Pioneers Of Astronomy: Edmond Halley

PIONEERS OF ASTRONOMY: EDMOND HALLEY

(Image from wikimedia commons)

Edmond Halley was born on 8th November 1656 (29th October by the Julian calendar). His father was also called Edmond and he married Halley’s mother, Anne Robinson, seven weeks before their first child was born. This child was ’the’ Edmond Halley. His younger sister was born in 1658 and named Katherine but she died in infancy. The birth date of his brother, Humphrey is not known, but he died in 1684. Not much is known about Halley’s childhood, but it is known that he had little to worry about when it came to money. His father was an accomplished businessman and landlord. Despite the fact that the great fire of London in 1666 had some impact on his finances, by the time his son was old enough for schooling he made sure Halley had the best education money could buy. At some point before he joined Queen’s College, Oxford in July 1673, Halley had developed an interest in astronomy and his father equipped him with instruments that were as good as any professional astronomer.

THE DIFFICULTY OF LONGITUDE

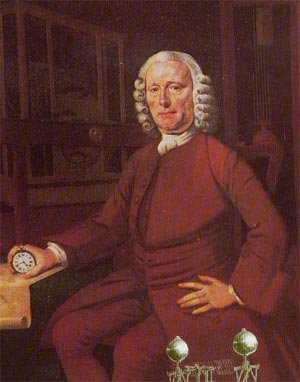

(Image from wikimedia commons)

Halley himself would become a professional astronomer, and he was aided in this pursuit by the fact that Britain was a seafaring nation. In those days, it was very hard to navigate the oceans because of the difficulty in finding longitude. Latitude was not so much of a problem. Any competent sailor could find it by the height of the Sun or by the stars or even the length of the day. But to determine longitude a sailor had to know what time it was aboard his ship and at the same moment know what time it was at home port or another place of known longitude. Nobody, though, had access to timepieces that were accurate enough and it was not unknown for crews to be lost from running a ship into an island, or not being able to find land at all. The nation that discovered a way to find longitude would truly rule the waves and the French announced that they had found a way to do it. They believed they could find longitude by using the Moon as a kind of clock, charting its position against background stars. The astronomer John Flamsteed looked into these claims and refuted them on the basis that stellar and lunar charts were not yet accurate enough.

It was noted, though, that technology now provided a means to track the heavens with greater efficiency. It was the telescope that enabled this. In Tycho’s day, catalogues were compiled using open sights. Essentially, the observer pointed a rod at a chosen star and looked along its length. But now, telescopic sights came with a fine line in their focal plane and this provided a far more reliable way of determining a star’s position. In 1674, in order to produce maps accurate enough to find longitude via the Lunar method, Charles II ordered the construction of an observatory to match the Observatoire de Paris, founded by the French Academy. This directive resulted in the Royal Observatory. It was designed by Christopher Wren, who chose Greenwich hill for its location. The King appointed Flamsteed as its first Astronomer Royal on 4th March 1675 and he took up residence in the observatory on July of the same year.

The race to find longitude was under way. But in the end it was a clockmaker named John Harrison who solved the problem by making marvellously accurate timepieces. However, all that lay in the future and is not all that relevant to our story. What is relevant is that Halley had been mapping the heavens as an amateur in 1675 and found his own observations disagreed with published data. This lead him to the conclusion that his modern equipment enabled him to find the position of stars with a greater accuracy. He wrote to the Astronomer Royal, explaining his findings. Flamsteed had suspected as much, and Halley’s letter confirmed his suspicions. The upshot of this was that the two not only became friends, but Halley also became his assistant, helping the astronomer with several observations.

(John Harrison. Image from wikimedia commons)

MAKING A NAME FOR HIMSELF

Edmond Halley began to make a name for himself in the field, but he was in need of a task that could really help him gain recognition. The main purpose of the observatory was to provide an accurate survey of the northern hemisphere. Halley’s suggestion was that he could do the same thing for the southern hemisphere. His father considered this to be a good idea and he provided his son with a salary of £300 per year and also offered to pay many of the trip’s expenses. Having gained the King’s permission, Halley sailed to the island of St Helena, which was the most southerly land under British control until Cook landed in Botany Bay. Halley returned in 1678 and his catalogue was published in November, an achievement that earned him the accolade ’our southern Tycho’ from Astronomer Royal himself. He was awarded his MA on 3rd December 1678, an event that placed him on equal footing with the likes of Flamsteed.

Halley managed to achieve an awful lot in a short space of time. He published scientific papers on subjects such as planetary orbits, an occultation of Mars by the moon and a large sunspot. During his trip south he not only produced the charts; he also witnessed a transit of Mercury across the Sun and thought of a way to use this as a means to measure the Sun’s distance from Earth, using parallax. At the time, though, his observations were not accurate enough for this proposal to be practical. And after this run of success, it seems Halley became content to consider the work done thus far quite enough, and to just enjoy spending his father’s money. Halley had always enjoyed a good social life and, perhaps inevitably, he was dogged by rumours of sexual misconduct. But what ended his jollities was not the chattering classes, but a comet.

THE COMET

(Image from wikimedia commons)

Comets were perhaps the most mysterious objects to appear in the heavens. Today, it is an exciting event when one appears, because apart from a total eclipse they put to shame everything else. But for the longest time, these beautiful stellar objects were viewed with fear, because they were thought to be portents of doom. Sometimes this paranoia turned out to be justified. A comet appeared in AD 66 over Jerusalem and the city fell to the Romans four years later. In 1066 a comet was seen in England, an event that preceded the country’s defeat at the Battle of Hastings. But, while they might have been heralds of woe, people took comfort in the knowledge that comets only appeared once. Nobody at that time suspected that the comet of AD 66 and 1066 was one and the same.

In November 1680 a faint comet was observed for a few weeks in the early morning sky before it was lost in the glare of the Sun. As comets go it was not a particularly impressive spectacle- in fact the Astronomer Royal missed it entirely. But another comet appeared in December and this one was the most spectacular in living memory. It stretched over the full length of King’s College chapel, its head glowing brighter than Venus. The first comet had appeared when Halley was about to embark on a Grand Tour of Europe and he was travelling in France and Italy when the second one appeared.

Flamsteed, though, was one of the first people to realise that the two comets might actually be the same. He had an idea that maybe the first comet had been attracted to the Sun by a magnetic influence, and then sent away from it. These were just half-formed ideas at the time, so he wrote to Isaac Newton, hoping to start a correspondence. It proved rather difficult in practice, though, since by now Newton had retreated into his shell at Cambridge. Flamsteed tried several times, detailing his explanation that some kind of repulsive magnetic effect had reversed the direction of the comet’s trajectory. Newton finally wrote back in order to point out a flaw in this line of reasoning. Magnetic bodies lose their virtue when they become red-hot, so it hardly seemed likely that the Sun could have a magnetic force. In any case, Newton was not convinced that these were not two separate comets. But if it was one comet, Newton explained that- rather than being repelled from the Sun- the comet had simply gone all the way around it.

FAMILY AFFAIRS

While on his grand tour, Halley was also discussing the comet. He arrived home on 24th January 1682. This grand tour lasted for about a year, which was quite short as these things go. It’s possible that Halley came home early in order to be present at his father’s second wedding. Halley himself was married on April 20th 1682. Not much is known about his private life. His wife was called Mary Tooke; they were married at St James’ chapel, London; she bore him two daughters in 1688 (not twins) called Margaret and Catherine. A son was born in 1698 and named Edmond. After the wedding Halley moved to Islington and carried on with the work of observing the Moon in order to provide the necessary reference data for the lunar method of finding longitude. This was a long-term project for anyone to undertake. It would require observing the Moon for eighteen years as it completed one cycle of its wanderings against the background stars.

Unfortunately, Halley’s work was put on hold when, on the 5th March 1684, his father walked out of his house and was found dead near Rochester five days later. The official verdict was murder, although it could also have been suicide. Apart from the obvious emotional impact, the death of Halley’s father resulted in him having to give up his Fellowship. His father’s finances had been reduced quite considerably by his second wife. When he died, he left no will and Halley found himself in an expensive legal battle over his late father’s estate. Although Halley himself was quite well off and his wife had a decent dowry, the situation was such that Halley had to take up a paid position at the Royal Society, working as a paid clerk. But the rules of the Society stated that paid servants could not be Fellows, which was why he had to give it up.

PROVING A CONJECTURE

A few years before this decision, Halley had entered into discussions with several scientists- discussions that would culminate with him acting as midwife to the most important scientific book yet written. Involved in this discussion was Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke and it involved planetary orbits. Specifically, it involved the idea that Kepler’s laws implied that a centrifugal force tried to push planets away from the Sun and that its strength was inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the star. As they were staying in orbit, this implied that there must be another force, attracting the planets toward the Sun, and that the interplay between these forces resulted in elliptical orbits. At the time, though, this was nothing more than conjecture. Actually proving that an inverse square law must result in planets following elliptical orbits was (mathematically speaking) beyond the capability of both Halley and Wren. Hooke, though, announced that by assuming an inverse square law he could derive all the laws of planetary motion.

The story of Robert Hooke and Edmond Halley’s role in the creation of Newton’s opus, ‘The Principia’, will be our next topic in the Pioneers Of series.

REFERENCES

Science: A History by John Gribbin

“Isaac Newton” by James Gleick

Wikipedia entry on Edmond Halley

To be a pioneer, and especially in Astronomy, is a very noble thing.