Different types of tectonic faults on earth

In geology, a fault is a fracture, usually flat, in the terrain along which the two blocks have slid relative to each other.

The faults are produced by tectonic forces, including gravity and horizontal thrusts, acting on the crust. The rupture zone has a broadly defined surface called the fault plane, although it can be called a failure band when the fracture and the associated deformation have a certain width.

When the faults reach a depth in which the fragile deformation domain is exceeded, they become shear bands, their equivalent in the ductile domain. Faulting (or faulting) is one of the important geological processes during the formation of mountains. Also, the edges of the tectonic plates are formed by faults up to thousands of kilometers in length.

Elements of a fault

Fault plane:

Plane or surface along which the blocks that separate in the fault move. This plane can have any orientation (vertical, horizontal, or inclined). The orientation is described according to the heading (angle between the North heading and the line of intersection of the fault plane with a horizontal plane) and the dip or manteo (angle between the horizontal plane and the line of intersection of the fault plane with the vertical plane perpendicular to the course of the fault). In general, the fault planes are usually curved. The fault plane can be polished by friction, giving rise to so-called "fault mirrors" . It is called a 'failure band' when the deformation zone has a certain width. Instead of a fault band, it is also used fault zone (translation of the English fault zone) which produces confusion because fault zone (s) is also used as a synonym of fault system.

Blocks or fault lips:

These are the two rock portions separated by the fault plane. When the plane of failure is inclined, the block that is above the plane of failure is called 'block hanging' or 'lifted' and the one below, 'block yaciente' or 'sunken'.

Jump or displacement:

It is the net distance and direction in which one block has moved relative to the other.

Fault Stretch Marks:

These are rectilinear irregularities that may appear in some fault planes. They indicate the direction of movement of the fault.

Fault hook:

In some cases there is a drag fold on one or both lips of the fault, whose orientation will be different depending on whether the fault is normal or inverse and will indicate the direction of relative displacement.

Geometric classification of faults

From the point of view of the relative displacement of the blocks involved, the faults are classified as follows:

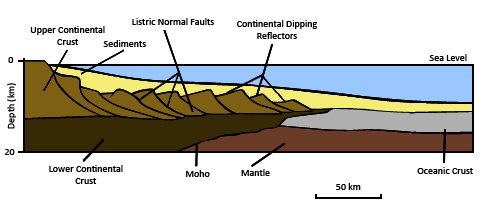

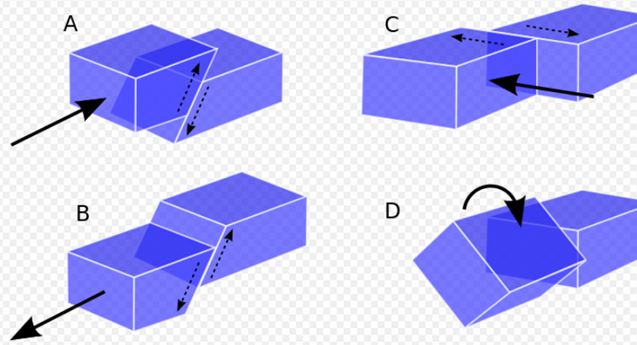

Normal, direct or gravity failure: when the hanging or roof block moves downwards with respect to the adjacent or wall block. The fault plane is tilted.

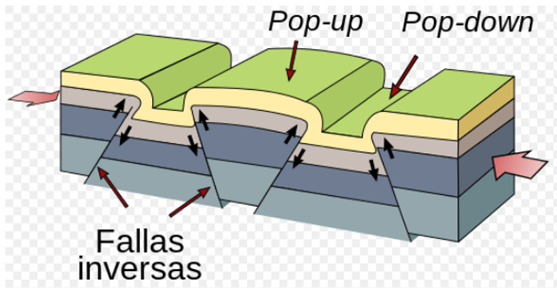

Reverse fault, when the hanging block moves upwards with respect to the patient. They are denominated thrusts to the reverse faults of low angle of dip. The fault plane is tilted.

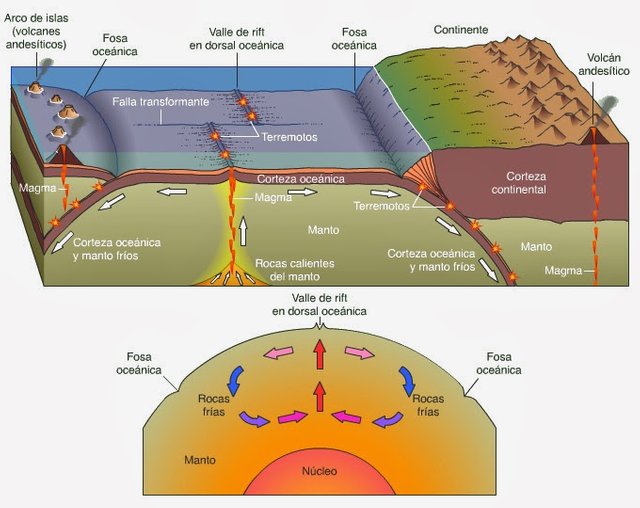

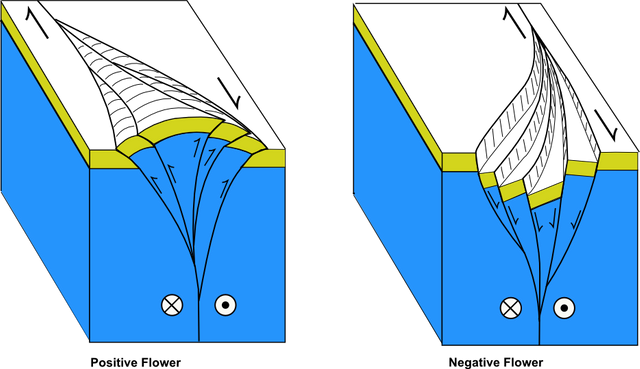

Course failure, in direction, directional, running or tearing: when the displacement is horizontal and parallel to the course of the fault. They can be, according to the direction of movement of the blocks (referenced to the position of an observer located on one of the blocks), sinistral or left directional, when the block opposite the one occupied by the observer moves to the left, and dextral or Directional right, when the block moves to the right. The fault plane can be inclined or vertical. A particular type of faults in direction are the transforming faults, which displace segments of constructive edges of plates and the fault plane is usually vertical.

Oblique or mixed fault: when the displacement is oblique to both the heading and the direction of dip. They are described simply as a combination of the terminology of the previous ones, resulting in four possible cases: sinistral inverse, sinistral normal, dextral inverse and dextral normal.

Rotational failure: when there has been a rotation component in the relative displacement between the two blocks separated by the fault. In turn they can be divided into:

Scissor failure, when the axis of rotation is perpendicular to the plane of failure.

Cylindrical failure, when the axis of rotation is parallel to the fault plane. The fault plane is usually curved.

Conical failure, when the axis of rotation is oblique to the fault plane. The fault plane is usually curved.

Associations of faults and tectonic structures

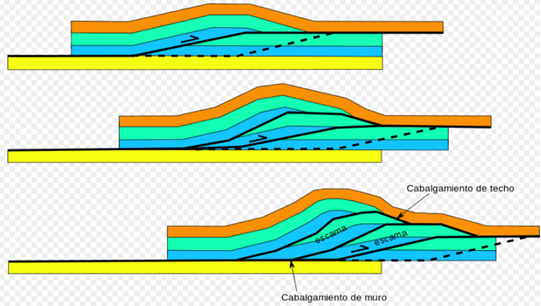

The structures linked to the faults depend on the type of regional tectonic regime in which they have been formed. However, there are some forms and terms common to all of them: it is common for faults to vary in their route, showing relatively horizontal areas, landings, alternating with more inclined areas, ramps. The blocks delimited between fault ramps are called tectonic scales or horses and the stack of these scales is called duplex.

In regions of tectonic extension

In a regime of limited extension and in conditions of fragile deformation systems of normal faults are developed staggered, more or less parallel, that form sunken zones, denominated Grabens or tectonic pits, that can alternate with elevated zones, denominated Horst or tectonic pillars.

In regions of tectonic compression

The most common forms associated to the compression are produced by inverse faults: thrusts and shifting mantles, typical of the external zones of the collision orogens, in what is called «belt of thrusts» and corresponds to the tectonic style of skin fine.

In areas of tectonics

In large tearing faults, whose displacement component is mainly horizontal, local compression or extension areas can be delimited that produce lifting or sinking movements. The relay or bridge between two nearby faults or the local curvature of a fault in direction produces an area in which the local direction of the fracturing is oblique or perpendicular to the direction of main displacement, forming scales and associated duplexes.

Gravitational failures

They are those that are produced exclusively by the effect of gravity, not by the performance of tectonic efforts. They can occur in different geological contexts:

- Mid-oceanic ridges, where they delimit the mid-oceanic rift.

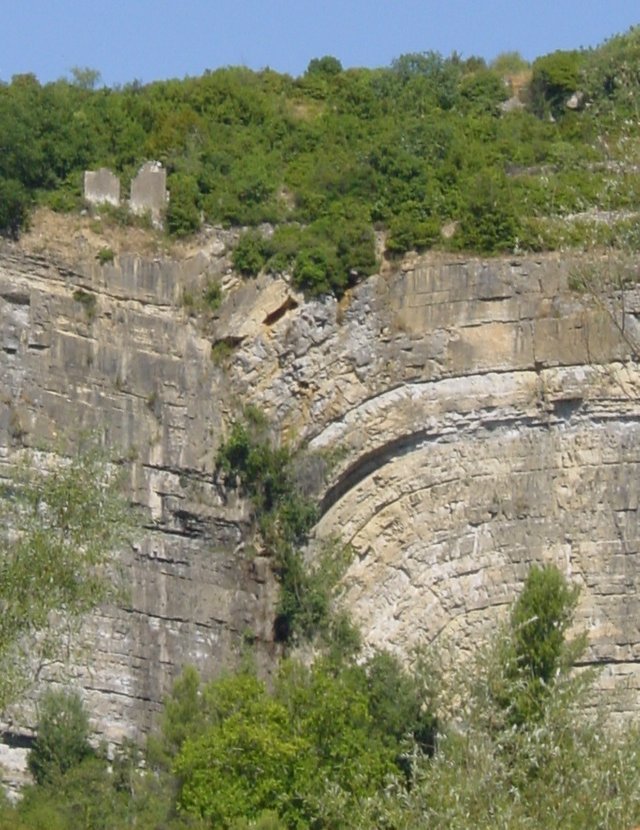

- In karst terrain, due to the dissolution of the substrate or the collapse of cavities.

- In volcanic regions, by collapse of magmatic chambers or sliding of unstable volcanic buildings.

- On steep slopes or slopes.

Fault Rocks

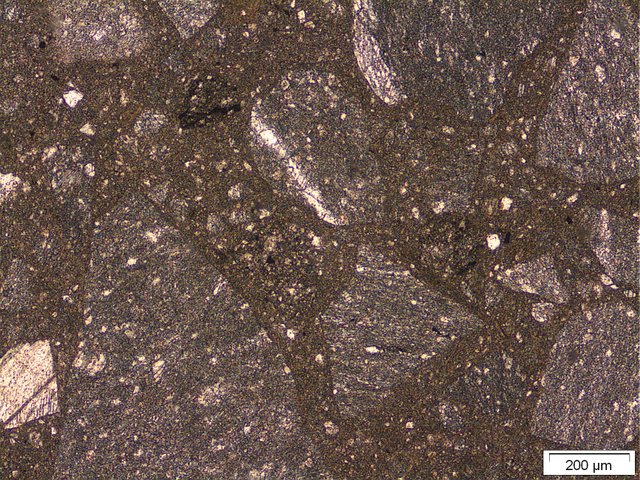

In many cases the friction in the plane of failure produces the crushing or deformation of the rocks that form it. The deformation band can reach several tens of meters thick. Depending on the training conditions they can be of different types, among which there is a continuous gradation:

In conditions of fragile deformation, the fault gaps occur, when the fragments (clasts) are visible to the naked eye, or the flours of failure, when the clasts are microscopic.

In deeper conditions and with higher temperatures, cataclasites are formed, which are rocks with a greater cementation than the previous ones. If the friction of the fault increases the temperature, up to the point of fusion of some of the finer components of the rock, pseudotachytes, dark rocks with a vitreous texture, can occur.

When the deformation occurs in the ductile or fragile-ductile domain, under conditions of metamorphism, the mylonites and ultramilonites are produced, which define the shear bands, with a characteristic banding of the rock.

Morphological features of faults on the Earth's surface

The following features are usually useful to identify faults in the field:

Scarp failure: is the morphological feature produced on the surface of the earth due to the displacement of a fault. They constitute rectilinear morphologies through which the topography varies abruptly. We can distinguish three main types:

Primitive or original failure scarp: when the scarp is recent or has not yet been dismantled by erosion.

Fault line scarp or derivative: when the blocks involved have been eroded and the original failure jump is not conserved or the relief has been inverted by differential erosion.

Compound failure scarp when the fault has been reactivated and the blocks involved have suffered differential erosion.

Triangular or trapezoidal facets: they are forms associated with fault line escarpments or compound escarpments due to erosion, by the intersection of gullies or valleys perpendicular to the rectilinear plane of a fault escarpment and oriented towards the sunken block.

References Bibliography :

Anguita, F. and Moreno, F. (1991). "Tectonics". Internal geological processes. Editorial Rueda. pp. 103-137.

Mattauer, Maurice (1976) [1973]. The deformations of the earth's crust [Les deformations des materiaux de l'ecorce terrestre]. Methods Barcelona: Omega Editions. p. 524

Agueda, J .; Anguita, F .; Spider, V .; López Ruiz, J. and Sánchez de la Torre, L. (1977). «Tectonic processes». Geology. Madrid: Editorial Rueda. pp. 221-272.

Tectonic faults

Vicente, G. de (2009) "Illustrated guide of the alpine thrusts in the Central System» Reduca (Geology). Regional Geology Series, 1 (1): 1-30

failure escarpment. Glossary of Geology. Royal Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences.

Coque, R. (1987) [1977]. «The elementary structural forms». Geomorphology [Geomorphologie]. Alliance Textos University 79. Madrid: Editorial Alliance. pp. 46-73.

Earthquake Hazards Program (2012). «Active fault» (web page). Earthquake Glossary. Geological Service of the United States. Retrieved on January 27, 2014.

Although an informative article: Do not forget to cite your images!

@originalworks