Forty Years or Forty Days?

In Numbers 33, the itinerary of the Israelites from their departure in Egypt to their subsequent arrival in Canaan has been recorded as a catalogue of the Forty-Two Stations of the Exodus. These are the places where the Israelites halted on their long march to freedom. Traditionally, this journey took them forty years to accomplish. In some cases, they are described as encamping at a particular station for one or two nights before proceeding on their way. In other cases, they spent years at a single station before resuming their flight. In the Seder Olam Rabbah, which summarizes the rabbinical chronology of the Hebrew Bible, we read:

And it is written: “And they departed from Rameses in the first month, on the fifteenth day of the first month … Leaving Rameses, they journeyed through Succoth, then Etham, and finally came to Pihahiroth. That journey took three days. (Johnson 909-915).

They dwelt in the wilderness of Sinai ten days less than a full 12 months. It says: “And Moses wrote their goings out according to their journeys by the commandment of the LORD.” [Numbers 33:2] They left the wilderness of Sinai and came to the Graves of Desire [The Kibroth-Hattaavah of Numbers 11:34], dwelling there 30 days. (Johnson 1263-1270)

They left the Graves of Desire and came to Hazeroth and dwelt there seven days. (Johnson 1276)

They left Hazeroth and came to the wilderness of Paran. (Johnson 1280)

And it is written: “And the space in which we came from Kadesh-barnea, until we were come over the brook Zered, was thirty and eight years ...” [Deuteronomy 2:14] They were wandering to and fro 19 years and they dwelt in Kadesh Barnea 19 years. (Johnson 1295-1299).

In the model of the Short Chronology which I am following, the Exodus was a genuine historical event, but the journey from Egypt to Canaan did not take forty years:

The Exodus took place at the end of the Hyksos Period of Egyptian History, when the Pharaoh Ahmose I, founder of the 18th Dynasty liberated the country from foreign rule. The Hyksos were Assyrians and their empire was synonymous with the Akkadian Empire and the Middle Assyrian Empire.

The Exodus took place in the 8th century BCE. I have accepted as a working assumption the date of 763 BCE, which Charles Ginenthal suggested (Ginenthal 2010:542).

The House of Israel was not a great nation at this time, but merely the extended family of Jacob and their dependents. Jacob and his family had settled in Egypt a few generations before the Exodus, and by the time of the Exodus the House of Israel can hardly have numbered more than about 6000 people.

The Israelites did not wander in the desert for forty years. They had a very specific destination: Canaan. They may have followed a circuitous route to get there—the wherefore is explored below—but they did not dawdle along the way. The Wandering in the Desert lasted weeks or months at most.

In an earlier article in this series, I wrote:

A common mistake when interpreting an ancient text such as the Old Testament is to assume that each passage was written by a single author in a single sitting. It is, however, much more likely that the final text was the work of many hands spread over a considerable period of time, with each successive scribe burying the original story beneath a new layer of details and elaborations. The original story may have been a very short and simple tale that was transmitted orally for several generations before being written down.

The idea has occurred to me that the itinerary preserved in Numbers 33 may originally have been a list of the daily encampments of the House of Israel during the flight from Egypt to Canaan. Is it possible that the entire journey took not forty years but forty days?

How Long, O Lord, How Long?

How much ground did the Israelites cover during the Exodus? Obviously, that depends on what route they followed—and that is what I am trying to establish in these articles. Nevertheless, we can derive some ballpark figures from the traditional route and common alternatives.

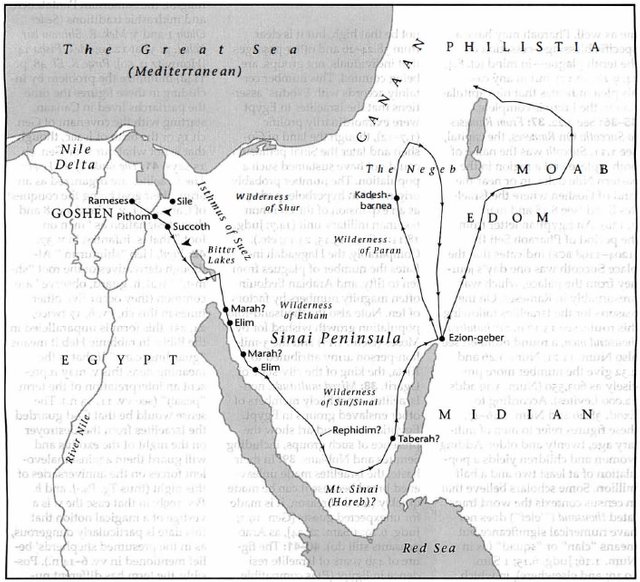

In the Jewish study Bible the following map depicts what the authors call a probable route:

This route is roughly 1300 km long. To cover such a distance in about 40 days would require an average pace of 30-35 km per day.

Another traditional route is depicted in a 17th-century engraving by Michel van Lochum:

At approximately 1000 km long, this route is somewhat shorter than the previous one. Such a distance could be covered in 40 days at an average pace of only 25 km per day.

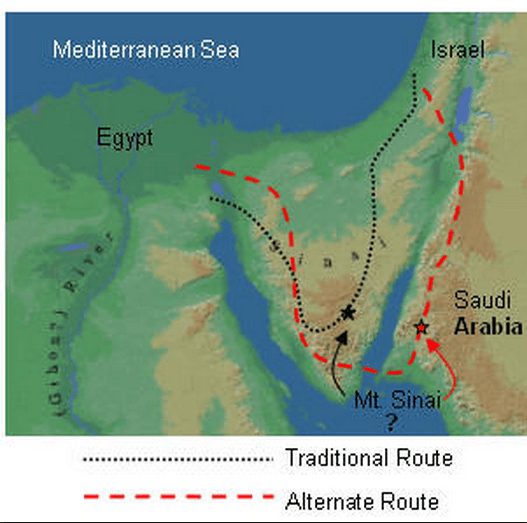

As an example of a non-traditional route, I chose the following from Knowing Jesus:

This route is even shorter—approximately 900 km, or an average pace of about 22 km per day.

Could a large body of migrating families cover 20-35 km per day for six straight weeks?

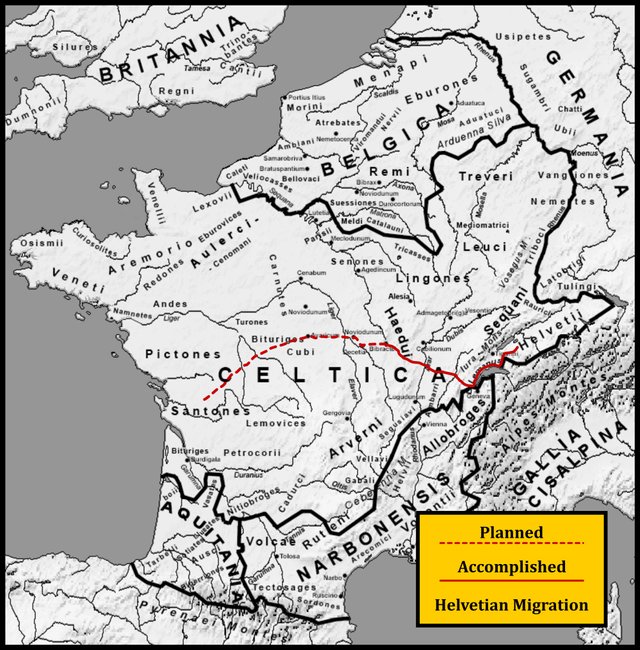

Migrations of entire nations were not uncommon in the ancient World. In Book 1 of his Gallic War, Julius Caesar describes how he prevented the migration of the Helvetii, a Celtic tribe, from their homeland in northern Switzerland to Charente in western Gaul—a distance of about 600 km. According to Caesar, the Helvetian nation and their allies numbered 368,000 people at the time (Caesar 21).

Historians estimate that while Roman Legions could cover as much as 75 km per day or more, a more realistic figure is 15-25 km, depending on the terrain and on the type and amount of baggage, or impedimenta, they were carrying (Thorne 29):

Marching with their packs and equipment was an important part of Roman military training. As a result, the Romans could make relatively rapid marches with their impedimenta. Caesar marched from Rome to Spain in 27 days although, according to Appian “he was moving with a heavily-laden army” [Appian, Civil Wars 2.15,104]. Mules did not necessarily slow the army down. Suetonius says Caligula moved so fast in his German “campaign” of 39 A.D., that in order to speed up their march, the Praetorian Guards tied their standards to their pack-mules “against their tradition (contra morem)” [Suetonius, Life of Caligula 43]. This shows that the mules could keep up with a Roman forced march, which is quite in keeping with the animal’s estimated march rate. Wagons, on the other hand, did slow an army down considerably. After the lucrative campaign against Galatia in 189 B.C., the Roman army, overloaded with booty, made barely five miles [8 km] a day. (Roth 296-297)

The mule travels relatively slowly, from 7.2–8 k.p.h. ... but this is compensated for by its ability to march continuously for ten to twelve hours. Estimates of daily travel rate vary from 40km ... to 80 km. ... per day. Forced marches were possible: 19th century U.S. Army mule trains sometimes traveled 130 to 165 km. ... in a day. The average mule’s carrying capacity can be reasonably estimated at 135 kg. ... for a distance of 50 km. ... per day, dropping to 20 km. ... per day in mountainous country. (Roth 206-207)

If Appian is to be believed, Caesar covered the 2000 km or so from Rome to Obulco (50 km east of Cordoba in Spain) in just 27 days—an average pace of about 75 km per day (Caesar 474). A later historian, Orosius (6:16:6), has Caesar cover the 1650 km from Rome to Saguntum in 17 days—an average speed of 97 km per day! See Raaflaub & Ramsey 5-11 for further discussion.

The Helvetii, on the other hand, are estimated to have travelled at a mere 8-16 km per day (Thorne 31). If 368,000 people could travel at this speed, how fast could a much smaller group travel? Perhaps as much as 20 km per day, but surely not as fast as Roman Legions.

So either the Exodus took more than 40 days, or the route was shorter than any of the routes that are usually proposed—or both. But in neither case is the required adjustment significant. 800 km in 42 days is an average pace of 19 km per day. I think that is not out of the question for a migrating body of 6000 people.

Setting Forth

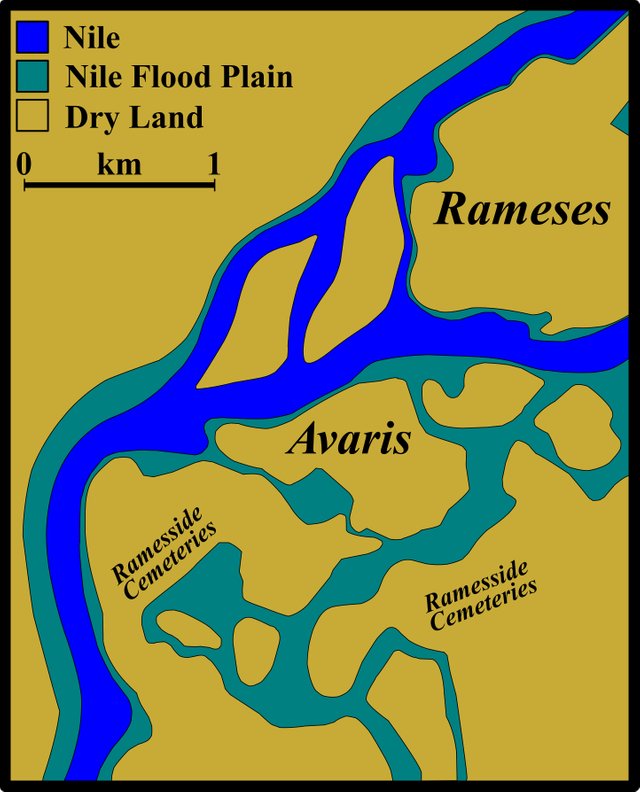

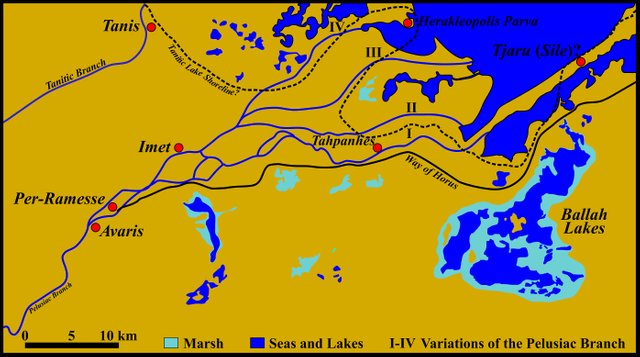

In the previous article in this series, I concluded that the first station, Rameses, referred to the area around the Hyksos capital of Avaris, on the site of which the later city of Per-Rameses was constructed. I also surmised that the Israelites set out for Canaan along the principal thoroughfare between Egypt and Palestine, the Way of Horus. This road runs roughly northeast from Rameses towards the Mediterranean Coast. I suggested that at some point the Israelites turned off the road and headed in a more southerly or southeasterly direction. If, however, each Station of the Exodus was only one day’s march from the previous one, this opinion may have to be modified.

But why would the fleeing Israelites avoid the Way of Horus and take such a circuitous route home? The only hypothesis I can form is that they did not wish to encounter the victorious Egyptian army.

Kamose, the last pharaoh of the 17th dynasty, and his younger brother Ahmose I, the founder of the 18th dynasty, waged a long war of independence against the Hyksos rulers. Few details of the campaign are known. It is generally accepted, however, that there was a protracted siege of Avaris, as James Henry Breasted noted in both his History of Egypt (1912) and Ancient Records of Egypt (Volume 2: 1906):

The ... evidence of a soldier in the Egyptian army that expelled the Hyksos shows that a siege of Avaris was necessary to drive them from the country; and further that the pursuit of them was continued into southern Palestine and ultimately into Phoenicia or Coelesyria. (Breasted 1912:215)

8. One besieged the city of Avaris (Ḥt-wᶜr˙t); I showed valor on foot before his majesty; then I was appointed to (the ship) ‘Shining-in-Memphis.’

9. One fought on the water in the canal: Pezedku (Pᵓ-ḏdkw) of Avaris. Then I fought hand to hand, I brought away a hand [Cut off as a trophy, from a slain enemy]. It was reported to the royal herald. One gave to me the gold of valor.

10. Then there was again fighting in this place; I again fought hand to hand there; I brought away a hand. One gave to me the gold of bravery in the second place.

12. One captured Avaris; I took captive there one man and three women, total four heads, his majesty gave them to me for slaves.

13. One besieged Sharuhen (Šᵓ-rᵓ-ḥᵓ-nᵓ) for 6 years, (and) his majesty took it. Then I took captive there two women and one hand. One gave me the gold of bravery, besides giving me the captives for slaves. (Breasted 1906:6-8)

Breasted comments:

... apparently Avaris was captured on the fourth assault; but these brief references to fighting may each one indicate a whole season of the siege, which would then have lasted four years, as that of Sharuhen lasted six ... This throws a new light on the whole Asiatic campaign, for the stubbornness of the besieged and the persistence of Ahmose are almost certainly an indication that the siege is an extension of the campaign against the Hyksos, who, having retreated to Sharuhen, are here making their last stand. We may suppose, therefore, that the siege of Avaris itself also lasted many years, allowing opportunity for a rebellion in Upper Egypt. (Breasted 1906: 7-8)

Sharuhen was in southern Canaan, though its exact location is not known. Tel Heror, 20 km southeast of Gaza City, is a prime candidate.

Significantly, before besieging Avaris, Ahmose first turned his attention to Tjaru, a major fortress on the Way of Horus. On the back of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (a mathematical work commissioned by a Hyksos Pharaoh ), there is an interesting record:

Regnal year 11, second month of shomu, Heliopolis was entered. First month of akhet, day 23, this southern prince broke into Tjaru. Day 25 – it was heard tell that Tjaru had been entered. Regnal year 11, first month of akhet, the birthday of Seth – a roar was emitted by the majesty of this god. The birthday of Isis, the sky poured rain. (Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World: Brown University)

The regnal year is that of the last Hyksos king, Khamudi, while the southern prince is Ahmose I.

With Tjaru in the hands of Ahmose and Avaris besieged, the Israelites may have had no option but to find an alternative route back to Canaan. And if the Exodus took place after the fall of Avaris, the main theatre of the war would have shifted northeast along the Way of Horus, as the Hyksos, pursued by Ahmose, retreated to Sharuhen.

We do know that there was a road running south or southeast from Avaris towards the Wadi Tumilat, where modern archaeologists place Pithom, one of the store-cities of Exodus 1:11 (Hoffmeier 66). Significantly, that is where the second Station of the Exodus, Succoth, is usually placed. But this is a subject we will take up in the next article in the series.

References

- Manfred Bietak & Irene Forstner-Müller, The Topography of New Kingdom Avaris and Per-Ramesses, in M Collier & S Snape (editors), Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen, pp 23-51, Rutherford Press, Bolton (2011)

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), _The Jewish Study Bible , Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Julius Caesar, W A McDevitte (translator), Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic and Civil Wars, Henry G Bohn, London (1851)

- Charles Ginenthal, Egypt and Palestine, Pillars of the Past, Volume 3, Forest Hills, New York (2010)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- Ken Johnson, Ancient Seder Olam: A Christian Translation of the 2000-year-old Scroll, Kindle Edition, Biblefacts.org (2006)

- Kurt A Raaflaub, John T Ramsey, Reconstructing the Chronology of Caesar’s Gallic Wars, Histos, Number 11, pp 1-74, (2017)

- Jonathan P Roth, The Logistics of the Roman Army at War (264 BC–AD 235), Brill, Leiden (1999)

- James Thorne, The Chronology of the Campaign against the Helvetii: A Clue to Caesar's Intentions?, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Band 56, Heft 1, pp 27-36, Franz Steiner Verlag (2007)

Image Credits

- The Exodus (Horace William Petherick): William Horace Petherick (artist), Museum of Croydon, Croydon Art Collection, Public Domain

- Moses Strikes Water from the Rock at Kadesh Barnea: Wikimedia Commons, François Perrier (artist), Public Domain

- Probable Exodus Route According to the Bible (Jewish Study Bible): © 2004 Oxford University Press, Fair Use

- Map of the Wandering in the Desert (Michel van Lochum): Wikimedia Commons, Michel van Lochum (engraver), Public Domain

- Alternative Route of the Exodus: © Knowing-Jesus.com, Fair Use

- The Helvetian Migration: Wikimedia Commons, © Feitscherg, Creative Commons License

- Caesar’s Forced March from Rome to Obulco: Adapted from Wikimedia Commons, © historicair, Creative Commons License

- Avaris, The Hyksos Capital: Adapted from Bietak & Forstner-Müller, The Topography of New Kingdom Avaris and Per-Ramesses, p 22, Figure 25, Fair Use

- The Way of Horus: Adapted from Figure 1: Historical Landscape of the Northeastern Nile Delta, © Bietak & Forstner-Müller, Fair Use

Excellent post buddy

Excellent history. Thanks for share.