The Character Problem

Characters are a central part of stories and the way in which we perceive our world and ourselves. They fulfill psychological needs for us. We identify with them, and in many ways see them as we would any other person. Which leads to what I'm referring to as "the character problem" which is maybe not quite so dramatic as it might seem at first.

Characters in games suck. At the same time, characters have an immense importance in our life.

Game designers and storytellers often have to take a step back from conventions and analyze the fundamental essence of what a thing really is.

Characters in particular are something that have stood out to me as a game designer, because of the fact that they are both essential to telling stories and can be portrayed in hundreds of thousands of different ways without really hitting on what matters for them.

The Reality of Characters

When I think about characters, I often find myself thinking of the story of Jekyll and Hyde, both because I have a background in Romantic/Gothic literature, but also because it's a good idea for how we get to know characters.

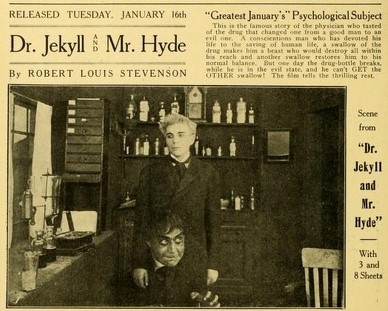

Advertisement for the 1912 Jekyll and Hyde film, which you can watch here.

Jekyll is a known figure at the start of the story, but Hyde is not, and much of the drama in the tale comes down to figuring out who Hyde is and what ties he has to Jekyll (spoiler: they're the same guy). The tale is enthralling and captivating, and I feel it illustrates an important and obvious point:

Characters are not people.

However, from Chick tracts denouncing D&D for encouraging a breakdown of the distinction between fact and fiction to the hyper-emotional reactions that occur when favorite characters die (or are portrayed differently, as anyone involved in Star Wars recently can tell you), one could be led to believe that characters are actually very real.

In Jekyll and Hyde, we get to see ostensible people (the characters of the story) begin interacting with someone who is not connected in the same way as any real person would be, since to live requires a birth, and a birth requires a mother, and people tend not to be able to survive the tender stages of infancy without someone taking care of them.

Even Prospero's daughter Miranda (in Shakespeare's "The Tempest") is aware of her role in the world, stranded as she is on a desert island. Hyde was a unique phenomena, because he was a being out of time and place, more so than even Frankenstein's lonely, abominated creature.

And it is for a reason that I say that Hyde was a unique phenomena, because many games create characters just as divorced from their setting's reality as Hyde was from his.

The reason why we have a hard time distinguishing between characters and people is simple:

We see characters as we see other people. There is very little distinction between fact and fiction in how we perceive characters and people, because the divide between fiction and reality is arbitrary and flows from necessity (we would have very real, very immediate consequences for thinking that we can cast magic spells that allow us to fly and then jumping out a window while attempting to do so).

Humans are wired to attach to others and form emotional investments, and when we see a character in a movie or read about them in a book they become very real to us, because they are real to us in the same sense as anyone else in reality. If we can watch a character do things, and think and reasonably picture them interacting with us, that's not all so different from how we interact with other people in reality.

In fact, many characters are more real to us than other people, because we see them go through more emotional turmoil and more tests of character than most people we will meet. It's not considered voyeuristic to watch a character do things we wouldn't watch real people do, and we don't owe them assistance when they go through a rough patch, which sates a couple other problems that we would have when getting as involved with real people as we can with characters.

It is largely for this reason that we have always seen myths and stories, and why we still remember the myths and stories of ancient people when we know almost nothing else about them. In a sense, nothing is more human than a character, nothing can be more sacred.

But, of course, they are figments of our imagination. They represent parts of us, parts of our being, and–more so than people themselves–our relationships to other people.

Characters in Games

As a game designer, I often feel like we take the wrong approach to characters in games. We model them solely after criteria which we might assess in ourselves; strength, sex appeal, energy, and skill. We think of others in this way as well, so it's a logical starting point.

However, a quality-focused outlook ignores the relational standpoints that we would use to assess other people; we may not think of ourselves first as someone's child or spouse or parent, but that becomes critical as a way for us to assess human behavior.

I'm certainly guilty of making games that focus on this, and from a strictly mechanical standpoint it's difficult to show relationships. Often games deal with this as an afterthought, or encourage players to make concessions to characterization only in footnotes.

The real ways that we think about characters, if we wanted to use them to tell stories well, focus on their connections. Stories need to go through some process of revealing the unknown, but they also need to stay connected, and often the focus on our narratives is on exploring in a very literal sense.

I'm not saying that the classic explorer who strikes out into the unknown is a bad character automatically. There is a lot of room to build on that, and there are examples (like the Tomb Raider reboots) of this being done with superb skill and execution. At the same time, we need to look at the places where this is done well, and note what the key similarities are.

Almost universally, the similarities in strong characters are their connections to others. Even the (very literally) two-dimensional Mario has Princess Peach to rescue.

We don't care what Mario's Jumping skill is, or what his Movement Speed is in pixels per minute. I have very rarely cared to start off describing a D&D character I've played by announcing their Armor Class proudly (and I can build some very good defense-oriented characters).

In order to tell good stories using games, we often see games lose mechanics, which can have problems of its own; part of the appeal of games is the ability to have skill, and a game being simply a choice engine where players choose between two possible outcomes is not going to be satisfying in the same way as a game which relies on skill and chance–these mechanics serve as a grounding force, allowing a safe basis from which to go out and explore the world in a way that a character defined solely by their connections cannot be rooted.

So it is necessary to hybridize characters that are conceived of as a culmination of connections (which works fine in non-interactive narratives), and characters conceived of as qualities that are mechanically represented in a system.

I'm also not a fan of "contact" systems (such as those in Shadowrun, which I otherwise cherish fond memories of), as they don't encourage a real relationship so much as a way to use other people in a strictly mechanical sense. A good roleplayer can overcome this, but it tends to lead people in the wrong direction.

A good game makes characters connect in meaningful ways that are both inherently valuable to players and provides opportunities for growth.

The Cortex Plus system (affiliate link) actually does a good job of this, but the Smallville Roleplaying Game that was the best example of this in practice is no longer available. In the game, characters had ties to other characters and also to values that represented what they believed in. While this was handled in a largely mechanical way, it was something that really encouraged characters to come to life in a way that the more intrinsic qualities don't do.

There are other games where characters' roles in other peoples' lives have mechanical representations–I'm a fan of how Degenesis (warning: site is NSFW, nonsexual nudity) has each character choose an archetype to reflect their personality and social role and defines them in terms of their social rank (though the exact execution of the latter can be limiting rather than enabling) within their society.

Wrapping Up

Characters are as meaningful to us as people, and that's a good thing. It allows us to more easily learn vicariously from the decisions they make and learn the lessons that would otherwise require a painful violation of privacy and great personal losses on the behalf of people we learn those lessons from.

On the other hand, as storytellers and game designers we can often lose sight of the role that characters play in our understanding of the universe, and forget to provide our audiences with characters that satisfy their needs.

To create characters that can tell lessons, we need to create characters that are tied into their universe, and in a way that connects them to other characters.

Congratulations! Your post has been selected as a daily Steemit truffle! It is listed on rank 14 of all contributions awarded today. You can find the TOP DAILY TRUFFLE PICKS HERE.

I upvoted your contribution because to my mind your post is at least 8 SBD worth and should receive 92 votes. It's now up to the lovely Steemit community to make this come true.

I am

TrufflePig, an Artificial Intelligence Bot that helps minnows and content curators using Machine Learning. If you are curious how I select content, you can find an explanation here!Have a nice day and sincerely yours,

TrufflePig