The field of the Mesoamerican Ball: Copan. Part II

The field of the Mesoamerican Ball: Copan. Part II

Source

The field of the Mesoamerican Ball, Tlatchtli or Ullamaliztli

The pragmatic function, use, of the building would have responded to very specific issues: a mystical or religious character and a profane one that sometimes fused the ludic and the political. In this way, the shape and location of the ball field of Copán is in correspondence with the Mayan worldview: located in the lower sectors of the ceremonial center, this would be symbolically and proportionately closer to the Underworld, if we contrast with the pyramids.

In the pre-Hispanic city of Mesoamerica, there are multiple architectural elements that make them participants in a set of cultures from the same root. Among the elements present, in the generality of the archaeological cities, are the pyramid, the square and the ball game. The pyramid, for its part, points to the sky and is located at the top of the cities; the square, after the pyramid, establishes the relationship between the people and the upper world and, in turn, the ball game, is located in the lower sectors, to enter into relation with the underworld. In this way, the square is presented as an articulating element between both worlds. (Ocampo Hurtado, p.18).

However, the field is more than a structure that represents the eternal battle between life and death, other interests such as the lack of fertility of crops and even the survival of life would be at stake.

For Ocampo Hurtado, ball fields built by the ancient Mayans would have some common characteristics

The court, normally constituted by two parallel and inclined structures, paramentan a central and longitudinal horizontal space, which ends its ends by transversal spaces, to give the form of double T, which characterizes it. Although the courts of the ball game have variations to their form (Martínez, 2008) there are elements that identify them as the same architectural unit, destined for sacred or sporting activity. (Ocampo Hurtado, p.19).

For its construction this same author refers that:

The surfaces of the court, like the generality of Mesoamerican prehispanic architecture, were built in rock, later covered with lime and painted with minerals of bright colors. On the floor, a black or green stripe divided the tlachco into two sectors; in each of these sectors and in the walls that delimit the space, were located the rings, called tlachtemalácatl, which were used as a target for the rubber ball. (Ocampo Hurtado, p.20).

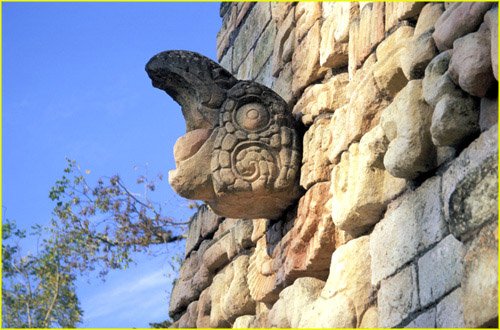

The rings will have variants according to the region where the ball field is located, in some places it will be round, as shown in figure A, and would symbolize the cyclical aspect of life and seasons. In others it will have the shape of a macaw, as in the case of Copán, figure B, a bird that represented ambivalence. In a passage of the Popol Vuh, Hun-Hunanpú's arm is torn off, in the field of the ball this bird symbolizes the movement of the Sun.

Figura A

Figura B

Copán was abandoned by the Maya around the 10th century AD. C. and its excavations began in the 19th century. Many structures, including the ball field, were exposed to the rigors of use and abandonment. In themselves the existence and persistence of a large part of the structures constitute, after so many centuries, an irrefutable proof of the resistance and the appropriate use of the materials.

While many of the artistic friezes that adorned the buildings did not tolerate the passage of time and constant exposure to natural agents, or ignorance, pillage and the lack of adequate policies for conservation, preservation and restoration; the ball field demonstrates great ingenuity and the use of limestone to generate a structure that has resisted all those agents mentioned above.

On the other hand, the uniqueness and beauty of the Ball Field that concerns us are widely studied aspects. On this subject there have been several researchers who have mentioned the magnificence of this monument

According to Cheek (1983: 15), the Main Group plaza is a wide flat surface entirely lined with structures, within which the Ball Game Court, some isolated structures and the large stelae were erected. The size, complexity and luxury of the architecture deployed throughout the area clearly indicate that the Main Group was the religious and political center of the Copán Valley and the surrounding regions during the Classic Period (Pineda, Véliz and Agurcia, p 16).

The harmony and the use of natural resources that is evident today, is also seen in the reproductions made from the studies practiced throughout the city of Copán. (Figure C)

Source

This built space has a symbolic value within the Mayan cultural context. In Mesoamerica we have found about 1500 courts, this gives us an idea of the importance of this game in a mandatory ritual.

The game symbolized in turn the passage from life to death. It is autotelic in itself. It represents the worldview of your world, a belief system, which is reflected or is clearly described in the Book of Council or Popol Vuh, in which the word takes part of a symbolic, ritual and mythical character in which this game represents this culture.

Bibliographic references

Alvarado Tezozómoc, Fernando (s / f). Crónica Mexicáyotl. National Autonomous University of Mexico. Retrieved from: http://www.tlamachtia.mexicayotl.mx/panel/documentos/cargas/CRONICA.pdf

Anonymous. Popol Vuh in Maya Literature (s / f). Ayacucho Library: Caracas. Retrieved from: http://www.bibliotecayacucho.gob.ve/fba/index.php?id=97&backPID=103&begin_at=48&tt_products=57

Cabezas Carcache, Horacio (2012). Copán, Athens of the new world. In Horacio Cabezas Carcache (Ed.) Mesoamerican Cities. Mesoamerican Publications: Guatemala. Retrieved from: http://www.umes.edu.gt/libros/CIUDADESMESOAMERICANAS.pdf

Canute A. Marcello, Ellen E. Bell and Cassandra R. Bill (2007). From the limit of the kingdom of Copan: Modeling the socio-political integration of the Classic Maya. In XX Archaeological Research Symposium in Guatemala, 2006 (edited by J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo and H. Mejía), pp. 904-920. National Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, Guatemala. Retrieved from: http://www.asociaciontikal.com/pdf/53_-_Canuto,_Bell_y_Bill.pdf

Guatemalan youth launch videogame (May 29, 2013). Government of Guatemala, Ministry of Culture and Sports. Recovered from:

http://mcd.gob.gt/jovenes-guatemaltecos-lanzan-videojuego/

Morales Hidalgo, Yesmín. (2013, October 25). Historical evolution of the definition of Built Heritage Message on Blog. Retrieved from: http://patrimonioedificado2013.blogspot.com/2013_10_25_archive.html

Ramírez Torrealba, Elvis and Rosa López (2005). A look at the Mayan ball game as a magical religious myth. In Efdeportes Revista Digital, Buenos Aires, Year 10, No. 85, June 2005. Retrieved from: http://www.efdeportes.com/efd85/maya.htm

Ocampo Hurtado, Juan (2012). The pre-Hispanic ball game and the Olympic Games. Magazine U.D.C.A. Act. & Div. Cient. 15 (Olympian Supply): 17-25, 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.udca.edu.co/attachments/article/1736/juego-pelota-prehispanico-juegos-olimpicos.pdf

Viel, René and Jay Hall (2002). The natural and cultural landscape of the Copan Valley. In XV Archaeological Research Symposium in Guatemala, 2001 (edited by J.P. Laporte, H. Escobedo and B. Arroyo), pp.872-877. National Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, Guatemala. Retrieved from http://www.asociaciontikal.com/pdf/78.01%20-%20Viel%20-%20en%20PDF.pdf

UNESCO (2013). The Criteria for Selection. Retrieved from: http://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/ Consultation: 2013, October 25

María Cristina Pineda de Carías, Vito Véliz and Ricardo Agurcia Fasquelle, in Yaskin Volume XXI, p. 16

#topfive #steemfamilyhi

apoyando el #TopFive

Apoyando con @piscis

Buen amigo @aresbon!

Saludos y mi apoyo desde el #Top5 de #steemfamilyhi

Saludos @aresbon, mi apoyo desde el #Top5 de #steemfamilyhi