Somapura Mahavihara (Paharpur Buddhist Bihar)

History:

Somapura Mahavihara (Paharpur Buddhist Bihar) an important archaeological site in Bangladesh, situated in a village named Paharpur (Pahadpur) under the Badalgachhi Upazila of Naogaon district. The village is connected with the nearby Railway station Jamalganj, the district town Naogaon and Jaipurhat town by metalled roads. It is in the midst of alluvial flat plain of northern Bangladesh. In contrast to the monotonous level of the plain, stands the ruins of the lofty (about 24m high from the surrounding level) ancient temple which was covered with jungle, locally called Pahar or hill from which the palace got the name of Paharpur. The site was first noticed by Buchanon Hamilton in course of his survey in Eastern India between 1807 and 1812. Westmacott next visited it. Sir Alexander Cunningham visited the place in 1879. Cunningham intended to carry out an extensive excavation in the mound. But he was prevented by zamindar of Balihar, the owner of the land. So he had to be satisfied with limited excavation in a small part of the monastic area and top of the central mound. In the latter area he 'discovered the ruins of a square tower of 6.70m (22 ft) side with a projection in the middle of each side'. The site was declared to be protected by the Archaeological Survey of India in 1919 under the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904.

A number of monasteries grew up during the Pāla period in ancient Bengal and Magadha. According to Tibetan sources, five great Mahaviharas stood out: Vikramashila, the premier university of the era; Nalanda, past its prime but still illustrious; Somapura Mahavihara; Odantapurā; and Jaggadala. The monasteries formed a network; "all of them were under state supervision" and there existed "a system of co-ordination among them ... it seems from the evidence that the different seats of Buddhist learning that functioned in eastern India under the Pāla were regarded together as forming a network, an interlinked group of institutions," and it was common for great scholars to move easily from position to position among them.The excavation at Paharpur, and the finding of seals bearing the inscription Shri-Somapure-Shri-Dharmapaladeva-Mahavihariyarya-bhiksu-sangghasya, has identified the Somapura Mahavihara as built by the second Pala king Dharmapala (circa 781–821) of Pāla Dynasty. Tibetan sources, including Tibetan translations of Dharmakayavidhi and Madhyamaka Ratnapradipa, Taranatha's history and Pag-Sam-Jon-Zang, mention that Dharmapala's successor Devapala (circa 810–850) built it after his conquest of Varendra. The Paharpur pillar inscription bears the mention of 5th regnal year of Devapala's successor Mahendrapala (circa 850–854) along with the name of Bhiksu Ajayagarbha. Taranatha's Pag Sam Jon Zang records that the monastery was repaired during the reign of Mahipala (circa 995–1043 AD).

The Nalanda inscription of Vipulashrimitra records that the monastery was destroyed by fire, which also killed Vipulashrimitra's ancestor Karunashrimitra, during a conquest by the Vanga army in the 11th century. Over time Atish's spiritual preceptor, Ratnakara Shanti, served as a sthavira of the vihara, Mahapanditacharya Bodhibhadra served as a resident monk, and other scholars spent part of their lives at the monastery, including Kalamahapada, Viryendra and Karunashrimitra. Many Tibetan monks visited the Somapura between the 9th and 12th centuries. During the rule of the Sena dynasty, known as Karnatadeshatagata Brahmaksatriya, in the second half of the 12th century the vihara started to decline for the last time. One scholar writes, "The ruins of the temple and monasteries at Pāhāpur do not bear any evident marks of large-scale destruction. The downfall of the establishment, by desertion or destruction, must have been sometime in the midst of the widespread unrest and displacement of population consequent on the Muslim invasion."A copperplate dated to 159 Gupta Era (479 AD) discovered in 1927 in the northeast corner of the monastery, mentions donation of a Brahmin couple to Jain Acharya Guhanandi of Pancha-stupa Nikaya at Vata Gohli, identifiable as the neighbouring village of Goalapara.

Archaeological survey of india, varendra research society of Rajshahi and University of Calcutta jointly started regular and systematic excavation here in 1923. In the beginning the joint mission carried out the work with the financial help of Kumar saratkumar ray of Dighapatia Zamindar family and under the guidance of DR Bhandarkar, Professor of Ancient History and former Superintendent of Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle. The work was confined to a few rooms at the south-west corner of the monastery and the adjoining courtyard. RD Banerjee, who excavated in the northern part of the central mound, resumed the work in 1925-26. From the next season (1926-27) onward excavation was carried out under the supervision of KN Dikshit with the exception of seasons of the 1930-32. In these two seasons GC Chandra conducted the excavation. In the last two seasons (1932-34) the work was carried out at satyapir bhita, a mound at a distance of 364m east of the central temple. During Pakistan period Rafique Mughal excavated lower levels of a few monastic cells on the eastern wing, but the results were never published. After independence (1971) the department of archaeology of Bangladesh brought the site under further excavation. The operations took place in two phases. The first phase was initiated in 1981-82 and continued in every season up to 1984-1985. The second phase was started in 1988-89 and continued in the next two seasons up to 1990-91. The first phase of excavations was aimed at establishing the three major building phases of the cells that Dikshit mentioned in his excavation report and discovering the information of early levels. But in the second phase the works were confined to clear the cultural debris from the courtyard of the monastery. After a long gap a small-scale excavation was conducted in the temple area and nearby courtyard in 2007-08.

Architecture:

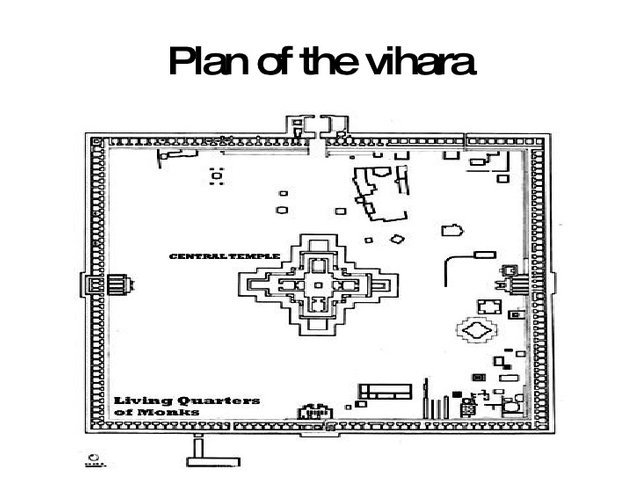

Pre-1971 expeditions have revealed the architectural remains of a vast Buddhist monastery, the somapura mahavihara, measuring 274.15m N-S and 273.70m E-W. This gigantic establishment with surrounding 177 monastic cells, gateways, votive stupas, minor chapels, tank and a multitude of other structures for the convenience of the inmates, is dominated by a central shrine, conspicuous by its lofty height and architectural peculiarities. It is distinguished by its cruciform shape with angles of projection between the arms, its three raised terraces and complicated scheme of decoration of walls with carved brick cornices, friezes of terracotta plaques and stone reliefs.

The monastery The entire establishment, occupying a quadrangular court, has high enclosure walls, about 5m in thickness and from 3.6m to 4.5m in height. Though the walls are not preserved to a very great height, but from their thickness and massiveness it can be assumed that the structure was storied commensurate with the lofty central shrine. In plan it consists of rows of cells, each approximately 4.26 x 4.11m in area, all connected by a spacious verandah (about 2.43 to 2.74m wide), running continuously all around, and approached from the inner courtyard by flight of steps provided in the middle of each of the four sides. There are in all 177 cells, excluding the cells of the central block in each direction; 45 cells on the north and 44 in each of the other three sides. The central block on the east, west and south sides is marked by a projection in the exterior wall and contains three cells and a passage around them, while in the north there stands a spacious hall. In the monastic cell No. 96 three floors have been discovered. Here the level of the last one (upper) is within 30cm from ground level, that of the second 1m, while the third (lowest) is about 1.5m from the surface.

It appears that this sequence has been generalised in all the cells of the monastery. However, the top most floors were removed while the second floor has been preserved. It is interesting to note that over this floor ornamental pedestals were built in as many as 92 rooms. Originally the main purpose of the rooms was to accommodate the monks of the Vihara, but the presence of such a large number of pedestals in the rooms indicates that they were used for worship and meditation in later construction phase. Besides the main gateway to the north, there was a quadrangular subsidiary entrance through the northern enclosure near its eastern end. There was no arrangement of ingress on the southern and western sides, but possibly a small passage in the middle of the eastern block was provided for private entrance. Apart from the central temple in the courtyard of the monastery there are many other small building remains, which were built in different phases of occupation. The important ones are a number of votive Stupas of various sizes and shapes, a model of the central shrine, five shrines, kitchen and refectory, masonry drain, and wells. Still there are some structures whose features could not be ascertained. The miniature model of the central shrine is located in the south of the central block of eastern wing of the monastery. In this model the plan has been perfected and made more symmetrical. Another important structure in this area is a flight of stairs, 4m in width, projecting for a distance of 9.75 m towards the courtyard of the frontage of the central block of the eastern wing. The last 6 steps are covered with stone blocks. In the southeastern part of the courtyard, near rooms 73 and 74, there are five shrines of varied shapes with a highly ornamented super-structure and a plan with a number of projections in which bold torus and deep cornice mouldings are prominent. The most interesting thing in this group is a structure showing the shape of a 16-sided star. All the shrines are enclosed within a compound wall. To its north there is a big well with the internal diameter of 2.5m.

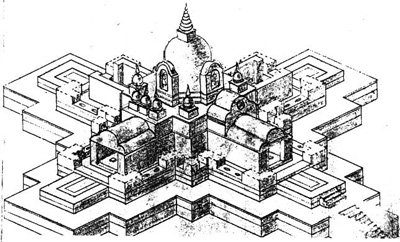

The kitchen and the long refectory hall (bhojanashala) of the monastery are also situated in this area. A masonry drain in between the refectory and the kitchen has been traced to a length of over 46m northward. To its west there are three large wells in a row, which probably used to serve both the kitchen and refectory. There are some important structures enclosed within a regular brick wall that runs from the verandah against rooms 162 to 174 (in the northwest part of the courtyard). There are rectangular weep-holes at regular intervals through the enclosure wall, so that the water may flow out from inside the enclosure. The most important structure in this area is a square brick structure in which the lower part consists of three channels separated by walling and closed on the top by corbelled brick work; the purpose of the corbelled channels is not clear. Further west there is a well preserved well. A lofty shrine, the central temple, occupies the central part of the vast open courtyard of the monastery, the remains of which is still 21m high and covers 27sq.m of area. It was built on a cruciform plan which rises in three gradually diminishing terraces. The shape of the terminal structure is still unknown to us. A centrally placed hollow square right at the top of the terraces provides the moot point for the conception of the whole plan of the spectacular form and feature of this stupendous monument. In order to relieve the monotony and to utilise the colossal structure to serve its basic purpose, provision was made in the second as well as in the first terrace for a projection, consisting of an ante-chamber and a mandapa on each face, leaving out a portion of the whole length of the square at each of the four corners. The ambulatory passage with the parapet wall was made to run parallel to the outline of this plan. This arrangement resulted in a cruciform shape with projecting angles between the arms of the cross. An enclosure wall strictly conforming to the basement plan, with only a slight deviation near the main staircase, runs round the monument. There is ample evidence that this complete plan, from the basement to the top, along with different component elements, belonged to a single period of construction, but the later repairs, additions and alterations did not fundamentally affect the general arrangement and plan.

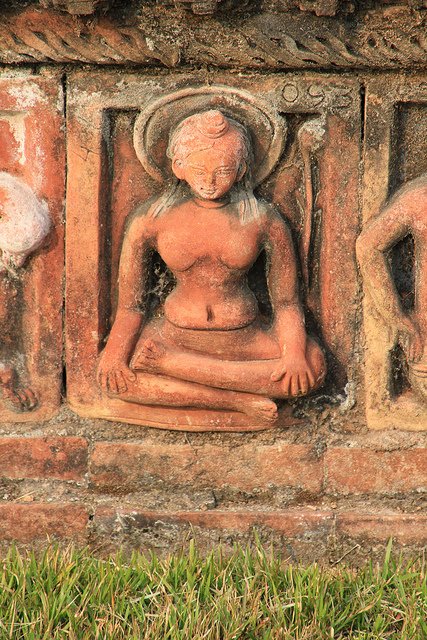

The basement wall of the temple is embellished with 63 stone bas reliefs which were inserted at most angles of the projection and at intervals in specially built recesses in the middle. The walls of the temple were built of well-burnt bricks laid in mud mortar. The plainness of the walls is relieved on the outer face by projecting cornices of ornamented bricks (twisted rope, chess board pattern, stepped pyramid, lotus-petal etc.) and bands of terracotta plaques, set in recessed panels, which run in a single row all around the basement and in double rows around the circumambulatory passage in the upper terraces. The temple-type at Paharpur has been frequently described as entirely unknown to Indian archaeology. The Indian literature on architecture, however, often refers to a type of temple, known as sarvatobhadra - a square shrine with four entrances at the cardinal points and with an antechamber on each side (chatuhshala griha). The temple at Paharpur, as now excavated, approximates in general to the sarvatobhadra type.

Structures outside the monastery area :

An open platform measuring 32m x 8m is situated at a distance of about 27m from the outer wall of the southern wing. It runs parallel to the monastery. It stands about 3.5m above the adjoining ground level and is accessible from a raised pathway across room 102. This gangway is 5m in width. In between the gangway and the wall of the monastery there is a vaulted passage running parallel to the wall probably for the free passage of people outside the enclosure from one side to another. Its vaulted construction is of utmost importance. To our knowledge, it is one of the earliest and very rare examples of this type of construction, proving that vaults were known in ancient India before the advent of the Muslims. The entire southern face of the platform is marked with a series of water-chutes, each 30 cm in width and 1.30m in length occurring at interval of 1.2m. The channels are provided with fine jointed brickwork. It was used probably for the purpose of both ablution and toilet. Bathing ghat There is a bathing ghat at a distance of 48m from the outer wall of the monastery towards the southeastern corner of the monastery. It is not parallel to the south wall of the monastery, but is slightly inclined towards the north. On either side of it there is a parallel wall paved with brick-on-edge and concrete. The head of the ghat is laid with huge stone blocks along with brickwork, 3.6m in length. It descends in a gradual slope to 12.5m, where occurs a band of lime stone slabs. The bed of the ghat is also covered with sand which shows the existence of a stream close by. A tradition in relation to the ghat is still current among the local people that Sandhyavati, the daughter of a king named Mahidalan, used to bathe at the ghat every day and she is supposed to be the mother of Satyapir through immaculate conception. Accordingly this is known as Shandhabati's Ghat.

Gandheshvari temple to the southwest of the ghat at a distance of about 12.2 m there is an isolated structure locally known as the Temple of Gandheshvari. The lotus medallion and bricks with floral pattern used in the front wall as also the mortar used between the joints of bricks sufficiently indicate that this building was erected during the Muslim period. It is a rectangular hall measuring 6.7m x 3.5m each side with an octagonal brick pillar base in the centre. There is a projection in the middle of the western wall which contains a small room, about l.5m square. It was used as a shrine and the four small niches on the sidewalls contained other objects of worship. In front of the door there is a circular platform, 7.3m in diameter with a brick-on-edge floor.

Post-Liberation excavations Apart from confirming Diskhit's findings in the cells, the post liberation period excavations brought to light two new unexpected facts. Firstly, the remains of another phase of the monastery, probably the monastery of an earlier period, was discovered below Dikshit's original (?) monastery. From the newly exposed evidence it appears that in the earlier phase the monastery was of the same size and the alignment of the enclosure wall and front wall was also the same. They used the original monastery for quite some time and subsequently removed the earlier floors and destroyed the earlier partition walls, and built new ones and thus they changed the arrangement of cells. In course of this reconstruction either at places they entirely destroyed the earlier partition walls and built completely new ones or they removed the earlier ones at their upper levels and kept the basal parts undisturbed over which they built the new ones. The earlier cells measured 3.96m internally. It clearly indicates that cells of the original monastery were larger than those of the upper monastery or k n dikshit's first phase monastery. Thus in later periods the number of cells was increased. Secondly, in some limited areas (north-east corner of the monastery, northern half of the eastern wing and north-eastern side of the central shrine) the remains of structures (brick walls and brick paved floor, terracotta well) and cultural objects (a terracotta head of Gupta period, huge number of ceramics) were brought to light underlying the monastery as well as the temple. Alignments of the walls bear no relation with those of the monastic plan or central temple. Due to very restricted exposure of these remains their nature could not be ascertained. It is worth noting that Dikshit discovered 3 occupation periods (floors) in the monastic cells and 4 occupation periods in the central temple. The recent excavations have discovered one more period in the monastery. Hence total 4 periods of the monastery correspond with those of central temple. Now, the question arises: which monastery did Dharmapala build? Is it the recently exposed earlier monastery or the monastery discovered by Dikshit? Here it is interesting to note that, Dikshit believed that originally there was a Jaina Monastery at Paharpur of which no traces have survived. The Somapura Mahavihara founded by Dharmapala in the end of the 8th century would then have succeeded this Jaina institution. Many subsequent authors have accepted Dikshit's hypothesis. Therefore, it could be suggested now that these recently discovered remains underlying the monastery excavated by Dikshit belong to this former Jaina establishment. However, the assertion of it shall have to await further extensive excavation inside and outside the monastic complex.

Movable objects :

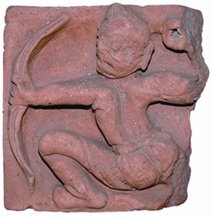

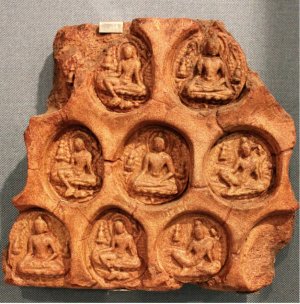

Among the movable objects discovered from the site the most important ones are stone sculptures, terracotta plaques, copper plate, inscriptions on stone columns, coins, stucco images and metal images, ceramics etc. Stone sculptures As many as 63 stone sculptures were found fixed in the basement of the temple. All the images represent Brahmanical faith excepting the only Buddhist image of Padmapani. It appears rather strange that such a large number of Brahmanical deities were installed in this grand Buddhist establishment. The occurance of Brahmanical sculptures in a Buddhist temple indicates that they were gathered from the earlier monuments at the site or in the neighborhood and fixed up in the main temple. These sculptures belong to different periods and can be classified into three distinct groups with respect to their style and artistic excellence. In the first group a considerable number of sculptures depict scenes from the life of krishna. There are some other panels, which depict the most popular themes of the Mahabharata and Ramayana and various other incidents from daily life of the rural folk. Their features and appearances are heavy and sometimes crude, without any proportion or definition of form. Though the art is technically crude and imperfect, but its social content is intensely human, highly expressive of liveliness, and therefore artistically significant. Despite a general heaviness all through in the sculptures of the second group, there are some panels which are marked by lively action and movement. Thus it is a compromise between the first and third group, which maintains the eastern Gupta traditions. The soft and tender modelling, the refinement and the delicacy of features, which are generally associated with Gupta classicism, mark the third group. Besides, there is a huge difference in attitude, subject matter, temperament and general technique between the first group and the other two groups. The sculptures of the other two groups generally depict cult divinities conforming to the dictates of the Brahmanical hierarchy. The stones used in them are greyish-white-spotted sandstone or basalt. Of all the loose stone images found in the excavations the most interesting is the fragmentary image of Hevajra in close embrace with his Shakti or female counterpart. Terracotta plaques play the most predominant part in the scheme of decoration of the walls of the temple. There are more than 2,000 plaques that still decorate the faces of the walls and about 800 loose ones have been registered. Majority of these plaques is contemporaneous with the building. No regular sequential arrangement has been followed in fixing these plaques on the walls. The sizes of the plaques vary in different section of the walls. Some are unusually big, measuring 40 x 30 x 6 cm and some are manufactured in a special size of about 18 square. cm, but most of them are of a standard height, measuring 36 cm x 22/24 cm. The representations of divinities of hierarchical religion are few and far between. The Brahmanical as well as the Buddhist gods are equally illustrated in the plaques. They are the principal varieties of Shiva and other Brahmanical gods like Brahma, Visnu, ganesha and Surya. Buddhist deities, mostly of the Mahayana School, including Bodhisattva Padmapani, Manjushri and Tara are noticed here and there. Well-known stories from the Panchatantra are represented with evident humour and picturesque expressiveness. The fancy and imagination of the terracotta artists at Paharpur seems to be revealed mostly in the various movements of men and women engaged in different occupations. The artists were fully responsive to their environment and every conceivable subject of ordinary human life finds its place on the plaques. Similarly animals - snake, deer, lion, tiger, elephant, boar, monkey, jackal, rabbit, fish, and duck goose - have been presented in their typical actions and movements. But the representations of the flora are comparatively poor. The lotus and the common plantain tree are represented in the plaques. It appears that this art must have been very popular in Bengal and through these plaques we get a glimpse of the social life of the people of that period. Inscriptions discovery of an inscribed copperplates and some stone inscriptions has helped us to determine the chronology of the different periods. The copperplates found in the northeast corner of the monastery is dated in 159 Gupta Era (479 AD). It records the purchase and grant by a Brahman couple of a piece of land for the maintenance of the worship of Arhats and a resting place at the Vihara, presided over by the Jaina teacher Guhanandin. This Vihara, which was situated at Vatagohali in the 5th century AD, must have been an establishment of local celebrity. It is worth mentioning here that the same name Vatagohali is found on a mutilated copperplate found at Baigram dated 128 GE (448 AD). The mention of the name Vatagohali in a record from Barigram, which is about 30 km to the north of Paharpur, indicates that the two places Vaigrama and Vatagohali may not be far away from each other. The Guhanandi Vihara at Vatagohali must have shared the fate of other Jaina establishments in Pundravardhana, when anarchy reigned supreme in Bengal in the late 7th century or early 8th century AD. At last peace was established and the Pala Empire was securely founded in Bengal in the 8th century AD and dharmapala at Somapura established a magnificent temple along with a gigantic monastery. Dikshit believes that the monks in the new Buddhist Vihara might have been given the royal permission to appropriate the land belonging to the Jaina Vihara and kept the original charter in their possession. According to him 'this supposition can alone, explain the find of the plate among the ruins of the Buddhist Vihara'. A number of stone pillar inscriptions were discovered from the site, which contain the records of the donation of pillars referring to either Buddha or the three jewels. The dates assigned to them belong to 10th and 12th century AD. All the donors have names ending in garbha, viz, Ajayagarbha, Shrigarbha and Dashabalagarbha, excepting one which shows a fragmentary record of some person whose name ended in 'nandin'. It is possible that these indicate continuity or succession of monks at Paharpur Vihara. Stucco A few stucco heads have been recovered from Paharpur, but this art was not as developed as in the Gandhara period. The common feature of all the Buddha heads found at Paharpur is the protruding eyelids and in some of them the hair is shown in ringlets. Metal images Only a few metal images have been found. The ornamental image of Hara-Gouri, a standing naked Jaina and the bronze figures of Kuber and Ganesh are the only important images that have been discovered at Paharpur from pre-Bangladesh period excavations. But the post-liberation excavation (1981-82 precisely) discovered the torso of a large and highly important bronze Buddha image. Due to damage by fire only the upper half down to the thighs has been preserved. However, it is still possible to make out that the figure once represented the Buddha in a standing posture. The surviving part of the image measures roughly 1.27m, so that total height of the original must have been about 2.40m. In view of its style and the layer in which the bronze was discovered the sculpture can be attributed to about the 9th or 10th century. The only other known bronze Buddha figure from about the same period and of roughly equal size is the famous image from Sultanganj in Bihar, now in the Art Gallery of Birmingham Museum. Coins As many as five circular copper coins have been discovered from a room close to the main gateway complex of the monastery. Of them three are of a unique type showing a rather clumsily depicted bull on the obverse and three fishes on the reverse. A silver coin belonging to Harun-ur-Rashid, the Khalifa of Baghdad bears the date 127 AH (788 AD). Another series of six coins issued by sher shah (I540-45 AD), two of Islam Shah (I 545-53 AD), three of Bahadur Shah (16th century AD), two of daud karrani, one of akbar (1556-1605 AD) and one of Sultan Hussain Shah Sharki of Jaunpur. All these coins are fabricated on silver excepting the last one, which is of copper. But we are not yet sure how these coins made their way into this vihara. Pottery The pottery discovered from the excavation at Paharpur was numerous and varied. Most of them belong to the middle or the late period roughly from the end of the tenth to the twelfth century AD. One class of ware, which may be attributed to the early Pala period (about 9th century AD). These are decorated with cross lines in the lower surface only or on the sides as well. Only a few large storage jars (one inside the other) were found in situ in some monastery cells. These large jars were set in the corner of the room by cutting the floor of the third period (Diskshit's second period) monastery. But no food grains or any other object was found in the jars. These were full of soil. A number of complete saucers could be recovered from the pre-monastic level. This pottery may be attributed to the pre-Pala period (c 6th to 7th century AD). Generally the pottery is well burnt to a red or buff green on which red slip was applied either in bands or on the entire surface except at the bottom. Almost all the vessels had a broad base and a protuberant centre while the large storage jars had a pointed or tapering bottom. Besides a number of vessels shaped like modern handis and spouted vases or lotas, there are also vessels with a narrow neck and mouth with a cylindrical body. A number of lids of pottery, dishes, saucers and lamps, which include a large variety of circular shell vessels with or without a lip at the rim near the wick, have been found. Other common antiquities are the terracotta crude female figures, the model of animals, parts of finials, dabbers of truncate cone shape, flat discs, sealings and beads of cylinderical shape. A number of ornamental bricks have been found in the pattern of the stepped pyramid, lotus petal, the chessboard, rectangular medallion with half lotuses etc. Preservation During the discovery of the monastery complex (1934) it was not in a very bad state of preservation. But within the last half a century its condition has deteriorated to such an extent that the very existence of this monument was threatened by some dreadful problems primarily due to water logging and salinity. The water logging was undermining the foundation of the central temple and contributing towards the decay and disfigurement of the terracotta and stone sculptures adorning the base of the temple. There was extensive salting or efflorescence all over the monument. The attempt made by the Govt. for preservation of the monument was insufficient to cope with the progressively deteriorating situation. So the Govt. of Bangladesh made an appeal to UNESCO in 1973 to safeguard this monument and the Mosque city of Bagerhat as part of World Heritage. Accordingly a Master Plan was prepared in 1983 by an international mission and both the sites were included in the World Cultural Heritage List in 1985. Subsequently a project was initiated in 1987 to implement the recommendations of the Master Plan, which continued in three phases and was completed in 2002. Under this project many issues including preservation of the structural remains of Vihara, drainage problem, construction of a museum and other infrastructures etc, were addressed. In order to arrest those partly solved problems as well as to face some other issues like tourism pressure, heritage management, safeguard the ancient landscape etc. Govt. has recently undertaken another project.

Integrity :

At present, only the archaeological boundaries have been established at the site, which could be regarded as the boundaries of the property. These boundaries include all required attributes to express its Outstanding Universal Value. However, the potential of mining activities in the vicinity of the property, as noted by the Committee at the time of inscription, highlights the urgency of establishing the boundaries of buffer zone for the property, which would need to take into account the natural environment surrounding the monument to maintain visual relationships between the architecture and the setting. Provisions for the management of the buffer zone need to be identified and implemented. Concerning to the material integrity of the property, the still uncovered part of the central shrine, as well as some terracotta plaques, are gradually deteriorating due to environmental element such as salinity and vegetal germination. This constitutes a threat to the physical integrity of the fabric and needs to be attended to.

Authenticity :

The authenticity of the property in terms of materials and substance and character has been compromised by interventions, including consolidation, substantial repair and reconstruction of the facial brickwork of the walls, which have prioritised presentation. In addition, the introduction of slat laden bricks and mortar as far back as in the conservation works of the 1930’s has further aggravated the situation. Vandalism, theft and increasing decay of some of the terracotta plaques have been the reasons for their removal from the main monument. The interventions can no longer be reversed so all future conservation and maintenance works shall focus mainly on the stabilisation of the monument to ensure that it is preserved in its present form. To ensure that authenticity is not further compromised, conservation policies need to be developed and implemented, to ensure that structural conservation meets current standards and promotes the use of traditional materials and local craftsmanship.

Protection and management requirements :

The whole complex, perimeter along with lofty central shrine, lies within an area protected by the government and supervised regularly by the local office. National legislation includes the Antiquities Act (1968, amended ordinance in 1976), Immovable Antiquities Preservation Rules, the Conservation Manual (1922) and the Archaeological Works Code (1938). Management and conservation of the World Heritage property and other related monuments in the vicinity is the responsibility of the Department of Archaeology. Besides, for the regular maintenance of the site, the responsibilities of the site management is carried by an office of the custodian under the overall supervision of a regional director guided by director general of the Department of Archaeology, People´s Republic of Bangladesh. A comprehensive management plan including conservation policies and provisions for a buffer zone will be drafted under the project "South Asia Tourism Infrastructure Development Project- Bangladesh portion 2009-2014". Adequate human, financial and technical resources will need to be allocated for the sustained operation of the identified management system and for the continuous implementation of the conservation and maintenance plans so as to ensure the long term protection of the property.

The Importance of Somapura Mahavihara:

The Somapura Mahavihara shows the traditions in this region during the Pala dynasty. It indicates the architectural capability of the people of this region in the ancient period. It is also a significant sign of the existence of Buddhist religion and the practice of Buddhist culture within this region.

Major Attractions of Somapura Mahavihara :

In this ancient architecture, you will find Terracotta Plaque in the walls especially at the base of the temple which is very attracting. You will also find Balrama Stone, Buddist God Havjara with Sakti stone and a bronze sculpture of Buddha. Other statues of stones include Chamunda, Standing Seetala, Keerti, Gouri, Visnu, Nandi, Sun, and Mansaha statue of claystone.

Nearest Tourist Attractions:

There are many famous tourist spots nearby which you can visit at the same time. The most prominent nearby tourist spot is Mahastangarh archaeological site which consists a lot of ancient remnants. The other major tourist attractions include Bairagir Bhita, Khodarpatar Bhita, Parasuramer Prasad, Mankalir Dhap, and Govinda Bhita etc.

Transportation and Communication:

One can go to Somapura Mahavihara, Naogaon from Dhaka by Bus. The tourist spot is about 282 kilometers far from Dhaka and may take up to 6. 5 hours to reach there by bus through Panchagarh- Bznglabandha highway. The route shall be Dhaka- Savar- Chandara- Tangail- Jamuna Bridge- Bogra- Naogaon- Badalgashi and finally Paharpur.

One can also visit this spot through air route. A lot of local Airline companies give special packages to visit this tourist spot. In this case, the airplane will land in Hazrat Shah Makhdum Airport, Rajshahi. From there the visitors will give to go to Naogaon by bus or car.

Hotels, Accommodations and Foods:

There are many hotels and restaurants near the Somapura Mahavihara. Some of them include Archaeological Rest House, Motel, and Restaurant of Bangladesh Parjatan Corporation.

Location of Sompura Mahavihara

Sompura Mahavihara

Rajshahi, Naogaon- 6500

282 kilometers away from the capital, Dhaka.

Somapura Mahavihara in Paharpur, Badalgachhi Upazila, Naogaon District, Bangladesh. It is 5 km west from Jamalganj railway station in the greater Rajshahi district, and it is important and the largest known monastery south of the Himalayas and Buddhist viharas in the Indian Subcontinent and archeological spot.

Information for Traveler:

Sompur Paharpur Bihar is about 282 km by road from Dhaka, and it will need about 6.5 hours to arrive at Paharpur by bus/taxi/private. From Dhaka, the direction shall be Dhaka – Savar – Chandra – Tangail – Jamuna Bridge – Naogaon – Badalgachhi – Paharpur

Place / Location / Area / Other important Notes:

Division-Rajshahi

District -Naogaon

Upazila-Badalgachhi

282 km from Dhaka

Travel from Dhaka: Mainly bus and private car

Postal code Badalgachhi-6570

Gallery:

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Somapura_Mahavihara

http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Somapura_Mahavihara

Congratulations @uniqe-creation! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPthanks