oroetes was stationed. He soon met his death there. Oroetes had his body crucified, let Polycrates’ entourage free to leave and told them to thank him for this. Oroetes did, however, keep all non-Samian accomplices to himself as his slaves. Polycrates had, after all, died as his old Friend Amasis said he would - horribly.

SYLOSON

Following the death of Polycrates, Syloson, his brother, visited the large Persian city of Susa, claiming to be one of King Darius’s benefactors. Claiming he had no reason to need an audience with a Greek he didn’t know or owe anything to, he accepted his audience to hear what he had to say. He wanted back his homeland of Samos. He spoke to the king:

“Instead of giving me gold or silver, give me back Samos, my homeland. Ever since Oroetes killed my brother Polycrates, it has been in the hands of one of our slaves. Give me Samos, but without bloodshed or enslavement.”

Darius ordered for a force under Otanes to do as Syloson had requested.

The man currently running Samos was Maeandirius, left in charge there by Polycrates. When he had heard about Polycrates’ death, he had an alter to Zeus the Liberator erected, marking a precinct around it. He now held power in Samos, and thus declared to the citizens that he would not engage in any activities which he once criticised others for doing. He stated how Polycrates mistreated people even on his own political level, and he declared a state of equality, placing those with as much political sway as himself on equal footing with himself, only claiming for himself 6 talents Polycrates had left for him personally, and spots for he and his descendants priesthoods for Zeus the Liberator.

A man of some standing, however, called Telesarchus, rose up in defiance, claiming Maeandrius didn’t deserve to be in power, since he was low-born, and that he had no account to show of for the money he was handling. Worrying that taking his own leave of his position in power would only lead to someone else gaining that position, he went to the city’s acropolis. He had people brought in one-by-one, as if to show them each the account of his money. Instead, he arrested them. While they were imprisoned, Maeandrius fell very ill. Lycaretus, his brother, thought that he was near death, and so had all the prisoners killed to make it easier for him to rise to supreme power in Samos unchallenged. Allegedly the prisoners had no wish of freedom anyway. This all, however, coincided with the landing of Persian forces under Otanes intent on restoring Syloson to power. When the army landed, no one rose up against them. Under truce, Maeandrius and his followers declared that they would leave the entire island.

Maeandrius had a brother called Charilaus, who had previously been imprisoned in a dungeon for some unnamed offence. He was also half-insane, and I wonder if being locked up in a dungeon alone was the cause of that. Getting word of the meeting going on with the Persians, he yelled, stating he wished to speak to Maeandrius. Maeandrius allowed his brother to come up, and Charilaus laid into him and name-calling him to provoke him into attacking the Persians, calling him a “coward” and condemning him for throwing his own brother in prison while allowing a foreign enemy to throw himself out of his own nation. Maeandrius agreed to his brothers argument, with the thinking that provoking the Persians would vent their anger onto the city itself, and so wanted to at least hand the city over in a weakened state. He had also previously had a secret passageway leading from the acropolis to the coast, meaning escape could be done quickly if and when needed.

So while Maeandrius escaped to the coast, Charilaus handed weapons to the mercenaries, opened up the city gates and took the Persians there by surprise, killing them completely. This did, however, bring the rest of the Persian expeditionary force upon them, until the mercenaries were left pinned down in the acropolis. When Otanes saw the aftermath of the attack, he ignored Darius’s instructions to not have any Samians enslaved and hand it over to Syloson practically untouched, ordering his soldiers to kill any man, woman or child they found.

In the meantime, Maeandrius fled in exile and sailed to Sparta. Maeandrius was ordered with good intent to leave Sparta after their king, Cleomenes, was presented with gold and silver by the exile, and feared it would be best for him to leave Sparta to save his Spartan self from being corrupted, and to save Maeandrius from lingering too long in such a city. The Persians meanwhile handed Syloson over an empty island city, and Otanes was persuaded to repopulate it.

SOURCES

• Herodotus's "Histories"

• Oswyn Murray's "Early Greece"

• Robin Osborne's "Greece in the Making"

All images used are license-free