(Book) - Tanzimat fails to heal a fallen Empire by Edward Tundidor - Part 3

This 3 part series is my book that uncovers the final years of the Ottoman Empire.

Check out part 1 and 2 @ - https://steemit.com/history/@elumni/book-tanzimat-fails-to-heal-a-fallen-empire-by-edward-tundidor-part-1

https://steemit.com/history/@elumni/book-tanzimat-fails-to-heal-a-fallen-empire-by-edward-tundidor-part-2

In part 2: Chapter 5 & 6

Table of Contents

• Chapter 1: Implementing the Tanzimat reforms

• Chapter 2: The economic and social construct of the empire

• Chapter 3: Western Education and Civil Rights in the Ottoman Empire

• Chapter 4: The decay of the empires power due to nationalism

• Chapter 5: Nationalism sparks revolution

• Chapter 6: The World War 1 genocide of the Armenian subjects

Chapter 5 - : Nationalism sparks revolution

Armenians in the late 1880s and 1890s felt that the greatest suppression of their civil liberties and political involvement occurred when no one in the community spoke up and fought against their Muslim oppressors. With new nationalistic Western education and revolutionary ideals built into the Armenian subjects, a revolt started to build in Anatolia within the Russian Caucasus.

The Armenian political group called Defenders of the Fatherland, who ended up serving long prison terms for their uprising in 1883. Armenians based in the Russian caucuses embraced the idea of national liberation and felt it was their only way to vanquish the oppressive Ottoman political and social systems. Many individuals in the Armenian revolutionary groups called upon peasants and business owners that had a significant stake in the local economy to take up the cause a revolution, but these groups did not want to get involved for fear of incarceration and torture or the financial damage it could cause. Revolutionaries went as far as to “attack Turkish army units”, they brutally killed Muslim villagers and attempted to assassinate the governor of Van in November 1892. Armenian revolutionaries pushed for the refusal of paying the customary dues to Kurdish chiefs, which led to intense fighting between the two groups which concluded in a “promise to arm amnesty” to the Armenians if they surrender. The decision to surrender became costly on the part of Armenians as villagers were indiscriminately massacred by their Mahommedan neighbors. European protector Nation’s called for extensive reform measures upon the Ottoman government for their lack of protection to its Armenian subjects. Scholars have recognized the surrender on the part of Armenian revolutionaries as a ploy to “draw the attention of the Christian world and bring about the European intervention” , but this perceived underhanded tactic on the part of the Armenian revolutionaries has not been proven as fact. The tension was built to a climax in Anatolia between the Turks and the Armenians in the summer of 1894 leaving over 256 Armenians killed in their open revolt against the enforced tax that doubled at the time. The violent tension continued with the Sultan refusing to adhere to reform provisions sanctioned by European countries in the mid-1880s Berlin conference; is considered as an open act of defiance on the part of the Ottoman Turks. The mindset on the part of the Ottoman Turks to use violence against the Armenian revolution was a reaction of jihad, which is a provocation that's recognized as a threat to the Empire. Islam states that any threats to the Ottoman Empire must be answered by, a “call for marshaling all-out effort in the face of great challenges” caused by forces that threaten the Empire and Islamic ideology.

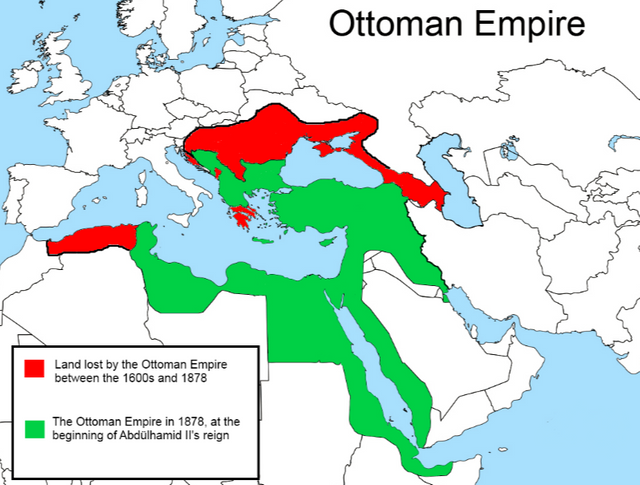

The tension between Christians and the Ottoman Turks persisted over a dispute of ideological principles within the Empire’s political framework, along with disputes over territorial boundaries set the stage for relations completely unraveling as the Ottoman Empire was entering the 20th century.

After the constitutional revolution of 1908, the Young Turks reasserted themselves with the emergence of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) to vanquish the rule of Sultan Abdul-Hamid. Unlike other political groups in the Ottoman Empire, the Young Turks were well organized and enjoyed the advantage of gaining power through an armed revolt, and the opportunity to work alongside the Sultan in developing a Western education system and improving the infrastructure of the Empire. The Young Turks were outwardly rejecting old traditional Ottoman values of government and society and were trying to formulate the adaptation of “Turkish language education in schools” , to change the culture and ideological values of the Ottoman populace to suit CUP initiatives moving forward. In July 1909, the CUP made it a requirement of Muslims and non-Muslims to serve in the military to spread the “Turkification” to its wide variety of ethnic groups, and to get its populace on common ground of adopting a shared national identity. Despite this common identity, the Young Turks strived to maintain control of economic growth and development for Muslims primarily maintaining a sense of property and saddling the economic burden upon its minority subjects. The social, ethnic divide between the Muslim and non-Muslim subjects was significantly greater in the years leading up to World War I due to minorities following the “Jewish model” while others continue to advocate for independence with the help of the European protector nations.

Chapter 6 - The World War 1 genocide of the Armenian subjects

The Young Turks were well aware of minorities disdain for their brand of political policy, and began in the years leading up to World War I developing a strategy to extinguish undesirable nationalities in this nation as a defense mechanism to maintain the Young Turks political dominance over the Empire’s territory. It is speculated that the Saloniki Congress developed the agenda to eradicate the Armenian subjects, and it happened to be discussed in several secret meetings involving high-ranking CUP officials.

Being steered by the teachings of whom many called “the philosopher of the Ataturk revolution” Ziya Gokalp, who called for the preservation of Turkish nationalism that is based strictly on Turkish “social solidarity.” The principles of this secret plan to eradicate the Armenian people is comprised in December of 1914 into January of 1915, which unfolded in 10 Commandments of progress and organization of the Armenian genocide. This comprehensive plan talked about the confiscation of firearms, the use of disciplinarian military forces, the eradication of all males and high ranking members of religious or political groups only leaving women under the age of 50 alive. The plan went to call for the total elimination of all Armenian men in the military, also cut off Armenian communication to protective European nations, and this coordinated plan was to have been simultaneous, with limited personnel aware of the initiative. Many have speculated that this coordinated purge by the Young Turks is not documented as fact leaving little-written evidence supporting this argument. Despite the alleged plan for the Armenian genocide, the CUP ruled by the Young Turks “used the cover of war to fulfill its long-term ideological goals” that have been brewing since the inception of the group in the mid-to-late 19th century.

When the CUP implemented conscription to its non-Muslim subjects, it was met with a harsh reaction from Armenians who “showed little enthusiasm to serve in the Army” and would rather pay the tax than shed blood for a nation that they do not have a common political identity. Despite the lack of enthusiasm for military service, Armenians did join the Army with many of them being illiterate, with minimal chance of becoming promoted to high-ranking corporal or sergeant positions.

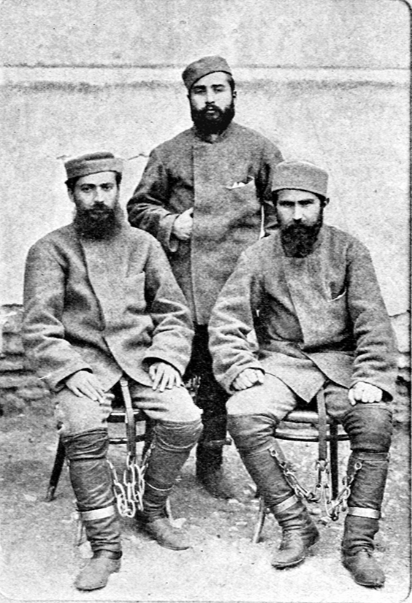

Armenian soldiers

Many senior officers were disgusted by their Armenian soldiers for their lack of intelligence and identification to Islamic ideals even though their conscription card stated their religious faith was Islamic. The lack of intelligence on the part of minority soldiers infuriated the senior officers as they had to re-educate the Armenian soldiers to make them competent military fighters of the Ottoman Empire. Many military officers blamed the divide of education between Muslim and non-Muslim soldiers was “a chasm has been formed between the upper stratum of society and the common people (halk), which has been deepening for centuries” . The inclusion of Western education which opened nationalistic ideals helped broaden the social divide between Muslims and non-Muslims because of their lack of communal cohesion within the Empire. High-ranking Muslim officers also complained about the lack of human sentiment on the part of Armenian soldiers and questioned if they would put themselves in harm’s way to help their Muslim counterparts. High-ranking officers answer the call of educating Armenian soldiers because they “simply wanted to indoctrinate the uneducated men with their ideas and beliefs” so they can become adequate soldiers built on Islamic ideals. The initiative of using religious ideas to administrate military and political affairs was a “revival of religious fervor” under the umbrella of Turkish policymaking initiatives. Once World War I was initiated the Ottoman Empire joined the alliance of Germany and Austria but didn’t need the authorization of Germany to realize the “advantages of issuing a jihad declaration” as the Empire entered a total war.

The Young Turks were well aware of the inadequacy of the Armenian soldier. During World War I the Armenians served only one purpose where they were not a liability, and that was to work in the Ottoman battalion ranks. The Ottoman military force collectively was a brutal experience for all soldiers, but the experience felt by the Armenians in the battalions was a far more decimating experience for the individual soldier. The construct of the Armenian Battalion served a dual purpose for tactically giving the most strenuous work to the non-desirable subjects while still adhering to the 10 Commandments program of the Armenian genocide. The men that comprise the Armenian Battalion were between the ages of 20 and 45 using the most able-bodied individuals of the Armenian populace, to eradicate the ethnicities physically fit and able men, in an attempt of ethnic cleansing. The deplorable conditions are illustrated in eyewitness accounts as they “describe atrocious conditions in the labor battalions: the soldiers were underfed, exhausted, suffering from disease.” Armenian Battalion soldiers had the displeasure of hauling large amounts of equipment because the Empire lacked a proper railroad system for import or export and lacked the use of beasts of burden to transport military supplies and equipment. With the Ottoman Empire entrenched in total war, the Young Turks were seizing the opportunity of “fully exploiting their available resources” , particularly using the Armenian subjects as a resource. The Ottomans also used the available resources available to them from age-old capitulations which hampered their economic capabilities. The treatment of the Armenian battalions is considered the most dehumanizing conditions of any of the Ottoman soldiers during World War I.

The demise of civilian minorities commenced as the Ottoman government decided to transport Armenians out of their native homeland in a forced migration as a means to homogenize the Empire in a form of ethnic cleansing. The Ottoman government went as far as the Balkans to the Arabian sectors of the Empire to remove Christian and Jewish subjects from the “Ottoman body politic” giving them the designation of being unlawful combatants to the safety of the state. The government made this determination because of past uprisings and political revolutions; this was also the perfect opportunity for the Ottomans to avoid intervention from European protector nation’s because they would be hard-pressed to get involved during a total war situation.

The Ottoman Empire was also hard-pressed to keep its army fed as troops in Syria were rationed to “approximately 3 ounces” of grain per day, causing anarchy amongst his troops against its superior officers. One of the contributing factors for a lack of grain rationing grain producers created artificial scarcity during the war as “flour prices had begun to climb ominously” , which left civilians little flexibility to purchase grains. The Young Turk regime did not safeguard the rampant famine in Syria as “local agricultural work or replacement of animals” were not properly provisions before the war effort to protect the welfare of all ethnic groups in the region. The disdain for the Ottoman empires use of resources and funding for the war effort persisted among its Arab soldiers when the Empire “spent money on celebrations at the expense of its obligations” of feeding its civilian population and troops. Ottoman soldiers were not pleased with celebrating small victories in the war while there was real pain and suffering unfolding amongst its people and military.

The initiative of starving out the Armenians was a part of the plan to homogenize the Ottoman Empire, as the government removed the Armenian civilian population from their ancestral homelands. Armenian women and children were subjugated to finding the most meager of substance, as many were witnessed eating grass and weeds to survive.

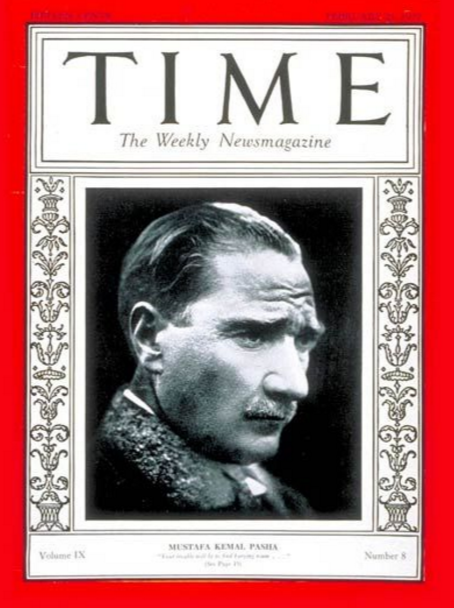

Mustafa Kemal Pasha made the authorization banning the Armenians return to their ancestral homelands leaving many women and children in particular starving to the point that they look like mm mere skin and bones, as seen in images from articles dispelling Armenians loss of property during their forced migration.

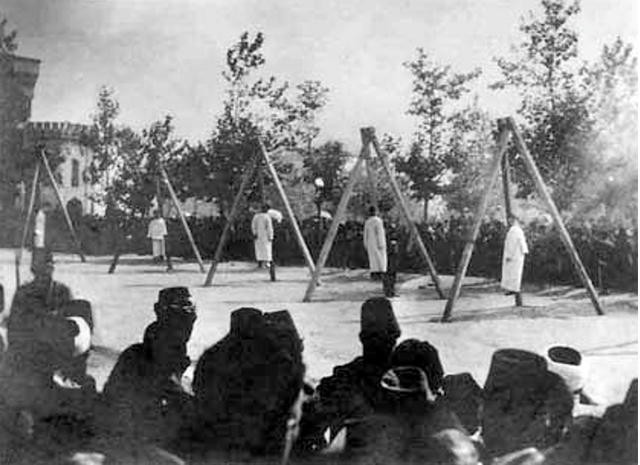

The tragic horror inflicted upon the Armenians extended to Constantinople with a picture showing the execution of five Armenian men in June 1915. The brutality of this execution was a public display to show the outward disdain for the Armenian people, and how they no longer have a place within the Ottoman Empire. Other brutal acts of execution occurred with the beheading of Armenians as seen in images.

The Young Turks displayed that they had no moral compass as they administered their brutality against Armenians. The visual evidence of the ethnic cleansing within the Ottoman Empire is evident in an image displaying a pile of skull and bones of Armenian subjects who were burnt alive, under the watch of Ottoman soldiers. The Young Turks stood fast to their commitment to homogenize the Ottoman Empire as they deported as many as 1 million Armenian civilians during World War I. Images reflect the pain and despair as caravans transported hordes of refugees via horseback from their ancestral villages into the barren wasteland of the middle eastern desert regions, never to return to their home. Images of the Armenian cultural Center of Karabakh display the total vanquish of the Armenian civilian population, as the visual illustration of their former homeland shows nothing but desolate destruction at the hands of the Young Turks. The genocidal mission fueled by newly formed nationalistic ideals based on Islamic Turkish culture helped fuel the call for jihad on the Armenian people as the Ottoman empires primary measure during total war to preserve the Empire.

The Tanzimat reforms did not hold up to the obligation of repairing the centuries old fragmentation between Muslims and non-Muslim subjects. Ethnic segmentation was a part of the political and social fabric of the Ottoman Empire throughout the 18th century, particularly during the Tanzimat reform years. Little was done on the part of the Ottoman government to include its minority subjects in the political process which led to political revolutions and revolt. Instead of resolving these issues with the obligations of the Tanzimat reforms, rather the Ottoman government continued its pragmatic approach towards solving the problem of social inequality among its non-Muslim subjects. Ethnic and religious relations continue to falter due to the inclusion of Western-style education which broadened the nationalistic horizons of both Muslims and minorities throughout the Empire. This newfound nationalistic pride spawned the Young Turk movement which built their ideology on homogenizing the Empire and ridding it of undesirable segments of the population who jeopardized the preservation of the Empire. Western education helped Christian Armenians build nationalistic ideals after the promises of Tanzimat reform were not met. The tension between ethnic groups culminated in the wake of total war as the Young Turk’s in the CUP conceptualized a plan to eradicate the Armenian problem from the Empire in a quest to purify the Empire from undesirable subjects who do not adhere to Islamic ideals. The Young Turks seized their opportunity in World War I under the guise of total war issue declaring jihad against those whom they deem enemies of the state, to preserve the Islamic Turkish state, which was modified by Western nationalistic ideals.

Bibliography

Aksakal, Mustafa. "‘Holy War Made in Germany’? Ottoman Origins of the 1914 Jihad." War in History 18, no. 2 (2011): 184-199.

Al-Qattan, Najwa. "Litigants and neighbors: The communal topography of Ottoman Damascus." Comparative studies in society and history 44, no. 03 (2002): 511-533.

Eissenstat, Howard Lee. “The Limits of Imagination: Debating the Nation and Constructing the State in Early Turkish Nationalism.” ProQuest, 2007.

Fawaz, Leila Tarazi. A Land of Aching Hearts: The Middle East in the Great War. Harvard University Press, 2014.

Göçek, Fatma Müge. "Ethnic segmentation, western education, and political outcomes: nineteenth-century Ottoman society." Poetics Today (1993): 507-538.

Guenter, L. E. W. Y. "The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey." A Disputed Genocide, The (2005).

Jacobson, Abigail. "Negotiating Ottomanism in Times of War: Jerusalem during World War I through the eyes of a local Muslim resident." International Journal of Middle East Studies 40, no. 01 (2008): 69-88.

Rodogno, Davide. "Exclusion of the Ottoman Empire from the Family of Nations, and Legal Doctrines of Humanitarian Intervention." Against Massacre. N.p.: Princeton UP, 2012. 36-61. Print.

"The First Intervention in Crete (1866-69)." Against Massacre. N.p.: Princeton UP, n.d. 118-23. Print.

Parakhodov. Armenians Burnt Alive in Sheykhalan by Turkish Soldiers. Digital image. Genocide Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2016.

Parakhodov. Beheaded Armenians. Digital image. Genocide Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2016.

Parakhodov. Execution of Armenians in the Constantinople. Digital image. Genocide Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2016.

Parakhodov.Kemal Ataturk and Depriving Armenians of Property. Digital image. ARMENIAN GENOCIDE CENTENNIAL. N.p., 29 Dec. 2015. Web.

Parakhodov. The Panoramic View of Shushi - Armenian Cultural Center of Karabakh, after the 1920 Massacre and Destruction. Digital image. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2016

Parakhodov. The Transportation of Refugees. Digital image. Genocide Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2016.

Schilcher, Linda Schatkowski. "The Famine of 1915-1918 in Greater Syria."Problems of the Modern Middle East in Historical Perspective: Essays in Honor of Albert Hourani (1992): 229-58.

Schull, Kent F. et al., eds.. “Criminal Codes, Crime, and the Transformation of Punishment in the Late Ottoman Empire”. Law and Legality in the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey. Ed. Kent F. Schull et al.. Indiana University Press, 2016. 156–178. Web

Yanikdağ, Yücel. 2004. “Educating the Peasants: The Ottoman Army and Enlisted Men in Uniform”. Middle Eastern Studies 40 (6). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 92–108.

Zurcher, Erik Jab. "Ottoman Labour Battalions World War I." (n.d.): n. pag. 1-5 print.

Zürcher, Erik-Jan. "The Ottoman Empire 1850-1922-Unavoidable Failure?."Social History 43, no. 3 (2002):

Tanzimat fails to heal a fallen Empire: Is available now on Amazon.com for $0.99 use this link for your purchase. ( Kindle format Only) http://amzn.to/2fVWZkS

If you enjoyed my work

All proceeds from upvotes on this post are going to more Steem Power.