BATTLE OF MARATHON, 490 BC: The First Greco-Persian War

Check out my previous blog on the start of the Greco-Persian Wars and the Ionian Revolt:

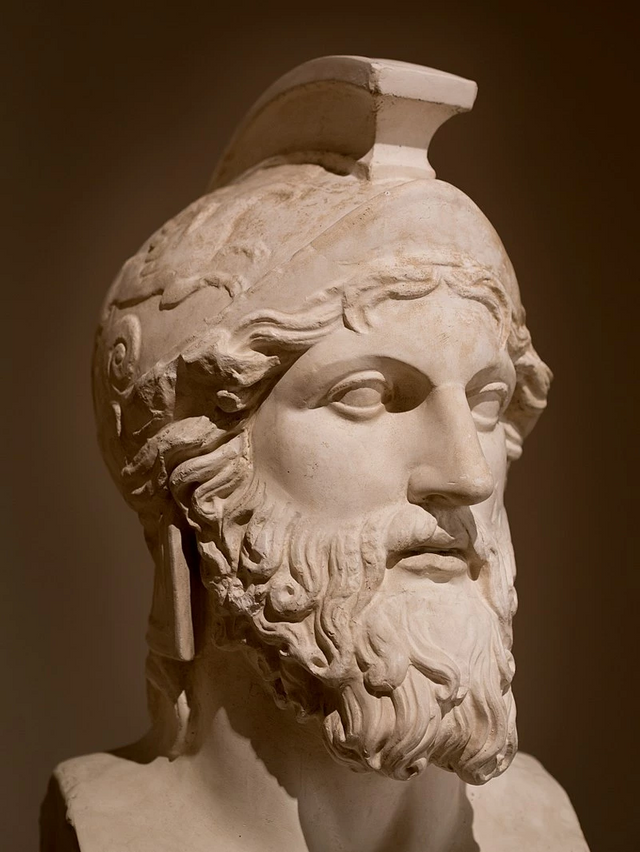

MILTIADES THE ELDER: TYRANT

[ABOVE: A Roman copy of a Greek bust of Miltiades the Younger, originally from the 5th−4th centuries BC, now at the Slovenian National Gallery]

Until the Ionian Revolt, Miltiades, known often as “The Younger”, ruled over the Chersonese. He was the nephew of Miltiades, known as Miltiades “The Elder”, son of Cypselus; Miltiades the Elder had gained control of the region in Thrace by being invited to intervene in a local war; A Thracian tribe, the Doloncians, were constantly loosing battles against their rival Apsinthian tribe. Fearing defeat, the Doloncians sent their kings to the Pythia at Delphi to ask for aid. They were told to invite the first man who extends to them hospitality into their lands, and make him their Founder. Receiving no aid as they headed south, they eventually reached Athens, and the home of Miltiades. A wealthy and noble man at the time, he saw these foreigners dressed in rags and carrying spears, and gave them the hospitality they sought. The Thracians told him of what the Oracle had told them, asking him if he would go along with the plan. Suffering under the rule of Pisistratus at the time and wishing to get out of it, and after asking the Oracle for advice, Miltiades accepted the offer.

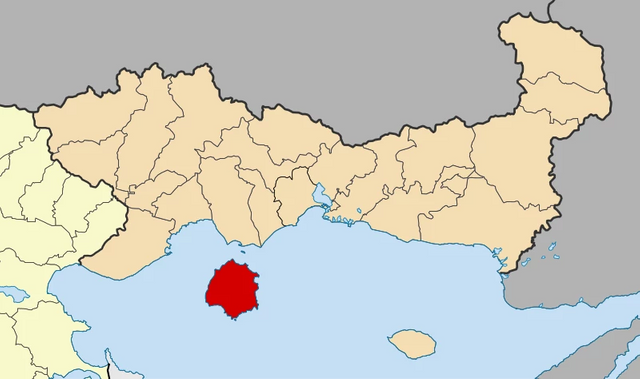

[ABOVE: Map of the Chersonese, modern-day European-Turkey]

Following a successful campaign into Thracian lands, Miltiades was made tyrant. As tyrant of the Chersonese, Miltiades ordered the construction of a wall to separate the Doloncians from the Apsinthians. Once this was achieved and the lands were made safer, he fixed his attention to Lampsacus, ordering it attacked. This attack, however, failed, and Miltiades was taken as a captive by the Lampsacenes. Croesus of Lydia, however, recognised Miltiades as a prominent man, and threatened Lampsacus to release him under the threat of being wiped out, to which they complied. Upon Miltiades gaining freedom, however, he was soon killed, dying without a clear heir. His kingdom and property was thus given to his half-brother, Stesagoras, and when he too was killed, the Chersonese was passed to his brother, Miltiades the Younger, nephew of the former Miltiades.

This Miltiades the Younger was sent over to the Chersonese by the Pisistratidae. Once there, he stayed in his home, supposedly as a means to honour the death of his brother; the local tribal chiefs joined him in mourning, whereupon they were all arrested. Peace was kept by Miltiades in the area by his 500 mercenaries, and his marriage to the daughter of the local Thracian king. When Persian ships arrived in his lands, he set sail to Athens.

MARDONIUS IN IONIA

[ABOVE: The Tomb of Darius I, depicting Gobryas, one of the Seven Conspirators and father of Mardonius]

It was soon after Miltiades’s goings-on in the Chersonese that a Persian general, Mardonius, (the son of Gobryas) headed for the coast of Asia Minor ahead of a large Persian army and navy. Reaching Cilicia, he headed the navy himself and left the army to march for the Hellespont, which they eventually reached, crossing altogether into Europe and heading straight for Athens and Eritrea. While these were the primary targets of the invasion, any settlements on their way there were also subject to the Persians, subduing the Thasians and enslaving Macedonians on their way south. At Athos, the Persian navy suffered a heavy blow due to storms, supposedly loosing them 300 warships, and 20,000 men were killed by either drowning, hypothermia, hitting rocks, or sharks. The land force too took some casualties on the way after a night attack by the Thracian Brygi tribe, killing several men and injuring Mardonius. They too, however, ended up defeated by the Persian army and enslaved. Suffering heavy casualties forced Mardonius to return to Asia with both the army and the fleet.

PERSIAN SUBJUGATION OF THASOS

[ABOVE: The Isle of Thasos, southern coast of northern Greece]

In the following year, king Darius ordered for the people of the isle of Thasos to demolish their own defensive walls and to dismiss their fleet; Thasos was using Persian gold to construct said longships and walls after claiming they had been besieged by Histiaeus. Thasos agreed to Darius’s demands, bringing their fleet to Abdera and knocking down their new walls. Darius next wished to see if the rest of the Greeks between Asia and Greece would submit or resist. Sending heralds throughout Greece to demand “earth and water”, Darius also ordered for Greek cities in Asia to begin constructing longships and transport vessels. Among the Greeks who gave the earth and water demand were the Aeginetans. This provoked Athens, who accused them of having Athens in mind as a target when agreeing to Darius’s demands. Making the most of this pretext, Athens sent delegations to Sparta, accusing the Aeginetans of betraying the Greeks. Persian messengers sent to Sparta and Athens to ask for their submission were killed; the Athenians threw the Persians off of a cliff, while the Spartans threw their Persian messengers down a well.

CLEOMENES OF SPARTA, AND THE ISLE OF AEGINA

[ABOVE: Location of the Isle of Aegina, south-west of Athens]

By this charge, king Cleomenes of Sparta sailed to Aegina to arrest the supposed ringleaders. There, he met resistance from locals who threatened to fight the Spartans, under the claim that Cleomenes was simply bribed by Athens and was thus not acting with permission from the Spartan authorities. However, it was actually a letter sent by Demaratus that made the Aeginetans make these accusations. Either way, Cleomenes left with his delegation, warning the ringleader, Crius, that a great deal of trouble was coming his way, telling him, “you had better have your horns coated with bronze”.

[ABOVE: Silver coins from Aegina, c.550–530 BC, depicting a Sea turtle and an incuse square punch with eight sections]

THE FATE OF CLEOMENES

While Cleomenes was dealing with the Aegnietans, Demaratus, the other Spartan king, was back in Sparta putting a bad name on his co-monarch. Cleomenes would later have the rival king deposed of by 491 BC, replacing him with his relative, Leotychidas, who Cleomenes took with him to Aegina to deal with the disputes. Two Spartan kings bearing down on Aegina was too much to handle, and resistance to Sparta ended. Ten of the wealthiest and most influential Aeginetans were taken away and given to their worst enemy: Athens.

Resistance to Cleomenes, however, had been brewing back at Sparta since Demaratus. Afraid of what his people may end up doing to him, Cleomenes fled to Arcadia, rallying their people against his own. Afraid of what Cleomenes may do to Sparta, the people welcomed back Cleomenes, restoring him to his full title as king. However, not long after his reposition to the throne did Cleomenes fall ill; he became deranged, and would reportedly poke his staff into stranger’s faces unprompted. He was thus placed in stocks, guarded only by a helot. Cleomenes threatened this “guard” to hand him a knife, and upon receiving it Cleomenes started tearing at his own flesh, starting with his shins, then his thighs, hips and then his stomach, at which point he dropped dead. The exact reasoning for such a suicide is still hotly debated; the geographer Pausanias and Herodotus himself both state that it could have resulted from Cleomenes’ destruction of a sacred tree in Eleusis, Attica, thus he did unto himself what he had done to a holy site. According to the Spartans of the time, however, Cleomenes’ spent a very long time living alongside Scythians, and their love for drinking unfiltered neat wine is what drove him insane.

THE HEIR OF CLEOMENES

Cleomenes was imprisoned in 490 BC and died the following year. Upon his imprisonment, he would be succeeded by his half-brother:

King Leonidas.

PERSIAN EXPEDITION TOWARDS ERETRIA

[ABOVE: Bust of an Achaemenid nobleman, believed to be Artaphrenes, from c.520-480 BC]

While Athens and Aegina continued to feud with one another, Darius made plans to conquer not only Athens, but all of Greece. In 490 BC, Darius appointed new military commanders in the places of Mardonius: a Mede named Datis, and Artaphrenes, son of Artaphrenes and Darius’ nephew. Their goal for now was to enslave Athens and Eritrea, and bring the captives to him personally. Datis was also accompanied by the former and last tyrant of Athens, Hippias, intent on reinstating him into power under Persia. Leading a large army, the two commanders headed for Greece, bolstering their army’s size with cavalry-transport and naval support on the way. The sea route taken towards Greece was an island-hopping one, starting at Samos. It’s likely they chose this route instead of a land-based invasion across the Hellespont due to their previous troubles in the Aegean around Athos, and the fact that they hadn’t yet subdued the isle of Naxos, which they now intended to take.

CAPTURE OF THE CYCLADES ISLANDS

[ABOVE: Satellite image of the Cyclades Islands. (Delos is South-West of Mykonos)]

[ABOVE: Location of the Isle of Naxos within the Cyclades]

The Naxians didn’t meet the Persians head-on when Datis and Artaphrenes landed there, making for the hills instead. Their quick pace for higher grounds left some behind, and the Persians took several prisoners, burning towns any sacred sanctuaries along the way. With this success, the Persians set off for more Greek islands.

DELOS AND KARYSTOS

[ABOVE: The city of Karystos, located in the south of the Isle of Euboea]

Meanwhile, the Delians of Delos also fled their island home, heading for Tenos. Datis, having some of his forces already stationed nearby, sent some of his fleet ahead of the Delians, to make for Rheneae. Datis sent heralds to the Delians, asking why they had fled, ensuring them that, even without orders from Darius, he would not be there to harm them. Datis then sailed away, not harming the Delians and made straight for Eretria. However, on the way, an earthquake struck Delos. This was taken as a sign of worse things to come for the islands’ inhabitants. Datis landed his ships at several Aegean islands along the way, capturing hundreds of people. The nation of Karystos on the Isle of Euboea put up resistance, but were eventually subdued after a siege.

THE SIEGE OF ERETRIA

[ABOVE: The Euboean city of Eretria]

(SIDE NOTE: The Greek city of Eretria should not be confused with the modern-day African nation of Eritrea. Similar names, but unrelated!)

Fearing of what was to come for them, Eretria asked Athens for support. Being sent four-thousand men, the Eritreans didn’t really have any strategy for these reinforcements. Some were willing to surrender cities to Persia, while others were ready to put up a fight in the hills. Aeschines, one of the notable Eretrian leaders, seeing this two-way divide, told the Athenian reinforcements to return to Athens, which they did. Datis soon after landed his ships outside the city, with several Eretrian manning the city walls. Fighting here was fierce. Six days into the fighting, however, two Eretrian nobles eventually surrendered the city over to Datis. As retribution for the burning of Sardis, they burnt the city’s sanctuaries to the ground, and under Darius’s orders, the population was enslaved. The Eretrian slaves taken by Datis to Darius would later be found and spoken to by Herodotus, who was key to most of the history known of this period.

Persia’s expedition was so far a huge success. They now set their eyes solely on Athens.

DATIS SENDS ENVOYS TO ATHENS

Datis was a Mede by descent. He had received the tradition from his ancestors that his Median homeland was established by people originally from Athens, and upon receiving this, he travelled to Athens with an army to demand the return of the sovereignty that belonged to his ancestors. (The myth goes that Medus, the founder of the kingdom of Media, was denied kingship in Athens and so fled east to found his own nation.) Datis’s demands were that if Athens returned the kingdom to him, he would let slide their burning of Sardis, but if they refused then they would meet a worse fate than Eretria. Speaking on behalf of the other ten Athenian general’s concession, Miltiades denied, stating it would be more appropriate for Athens to hold mastery over Media rather than Datis holding mastery over Athens. Datis made ready for battle.

MARATHON

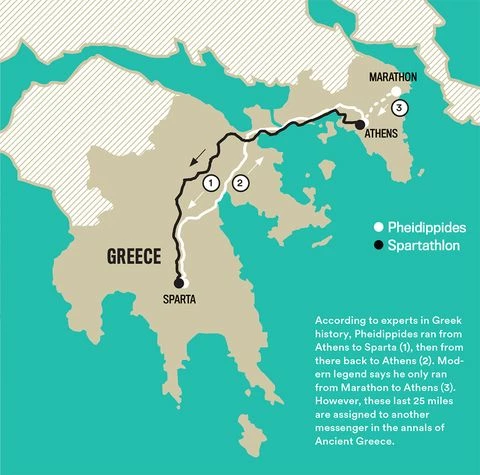

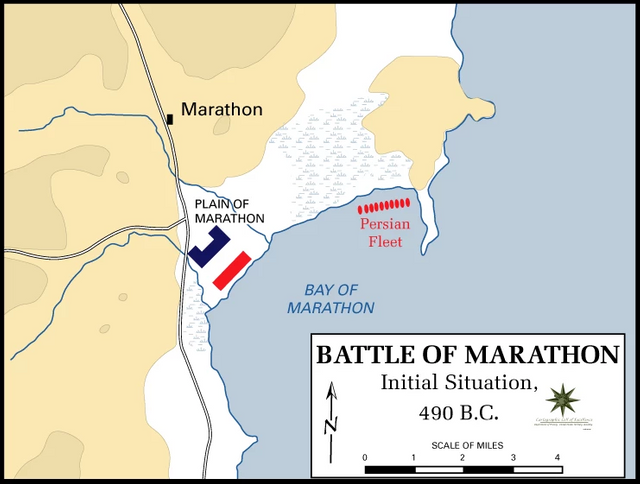

[ABOVE: The location of Marathon in relation to Athens and Sparta]

The location the Persians chose to land their forces was the bay of Marathon; it had good proximity to Eretria and had enough flat land to properly utilise their large cavalry forces. Hippias, the former Athenian tyrant, accompanied Datis and Artaphrenes on their expedition, and it was he who recommended the landing at Marathon. Hearing of the oncoming Persian army, Athens sent out ten-thousand men (that is, ten commanders commanding a thousand men each) to meet the Persians. One of these commanders was Miltiades, who took overall command of the entire Athenian army.

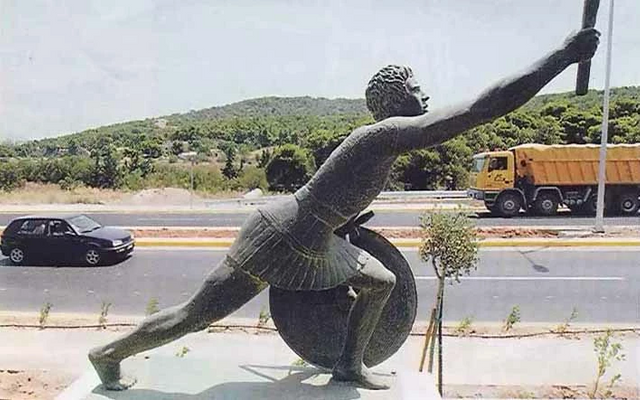

PHEIDIPPIDES

[ABOVE: A modern statue of Pheidippides along the Marathon road, Greece]

Before leaving the city, a runner/messenger named Philippides (perhaps more commonly known today as Pheidippides) to Sparta to ask for aid. On his way, he supposedly had an encounter with the God Pan by Mount Parthenium. Allegedly, Pan called for Pheidippides, asking why they had ignored Pan when they were always a friend of Athens. Believing in this experience, the Athenians would later go on to build a sanctuary to Pan on their Acropolis, worshipping him with torch-racing and sacrifices. Reaching Sparta, he asked them for aid, telling them that Eritrea, among other nations, had already fallen to Persia. Sparta agreed to join, but only once their festival, known as the Carneia, came to an end with the next full moon, and they were now allowed to partake in military campaigns in the meantime. Returning to Marathon, Pheidippides had impressively covered around 140 miles in just 36 hours of straight running.

[ABOVE: A statue of the God Pan, in the Capitoline Museum, Rome]

HIPPIAS'S HOMECOMING

One night before the landing at Marathon, Hippias had a dream in which he slept with his mother. He took this as a sign that he would regain his Athenian throne and die of old age. The next morning, the Eritrean prisoners were unloaded on the island of Aegilia, and the Persian army was unloaded at Marathon. As he jumped ashore, Hippias suffered with a coughing fit, in which he spat out one of his own teeth. He failed to find it after digging in the sand under the sea, and took this as a sign that the only part of Attica they would reclaim was the part where his tooth was. The rest would not be reclaimed.

CALLIMICHUS, THE PLATAEANS AND PREPARING FOR BATTLE

[ABOVE: A modern (2011) reenactment of Greek hoplites at the Bay of Marathon]

Meanwhile, the Athenian army had also lined up for battle opposite the Persians, accompanied now by a contingent of one-thousand men from Plataea, a subject state to Athens, bringing the total Greek force up to eleven-thousand. How to deal with the Persians was the subject of the Greek commanders now; Miltiades and others supported a direct attack, yet that may not have been the best strategy since the Greeks were heavily outnumbered. Alternatively, they could keep their defensive position and wait for the bigger Persian army to run out of supplies. Votes were cast by the eleven most senior commanders on what to do, until Callimichus, the elected War-Archon, was approached by Miltiades, and told that the future of Athens now lay in his hands, since Callimichus could cast the eleventh vote. He was eventually swayed over to Miltiades’ idea of a direct attack, who warned him of what the cowardice of several other Greeks who chose flight had resulted in for them. A stand-off of no fighting between the two armies took up four days.

[ABOVE: The initial positioning of both forces before the battle]

The Greeks took up battle positions. Callimichus manned the right wing, and the Plataeans manned the left wing. The battle line had to be stretched thin to match the Persian army’s line in length, so as to not be outflanked by them. The Greeks were supposedly outnumbered three-to-one. The outer wings, therefore, were made twice as thick as the rest of the army to better counter any outflanking manoeuvres. Standard Greek hoplite warfare dictated that the normal battle order was a slow, steady march, since each soldier was so heavily equipped, with shields interlocked. At Marathon, however, the Greek army charged at full-speed towards the Persians, the first time a Greek army had used this as a battle tactic, hoping to take them by surprise and suffer less damage at the hands of the several thousand archers the Persians had brought with them. The distance covered by the run was eight stades, roughly half a mile. Suffering only minor losses on the way due to arrow fire, the Greeks rammed into the Persian line, fighting remarkably well.

[ABOVE: Greek troops rushing forward at the Battle of Marathon, by Georges Rochegrosse, 1859]

THE BATTLE

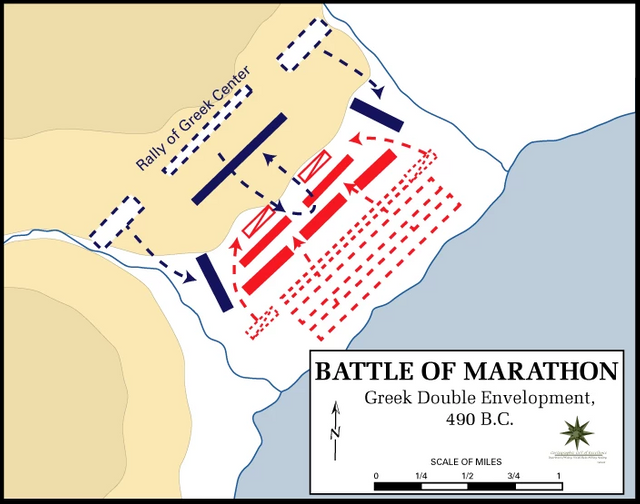

[ABOVE: The Greek line enveloping the larger Persian force]

The fighting went on for several hours. The thinner, weaker Greek centre collapsed under the weight of the Persian army, however Callimichus’ right wing and the Plataeans’ left wing, being double the depth of the rest of the Greek line, soon made ground, and began to slowly envelop the Persian army, until they were completely surrounded on three sides. Their only way now was backwards, towards their own ships for a quick get-away. The Greeks pursued the Persians back, and in this pursuit, Callimichus was impaled by spears and died in battle. Allegedly, so many spears impaled him that his body stayed upright even in death. Another casualty included Stesilaus, son of Thrasylaus, and another prominent Athenian named Cynegeirus, son of Euphorion, lost his hand to an axe while reaching for a Persian ship.

[ABOVE: Reconstitution of the Nike of Callimichus, erected in honour of the Battle of Marathon, later destroyed during the Persian sack of Athens, 480 BC, and now held in the Acropolis Museum, Athens]

[ABOVE: A 19th century illustration of Cynegeirus grabbing a Persian ship at the Battle of Marathon]

26 MILES

Seven Persian ships would be captured by the Greeks, with the rest sailing to Eritrea, to pick up the prisoners left there, and then sailing for Cape Sounio, south of Attica, intent on sailing round the landmass and reaching the undefended city of Athens. Miltiades now had to take his exhausted army, who had collapsed to their knees in their heavy armour under the beaming August sun, and force-march it back to Athens before the Persians could get there. This twenty-six mile march from Marathon to Athens would be a success, and the Persians would fail to land their army, forcing a retreat back to the empire.

This twenty-six mile march would also be forever immortalised as people from cities all around the world would later go on to celebrate the twenty-six mile-long Marathon run.

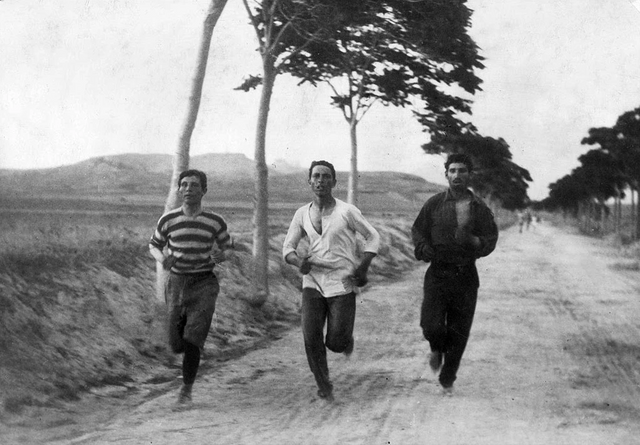

To clear something up, the story of Pheidippides the runner running to Athens, shouting "nenikēkamen!" ("We've won!") and then collapsing dead from exhaustion is unfortunately not true; It was invented in the first century AD by Plutarch. It doesn't mean that Pheidippides himself did not exist - it's still one-hundred percent plausible that he was the runner who was sent to Sparta to ask for aid before the battle - but the reason we celebrate the Marathon today really comes from the final 26 mile march of Miltiades and his exhausted men back to Athens. The first Olympic Games to stage the Marathon Run based around the false last run of Pheidippides was in 1896.

[ABOVE: "1896: Three athletes in training for the marathon at the Olympic Games in Athens", photographed and titled by Burton Holmes]

AFTERMATH

While the Persians suffered supposedly 6,400 losses, the Greeks only suffered 192. Marathon was a minor setback for the Persians, who had been very successful in their campaign up until Marathon, but it was a huge victory for the Greeks, who had taken off the veil of Persian invincibility and killed several thousands in the process.

DATIS

On the Persian's way back to Asia, Datis stopped off at Myconos, where he had another dream. What he dreamt of is unknown, but he woke up intent on searching his fleet. He found a gilded image of Apollo in a Phoenician vessel. It had been stolen from Delos by Persian-led soldiers, and Datis ordered it taken back to Delos. The Delians by then had returned back to Delos, and they were instructed to take the statue back to its original homeland at Delium, a territory owned by the Thebans. The statue would not be returned however, and twenty years later, Theban forces would reclaim the image and returned it to Delium after prompting by an oracle. Landing in Asia, Datis and Artaphrenes took the Eritrean prisoners to Darius in Susa, satisfied that the peoples who had first aided the Ionian revolt had now been enslaved. Thus, Darius did them no further harm and settled them in their own settlement to live in peace.

THE SPARTANS

As for the Spartans, they eagerly arrived to fight the Persians, and marched to Athens in just two days. While too late to reach the battle in time, they were keen to see what a Persian soldier looked like, and so marched to Marathon to inspect the dead. They expressed their praises to Athens for fending off such a large force so swiftly, yet I imagine this was said with an underlying level of loathing since their age-old rival had been the one to claim such a huge victory and not them. The Spartan forces soon returned home.

MEMORIAL

[ABOVE: The mound (soros) where the Athenians buried their dead after Marathon]

The 192 fallen Greek soldiers were honoured with a burial: an originally 12 metre-high mound that can still be seen today. Traces of this Greek hero cult have been found; one modern theory states that this 192 is also found on the Parthenon, which has 192 mounted figures on its frieze, carved by Pheidas a couple of decades later. The Plataeans too got to bury their own soldiers in a separate mound.

[ABOVE: The mound where the Plataeans buried their dead after Marathon]

MILTIADES' ATTEMPT ON PAROS

[ABOVE: Miltiades' helmet, given as an offering to the temple of Zeus, Olympia, by Miltiades, with the inscription: "ΜΙΛΤΙΑΔΕΣ ΑΝΕ[Θ]ΕΚΕΝ [Τ]ΟΙ ΔΙ" ("Miltiades dedicates this helmet to Zeus"), now held in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia]

Following the Battle of Marathon, Miltiades now had a high reputation to his name, so much so in fact that when he asked the government for seventy warships and an entire army without telling them why exactly, they simply let him have what he wanted. His goal was to capture the isle of Paros. His given reasoning was that Paros sent a trireme in support to the Persians during their invasion of Greece, yet this was merely an excuse; Lysagoras of Paros turned Hydarnes against him during a personal feud, so the reasoning was in fact more personal. Either way, arriving at Paros, Miltiades besieged the city, sending in a herald to ask for 100 talents under the threat that he would otherwise keep the city besieged until it fell. Yet the Parians remained stubborn, rebuilding some of the weaker sections of the wall wherever they could during the siege in the nights to double the walls original height.

FAILED EXPEDITION

[ABOVE: Location of the Isle of Paros, part of the Cyclades Islands]

What follows next varies in sources; Parian sources state that a female Parian captive of Miltiades, a priestess called Timo, asked to meet privately with Miltiades. She advised him on how to take the city, and Miltiades obeyed, making his way over to a hill in front of the city and scaling a small wall surrounding a sanctuary to Demeter. The intention here may have been to interfere with sacred objects held within, but when he reached the sanctuary’s entrance, he was suddenly overcome with fear, and left. Retracing his steps, he made it back to the wall, but caught his leg on the way down, and wrenched his thigh. Miltiades sailed back to Athens, having only besieged the city for twenty-six days and having brought back nothing from his expedition. Parians, meanwhile, were intent on killing Timo for attempting to aid Miltiades, but the Delphic Oracle they sought advice from told them otherwise, claiming she was not guilty and that Miltiades was fated to die a horrible death anyway.

DEATH OF MILTIADES

Upon returning to Athens, Miltiades was scorned by the city. Scorniing him the most was Xanthippus, who put him on trial and sentenced him to death for deceiving the Athenians. His injured thigh, however, stopped him from appearing in front of the people himself to make his defence, so his friends had to do it for him while he lay down. His friends defended him by referring to Miltiades’ successes against Lemnos, which he had captured and brought under the Athenian fold, and of course his great success at Marathon. This argument worked; the death penalty was lifted for Miltiades, yet he was still forced to pay fifty talents. Before he could pay up, though, he died from his thigh injuries. His son, Cimon, would pay the fifty talents and offer himself up for imprisonment instead, in the hopes that he would get to have his father’s body for himself to bury.

OSTRACISM

Marathon gave a huge boost of confidence to Athens’s new system of democracy, but equally gave them distrust to its old aristocracy; soon after, the system of Ostracism (from the Greek “ostrakon” meaning “potsherd”, as that was what Ostracism votes were counted on) was introduced and used for the first time in 487 BC, (although ostracism was likely first introduced by Kleisthenes in his reforms) allowing the Athenian people to vote without debate for someone they wised to remove from the city. Later that year, the individual would spend ten years out of Athens, but still retained their citizen and property rights.

[ABOVE: Ostraka shards from 482 BC]

Perhaps the most famous Athenian to be ostracised would also receive the most votes to be so: 1,490 votes for the man who would save Greece in the next Persian invasion to come: Themistocles.

ROBERT GRAVES' POEM

[ABOVE: Robert Graves, photographed in 1929]

Robert Graves (b.1895, d.1985) was a First World War soldier and poet who wrote about Marathon. He was likely correct in thinking Persia saw Marathon as a minor setback in their campaign overall. While light-hearted, his poem is well renowned as a major piece of work. The poem speaks through the words of a Persian, and his words show that political “spinning” was still a thing even back then, yet Graves’ own pompousness still shines through:

"Truth-loving Persians do not dwell upon

The trivial skirmish fought near Marathon.

As for the Greek theatrical tradition

Which represents that summer’s expedition

Not as a mere reconnaissance in force

By three brigades of foot and one of horse

(Their left flank covered by some obsolete

Light craft detached from the main Persian fleet)

But as a grandiose, ill-starred attempt

To conquer Greece - they treat it with contempt;

And only incidentally refute

Major Greek claims; by stressing what repute

The Persian monarch and the Persian nation

Won by this salutary demonstration:

Despite a strong defence and adverse weather

All arms combined magnificent together."

- Robert Graves, “The Persian Version”

NEXT BLOG: "THE RISE OF XERXES, 486-480 BC: START OF THE SECOND INVASION"

https://www.publish0x.com/ancient-greek-and-roman-history/the-rise-of-xerxes-486-480-bc-start-of-the-second-invasion-xppjekr

SOURCES

• Herodotus's "Histories"

• Diodorus Siculus, "Library of History"

• Philip Parker, "World History"

• Nic Fields, "Thermopylae 480 BC, Last Stand of the 300"

• Oswyn Murray, "Early Greece"

• Robin Osborne, "Greece in the Making 1200 - 479 BC"

YOUTUBE LINKS

(I do NOT own these videos)

"Decisive Battles - Marathon (Greece vs Persia", uploaded to YouTube by "Zakerias Rowland-Jones"

"Battle of Marathon | Animated History" by "The Armchair Historian"

"The Battle of Marathon (3D Animated Documentary) 490 BCE" by "Hoc Est Bellum"

"Battle of Marathon - Persia and Greece Collide!" by "Youre History"

"Miscellaneous Myths: Medea" by "Overly Sarcastic Productions"

MY HISTORY COMMUNITY:

https://steemit.com/created/hive-133974

MY TWITTER:

https://twitter.com/HarveyPeirson

All feedback - positive and/or critical - is appreciated!

All images used are copyright-free

Don't forget to rate this post if you enjoyed it

Thanks for reading :)