Leisure Patterns in middle-class Victorian England 1850-1900

image source

During the nineteenth century many rapid changes were taking place in Victorian England regarding the pursuit and patterns of leisure, some innovative and appreciated, others despised or mourned for their demise. Lobbyists had succeeded, at least in part, in stamping out sports of ‘ill-repute’, most involving violence against animals; the Temperance movement slowly brought sobriety to many places; and the evangelists sought to inspire good morals and decency in the community. The Industrial Revolution saw the creation of new jobs and soon urbanised the majority of people. Trade Unions followed, pushing for better conditions which included less stringent working hours and so more time for leisure. The success of industrialists spread to include many others in the more ‘respectable’ trades, and the advent of a new social class between the aristocracy and the workers – the middle-class – whose more determined members struggled to unify a group of people from differing backgrounds. These people sought to do that, in part, by the introduction of leisure-time activities which would be both ‘civilised’ and ‘educational’, while stamping down on those which were not.

dining out

image source

The period between 1850 and 1900 saw many new – and affordable - interests developed, but one problem the leisure-moralists had to contend with was keeping all these activities ‘respectable’; another problem was creating suitable replacement activities to satisfy the people who had had their traditional pursuits curtailed after pressure from the moralists. It was also seen as a mission to achieve the reshaping of the working-class into a more respectable and moral societal class. The problems the middle class found with leisure patterns between 1850 and 1900 in Victorian England were ones of change, and development, resistance and defiance, and it was through determination and perseverance that they affected the changes that occurred and finally found the respectability they were craving.

tennis party, at Wimbledon

image source

Respectability was what many members of the middle class were striving for. These were the people who developed and joined the temperance movement, the evangelical movement and any number of the ‘treat animals better’ movements. While their active constituents made up a small group overall, they still managed to effect some changes in society, and while it seemed like men were the driving force behind the new moral codes, they were just the ‘store-front’ and it was the women who were in control. They held the greatest influence over their children, instilling them with moral behaviour, dictating their social acquaintances and class values. The women set the standards of ‘propriety, decorum and morality’1 while the men put them into action, as there was still inequality in what women could and could not do, or where they could go and could not go compared to the men, according to the rules of society.

a day at the beach

image source

This recently-created middle class had to establish a niche for themselves in society, as ‘… the Victorian middle class was a social composite embracing men and women of widely differing conditions and experience’2 so trying to solidify themselves as a uniform class was one concept they had to battle with. Also, wanting to be seen as different to the aristocrats their more pious members generally saw as a lazy, vice-chasing class, promoting good work ethics was a way to do this. After all, their stratum was made up of shopkeepers, factory-owners, bankers and other so-called ‘decent’ trades. Their more determined and pious members decided that leisure-time should be promoted as a time of educational pursuits, such as visiting art galleries and museums, or the tamer amateur forms of the sports the aristocracy liked to play, such as cricket and tennis. ‘The problem of the Victorian ‘leisure revolution’ … was not the modern nightmare of an abyss of empty hours impossible to fill, but rather the difficulty of ensuring the proper exercise of moral responsibility in developing activities to occupy this free time.’3

croquet painting, by Winslow Homer

image source

As there was much crime in many areas of England, especially in metropolitan cities such as London, ‘two strategies of spatial control were employed by the middle class to eradicate the turbulent street culture’,4 and as many of those criminals could be found pursuing leisure activities such as any number of the blood sports, one counter-measure, introduced by Sir Robert Peel, was the formation of a police force to clean up the streets of ‘crime and disorder’ although it did take some time for this new system to be accepted. The other control was denying people access to the open spaces traditionally utilised for activities the ‘respectability’ sought by the middle class would not measure up to.

early Peelers

image source

By the 1850s the patterns of work had changed, thanks mainly to industrialisation, in England. Much of the rural lifestyle, with its annual holidays and events had disappeared as people had urbanised, following the work into towns and cities. There was also more pressure for land development as urban areas swelled and expanded, so an(other) enclosure movement saw the disappearance of common open spaces such as village greens, and therefore the loss of those areas traditionally used to celebrate their holidays, fairs, wakes and festivals; many in the lower classes resented what they saw as being entirely unfair and lopsided, as this poem shows:

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from off the goose.

When we take things we do not own

But leaves the lords and ladies fine

Who take things that are yours and mine.

If they conspire the law to break;

This must be so but they endure

Those who conspire to make the law.

Who steals the goose from off the common

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back.*

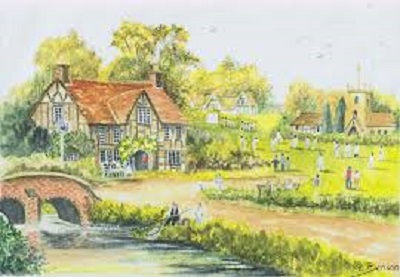

Cricket on the Village Green, by Gwendoline Benson

image source

In the 1860s there was a change to the structure of the working-week and hours, thanks to lobbying by the trade unions, expansion in types of jobs available, the evangelical movement’s campaigning, and industrial legislation; ‘… recreation grew to be accepted as a necessary amenity, a basic overhead in the maintenance of an industrial society.’6 Half-day Saturdays were born as the result of a new shorter working week for most people, and so now ‘… leisure constituted a problem whose solution required the building of a new social conformity – a play discipline to complement the work discipline that was the principal means of social control in an industrial capitalist society.’7 Taking advantage of the burgeoning railway system, thanks to the industrial revolution, was one way of expanding the options of leisure pursuits available, as the more sensible of the lobbyists realised that just taking away old leisure pursuits was not going to go well, unless there were new forms brought into their place. People still needed to do something during their time off. ‘In the new world of congested cities, factory discipline, and free enterprise … recreational life had to be reconstructed – shaped to accord with the novel conditions of non-agrarian, capitalistic society.’8

postcard depicting railway travellers

image source

The activities also had to be of better quality than what was previously available, but at an affordable price, so ‘as alternatives to the tavern, temperance reformers sought to provide “rational recreations” in the form of cheap concerts, public lectures, railway excursions, countryside walking expeditions, and coffee music halls … music, novel-reading, and parlor[sic] games ...’9 and in those public lectures of either self-improvement or entertainment ‘travellers, novelists, scientists, and even controversial phrenologists and mesmerists titillated their audiences with sugar-coated information. Alpine climbers were especially popular…’.10 As long as the ‘trendsetters’ of middle-class society deemed it worthy, then it was fine; and some of the most fervent trendsetters had also become evangelists.

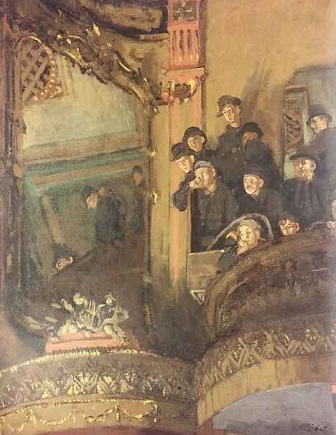

Gallery at the Old Bedford by Walter Sickert

image source

The evangelical middle-class movement made it one of their missions to curtail the baser leisure activities of the working-class. Their highly moralistic radars quivered whenever they discovered a football match, a wake, or a fair, and most certainly when they found the location of one of the abhorrent blood-sports favoured by those of all classes. William Booth was one dedicated middle-class evangelist, whose passion for change led him to found The Salvation Army with his wife; and for some of the women,

‘work among the ‘roughs and toughs’ was particularly fashionable from the late fifties among women of the upper middle classes, who frequently devoted their abundant spare time to proving that they could be angels not only in the house, but in shacks, dens and brothels as well. Such women were numerous among the mainstays of the ‘second evangelical awakening’ … ‘.11

Florence Nightingale, a coloured lithograph after Henrietta Rae

image source

Some went so far as to offer whatever aid they could to the men in active military service, constantly seeking to push the boundaries of what were acceptable pursuits for Victorian women, with Florence Nightingale being one of the most famous, and inspirational, of those ilk of women; although not all those within the middle-class of society were into do-gooding, temperance or restraint. One way they assured themselves a small break from the tedium of conformity was the development of seaside resorts, holidays and day-trips.

‘Holidays at the seaside provided a valuable safety valve, a legitimised escape from some of the more irksome constraints of respectability, and showed the more frivolous side of even the mid-Victorian middle classes. Roles at the seaside could be assumed, and even the lower middle-class male might put on airs, masquerading a new identity.’12

On the Shores of Bognor Regis by A. M. Rossi, 1887

image source

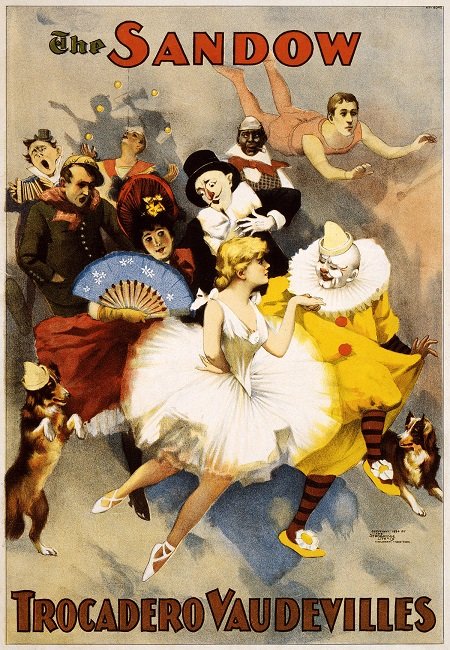

Another such relaxing and informal leisure-pursuit development was the Music Hall. ‘By 1865 there were thirty two music halls in London’13 peaking in 1878 with ‘seventy eight large music halls in the metropolis and 300 smaller venues.’14 It had evolved from an amateur operation to a commercial one by the 1880s. ‘Highly paid stars, agents, and promoters fully exploited the leisure market … the atmosphere was relaxed and gregarious; the skits were often lewd, the music inane, and the drink abundant.’15 Specialty acts seen on stage, such as magic, knife-throwing, fire-eaters, adagio, and talking dogs, were all way out of the scope of what was being sought as ‘respectable’ leisure pursuits by those wanting to control, define and refine the social ‘middle class’.

"A promotional poster for the Sandow Trocadero Vaudevilles (1894), showing dancers, clowns, trapeze artists, costumed dog, singers and costumed actors."

image source

To this end they did effect important and permanent changes within Victorian society’s leisure patterns between 1850 and 1900. The Temperance movement had sobered up many folk, breaking their bad habits of drinking which went hand-in-hand with other ‘vices’ such as watching and gambling on the more violent sports. The Evangelical movement went a long way to stamping out in many areas the more unseemly activities their dedicated members saw as not being respectable or suitable or of no educational benefit to society, while promoting and creating forms of leisure which they deemed to be totally respectable, suitable, and educational. Many of the activities and protocols their members developed enabled them to become a unified class in society, as the backgrounds of their members were quite varied, and they had to create a whole set of ‘rules’ to fit into their niche between the aristocracy and the working class of England. Despite the problems they encountered from many quarters, their determined members persevered with their changes and developments of their Victorian leisure pursuits; they’d adapted themselves to take advantage of the Industrial Revolution and all its enterprises, they’d adapted to the urbanisation and rapid growth of towns and cities, and the loss of rural communities and traditions, they’d created new pursuits and traditions, and had gained for themselves the mantle of respectability they’d been determined to create as the Victorian middle class.

A Summer's Day in Hyde Park by John Ritchie 1858

depicts the mixing of social classes

image source

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest, and I have broken up the larger blocks of text for easier reading.

References

1 Huggins, Mike J. “More Sinful Pleasures? Leisure, Respectability and the Male Middle Classes in Victorian England.” Journal of Social History. 33:3, 2000, p. 587. Retrieved 15 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3789212

2 Bailey, Peter. Leisure and Class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the Contest for Control, 1830-1885. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978, p. 90.

3 From “Time to Spare in Victorian England”, John Lowerson and John Myerscough, as quoted in: Leisure: An Extensive Study of the Victorian Era. Retrieved 14 April 2010, from: http://www.avictorian.com/leisure.html

4 MacMaster, Neil. “The Battle for Mousehold Heath 1857-1884: ‘Popular Politics’ and the Victorian Public Park” Past & Present 127, 1990, p. 117. Retrieved 10 April 2010, from: < http://www.jstor.org/stable/650944>

5 Boyle, James. “The Second Enclosure Movement and the Construction of the Public Domain.” Law and Contemporary Problems 66:1/2, p. 33, retrieved 11 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20059171

6 Bailey, Peter. Leisure and Class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the Contest for Control, 1830-1885. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978, p. 112.

7 ibid., p. 5.

8 Malcolmson, Robert W. Popular Recreations in English Society 1700-1850, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1973, as quoted in: Leisure: An Extensive Study of the Victorian Era. Retrieved 14 April 2010, from: http://www.avictorian.com/leisure.html

9 Leisure: An Extensive Study of the Victorian Era. Retrieved 14 April 2010, from: http://www.avictorian.com/leisure.html

10 ibid.

11 Anderson, Olive. “The Growth of Christian Militarism in Mid-Victorian Britain.” The English Historical Review 86:338, 1971, pp. 58-59. Retrieved 11 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/563655

12 Huggins, Mike J. “More Sinful Pleasures? Leisure, Respectability and the Male Middle Classes in Victorian England.” Journal of Social History. 33:3, 2000, pp. 592-93. Retrieved 15 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3789212

13 Music Hall. Retrieved 17 April 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_hall

14 ibid.

15 Leisure: An Extensive Study of the Victorian Era. Retrieved 14 April 2010, from: http://www.avictorian.com/leisure.html

Bibliography

Anderson, Olive. “The Growth of Christian Militarism in Mid-Victorian Britain.” The English Historical Review 86:338, 1971, pp. 46-72. Retrieved 11 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/563655

Anstey, F. ‘London Music Halls’ Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 82:488, 1891, pp. 190-202. Retrieved 16 April 2010, from: http://digital.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=harp;cc=harp;rgn=full%20text;idno=harp0082-2;didno=harp0082-2;view=image;seq=0200;node=harp0082-2%3A3

Bailey, Peter. Leisure and class in Victorian England: Rational Recreation and the Contest for Control, 1830-1885. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978.

Boyle, James. “The Second Enclosure Movement and the Construction of the Public Domain.” Law and Contemporary Problems 66:1/2, pp. 33-74, retrieved 11 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20059171

Farrant, Sue. “London by the Sea: Resort Development on the South Coast of England 1880-1939.” Journal of Contemporary History 22:1, 1987, pp. 137-162. Retrieved 14 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/260378

Huggins, Mike J. “More Sinful Pleasures? Leisure, Respectability and the Male Middle Classes in Victorian England.” Journal of Social History. 33:3, 2000, pp. 585-600. Retrieved 15 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3789212

Leisure: An Extensive Study of the Victorian Era. Retrieved 14 April 2010, from: http://www.avictorian.com/leisure.html

MacMaster, Neil. “The Battle for Mousehold Heath 1857-1884: ‘Popular Politics’ and the Victorian Public Park” Past & Present 127, 1990, pp. 117-154. Retrieved 10 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/650944

Music Hall. Retrieved 17 April 2010, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_hall

“Progress of Temperance” The British Medical Journal 2:1911, 1897, pp. 412-413. Retrieved 11 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20250977

Sandiford, Keith A. P. “The Victorians at Play: Problems in Historiographical Methodology.” Journal of Social History 15:2, 1981, pp. 271-288. Retrieved 17 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3787112

The Metropolitan Police. Retrieved 17 April 2010, from: http://www.victorianweb.org/history/police.html

Wellhofer, E. Spencer. “Two Nations”: Class and Periphery in late Victorian Britain, 1885-1910. The American Political Science Review, 79:4, pp. 977-993. Retrieved 14 April 2010, from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/195624

I’ll be honest, I cannot read this right now, so commenting first as a way to bookmark! But I’m a lover of historical romance and it annoys me to no end that all the mainstream popular authors write about the upper class. I want to read about the middle to lower... I actually wrote to an author once complaining and was disappointed to hear her assure me she does have a story of a woman in the lower class....who will be saved by some lord. Grrr...

Anyway, a quick glance over, and it looks like it will be an informative one and good quality since it’s coming from you!

Oh yes! I hear you on all the aristocracy-focused historical romance stories. It would certainly be nice to read otherwise. :)

This is a curation bot for TeamNZ. Please join our AUS/NZ community on Discord.

For any inquiries/issues about the bot please contact @cryptonik.

Another excellent essay raven. Such a good idea publishing them all to steemit too.

Thanks. :)

Who knew, back then, that they'd find an audience ...

Lol. This is true.

Just think, if you had done that much work today intending it only for a post, considering the time spent researching it, writing and editing it,

All for the few dollars you will be paid for it.

The people keep asking for quality posts, you give them one, and get peanuts.

Another person will copy paste something and get mega bucks for it, makes you wonder where the justice is.

At least your work is there for ever, or so they say.

It is a topsy-turvy world, to be sure.