From Belgium with love: how pigeons were used for espionage during WWII

During the Second World War, the British intelligence services used pigeons to obtain information from the occupied continent. A new book shows which important role a Belgian espionage group played in this. Three members of the group paid for it with their lives.

When we talk about espionage in the Second World War, we often think of people who send messages to London in the form of morse code, in a hidden room with a portable radio in a suitcase. It will probably surprise that information was then also transmitted according to an ancient but proven method: carrier pigeons.

In Great Britain, the National Pigeon Service, with the help of local pigeon fanciers, ensured that thousands of pigeons were available for the intelligence services.

Occasionally, when a secret agent was dropped, he had a pigeon with him. A radio device was often heavier, more clumsy, less discreet and even less reliable than a pigeon. Once the animal was released, it almost always found its way home. The animal was easier to carry, more discreet and often even more reliable than a radio station.

The "Falcon Destruction Unit" from MI5, the team that wanted to kill hawks on the British cliffs to protect returning pigeons

Even though pigeons had their own disadvantages. They could be victims of bad weather or birds of prey. For this reason, in some English coastal areas, raptors were systematically liquidated by game wardens during the war. On the other hand, the British bred hunting falcons to hunt for "suspect" pigeons that flew from England to the continent, although they never seem to have found one pigeon with messages for the enemy.

A special activity was Operation Columba. Pigeons were dropped in occupied territory in the hope that the honest finders would send them back accompanied by information. Certainly at the beginning of the German occupation of Western Europe, the British lacked informants on the continent, while of course they wanted to know more about the preparations for a possible German invasion of Great Britain.

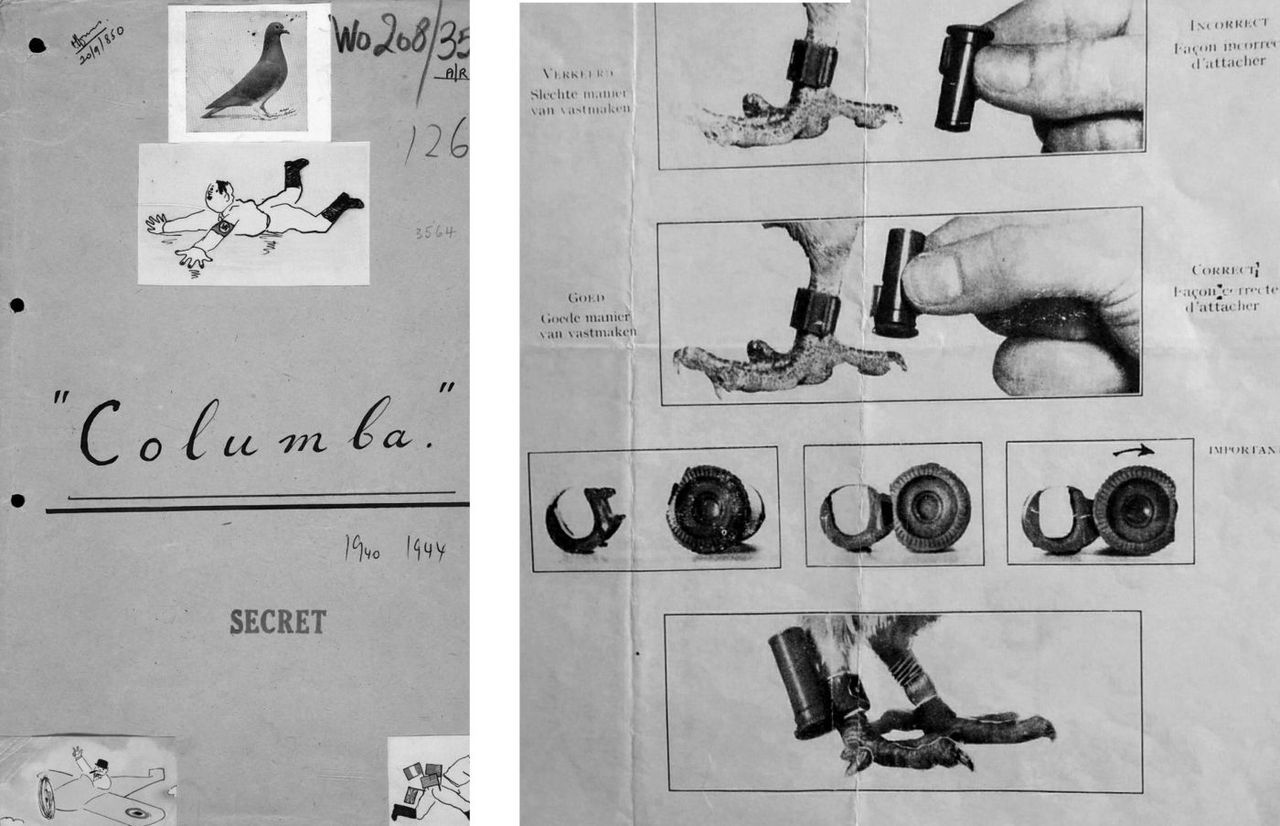

Cover of the 'secret' Columba file (The National Archives, wo208 / 3560) and instructions on how to attach a tube with messages to a pigeon's foot

The pigeons were dropped from an airplane in a box with a parachute. There was also a letter for the finder with a questionnaire, a piece of paper and a whole manual. The finder was asked to fill in the form and to attach it to the pigeon's leg, after which he could let go the animal.

On the form, you were able to provide information about the presence of German troops in the area, German installations, transports, etc., as well as the mood of the population among the occupying forces. That information gave the British intelligence services a clearer picture of what the enemy was doing.

Left, Brian Melland, the head of Columba at MI14. Right, a RAF pilot with two boxes for pigeon transport

The use of pigeons, especially in Belgium and northern France, were reasonably successful. The large majority of the pigeons, however, never returned. They were not found, or the finders didn’t dare to send them back or chose to eat the pigeon ... The pigeons that were found, usually brought useful information.

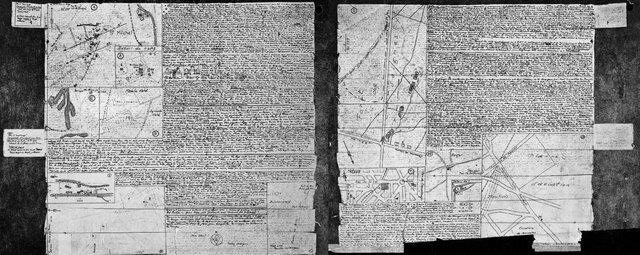

More than valuable was the information that was brought on 12 July 1941 by a pigeon that had been dropped in the vicinity of Lichtervelde in West Flanders (Belgium) seven days earlier. The light sheets of rice paper were filled with detailed information and precise drawings of military installations. The text not only described the installations, but also reported the consequences of a recent bombardment on Brussels and even gave recommendations on where there could still be bombed.

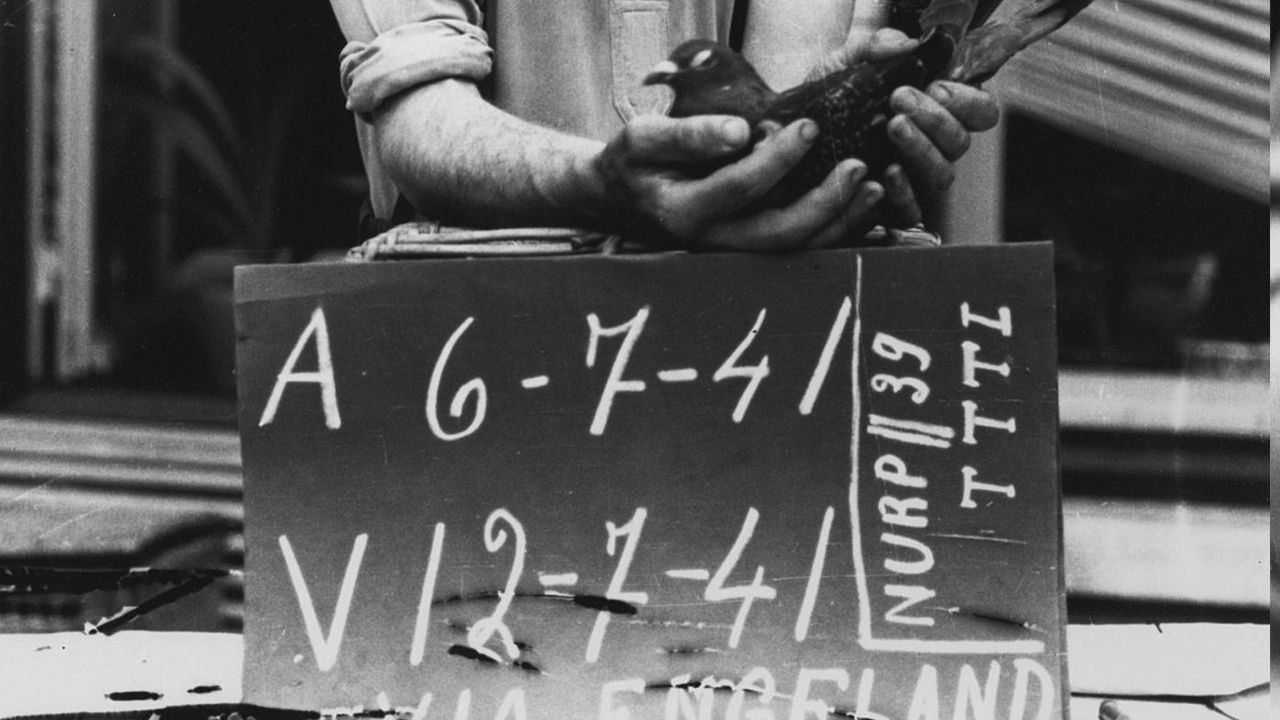

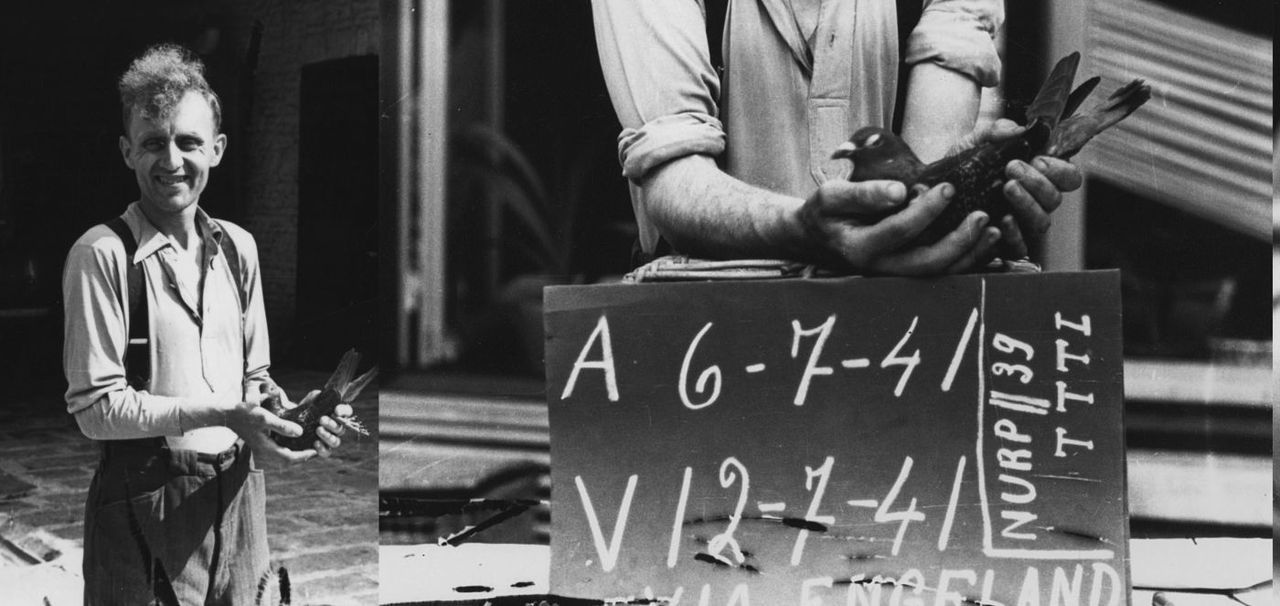

Michel Debaillie and the pigeon that was dropped in Lichtervelde, with day of arrival and departure. The people involved were so excited about the event that they also photographed everything, which was not without risk; but the photos did not fall in German hands.

The information of this one pigeon was so precious to the British, that Prime Minister Churchill himself got the notes.

The pigeon was sent back by a group that called itself 'Leopold Vindictive', a symbolic name. Leopold referred to King Leopold III and the 'Vindictive' was a British warship that had been used in 1917 for attacks on Zeebrugge and Ostend (the bow of that ship can still be seen in the Ostend harbor).

Two of the rice paper sheets with a very fine handwriting (The National Archives, wo208 / 3560)

Behind that name were a group of men who knew each other well and spied for the occasion. The Debaillie brothers from Lichtervelde, who had taken care of the pigeon (one of them was pigeon fancier), their friend Hector Joye from Bruges and Joseph Raskin, a missionary from Scheut, the most striking figure from the companionship.

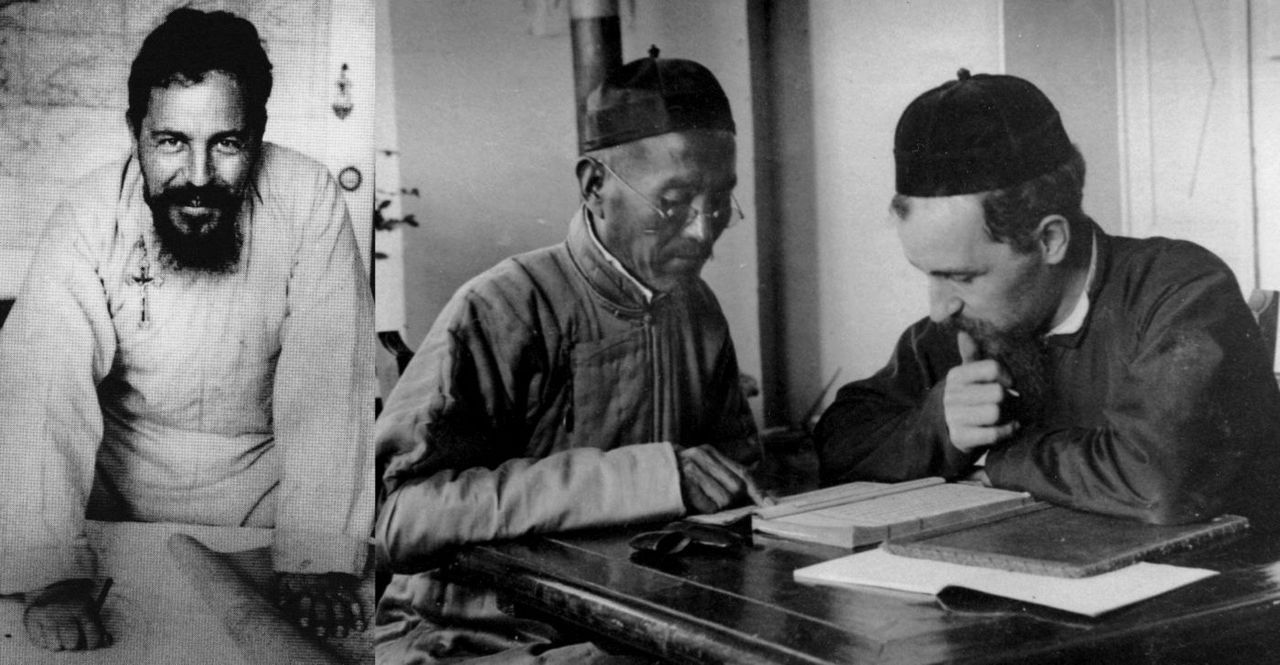

Raskin had done missionary work in China and learned Chinese calligraphy there. He was also a really good drawer. During the First World War he had made drawings of the frontline as an "observer" for the army. He was the author of the hyperfine handwriting.

The pigeon from July 1941 was the beginning but also the highlight of the activities of 'Leopold Vindictive'. On the notes the group had promised more information, asked for more pigeons and gave directions where it could be dropped. For many reasons, however, these new pigeons never came.

Joseph Raskin, at the right as a missionary in China

Father Raskin - who traveled throughout the country as a propagandist for the missions - therefore reached out to other resistance groups to send the information by other means - couriers or radio connections.

As a result, he made himself vulnerable, because these groups were sometimes infiltrated by informers from the Abwehr, German counter-espionage. In 1943 Raskin was arrested, followed by Joye and Arsen Debaillie, one of the brothers. All three of them would be sentenced to death and executed by the infamous German People's Court.

Hector Joye and his family, in conversation with Father Raskin

Writer Brigitte Raskin, a niece of Joseph Raskin, devoted a book to her remarkable uncle in 2005: 'The year of the magpie'. For his espionage activities, she relied mainly on the file the German prosecutor had put together about him.

Now, more than ten years later, the British journalist and spy expert Gordon Corera has made an entire study on the use of pigeons in the Second World War and in particular the 'Leopold Vindictive' group.