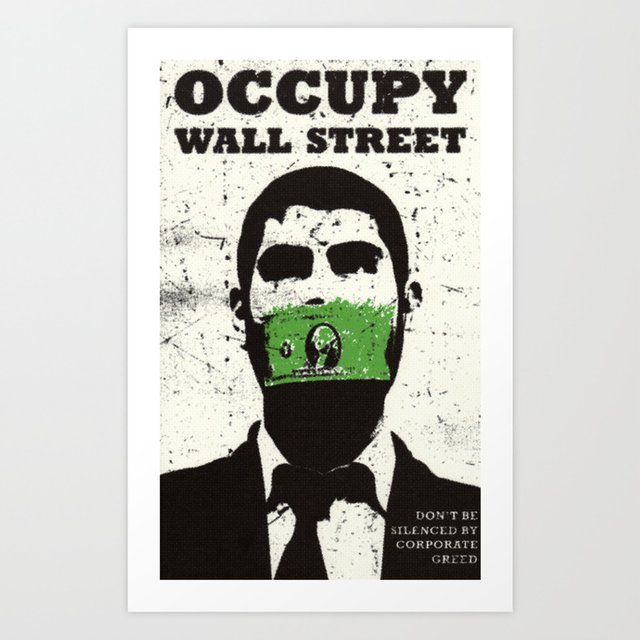

Occupy Wall Street and the Media, 12 Years on and, How it Still Matters (An Essay)

Disclaimer: This text is around 3000 words, not a quick text.

Unquestionably, the world is currently experiencing an acutely testing period. One of its most challenging times in modern history, financial and economic pressure is palpable (IMF, 2020). The COVID19 pandemic has had an enormous impact on almost every part of society. The financial sector, for instance, was severely affected by the pandemic. Governments, as well as the private sector, are yet to learn the final real damage caused by the virus (Kettle, 2020). Although some are convinced that such a crisis has been unseen in generations.

It is equivalently important to highlight the impact of the previous financial crisis which took place in 2008. The global financial crisis had a tremendous impact on society, exposing the dependency on the sector (Global Issues, 2013). The crisis also intensified the level of inequality among communities (Stockhammer, 2011). and, as a result, creating the Occupy Wall Street movement (OWS).

This project aims to succinctly explore what triggered the society to express its unsatisfaction with the system in place in the form of the Occupy movement. This essay will focus on the complexed relationship between Social Movements (SM) and the Occupy Wall Street Movement (OWS). In parallel, using SM theories to the movement’s structure and strategy. Furthermore, this essay will explore the OWS using the Quadruple A theory. Breaking down into ‘A’s to analyse many areas within the movement. Besides that, this project will apply different SM theories to interpret the stages of the movement and, its relationship with the media, from its beginning to its growth and its critique.

"Primarily, I think [Occupy] should be regarded as a response, the first major public response, in fact, to about thirty years of a really quite bitter class war that has led to social, economic and political arrangements in which the system of democracy has been shredded" (Chomsky, 2012, p54).

To understand the origin of the OWS, close attention must be paid to the core provocation of the provocateur. Simply presented, what triggered the 2008 financial crisis? In brief, the 2008 global financial crisis was primarily caused by the lack of control and regulation in the financial sector. Such a scenario allowed banks to take part in the buy and sale of contracts with hedge funds. Banks demanded re-mortgages to guarantee the profitable sale of these contracts. As a result, 'interest-only' loans were created, which became accessible to people with low credit (Bubevski, 2019, p192).

Subsequently, house purchasing and re-mortgages escalated as a form of investments. Hence, creating a housing bubble, resulting in borrowers facing themselves unable to cope with payments.

Banks and other financial institutions were involved in those transactions mostly. Once payments were not made, those institutions began to also struggle. Leading some to bankruptcy and others to seek support by governments. The aftermath of the crisis caused an unprecedented unemployment level in the US (Friedman, 2011, 279-281). It is important to highlight that the crisis was more complicated than explained in this piece. Yet, considering the crisis itself is not the goal of this essay, only a short view was dedicated to exploring the path to the OWS.

The housing bubble burst and the crisis expanded further, reaching the public. A group of people began to express their frustration due to the lack of accountability among economic institutions. Anger shifted to elites who were being blamed for the situation. One could argue that it was the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression (Brock, Glasbeek and Murdocca, 2014, p378) A group of activists, students and organisers gathered near Wall Street to discuss changing the world. Among the group were mostly Americans, unhappy with the budget cut, but also others involved in protests across Europe and the Arab peninsula. The group began to discuss issues around economic hardship in America. Some of the participants who attended protests in Spain suggested adopting the strategy. Although the idea of a general assembly in America seemed unusual at the beginning, it was well-received (Van Gelder, 2011, p16-18).

This leaderless structure movement aimed to gather participants and discuss social issues. A movement based on horizontalism structure in which by consensus an outcome would be reached. The goal was based on the ideal society, ‘non-hierarchical, prefigurative alternatives that allegedly embody the desired ideal society’ (Angelovici, Dufour and Nez, 2016, p28). In brief, the movement had gained great support and its proportion had grown rather fast. Between September and October of 2011, marches continued in the streets of New York. At some point, reaching around 15,000 protesters (Gabbatt, 2011). As a result, around 700 arrests were made, despite no claims of violence from protesters. (BBC, 2011).

The first stage in which OWS’ relationship with mass media can be analysed around the communicative structure in which the media represented the movement within the media, focusing primarily on how activists attract the attention of its viewers. The unseen structure of OWS and its consensus strategy brought plenty of interest. This stage also focused on numbers, damage caused and how much noise is produced related to the movement. The second stage focused on the structure of the discourse that was formed, aimed at encouraging a counter-narrative and propagating it independently of the main media. The third stage focused on the opportunities and resistance offered by technology. (Cammaerts, 2012, p122). As part of any SM, mass media plays an extremely important role. Spreading awareness, capture public support, form and influence the discourse around the core beliefs of an SM is heavily facilitated by the structure provided by mass media (Koopmans, 2004). This motion leads one to believe that mass media and SMs not only support each other but depend on one another. In one hand, SM ‘is highly dependent on media coverage turn bystanders into potential participants and to convey their message to the protest targets’ (Vliegenthart and Walgrave, 2012, p394-395). In another, mass media and the OWS experienced a complicated relationship; both groups share similar characteristics such as the struggle for continuous popularity, the goal to maximise its message and both are constantly being challenged by different people or organisation (Rucht, 2004, p29).

The mass media is a vital instrument used by OWS to expand its popularity and gain attention which results in its expansion nationally, then globally. Without such a vehicle, it is fair to conclude that OWS would not have obtained such growth. However, one must not ignore that media, including social media, are organisations oriented towards profit to remain up and running. Consequently, messages distributed by SM in those platforms can lose its impact as often they found themselves fighting for coverage among sponsorship advertisement and the sales of products (Rohlinger, 2015). Precisely because media outlets are companies dependent on profit, its ability to remain interesting is crucial. Thus, its sales must remain at a certain level of constant profitability, which indicates how each media locates its sale strategy. Sale strategy can be interpreted as how a story would be portrayed.

This strategy leads to outlets to publish questionable versions of an event to increase sales. It is fair to conclude that media nowadays ‘have brand reputations for their mix of hard and soft news’ (Hamilton, 2003, p25). Such a phenomenon can be interpreted as the ‘protest paradigm’. Which is often used to portray news media to diminish the legitimacy in a specific subject such as OWS (Weaver and Scacco, 2012, p64). Media shifts its attention from the movement's ideology to disruptions related to the movement (Shahin, Zheng, Sturm and Fadnis, 2016, p145). As a result, exposing a clear limitation with such a strategy related to the relationship between both parts. Although SMs and the mass media share similarities, the core beliefs are far apart from each other. Resulting in an unequal and rather limited partnership.

‘Occupy Wall Street' Protests Turn Violent When Demonstrators Clash With Police’ (Fox News, 2011).

‘Woman raped in tent at anti-capitalist demonstration’ (Mirror, 2011).

‘Protesters Look for Ways to Feed the Web’ (NYT, 2011).

‘Mass arrests at Occupy Wall Street protests’ (BBC, 2011).

Different outlets portray SM differently to reach their audience. As a result, messages become confusing and misleading in some cases. Such an approach can lead movements to lose its coverage (Foellmer, Lèunenborg and Raetzsch, 2018). In opposition to the lack of media exposure, SMs adopt a different strategy. Rucht (2004) defines this approach as the quadruple ‘A’:

Abstention refers to the neglection of mass media, communication is often shifted internally.

Attack refers to a direct critique of media.

Adaptation refers to the stage in which the movement adapts its approach to maximise media coverage.

Alternatives refer to the implementation of its forms of communication (Kaun, 2016).

Following Rucht’s theory, OWS can be analysed using in those terms. OWS seeks ‘alternatives’ by creating its website which in it, exercise ‘attacks’ by criticising governments. Moreover, ‘adaptation’ is exercised by the language and approach used in its forum. Lastly, ‘abstention’ is expressed as its main channel of communication moves internally. Hence, abstaining itself from the mass media (Occupywallstreet.org, 2020). Another factor which makes this relationship particularly fragile lies in entertainment. Although the mass media works as a facilitator to SMs, at the same time, SMs must produce strong, interesting contents. Most importantly, SMs cannot control what type of information is associated with them (Doerr, Mattoni and Teune, 2013).

The relationship between SM and the mainstream media can be described as an asymmetrical relationship. Although SMs are highly dependent on the media, the media outlets are not necessarily as dependent on SM to build their content (Maria, 2014, p14). This scenario leads to misinterpretation, misleading coverage and distorted coverage from the media. This nonreciprocal relationship between both parts could have influenced the OWS to enter one of the ‘A’ stages of Ructh’s theory, ‘abstention’. Furthermore, ‘attack’ can be expressed in other ways by SM, the critique can be exercised in a variety of forms, especially as technology becomes embedded in the current society. Traditionally, protests targeting mainstream media were expressed in forms of marches, joined by a certain number of protesters bringing awareness of media misrepresentation (Occupy London, 2013). OWS in another hand had exercised its ‘attack’ strategy slightly different:

Newspapers and television networks have been rebuked by media critics for treating the movement as if it was a political campaign or a sideshow — by many liberals for treating the protesters dismissively, and by conservatives, conversely, for taking the protesters too seriously.

The protesters themselves have also criticized the media — first for ostensibly ignoring the movement and then for marginalizing it (Stelter, 2011). In this scenario, OWS is making use directly or indirectly of a media outlet to express its criticism against other media outlets. Following Rucht’s quadruple A approach, ‘alternatives’ and ‘adaptation’ can be analysed in the same scenario. OWS’s approach to alternatives and adaption is exercised in its webpage. OWS adapt itself by remaining constantly updated with current issues such as COVIT19 pandemic and local issues across the US. Its format covers events outside the subject such as Wall Street and inequality. Lastly, ‘alternatives’ is exercised in its webpage where the group is no longer solely dependent on the mass media. It produces its content and raises funds through its website (OccupyWallSt, 2020).

It is imperative to state that although Ructh’s theory breaks down an alternative for how SMs can be analysed, in particular OWS, such relationship is ever more complex. OWS’s attack, alternatives, abstention and adaptation are not exercised outside the mainstream media. Rather the opposite, its strategy for using the quadruple A are instruments to gain access to the mainstream. The use of the internet, for instance, is perhaps the most powerful modern tool in which OWS relies upon to gain exposure. The internet, while certainly, no panacea for the continuing inequalities of strategic and symbolic power mobilized in and through the mass media, evidently contains a socially activated potential to unsettle and on occasion, even disrupt the vertical flows of institutionally controlled ‘top-down’ communications and does so by inserting a horizontal communicative network into the wider communications environment (Cottle, 2008, p859).

Moreover, close attention should be paid to ‘alternative’, especially how the internet played a vital role in OWS’s strategy. ‘Occupy’s social movements existed in both the public space and the network society but it was Occupy’s prominence on the internet, on social networking sites, that led to its success. Social networking sites can assemble all different people, with varying backgrounds together and this is exactly what Occupy did. OWS’ tweet account still has almost 200k followers, and its almost 35k tweets (@OccupyWallSt, 2020) indicates the intention of the movement to stay active.

However, despite OWS’s message ‘We are the 99%’ (Occupywallst.org, n.d.) and common knowledge that the movement focused on redistribution of wealth and reconstruction of the system that is in operation. One cannot ignore fundamental criticism made nonmedia outlets but expressed by media outlets. One of the main criticism is based on the terminology used by the movement, ‘Occupy Wall Street’ is a term used to define the goal of the movement which is to “occupy” a space or an area which was already occupied and taken away from the indigenous groups who lived there before. Moreover, most of wall street area was built by African slaves (Campbell, 2011) and both groups, native American and African Americans are misrepresented in the movement.

Despite the national figure stating that African Americans experience twice as much unemployment than the white community (U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics, 2020), only 1.6% of African Americans are represented in the movement, which raised serious concerns on the movement’s ability to deal with its lack of diversity (Captain, 2011). Other criticisms were expressed by the African American community highlighting that the movement only began to gain popularity when the white community started to experience what African Americans have been dealing with for decades (Ross. and Rivers, 2018, p180). Such a statement can be interpreted as an important challenge to the movement’s core beliefs.

This project has concluded that a thorough understanding of how the relationship between SMs and the mass media cannot be taken for granted. It is crucially useful to appreciate the stages in which SMs are likely to go through. With this in mind, one can more broadly make sense of the scenario, thus make an educated prediction of stages to come.

The good:

The partnership between OWS and the mass media which provides:

Engagement with its target audience.

Capture attention and gain acknowledgement by the public.

Inspire and advocate for discourse among the subjects.

Gain support from the public and media outlets.

The bad:

Protest paradigm

News outlet not necessarily interested in the ideology but a profitable story to sell

Asymmetrical relationship, a nonreciprocal relationship will produce nonreciprocal results

And, the ugly:

SMs do fail and the great majority struggles to remain popular.

The amount of time and financial resources invested in an SM play a crucial role in its performance and financial inequality is the very core of OWS’s ideology.

SMs are not all the same and its structure revolves as fast as technology is, thus, new ways of interaction are constantly changing.

SMs are likely to be scrutinised much more vigorously than any organisation or private company. Since most SMs advocate for causes which involves minority groups and somehow challenges the status quo, public opinion lies on the perception that SMs and protests must exist in a perfect structure. Where it exists outside the social reality, where inequality, race and gender issues do not coexist within it. Hence, this lack of realistic expectation and double standardisation is extremely prejudicial for the growth of any SM.

One must acknowledge the fine line between love and hate allying OWS and the mass media, a protest paradigm should be forecasted not by OWS by any SM which experience popularity. One could argue that the protest paradigm phenomenon is a result of an asymmetrical relationship between a social movement and the mass media. It is crucial to acknowledge that, although the quadruple A is a useful strategy to minimise an SM’s forgetfulness, once an SM’s momentum has passed, an incredible amount of work needs to be devoted to keeping the movement contemporarily popular. OWS has shown extreme strength recycling itself and bringing awareness beyond the Wall Street crisis. Moreover, it is important to highlight that technology is not a binary phenomenon located on either end of the spectrum, but a tool used by both parts to gain attention, it brings visibility; the internet, for instance, felicitates a broader and more opened discussion among society (Višňovsky and Radošinská, 2018, p75-76). The complexity of this relationship between OWS and the mass media could be inserted in the fragile area which lives in the grey area between the mass media as a popularity facilitator and the mass media as a profit-making machine.

SMs have different strategies to establish communication between media outlets and vice versa. Media outlets can choose to ignore, engage directly with protesters or misrepresent them. Whether the media chooses to understand the message behind an SM or seek personal information from a protester to influence public opinion is unforeseen and uncontrollable by the movement (Rucht, 2004, p25). One could argue that the OWS has reached positive results in parts because it understood those areas. Furthermore, although the argument that the mass media must be profitable is valid, profitability does not necessarily signify that it needs to adopt an unethical manner to generate income.

By the time of this essay’s completion, COVIT19’s cure or vaccine has not yet been found, a global financial crisis is perhaps inevitable (Ercolano, 2020). One must not ignore the lessons learnt from the last financial crisis, therefore, adopting a similar strategy to tackle the future crisis, expecting a different outcome would be considered insane.

Reference:

Angelovici, M., Dufour, P. and Nez, H., 2016. Street Politics In The Age Of Austerity. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

BBC News. 2011. Hundreds Arrested In US Protest. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-15140671 [Accessed 10 May 2020].

BBC News. 2011. Mass Arrests At Occupy Protests. [online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-15784439 [Accessed 11 April 2020].

Bubevski, V., 2019. Six Sigma Improvements For Basel III And Solvency II In Financial Risk Management. Hershey: IGI Global.

Brock, D., Glasbeek, A. and Murdocca, C., 2014. Criminalization, Representation, Regulation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Cammaerts, B., 2012. Protest logics and the mediation opportunity structure. European Journal of Communication, [online] 27(2), pp.117-134. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0267323112441007 [Accessed 12 May 2020].

Captain, S., 2011. Infographic: Who Is Occupy Wall Street?. [online] Web.archive.org. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20120719184547/http://www.fastcompany.com/1792056/occupy-wall-street-demographics-infographic [Accessed 15 May 2020].

Campbell, E., 2011. A Critique of the Occupy Movement from a Black Occupier. The Black Scholar, [online] 41(4), pp.42-51. Available at: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=ITOF&u=uvw_ttda&id=GALE%7CA293544180&v=2.1&it=r [Accessed 13 April 2020].

Chomsky, N., 2012. Occupy. New York: Penguin Books.

Cottle, S. (2008). Reporting demonstrations: the changing media politics of dissent. Media, Culture & Society, 30 (6), 853–872.

Doerr, N., Mattoni, A. and Teune, S., 2013. Advances In The Visual Analysis Of Social Movements. 1st ed. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Ercolano, P., 2020. Recession Appears 'Inevitable' Amid COVID-19 Crisis. [online] The Hub. Available at: https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/03/16/coronavirus-recession-q-and-a/ [Accessed 16 May 2020].

Fox News. 2011. 'Occupy Wall Street' Protests Turn Violent When Demonstrators Clash With Police. [online] Available at: https://www.foxnews.com/us/occupy-wall-street-protests-turn-violent-when-demonstrators-clash-with-police [Accessed 11 February 2020].

Foellmer, S., Lèunenborg, M. and Raetzsch, C., 2018. Media Practices, Social Movements, And Performativity. New York: Routledge.

Gabbatt, A., 2011. Occupy Wall Street: protests and reaction. The Guardian, [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/blog/2011/oct/06/occupy-wall-street-protests-live [Accessed 10 May 2020].

Global Issues, 2013. Global Financial Crisis. [online] Global Issues. Available at: https://www.globalissues.org/article/768/global-financial-crisis [Accessed 1 May 2020].

Hamilton, J., 2003. All The News That's Fit To Sell. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

IMF, 2020. The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since The Great Depression. [online] IMF. Available at: https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/ [Accessed 9 April 2020].

Kaun, A., 2016. ‘Our time to act has come’: desynchronization, social media time and protest movements. Media, Culture & Society, [online] 39(4), pp.469-486. Available at: https://journals-sagepub-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1177/0163443716646178#_i13 [Accessed 11 May 2020].

Klusener, E., 2018. The internet: Can it really influence social movements?. [Blog] University of Manchester: Protest and repression, Social Media, Available at: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/global-social-challenges/2018/06/17/the-internet-can-it-really-influence-social-movements/ [Accessed 13 May 2020].

Maia, R., 2014. Recognition And The Media. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Occupylondon.org.uk. 2013. MARCH AGAINST MAINSTREAM MEDIA REPORT. [online] Available at: https://occupylondon.org.uk/march-against-mainstream-media/ [Accessed 12 May 2020].

Occupywallst.org. 2020. Forum Post: Police State Beatings & Murder | Occupywallst.Org. [online] Available at: http://occupywallst.org/forum/everyone-needs-to-see-this-anonymous-code-blue-201/ [Accessed 12 May 2020].

Kettle, M., 2020. We simply don't know what kind of Britain will awake from all this. The Guardian, [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/26/britain-covid-19-predictions [Accessed 9 April 2020].

Koopmans, R., 2004. Movements and media: Selection processes and evolutionary dynamics in the public sphere. Theory and Society, [online] 33(3/4), pp.367-391. Available at: https://link-springer-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/content/pdf/10.1023/B%3ARYSO.0000038603.34963.de.pdf [Accessed 11 April 2020].

Mirror. 2011. Woman Raped In Tent At Anti-Capitalist Demonstration. [online] Available at: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/woman-raped-in-tent-at-anti-capitalist-demonstration-275887 [Accessed 11 January 2020].

Nytimes.com. 2011. Protesters Look For Ways To Feed The Web. [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/25/business/media/occupy-movement-focuses-on-staying-current-on-social-networks.html [Accessed 19 January 2020].

Occupywallst.org. 2020. Occupy Wall Street | NYC Protest For World Revolution. [online] Available at: http://occupywallst.org/ [Accessed 11 May 2020].

Rohlinger, D., 2015. Abortion Politics, Mass Media, And Social Movements In America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ross., A. and Rivers, D., 2018. Sociolinguistics Of Hip-Hop As Critical Conscience. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rucht, D. 2011. The quadruple a. In: Van de Donk, W., Loader, B., Nixon, P. and Rucht, D., 2004. Cyberprotest. London: Routledge.

Shahin, S., Zheng, P., Sturm, H. and Fadnis, D., 2016. Protesting the Paradigm. The International Journal of Press/Politics, [online] 21(2), pp.143-164. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1940161216631114 [Accessed 13 May 2020].

Stelter, B., 2011. Protest Puts Coverage in Spotlight. The New York Times, [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/21/business/media/occupy-wall-street-puts-the-coverage-in-the-spotlight.html [Accessed 12 May 2020].

Stockhammer, E. 2011, "Wage-led growth: An introduction*", International Journal of Labour Research, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 167-187.

Twitter.com. 2020. Occupy Wall Street (@Occupywallst) On Twitter. [online] Available at: https://twitter.com/OccupyWallSt [Accessed 13 May 2020].

U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics, 2020. Labor Force Statistics From The Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: Division of Labor Force Statistics.

Van de Donk, W., Loader, B., Nixon, P. and Rucht, D., 2004. Cyberprotest. London: Routledge.

Višňovsky, J. and Radošinská, J., 2018. Social Media And Journalism. London: IntechOpen.

Weaver, D. and Scacco, J., 2012. Revisiting the Protest Paradigm. The International Journal of Press/Politics, [online] 18(1), pp.61-84. Available at: https://journals-sagepub-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1177/1940161212462872 [Accessed 13 May 2020].