History of Medicine: Prehistoric Medicine

I have decided to start a series of posts dedicated to two of my greatest passions: medicine and history, because as they said there: "there is no science without history". The history of medicine is a branch of history that is dedicated to studying medical knowledge and practices over time.

Many will ask why I consider the history of medicine important, the obvious answer is because I am a doctor, however, I consider that the history of medicine has a very close relationship with the history of civilization and has influenced it on many occasions, medicine is not only a biological science, it is also a social science and also, knowing about the history of medicine is also knowing about the history of man's eternal struggle against disease and if there is something that has been invariable in medicine is that doctors have always been there to care for, improve and try to heal, serving tirelessly to our patients, being curious, enterprising. We have never abandoned the search for new forms of help, since the dawn of humanity we have a commitment to our profession and to our patients, and that is a story that I would like everyone to know. I would also like to introduce those pioneers, visionaries for their time, who have been and will be a source of inspiration and who have made enormous contributions to the progress of medicine. Many reject the past with their old theories and beliefs and go wild for new discoveries, however, from my perspective, history will always be important and I return to one of the first sentences of this post "there is no science without history".

After this introduction we will start the topic of today's post: "Prehistoric Medicine", so called precisely because there are no written records of it. We can say that since prehistoric times there is a need to alleviate suffering, since diseases and pain were born with life itself.

The prehistoric man reacted instinctively (like the animals that lick their wounds and get fleas out themselves). The spines were extracted from the skin; used friction for abdominal or muscular pains, sucked their wounds and contained hemorrhages by compression. No one can say with certainty what the prehistoric peoples knew about the functioning of the human body.

As there are no written records of that time, the data are obtained mainly from ethnology and paleopathology.

Ethnology is the study of civilizations and there is the possibility of establishing certain similarities between the medical practices of certain ethnic groups (particularly primitive peoples of West Africa) with those of the man of prehistory.

In terms of paleopathology (a term defined by Marc Armand Ruffer (1859-1917), a British doctor and archaeologist), this science is based on the analysis of fossil bones in order to know the diseases that man suffered in the prehistory, as well as the traces that the medical activity may have left in them. This is how congenital anomalies have been identified such as achondroplasia, endocrinological diseases (gigantism, acromegaly, gout), degenerative diseases (spondylosis, osteoarthritis, as a consequence most likely of lifting heavy objects on a frequent basis), tumors such as osteosarcomas and bone metastases.

Studying the first Homos is rare to see that they exceed 50 years (most of the skeletons are of people of about 15 years), so there is practically no evidence of degenerative diseases or associated with aging. However, the findings related to traumas, typical of an outdoor life, are very common.

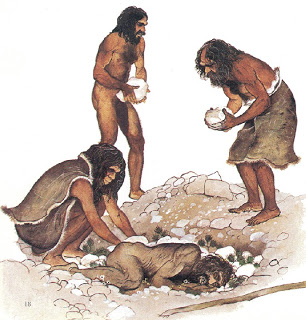

Of particular interest are trepanations (removal of a segment of bone from the skull). Almost always performed in the form of a disc and allowed to reach the interior of the cranial cavity. It’s most common indications were cranial trauma (to relieve the pressure of internal bleeding) and the removal of brain tumors. It was also used as a treatment for headaches, hydrocephalus, hysteria, delirium and epilepsy. There is a hypothesis that it could be used to obtain a fragment of the skull that would serve as a remedy or that it served as a "way to escape" from the disease (or for the "evil spirit") of the body.

To make it, knives, saws, hammers and drills were used. They had to be done with a lot of delicacy and precision, so they are difficult to imagine for that time, without anesthesia and without proper instruments. The holes were not covered again (what is done today) and it is presumed that the pieces of bone were used as amulets.

They were most commonly practiced in the parietal or occipital bone and oval shaped, measuring generally 3 to 5 cm. The skulls with older trepanations come from the Mesolithic period and date from about 8,020 to 7,620 years ago.

In many skulls with trepanations there is evidence of bone regeneration, which indicates that the patient survived the procedure. In addition, in the majority of cases there were no signs of infection, so it is intuited that there were methods to prevent them. In some caves there are paintings in which fingers are missing from hands. They could be amputations performed as treatment of infections or spontaneous from gangrene or extreme cold.

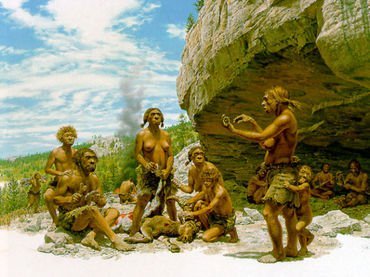

Relationship of ancient medicine with religion and magic

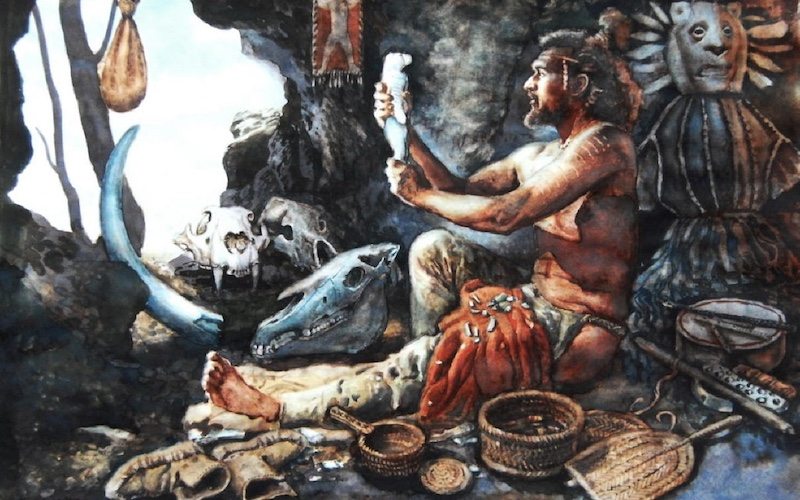

The relationship between medicine, religion and magic is very close, not even modern medicine has been able to completely separate itself from this relationship. The figure of the shaman, medicine man, witch-doctor or healer appears in the Mesolithic, as an intermediary to go before the gods and to expel the evil spirits. He is considered the first doctor in the history of mankind. In addition, he directed the rites of puberty, fertility and death as well as the rites with which people tried to overcome collective crises such as epidemics, storms or hunger.

A clear example of the relationship between medicine and magic is the administration by the shaman or healer of quinine to a person with malaria. We could judge this act as medical (quinine kills the disease producing agent) but it is also accompanied by an exorcism-type ritual, to expel the "bad spirits" and we can’t deny the "psychosomatic" effect that this ritual has. In Palaeolithic excavations, necklaces with animal teeth have been found, similar to many carried by children of tribes today to "prevent complications" of the dentition. Meteorites were given magical properties (if attached to the kidneys it was an effective remedy against kidney stones, for example). The cures were practiced by the shaman, healer or sorcerer, who fulfilled the functions of doctor, pharmacist and priest.

Man attributed natural phenomena to all-powerful wills and paid reverence to the sun, the moon, fire, volcanoes, etc. He attributed the disease directly to those wills (punishment of the gods) or to evil spirits and in this way this magic-religious concept of the disease lasted for millennia. Equally the diseases could be the result of a "spell" thrown at the victim by an enemy.

On the other hand, prehistoric man also learned to use certain compounds "in a magical way" to remove fever, heal wounds and although its implementation was successful, the interpretation of the disease remained magical. They used drugs such as the sacred shell, cocaine, curare, ephedrine, reserpine, among others. Probably this process of "trial and error method" led to the discovery of which compounds had some medicinal value and which were poisonous. Mauve (for colon cleansing) and yarrow (used to reduce bleeding) were used about 60,000 years ago. Certain fungi were also used as laxatives.

To finish I can only say that although the knowledge of prehistory has come to us through fossils, paleontology, paleopathology, sculptures, studies of primitive peoples and cave paintings, the answers to many of our questions are still simple conjectures.

I hope you liked it, see you in the next post.

References:

1)http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/historia-de-la-medicina/

2)https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/info/medicine/prehistoric-medicine.php

3)https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-medicine

4)http://www.healthguidance.org/entry/6303/1/Prehistoric-Medicine.html

5)https://historiaybiografias.com/historia_medicina/

6)https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historia_de_la_medicina

7)https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medicina_en_la_prehistoria_y_la_protohistoria

8)http://www.monografias.com/trabajos63/historia-medicina/historia-medicina.shtml

Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by eleyda78 from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, theprophet0, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows. Please find us at the Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.

If you would like to delegate to the Minnow Support Project you can do so by clicking on the following links: 50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP.

Be sure to leave at least 50SP undelegated on your account.