Bonkers! The Story Of Zimbabwe and Hyperinflation

BONKERS! THE STORY OF ZIMBABWE AND HYPERINFLATION

(Image from Public Radio International)

Inflation. That's a word that you may have heard from time to time, particularly if you live in Europe and follow news reports of how markets are faring post-Brexit. Inflation can be described as a general increase in the price level, or a reduction in a currency's purchasing power (they both amount to the same thing, really). Many countries-of which the UK is one example-try to meet a yearly target of 2% inflation.

On rare occasions- just thirty times in modern economic history- inflation become hyperinflation, something many economists define as a price level increase of at least 50 percent. One such place to experience hyperinflation as Zimbabwe.

A RICH COUNTRY

Zimbabwe is a rich country. It has huge resources of gold, nickel, iron, platinum and coal. On learning this, some may assume that it also suffered from the so-called 'resource curse'. This refers to the fact that countries possessing an abundance of no renewable and easily monopolised resources also often have crappy governments. This happens because such resources concentrate power into the hands of whoever controls them, and that typically happens to be a governing elite or regional warlord. the ruling elite then have little incentive to build networks of commerce because they can enrich themselves with the monopoly they enjoy on those resources. But they must also defend their monopoly against rivals, again at the expense of providing services for their people. No wonder, then, that Venezuelan politician Juan Alfonzo described oil as "the devil's excrement".

However, prior to the 1990s, Zimbabwe was not at all like a country suffering from a 'resource curse'. In fact, it was a pretty prosperous place. It was a popular tourist destination, and there was a sophisticated industrial sector providing such products as steel, wood, cement and chemicals. There was also a strong banking sector and a property rights system that worked well enough to allow "owners to use the equity on their land to develop and build new businesses" (in the words of C. Richardson). Indeed, after it gained its independence in 1980, the country experienced pretty much sustained growth (with only occasional interruptions), reflected in an average GDP growth rate of 4.3 percent per year.

SIMMERING RESENTMENT

But simmering away underneath all this prosperity was a lot of resentment. In Zimbabwe there were many commercial farms. They provided employment to some 350,000 workers and provided the financial support required for the building and maintainance of hospitals and schools. But they were predominantly owned by white families (about 4,500 such families owned most of the commercial farms), a situation that many viewed as being a consequence of colonialism. People like Robert Mugabe saw these commercial farms as land that had been stolen from black farmers.

So long as it was not acted upon, such rhetoric did not constrain Zimbabwe's growth. But, in the late 1990s, mere words became action. That action, along with other moves made by the ruling party, totally changed Zimbabwe's fortunes.

(Robert Mugabe. Image from wikimedia commons)

THE LAND GRAB

In the 90s, the ruling ZANU-PF party put their plans for wealth redistribution into effect. The result, however, was not quite what the people of Zimbabwe had been promised. This course of action was supposed to free up 'stolen' fertile land and redistribute it among the poorest Zimbabweans. But, instead, the ruling elite got their hands on the most fertile lands. Those farmers were were evicted found themselves unable to repay loans, and their fate sent a signal to foreign investors who fled, taking their assets with them for fear that they, too, would be seized. Foreign direct investment in Zimbabwe fell to zero by 2001, and the World Bank's risk premium on foreign investment rose from 4 percent to 20 percent.

As well as carrying out their threat to take the land owned by white commercial farmers, the ZANU-PF under Robert Mugabe also increased pension payments and other benefits, in a move intended to appease those war veterans who had fought for independence but were increasingly unhappy with the ruling elite's growing wealth. Mugabe also sent the military into the Democratic Republic of Congo because the party wanted to support the regime of Laurent Kabila. More precisely, they wanted to protect their own mining investments. These two events increased government spending, while the appropriation of vast tracts of farmland and the consequences of that had a negative effect on tax revenues. The titles for the appropriated land were not enforced, and that removed a major source of collateral for bank loans and the collapse of land value following the removal of property rights. Lending to farmers dried up, causing investment in farming to plummet.

DIMINISHING REVENUE

Something else that was falling dramatically was tax revenue. The government's budget was under severe pressure, and this was only exacerbated when the government defaulted on the servicing of its loan to the IMF in 2001. This left the Zimbabwean government with a creditworthiness that was effectively ruined, making it impossible to get a loan anywhere else (while, at the same time, the IMF refused such concessions as loan forgiveness, because it wanted to punish the Zimbabwean government for its land reform measures and other policies).

With the consequences of the land reform measures leading to such a reduction in food production that famine was a real threat, and unable to secure a loan with which to buy food from abroad, the government turned to printing money in an attempt to plug the gap between spending and revenue. But this attempt to create money was carried out when the fall in output in the agricultural and manufacturing sector was reducing the amount of goods available to buy. This set things up for inflation that was to spiral out of control. By 2003 the Zimbabwean dollar had suffered such a deterioration in value that it actually cost more to issue those notes and coins than their face value was worth. The government responded by issuing time-limited 'bearer checks' in ultra-high denominations.

HYPERINFLATION

But things continued to deteriorate, and by 2005 more than 80 percent of the Zimbabwean population was unemployed, and the informal sector of the economy (which, in 1980, had accounted for less than 10 percent) became the main source of income. Meanwhile, the government was carrying out measures, but the sole aim of these was to ensure that the ZANU-PF held onto power. The country's resources were appropriated through the confiscation and redistribution of privately-owned assets. And the political opposition (in fact, not just the opposition but the judiciary as a whole) were put under severe intimidation. Human Rights groups reported that roughly 90% of opposition members suffered criminal violation under Mugabe's regime, as well as grim reports of violent attacks and torture on the populace.

By 2007, price rises reached the 50 percent a month level required to be reclassified as hyperinflation, and the deterioration of the Zimbabwean economy was becoming ever-more apparent. Prices were being revised upwards in daily and hourly periods as between 2000 and 2008 output contracted by 40 percent, while the government's budget revenue fell from 28% of GDP in 1998 to less than 5% a decade later.

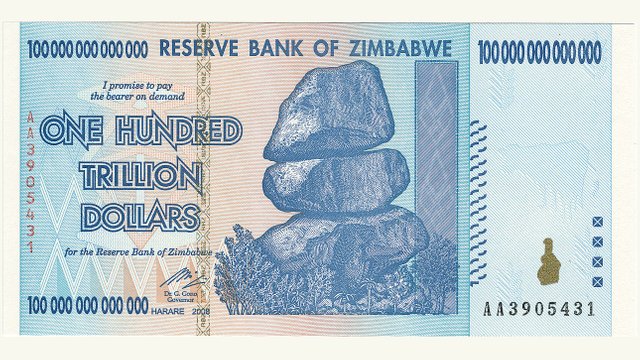

The deterioration of the economy is perhaps most vividly illustrated by the increasingly ludicrous figures printed on the money issued by the Zimbabwean government. In 2006, the Zimbabwean government introduced the 2nd Zimbabwe dollar, at a value of 1000 old Zimbabwe dollars. This was followed two years later by the 3rd Zimbabwe dollar, valued at 10 billion times the 2nd Zimbabwe dollar. It was in 2008 that the hyperinflation reached its peak....at a mind-blowing 79.6 billion percent per month!

A year later, the authorities officially recognised the demise of the Zimbabwean dollar (ordinary people had abandoned it around 2008, in favour of the US dollar which they obtained on the black markets).

THE TRAGEDY

When I see an image of a Zimbabwean dollar valued at one hundred trillion dollars, I cannot help but chuckle. It is just so completely ludicrous. But this was no laughing matter, really, because this Mickey Mouse money symbolises the collapse of what was once a prosperous country. The Mugabe regime's struggle to cling to power led the ZANU-PF to implement policies that destroyed the agricultural sector (which inevitably harmed the rest of the economy, since it's hard to be productive when you are starving). They indulged in expensive military campaigns so as to protect their mining investments, and this (along with their throwing money at disgruntled war veterans) put a severe squeeze on government revenue. All of this lead to a terrifying fall in Zimbabwe's productive capacity. This is not just a story of bad money pushing out good, nor of government mismanagement and corruption. It is a story of a ruined country and wrecked lives. As a 2008 IMF report stated:

"By the end of 2008, most schools and many hospitals had closed, transport and electricity networks were severely compromised, and a water-borne cholera epidemic had claimed more than 4,000 lives".

REFERENCES

RETHINKING MONEY by Andrew Jackson and Ben Dyson

THE BETTER ANGELS OF OUR NATURE by Steven Pinker

thanks for sharing! :-) upvoted

interesting , dont remember hearing of this about of the country on our news channels