Loot Boxes and Crack Addiction

Loot Boxes are now a staple for most free-to-play games. Recently, they have also cropped up in games where players have already paid full price for their game. The idea behind a loot box is that for a tiny sum of money, players can test their luck in opening a randomised box that may or may not have something good in it. These boxes may have items that are purely aesthetic or may improve in-game performance. I will be discussing the overall concept of the loot box with its psychological implications. I will touch on not only the loot boxes in online games but also the loot box equivalent that might as well have started it all – card game packs.

Disclaimer: I am not a psychologist. I am just sharing what I found online. Things online may not be the truest so in the end, it is your responsibility to read up on the topic. Should I dispense any advice, it would be my opinion, not professional advice.

My Own Experience with Loot Boxes

My first encounter with the loot box system in an online game was Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CSGO). In this game, you can buy cases which contain one of random ‘skin’ in the set. A ‘skin’ is an item that changes your in-game item’s appearances. In the case of CSGO, a skin would be used to pimp out your guns, knives or gloves. This was because of a choice made by the Valve Team when it came to player customization. Due to not being able to see your avatar from a 3rd Person POV, they decided to make any aesthetic upgrades limited to what you can see in the 1st Person.

Another experience with online loot boxes I’ve had is Hearthstone. This is a free-to-play game that is essentially Magic: The Gathering Lite with more RNG. In Hearthstone, players can open digital booster packs containing 5 cards of any rarity. This can be paid for by in-game currency or real-world money. This is an example of the loot box system being integral to gameplay as the more packs you buy, the higher the chance you have the right cards to build the best decks.

Now, onto my offline experiences with this concept. I grew up with Pokemon. The game where begging my mum to buy me booster packs might as well have been a part-time job. However, I have since mostly graduated from that game due to the rampant counterfeiting scams that happened in my school. It was unpleasant to find out that your cards were worthless because someone else scammed you out of your real cards after beating you with their fake ones. I wasn’t the smartest kid on the block. It was very interesting that counterfeiters even started making fake booster packs! So, kids would end up buying the fake product for a few bucks PER PACK instead of a big box of cards.

However, now my life-destroying hobby of choice is Magic: The Gathering. Booster packs can be bought to help improve your deckbuilding. Each booster pack contains a randomised assortment of 15 game cards which may or may not be worth anything to you.

History of the Loot Box

I was looking around for the history of the loot box concept and I found its roots in China. Like all things in the world nowadays, Loot Boxes were Made in China.

According to Danwei, a Chinese MMORPG had the concept for loot boxes in the form of treasure chests that you could use keys to open. This was in 2007. That was more than a decade ago!

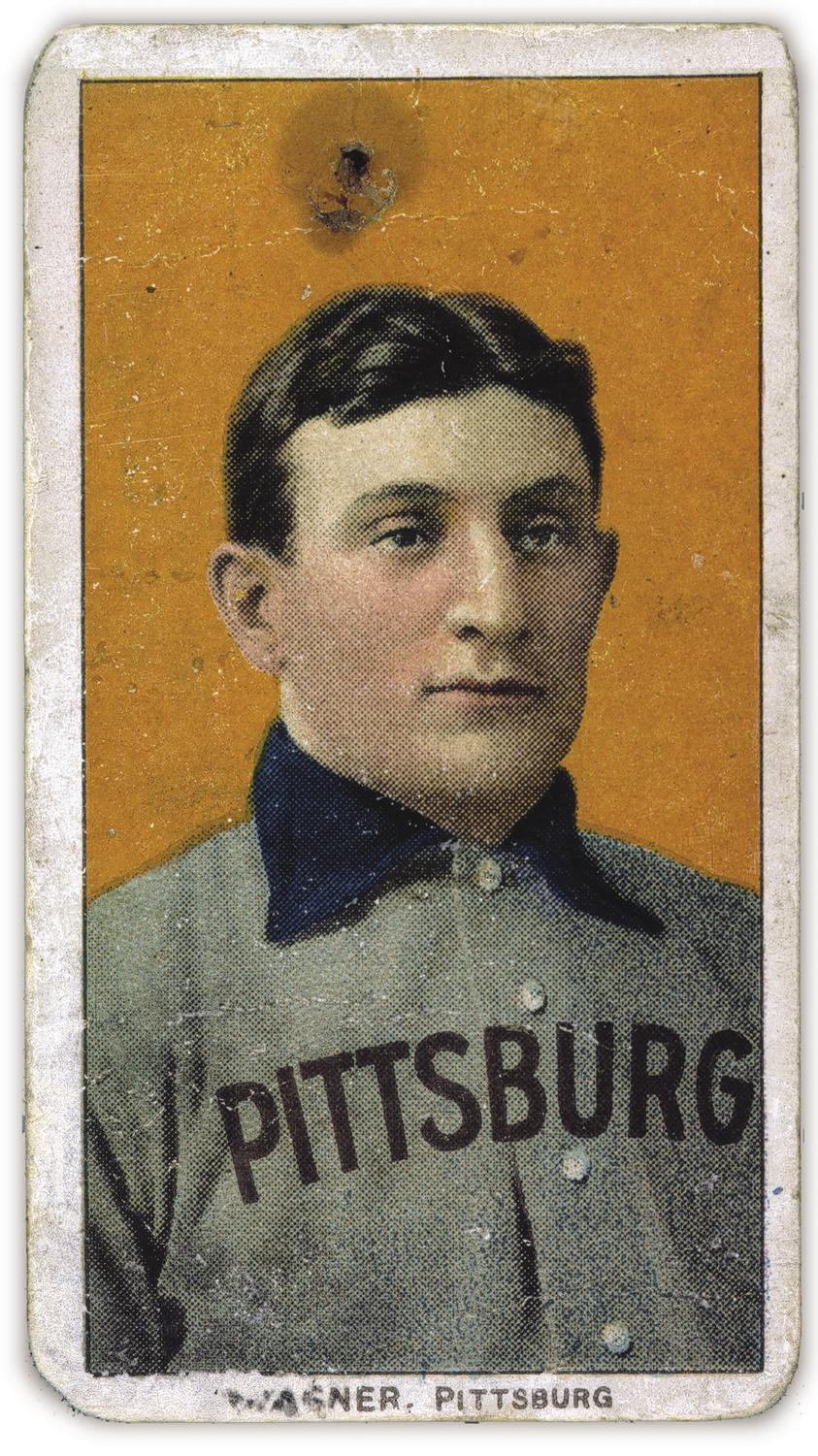

The origin of the whole concept of randomized openings I believe stems from Baseball Cards. The oldest known one I’ve found online dating back to 1860. Eventually, this idea of collectible cards with different rarities created its own economic climate. This is especially apparent in more recent card games like Magic: The Gathering where the secondary market has people by the balls.

Psychology of the Loot Box

Now that I got that out of the way, let’s dive right into the ‘Why?’ of things. Before that, we will be honest with ourselves, loot boxes and booster packs are all gambling. Thus, we can use some psychology associated with gambling to identify why we are so addicted to this system.

Thus, we will discuss the variable-ratio schedule that is applied to gamblers. The idea behind a variable-ratio schedule is that players are expected to win once every few rounds. The difference between each win is randomized to a certain extent. This leads to a high and steady number of attempts at playing. Players have no real idea when they are going to win next. For all they know, the next box they open will have that ultra-rare item.

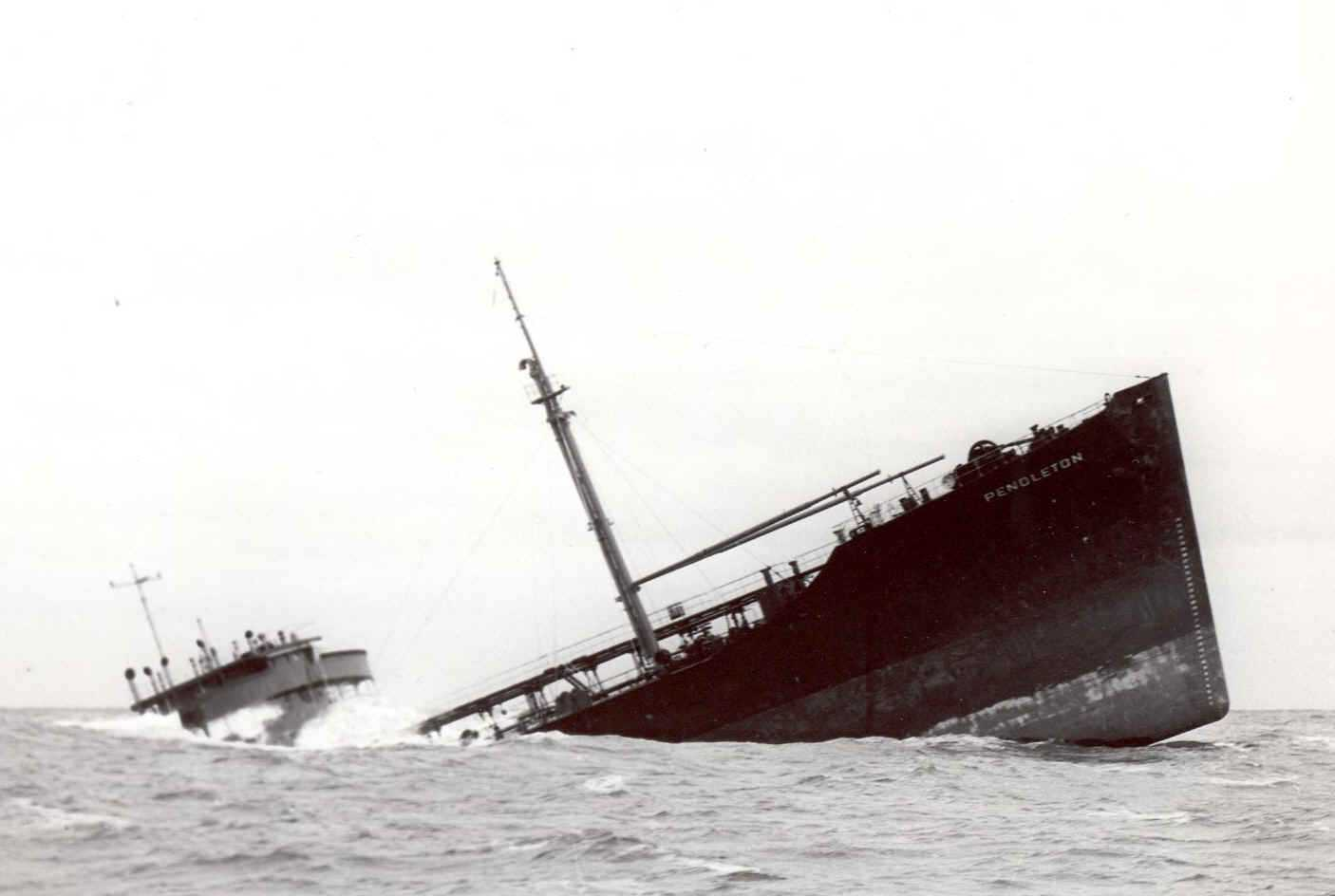

This is similar to a psychological fallacy that is abused in Loot Box Systems – the Sunk Cost Fallacy. It is a beautiful form of self-delusion where people end up investing more in something that they have already invested in. Because players refuse to admit that they are at a financial loss (that their costs are sunk), they think they can continue to invest in loot boxes because they were already emotionally invested in the game and they think that more money going in will bring back higher returns. Even if the ship has already sunk.

Past costs should never influence future decision-making as this would lead to people unnecessarily buying in when they should have been pulling out.

This leads to the Gambler’s Fallacy. This is where a person believes that past instances will lead to predicting the outcome of the next one. This especially present should each roll occur independently from each other. This may not apply to all Loot Box systems as some of these systems have built-in pity timers.

For example, in Hearthstone, despite not being acknowledged by the devs, there is a pity timer. This timer will ‘force’ a legendary card opening every 39 packs. However, in Magic: The Gathering, even though you are guaranteed foils for each rarity in a box (except for mythic rares and rares being only one of either), there is still some disparity between the value of what foil you might open. This is because of the state of the secondary market with some rare cards being worth more than others.

Loot Boxes also lead to superstitious behavior. According to Skinner in 1947, pigeons exhibited superstitious behavior before receiving food at regular intervals. They would have their little dance, thinking it mattered, even when food would come at normal times. This was because they thought that the superstitious activity could have contributed to the outcome – food. Similarly, in loot boxes, people tend to have their superstitions, whether it is changing some settings in-game or wearing a pink thong while opening their boxes. In the end, this repeated action reinforces the idea that their superstition works once they get lucky while doing it. Then, this adds another layer of enjoyment to the person who is addicted and reinforces to them that they may have ‘broke the game’. This would make them buy more since they have become more confident with their luck.

Another phenomenon as pointed out by Dr. Luke Clark of the University of Cambridge is the concept of near wins. This is done by clever placement of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ by making the big win closest to the biggest losers on the wheel. This is very evident in CSGO as when you are opening a case, a wheel spun but the outcome is already set. The wheel will slow down until it hits a knife skin only to slightly veer to the right and end up with a Consumer Grade P90. It isn’t the Devil mocking you with bad luck but rather insidious design. This is because the near-miss would encourage people to continue rolling despite each result being on its own. Players would think that they were ‘this close’ to winning, even when they weren’t close at all.

The Endowment Effect is also at play in games with collectible elements. This is because people tend to value things they own at a higher value than they are. In the context of Loot Boxes, they think what they open is decent enough to warrant another shot rather than being distraught at how low the value is.

There are many other psychological factors that would further strengthen the point but I think I have already proved it. Loot Boxes were designed to be psychologically manipulative and everyone, me included, fell for it.

Conclusion and Advice

In conclusion, loot boxes are pretty messed up in terms of how they are designed to take advantage of the feeble minds of man. This is not limited to loot boxes. Every successful consumer product does have elements of psychological manipulation. For example, colors of a restaurant logo making people hungry.

However, despite this, it is fine to engage in consumerism. It is fine to open loot boxes. It is fine to open booster packs. Heck, I will be opening many booster packs in my lifetime. Asking people to stop won’t do anything for anyone. Instead, I encourage you to go out there and understand what is influencing your behavior. You are still going to be duped by it but at the very least you would know why.

Overall, my article is a very simple insight behind the design of this recently popular phenomena. Thus, there may be a risk that I have oversimplified things in order to help myself understand the topics. So, my main takeaway from this article is more on this. Be curious. Be hungry. Find out all the facts. Chase down all the information. Just like GI Joe says, "Knowing is Half the Battle."