The sculpture of the late classical period draws from the past as well as from the future: portraits and tombstones depict the Greek ideal of sophrosyne - prudence, discipline, and restraint. Athletes appear in imperious and commanding positions (Stewart, 1991: 178), and in those times of profound political change, heroes are presented as an expression of virtue and perfection: with powerful, perfect bodies. The gods, on the other hand, are indifferent and distanced in their expression (Stewart, 1991: 178-180).

The increasing knowledge of anatomy, physiognomy, and geometry allows discreetly penetrating these areas into sculptural art, strengthens its destructive power and the recipient is forced to take a stand. While the treatment of the naked body has already been established in previous decades, the late classical period focused on improving details: anatomical structure, body and musculature and leads to the first depictions of sensuality in women (Boardman, 1964: 160). Hence the birth of a new direction in sculpture, whose representative is Praxiteles, and which was called - beautiful. (Estreicher, 1973: 131).

Praxiteles owes his popularity to this skill. His sculptures delicately engage the recipient, at the same time holding him at a distance. Aphrodite from Cnidus (about 340 BC) is considered the greatest achievement in sculpture of the late classical period. Made of Parisian marble, with gold-plated hair, jewellery and hydria, also fitted with a painted coat. Her body was a natural marble colour, or at best lightly coloured and her eyes were blue with a marked reflection of light. Presumably, this delicate polychrome became the reason for the low quality of the later, preserved copies of Aphrodite (two of them, the most faithful, are in the Vatican): plaster castings proved to be impossible because they could destroy the surface of the sculpture.

Praxiteles presents the goddess surprised during the bath - naked, slightly smiling, even submissive. The sculptor is the creator of the female act, which previously did not occur in Greek art (Estreicher, 1973: 132). Aphrodite, known in Cnidus as Euploia, purifies her body in the journey of Aegean described by Homer (Hymn to Aphrodite) (Stewart, 1991: 177-178). This sculpture is an important, if not decisive, step in the creation of a new way in which the ideal of divinity was presented. The majesty adequate of Phidias' works gives way to the narrative: we observe the deity in direct interaction with the world. Aphrodite - divine, in this world, but not of this world. Fertility goes hand in hand with another attribute: modesty perceptible in the goddess's reaction to the presence of an observer and the position of the right hand trying to cover the intimate parts, and Stewart (1991: 177) suggests that the observer is reduced to the role of a voyeur.

The sculpture, despite the fact that it occupies a space with the observer, retains the distance appropriate to the earlier cult performances. In this way, Praxiteles combines the old, with the modernity of the fourth century - constructing closeness with divinity, while not dethroning the goddess (Stewart, 1991: 178).

A similar dialogue is taken by Apollo Sauroktonos (Lizard killer). A young man leaning against a tree, in the next moment, like a photograph, he will immobilize the lizard climbing on the trunk with the help of a spike held in his right hand. A superficial look can give us a parodistic interpretation of the sculpture - Apollo fighting the dragon guarding Delphi. On the other hand, lizards in folk medicine were considered an anti-aphrodisiac. So could a teenage, dispassionate god of medicine look for a path to self-purification and renewal?

The double meaning (naive, folk for simple people and deep for the initiated) is a continuation of the dialogue between being in this world, but not being of this world; distance and presence. Other sculptures of Praxiteles can be understood similarly.

Artemis from Gabia is presented with a mantle, which he accepts from women (brides). Again in this work, the devotee and deity are united in a personal relationship.

The works of Praxiteles, apart from the beauty, were characterized by multi-colour. He employed an outstanding painter Nicias, who enriched sculptures with polychrome (Estreicher, 1973: 132). However, the colours differed from natural ones: hair, eyebrows, eyelids, lips were red.

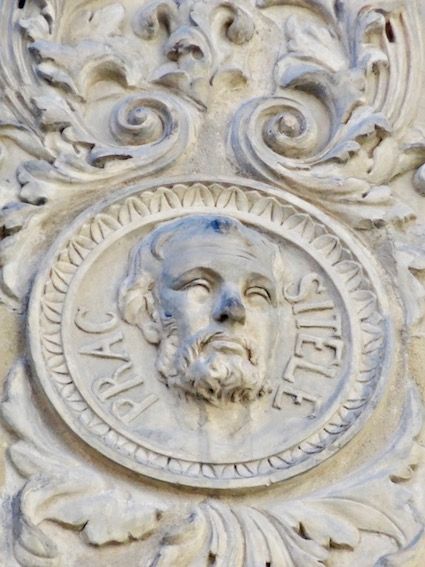

Born on the island of Paros around 395 BC Scopas had the finest sculpting marble at his disposal, but unlike Praxiteles, he chose bronze (Makowiecka, 1987: 111-112). The news about Scopas, which we have, comes mainly from written sources, few sculptures with debatable attribution and a few Roman copies. Like his masters, he did not work in one city but sculpted for Athens, Thebes, the cities of Peloponnese and the Hellenized cities of Asia Minor.

In the sculptures of Scopas, for the first time, we observe pathos (suffering, passion) contrasted with love and peace (Papuci-Władyka, 2001: 307). Athens owed him two sculptures of Erina, Megara - three sculptures of Eros, Himeros and Potos.

Potos, who we know in 40 copies, is the most 'Polycletian' in its style. Winged (as is known from Roman engravings), equipped with various attributes dependent on copies (phallos, lantern, thyrsos, etc.), he may have originally lean on Aphrodite, directing the attention of the observer through the rising slant of his body and raised head. As Plato (Phaedrus) writes, Potos, like Maenad, represents a kind of divine madness and how she wants to "free herself from the living grave we carry with us, from this prison that we call the body". Maenad and Potos are Olympic gods who maintain distance to humanity, but at the same time, they establish communication between these two worlds (Stewart, 1991: 184). The former ideal of balance and harmony is disturbed by expressionism (Estreicher, 1973: 133). Unfortunately, we know the sculptures of Scopas only from fragments and copies.

Scopas also worked in Boeotia, where Athena Tritonis (Thebes) was formed. He was one of several artists who decorated the famous Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (subsection III), where he was to decorate the eastern wall of the building. There are speculations that on his way back to Athens he worked on decorating the Temple of Artemis by sculpting the bottom drums of the columns.

In Ephesus, Scopas created a group of sculptures for a nearby grove - Ortygia, where, according to the local legend, Apollo and Artemis were born. Leto's goddess is presented with a scepter, and Ortygia holding divine twins. At that time, Marine Tiazos was also created - sculptures depicting the Nereids on dolphins, hippocampus, and tritons.

The image of the Raging Maenad (Dresden Museum) is the first classic record of the phenomenon of divine madness. The head and body of the figure are strongly twisted in opposite directions. With his hand grabbing the bock, he draws the observer into the vortex of her orgiastic, cleansing dance (Stewart, 1991: 184). The innovative presentation of ecstatic dance has so far been known only from vases from the 5th century BC. Through Maenad, we meet God - Bacchae shows all the symptoms of Dionysian possession and empathy (enthusiasmos). Blood lust (spargamos), effort to free oneself from the body (ekstasis), lack of control over the senses (ekphron) (Stewart, Greek Sculpture: 184).The last job of Scopas in Asia Minor is Apollo Smintheus - Mouse Exterminator. This image of the god was transferred to coins in later years. Apollo plays here in a similar way to Sauroktonos.The cult was present only in Asia Minor and did not appear in mainland Greece.

Scopas is credited with creating a new style of heroic sculpture, the best example of which is the temple of Athena Alea (345 BC) in Tegea. The temple reveals Scopas' great abilities in the field of sculpture and architecture. Fragments of heads from the federal altar located in front of the temple, as well as the sculptures of Asclepius (found in Piraeus) and Hygieia have survived to this day. These examples in the word represent the so-called "Scopas pathos". National content, unambiguously anti-Spartan, prevailed. The eastern metope and fronton show the deeds of the heroes of Tegea, including the hunt for the Caledonian Boar, in which Atalanta and her lover Meleager are led by warriors from all over Greece. The western façade showed the life of Telefos, the son of Heracles, from his birth in Tegea to the battle with Achilles in Myzya and the coronation of Telefos as king (Stewart, 1991: 183). The Telefos myth is an echo of conflicts waged by successive waves of Greek colonizers in Asia Minor. Various episodes of his life are also adorned with the inner frieze of the Pergamum Altar, and the people of this region identified their roots with Arcadians and Telefos.

The metopes survived only in fragments, similar to the figures of the fronton. Nevertheless, one can notice their intense relationship and spatial interaction. Massive bodies with extensive muscles play in space often going beyond the physical frame of the performance. Open mouth, wide nostrils, wrinkled foreheads - these expressive agents give emotion to the battle and passion to the heroes.

Scopas gained recognition thanks to the image of Aphrodite Pandemos in Elide - sitting on a galloping cap. Pliny says that the passionate statue of Aphrodite exceeded the statue from Knidos because it expressed the depth of emotion.

Scopas’ works were characterized by an individual style aimed at "reviving" the material and revealing emotions with the help of the shape of the figure and the modeling of the head.

Further travels of Scopas brought the rise of sculptures: Aphrodite to Samothrace, Heracles in Sicyon, Asclepius and Hygeia in Gortis in Arcadia, and Hecate in Argos. The sculptor gained recognition in his time and influenced the sculpture in the Hellenistic period when the features of his style were grounded and developed.

References

Images: sources linked below

- Papuci-Władyka, E. Sztuka starożytnej Grecji, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA, Warszawa, 2001

- Stewart, A. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration, Volume I: Text, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1991

- Estreicher, K. Historia sztuki w zarysie, PWN, Krakow, 1973

- Boardman, J. Sztuka Grecka, Wydawnictwo VIA, Toruń, 1964

- Makowiecka, E. Sztuka grecka – krótki zarys, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa, 1987

_(Louvre%2C_CA_1324).jpg)

Quite detailed and Through. Lovely post.

Really appreciate this thoughtful, intelligent post! I love getting to know the inner history behind these sculptures, and it’s so cool that you’re using steemit as a place to share!

Thank you for such kind words, I plan to have few posts about the changes that occurred at the threshold of Hellenistic era. Hope you will find them equally interesting.

Looking forward, for sure! :)

Your post is another great example of how Greece simply is "the cradle" of European culture and history. It looks you have a "elevated" passion for history and architecture.

Hi there, thanks, but you know... Romans (the whole Italian peninsula)also had their share of bringing wonders and spectacular inventions to this world ;)