[Role-Playing Games] GM-full Gaming That I'll Endorse

Or how I stopped worrying and learned to love the bomb.

In the last major work on gaming that I posted to Steemit, I talked about GM-less play and went in depth talking about a few examples, because I figured it's a fairly rare field of experience. And also because it's my preferred, personal, mode of play.

But just because it's my preferred mode of play doesn't mean that it's my only mode of play. Every once in a while, for a game design which is particularly good, I'm happy to sit down and either run a game or (far more rarely) get to play in a game. Those moments are special. Not only do they simply not happen that often but they typically only happen at conventions and as a result almost entirely with strangers.

Power and Distribution

As I had said in my earlier article, there are things which GM-less play is simply not good at doing, or at least not as good at doing as with more traditionally architected games.

Authority and Resposibility

Go through the checklist from the last article if it's not fresh in your mind.

For me, the most important thing that you can get from more traditional systems is the sense of direct character focus. Sometimes the Authorial narrative position is just not what you want to do that day. Thinking about the story from a broader perspective is not what you want to do that day. Sometimes, you just want to sit down and play a character – or, conversely, you just want to sit down and have other people play in a world that you're running.

There's no shame in that game. That is a perfectly reasonable desire to possess, and if we're honest with ourselves, it's the desire that most of the gaming industry really expresses. It's straightforward. It's uncomplicated. Everyone's responsibilities are clearly delineated. It's awesome for what it does.

Crunchy Nugat

My taste in this sort of thing is, predictably, still angled more toward flexibility and narrative control than mechanical crunch and specificity.

I have an inherent aversion to crunchy systems. Sure, I have a copy of the Big Blue Book edition of Champions on my shelf. What self-respecting role-playing game collector doesn't? (I even have the 5th edition, which has more in common with the thickest of college textbooks than an RPG.) I have a metric ton of early 90s White Wolf role-playing games, with all the nightmarish complexity that Storyteller always promised it wouldn't bring, and yet provided some of the most crunchy, most twisty mechanics of the era. I even have Jovian Chronicles, which I absolutely adore – in part because it has one of the most terrifyingly crunchy mechanical systems out there for designing and building all kinds of vehicles, from personal skateboards to giant robots to star jumping spacecraft.

The Right Tool For the Right Job

But "the right tool for the right job," and crunchy mechanics have a very specific power that they bring to the table: the more mechanically rigid the system, the less trust you need to have for the other people at the table when it comes to resolving conflicts.

In a sense, you can think about "trust" as the real currency that goes around the table when you're playing an RPG. I write a lot about trust, I think a lot about trust, and much of that emphasis on trust comes from decades of spending time with people who are close to me and complete strangers, thinking about how that trust affects our experience and how trust can be controlled to improve that experience.

Mechanical rigidity lets everyone know up front how they can interact with one another, and specifically about the bounds and limitations of having different opinions of what should be happening at any given time. For the primary market of role-playing games over the last 50 years, teenage boys just trying to figure out where they fit into society, that is a huge deal and it's always been a huge deal. That structure, that rigidity, gives them bounds within which they can "strive together one against the other as brothers."

The rules act as arbiters and constraints, and provide a guide as to what one can reasonably hope to attain, can reasonably ask for, and how that request can be denied without a loss of face or personal grudge on either side.

(For those who have been following along, it's worth pointing out that GM-less games can also be quite "crunchy," in the sense of having a very strict mechanical architecture for resolving inter-player conflict. Polaris, for example, has extremely rigid and ritualized mechanics for negotiating the direction of narrative – and it is those rigid and ritualized mechanics which allow it to distribute trust in an environment where it might not otherwise exist.)

Conflict at the Core

These days I generally don't want the rules to replace other ways of resolving conflicts. A certain level of conflict is actually required for my full-throated investiture in the play experience. You might read this as pressure against my previously stated highly cooperative focus and role-playing games – but I don't see it that way.

Certainly not everyone wants or needs implicit conflict at the table outside of narrowly defined roles. Traditionally architected GM-centric games put the GM directly in the adversarial role, and everyone at the table knows it. It's his job to bring the conflict every time, every day, every session, so that the story can happen.

As I've said, that's a lot of work.

This dynamic between conflict which is necessary for a story and distributing the responsibility for bringing that conflict across the group is one of the major differences between GM-less gaming and more traditional gaming.

I want to cooperate with the other people at the table. I want to make the story that speaks to all of us. Simultaneously, I want to challenge and be challenged; I need that for my investiture. In traditional games the channels by which these things run are consistent.

We're going to talk about two different role-playing games today and even make characters for them – because nothing really reveals the quality of an RPG faster or more completely than the experience of character generation. It's the first thing you do in of traditionally structured game. It's your introduction into the world. It's your first major decisions that have real heft.

So let's get on that.

Building a Better Mind-Trap

For some people, myself possibly among them, creating characters is one of the most rewarding parts of the "lonely fun" portion of being involved with RPGs. You can do it by yourself. You are engaged in an act of creation. There is mastery to be displayed, especially in some of the cruncher systems, by going through the methodology step-by-step and coming out the other side with this thing that is uniquely yours.

That is a compelling thing, and it's not surprising that some people spend an amazing amount of time just cranking through the process over and over to make things to show to other people. To the point that a number of game developers have (only half-jokingly) talked about getting T-shirts emblazoned with:

DON'T TELL ME ABOUT YOUR CHARACTER.

So it goes.

I am going to tell you all about my characters. Just buckle in, grit your teeth, and enjoy the ride.

Wushu: The Ancient Art of Action Roleplaying

If that's not a title that fills you with an already exploding level of excitement and desire to know more, I'm not sure you're alive. Please see your doctor.

Wushu is my go to – without question, without hesitation, without even blinking for a moment – role-playing game for anything that involves anything if I think that I might want to run the experience as a GM. In fact, if anyone nearby is running a Wushu game, I will inevitably be drawn to it like a moth to a flame, drop into a seat at the table, and begin playing without conscious volition.

It's that good.

Mechanically, it's pretty open. Characters have Traits which are short descriptors with a numeric quantifier 1-5 (and you're going to see this a lot in games that I like). The GM has a pool of tokens which represent the Threat of a scene (or an actual Big Bad which is built very much like the characters and has the same resources to call on). During a given scene, players describe exactly what their characters do and allocate d6s for every meaningful detail in the description, and at the end of this description phase you decide which go to offense and which to defense, then all the d6s are rolled and compared to the controlling Trait. If you roll equal to or under the Trait, that die is considered a success and offensive successes destroy Threat on a one-to-one basis and opposed roles between characters function in much the same way. A collection of successes only determines how effective the described actions were.

Let me repeat that, because this is where things are really different than you might be expecting:

Everything that you describe your character doing, your character does. They achieve it. They accomplish it. That happens. If you narrate them, "jumping into their nearby car through the window, shoving off the steering wheel through the opposite window straight into the face of two oncoming goons, landing an elbow into the nose of the guy on the right and a knee into the groin of the guy on the left, then dropping down to the bad ass superhero three point stance?" That's exactly what happened. Unless part of your narration violates something everyone at the table has agreed to, there's no debate about it.

(Also – that description would get you the maximum 6d6 possible roll and has a good chance being effective at whatever you were trying to do.)

Wushu is currently free. Let that sink in for a minute. This is a role-playing game that I bought when it came out, and then I bought all of the supplements as they came out, and I have absolutely no regrets having done so, even knowing that you can get it right now for absolutely free with everything that I paid for. That's how good it is.

Now let's make a character.

Jason Malloc, Hot-Shit Decker

I love ShadowRun. I played so much ShadowRun in high school that it physically hurts to think about it. The awesome hybrid of crazy magic, nanotechnology, invading spirits, nods to Tolkien-esque fantasy – amazing. My favorite character back then was a double dome geek who part magical engineering theory at MIT&M and was only a shadowrunner during the summer breaks, just for fun and a few extra bucks.

Did I mention that he was afraid of heights and owned a hover-panzer? You'd be surprised how many more times the first comes into play than the latter.

But I digress – because we're not going to talk about that character. We're going to create a brand-new character who would be perfectly at home in any ShadowRun game.

Let's go with the guy who is very traditional decker; he's a down on his luck, living on the street, code slinger who is not above doing a little digital breaking and entering to make a fast buck.

We'll go through the very basic and straightforward character creation process rather than the point allocation system, even though both of them are awesome.

First up, Motivation.

Motivation - Why does this character fight? Make it specific, like "End the False Emperor's Tyranny" or "Keep my Ship Sailing." A good motivation tells everyone where you want this character’s story to go and it only kicks in at truly dramatic moments. Give your motivation a rating of 5, so the character is always at their best when it counts.

Jason seems like the kind of guy who's always looking for the next big score, the next big thing, the next – well, anything, really. So let's make "looking for the next big everything" his Motivation, which automatically gives it a rating of 5.

Action! - You’re not a wuxia hero if you’re no good in a fight. It’s important to put a particular spin on a character’s fighting style, since all heroes will be equally competent. Classics like "Preying Mantis Style" and "Buddha’s Palm" are excellent choices, as are broad schools like "Judo" and "Capoeira." (If you’re stuck, see below.) At least make sure you cover an action scene niche like "Parkour," "Speed Demon," or "Kung-Fu Chef." Give your action trait a rating of 4, so your hero can pull their own weight.

This guy's been living on the street – or close to it – scraping along for quite a while. Think about Case at the beginning of *Neuromancer. He wouldn't have made it this long if he didn't have some kind of inside line on staying alive.

I'm not really crazy about purely heroic characters, if you hadn't picked up on that yet, so how about we go with something visceral? "Fights like a rat in a corner – all the time." Jason will do anything it takes when it looks like there'll be blood, whether it's repeated kicks to the groin, stomping a guy's head when he's down, using his cyberdeck as a club (reluctantly)… Whatever it takes, whenever it takes it.

This is starting to be quite the character.

Profession - What does your character do besides fight? Do they have any notable training, abilities, or talents? This one should be broad: "Manhunter," "Respected Elder," "Hacker," "Occultist," "Eunuch Bureaucrat," "Silver Tongue," "Millionaire," etc. Give your profession a rating of 3, since you’re just a bit better than average at these sorts of things.

We already know what this guy is. He's a "hot-shit decker." That means when it comes to punching holes in things in cyberspace, figuring out the best way to slip in through system security, jacking out just before the black ICE turns his brain to silly putty – he's in the know.

But there's more going on here. He's a hot-shit decker. He's really good at it. The GM would be perfectly within the spirit of the rules to only require Jason to bring dice to bear if there's something challenging for a hot-shit decker. Stuff that just some average, men on the street decker can do? Jason can probably do it without even thinking about it. Automatically. It's not important. It's not even interesting.

That's a big deal. This is a place where having a GM who cares about being an advocate for the characters and letting them be cool can have a huge, amazingly fun, impact.

Weakness (Optional) - Weaknesses are funny things. They can add depth to a hero and enforce genre tropes, but characters should consider them Things Best Avoided. Superman doesn’t get any credit for handling Kryptonite, it just kicks his ass. Hence, Wushu players are not rewarded for roleplaying their Weaknesses, they're penalized for roleplaying against them. A Weaknesses is a Trait that’s rated 1. It’s worse than default, but your players should never actually roll against it. They should avoid it, just as their characters would.

Because we're the kind of people that like flawed characters, there's no way that we are going to let this go without having a really neat weakness for Jason.

So far we haven't worked in the fact that the setting involves magic in a significant way. That's kind of a shame. We want to create a weakness for the character which connects him to the world at large but doesn't cripple him for overall interaction.

I idea. How about "terrified of spirit mages and spirit magic"? In setting, Chicago has already been deeply messed up because it was infested with insect spirits. It would be perfectly reasonable for a guy who understands technology to have a certain distrust of the more socially-focused magic of summoners and binders. Wizards? That's just weird science, but talking to alien entities and making them do things for you? That's terrifying.

And we're done. Let's take a look at how things turned out.

Jason Malloc

"Looking for the next big everything" (5)

"Fights like a rat in a corner – all the time." (4)

"Hot-shit decker." (3)

"Terrified of spirit mages and spirit magic" (1)

That's it. That's the whole character. That's everything you need to do to play the game, have fun, and get on with getting on. Is it any wonder that I love it so?

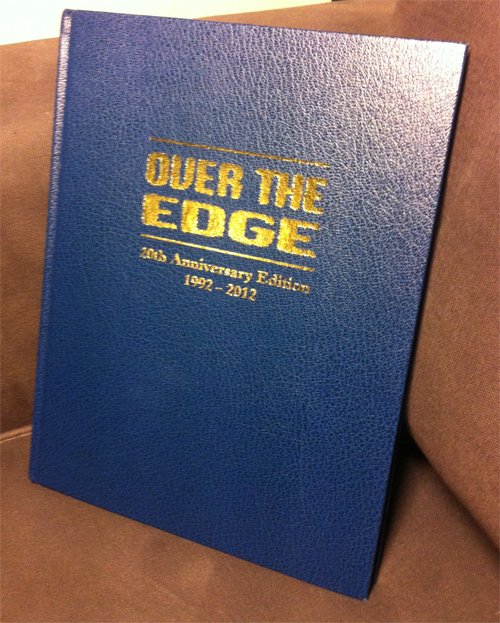

Over the Edge: The Roleplaying Game of Surreal Danger

Over the Edge is one of those games which was way, way ahead of its time. Not only in terms of the basic game design, which in many ways presaged a lot of indie game development for the next several decades, but in terms of setting design, which was explicitly "adult" without fixating on gratuitous sex or necessarily over the top violence but instead on the disquieting surrealism that you might find in a drug addled William S Burroughs novel -- in a very literal sense, because the setting of Al Amarja is explicitly inspired by constructs like the Interzone in Burroughs's work. The island is a place full of bizarre conspiracies in front of a backdrop of Mediterranean weirdness, drug indulgence, aliens, time travel… It's a place where people wear nooses in lieu of ties and that sensibility permeates the whole thing.

Amazingly, this is going to be the second game with mechanics which I can point out are available for free – the best possible price.

So let's take a look over at the Wanton Role-Playing (WaRP) System and have a chat about the mechanics which were pioneered in 1992.

Money for Nothin' and Traits For Free

I said before that the idea of Traits being the central descriptors of characters in an RPG, openly free-form, wasn't original to Wushu. There is a good chance that Traits were really popularized and largely driven by Jonathan Tweet's work on Over the Edge. This may be the earliest example that I can find in my collection of the Trait not proceeding from a static list of "skills" or the like, and resolution being determined by narrative scope of the description.

Resolution is actually quite traditional, despite the extremely nontraditional architecture of the character itself. OTE uses a dice pool of d6s, equal to the rating of the governing Trait. In the event of a test, roll the dice pool, add them up, and compare them to a target number based on the GM's assessment of the difficulty of intent.

Bonii and Penalty

A key difference between OTE and a lot of other dice pool systems is the way in which advantage and disadvantage are accounted for in a particular die test. Rather than add or subtract from the target number, in OTE you include a bonus die or penalty die in the pool. Bonuses and penalties strictly cancel one another and accept in particularly extreme circumstances, the GM should never really allocate more than one bonus or penalty to a given roll.

Reading a roll with a bonus or penalty is easy: an extra die goes in. If it's a bonus, simply drop the lowest die and proceed to add up the remainder. If it's a penalty, drop the highest die and out of the remainder.

In play, this ends up being a really fast and effective method, especially compared to other games of the time. Because you generally don't care about how many advantages or disadvantages apply to a particular test, there is little wrangling about trying to add up each and every little bit.

The probabilities really break down to:

"I think you'll have a better chance to succeed than usual."

"Eh, it's a pretty average task."

"This seems easier to achieve than most things you're qualified for."

Important to note is that the question of whether something should have a bonus or penalty die is considered relative to "most things that Trait would be qualified for," and not necessarily just "this thing would be this hard."

Are you in a circus high wire act and trying to walk across a gap between two buildings on an appropriately tensioned wire? That might not even require a roll if you're not under stress. Is it just a random power line, but there is nothing else particularly awkward about it? A standard test should do. It's the sort of thing that might be mildly challenging. Are there high winds and it's the 80th floor? That seems like it would be more difficult than usual. Do you have a long pole to provide balance? That's probably easier than you're qualified to achieve.

Because there is no question of whether there will be multiple bonuses or penalties, combinational complexity of trying to figure out whether walking a fairly tensioned wire in high winds on the 80th floor while carrying a usefully long pole largely goes away. Do these things mostly cancel out? Sure, it's a standard roll. Does the GM think that, everything considered, things seem a little harder to pull off? Penalty. Does the GM think that this would be a cool thing to happen, and it serves the story and what everybody at the table would enjoy? Bonus.

And then play proceeds without the usual bickering over minor adjustments to something everybody wanted to happen anyway.

Arleen Spector, Freelance Combat Acccountant

Enough of mechanics, let's get stuck in and make a character!

Concept

First, get an idea of the character you will portray. Have a good idea of who you want to be before you start any details. An example concept might be, “A psycho-killer commando who escaped from CIA brain-washing program when the programming failed.”

Al Amarja is a weird place. Corporations and conspiracies, aliens and outsiders, weird drugs and weird people who are selling said weird drugs – they all mingle, just as criminality and corporations, the street and High Street. Sometimes all those weird people have weird problems, the kind that only someone with a degree in chartered accountancy can solve.

Of course, when you're digging in the black books of a human spleen trading organization at the behest of their criminal superiors, sometimes people don't like you. Sometimes you find yourself in a little over your head.

That's when you're glad you're a combat accountant.

Traits

Each character has four traits. One trait is the character’s central trait, usually defining who that character is. Two traits are side traits, additional skills or characteristics. Of the above three traits, one is chosen as superior. The last trait is a flaw or disadvantage. Each of the

four traits entails a sign, some visible or tangible aspect of that trait.

This is pretty straightforward, and thankfully so. While there's a lot of "specific terminology", at least they're using words which mean something that is close to the original meaning. All too often that's not the case in a lot of indie games.

What may not be obvious and yet is really important about this discussion of Traits is the focus on signs, something visible about the character which denotes that they have that Trait. There is no pre-existing list of signs just as there is no pre-existing list of Traits, so whatever manifestation that settles in your mind can be what the character sports.

It seems like a small thing, but reflecting the characters internal state externally, in a way that everyone at the table can engage with, provides a lot of hooks for other people to do just that.

Central Trait

First, you have one central trait, essentially your identity — who you are, what you do. This trait can take into account a variety of aptitudes, skills, or characteristics. When you, as a player, describe your character, you are likely to use this trait as the central concept. For example, “I’m a model,” or “I’m a former secret agent.” If you want to be something weird, this trait must cover that identity.

A central trait includes the name of the trait followed by a description, then in parentheses sign(s) that are associated with the trait. Numbers at the end of the description indicate the number of dice that would be assigned to that trait normally (the first, lower number) and how many dice would be assigned if it is the character’s superior trait (the second, larger number; see later for an explanation of superior traits). If the scores listed are “4/6,” this represents higher than normal scores for “narrow” traits. See that optional rule later in this section.

You can see some of the era in which OTE was written breaking through here, with a lot of discussion narrowing what is meant by any given term. This exists just to enhance the feeling of trust available at the table to everyone, especially because so much of the experience has been defined as free-form.

But let's talk about Arleen.

It's pretty obvious that we need to go with "Combat Accountant" as a central trait. Frankly, it's too cool not to make important mechanically. Everything I character sheet is really just a flag to attract the attention of other people and the GM to something which should interest them and which you, as a player, are interested in being part of the story.

Combat Accountant – covers advanced forensic accounting techniques including knowing how to tell if someone has cooked the books, tracing pseudonymous transfers through the blockchain, staying awake doing boring things for long hours, and effectively being able to engage in small arms combat while keeping your head down. (Really advanced cell phone with the case covered with pictures of dollar signs.) 3/4

Side Traits

Once you have your central, identifying trait chosen, chose two side traits. They may or may not be related to your central trait. Unlike the central traits, these side traits are very specific, representing discrete characteristics or skills.

Just because a trait is your “side trait” does not mean it is insignificant to your character. For example, a professor with the side trait of “hack writing” might be pursuing her writing career, and her attempts to gain inspiration for her fiction may be more important in play than her teaching career. Indeed, she may be better at writing than teaching.

A side trait includes the name of the trait followed by a description, then in parentheses sign(s) that are associated with the trait. Numbers at the end of the description indicate the number of dice the character receives for a normal and superior version of that trait, respectively. If the scores listed are “4/6,” this represents higher than normal scores for “narrow” traits. See that optional rule later in this section.

Side traits are intended to be less broad-spectrum than your central trait, and the tension between those two elements really helps illuminate your intentions for the character. As the text says, side traits are not necessarily of lower quality in your central trait – you can certainly be better at something that's in your side trait than your central descriptor.

Let's put a couple of interesting side traits which should help carve out what we're going for here.

Monkeyshines – Tomfoolery. Shenanigans. Pranks. If it involves fooling people for comedic value and possibly just a little bit of embarrassment, it's game on. Covers hiding in office furniture, concealing water balloons, stealthily placing whoopie cushions, and maintaining a deadpan expression. (A tattoo of party balloons and confetti on the inside of her left wrist.) 3/4

Long-Distance Runner – it's a long way to temporary, but Arleen can probably run the whole distance. Covers breath control, making sure she stays hydrated, finding quick places to go to the bathroom outside, truly terrifying endurance, and just absolutely, positively, will not stop – running. (Extremely well developed and shapely thighs.) 3/4

Scores for Traits

Now you have your three positive traits: one central trait and two side traits. Next, you must assign a score to each. The score represents how many dice you roll when using the trait. Two factors determine your score for a given trait: whether it is “superior”, and whether it is the kind of trait that most people normally have. (See also the optional rule for “narrow” traits.)First, you choose one of your three traits to be superior. Choose the one you like the most or think is most important to your character.

Most traits are better or worse versions of traits the average person has. For instance, a strong character is stronger than average, but even the average person has some strength. Some traits, however, are unusual or technical, and the average person has no skill (0 dice) in that trait. If this is the case, a character with this trait has fewer dice than normal, to represent the fact that he would normally have no dice at all in that trait. Medicine, channeling, and quantum physics are examples of technical or unusual traits.

A bit lengthy, but definitely not hard given our selection of Traits.

Nothing here is particularly narrow, especially given the description of the Traits that we provided. The description is hugely important in helping guide everyone at the table to understand what you want to do with a Trait. Consider that Long-Distance Runner certainly could have been a narrow Trait if we had described it as only being about running really long distances. It would've had a penumbra of possibilities but nowhere as broadly as we described it.

That kind of flexibility is one of the reasons that I really love this core system.

Now we need to figure out which of these traits is Arleen's superior trait because that will lead directly to us assigning scores.

From my perspective, it's pretty obvious that Combat Accountant should be the central Trait. It's the part of the character that I find most interesting, it will get us both in and out of trouble, and it really describes what I think of as the core element of the character within stories I want to experience about her. Someone else most certainly could've picked Monkeyshines as her central Trait and that would've been an equally valid way to view the character but would have extremely different implications.

So – Combat Accountant will have four dice, Monkeyshines and Long-Distance Runner will both get three dice.

Flaws

Once you have determined your first three traits (the central trait and two side traits), decided which of those three is your superior trait, and assigned scores appropriately, it is time to choose a flaw. A flaw is any disadvantage that your character will have in play. It must be important enough that it actually comes into play and makes a difference. Ideally, your flaw should be something directly related to your central trait or side traits, or to your character concept, rather than just a tack-on disadvantage.

Often a flaw causes one to roll penalty dice in relevant situations. Other flaws cause problems that the player simply must roleplay.

A flaw includes the name of the trait followed by a description, then in parentheses sign(s) that are associated with the trait.

Coming up with a law can sometimes be one of the hardest parts of putting together a character in a system which pays attention to the narrative experience at the table. You want to pick something that is compelling and interesting, but the innate tendency is to try and maneuver into picking a flaw which won't be much of a flaw, either not coming up very often or not really affecting what you do.

That's the wrong approach. You absolutely want to pick a flaw which comes up a lot and which will actually impair you. Every time it comes up, every time it enters the story, it's an opportunity for you to show off clever thinking, to become the temporary focus of the story, and to create disadvantageous positions from which you can look good getting out of.

Arleen is a forensic accountant. That means that she is probably made a lot of enemies in her day, not all of them looking to kill her but certainly a lot of them who would rather not cooperate with her. Let's go with that.

Disgruntled Associates – When engaging with people involved with and especially at the top of organizations with stuff to hide financially, there's a one in six chance that that person has had an unpleasant association with Arleen and is reluctant at best and adamant at worst that she not be involved. (Always seems to be eyeing the door when in corporate or criminal environments)

Hit Points

Your “hit points” represent the amount of punishment, damage, and pain you can take and still keep going. The more hit points you have, the harder you are to take down.

Hit points are determined by any trait you may have that is relevant to fighting, toughness, strength, mass, or other aspect of your character that indicates the ability to take damage. If this trait is ranked as 4 dice, your hit points are 28. If ranked as 3 dice, your hit points are 21.

Lacking such a trait, your hit points are 14. (You do not have fewer than 14 hit points for having a trait like “weak.”)

It's definitely a measure of when this game was produced and how traditional it really is in many ways that we actually have a hit points mechanism. Not a wound level mechanism, not an impairment mechanism, but straight up hit points.

Arleen has Combat Accountant at four dice which gives her a straight 28 hit points. If we really wanted to and we just wanted to milk the rules for all their worth, we could suggest that Long-Distance Runner should give a bonus for increasing her endurance – but frankly rolling random hit points for one Trait or another is kind of tedious, so we'll just take the 28.

Once you’ve determined your hit points, attach a descriptive word or phrase to them to represent what they mean for your character. Forinstance, a strong character might call his “brawn,” indicating that his resilience in the face of physical punishment comes from his well-developed musculature. Another character’s hit points might be “guts,” relating to sheer internal toughness and resolve, rather than to any purely physical trait.

This would be a good time to bring that Long-Distance Runner Trait back in and make the sign for Arleen's hit points "just keeps ticking," referring to her ridiculous endurance. At some point she might pull a John McClane and use that endurance to her advantage.

Experience Pool

As a beginning character, you have one die in your experience pool. This means that once per game session you can use this die as a bonus die on any roll you make, improving your chances for success. Once you use this die, you cannot use it again for the rest of the session.

Simple, we've got one die.

This is also one of the early game systems to use experience as a pool of resources that you can use during an actual game session in order to gain an advantage. Once per session you can use an experience die in your pool to add a bonus die to any role. Handy!

But there's also this:

The experience die represents your experience, will, wits, and special circumstances. You must justify the use of the die in these terms. For example, to block a knife thrust you might say, “This has got to be the third knife-fight I’ve been in this week, and I’m getting used to it.” If

the GM does not tell you what a roll is for, you cannot use an experience die to modify it because you cannot justify its use.

This is another hook by which characterization and narrative is being drawn into having mechanical advantage. But also a way to keep mechanical advantage from those who don't want to engage with the narrative. Over the next several decades, the sort of thing will become almost de rigueur in terms of game design, going so far as to make it into D&D 5th Edition in a variant form.

Motivation

Choose a motivation for your character. Why have you come here? What do you want out of life? What are you trying to accomplish? The character might not be fully aware of his own motivation. A good motivation inspires your character to action so the GM can use it to involve you in events. The GM might also use the motivation to bring your character into contact and cooperation with the other player-characters. Beware of motivations that will make your character hard to play.

Like Wushu, we're connecting the motivation of the character as conceived with the character sheet. And just like there, this is a big flag to the GM and other people at the table about what you want to experience in terms of story. Things that appear in your motivation are clear indicators to everyone else of the sort of things that you want to play with.

The mechanical manipulation of motivation within the context of role-playing games is something that evolved from a simple notation like this and has seen some different manifestations, some of which are very directly game mechanical, in some very radical designs.

But that's another post.

For Arleen, let's give her a pretty straightforward motivation, "to make enough money to feel comfortable getting out of the business, settling down, and starting a family."

In the field of traditional literature that's a pretty tried-and-true, maybe even boring motivation – but for role-playing game character? How many RPG characters you know which want to settle down and start a family?

As some flags for the other people at the table, this is a pile of red meat. Anything that means that Arleen could make some money, she'll jump at. Anything that might keep her from getting out of the business or facilitate it, she'll jump at. Anything that might lead to her building a family – or threaten it, she'll jump at.

That's some big, juicy hooks.

Secret

Choose some secret, some hidden fact that few others, if any, know about you. Pick a dark secret, if you can, something you desperately want to keep hidden from others. Again, this secret can help you get involved in plots and intrigues.

Again, more big flags to wave in front of the other people at the table. Note how this is openly on the character sheet, not a secret to the other people at the table – it's just one more way to get involved for everyone.

I like big, juicy secrets, the kind that can lead to all sorts of terrible complications everywhere you go. Thinking about Arleen's flaw, let's go a little deeper.

"Consistently embezzles a little bit no matter where she's working."

How could that possibly go wrong?

Important Person

Choose one person who was important in your past, and decide how that person was important to you. It could be someone you know personally, or merely someone you admire, even a fictional character.

Just more flags.

The importance of this one is that it's, at heart, about connecting characters to one another. In later game designs that will be a more specified intent, often clearly requiring that you need to define your relationship to the character of someone else at the table. At this point, the text is taking a little bit of a copout, allowing for that important person to be "fictional."

With Arleen we don't have to hold back.

"Her sister, Jackie, who works in Al Amarja's Department of Civil Affairs, Capital Crimes Division – and who suspects that Arleen is involved with a very powerful criminal syndicate, which may be the only one on the island that she's never actually worked with."

Background & Equipment

Fill in all the details you want about your character’s background. List the possessions the character has and have some idea of the financial resources he will have. Choose items and finances appropriate to the character concept.

What, no crazy, long, detailed list of dear to pick through like the Sears catalog at Christmas? No detailed rules for figuring out how many gold pieces or fat US dollars are hanging out in your pocket at the beginning of the game?

Nope.

Basically, this can be summed up as "tell me more about your character. Give me a list of stuff that you care about and which other people can threaten. Drop more flags all over the table."

So let's do that:

"Arleen lives in a modest apartment in the fiscal center of Freedom City, in part because she has no particular extravagances and in part because she's socks away all of her extra cash just in case. She has a number of accounts all over the world, most of them containing just a little bit of money – most of which she is not supposed to have. She owns a beat up Harley motorcycle that she only gets to ride on the weekends and a yearly-renewed bus pass, good all over the island."

That's it! We are done. We have a fully developed character ready to go which is full of character hooks, plot hooks, and straight up shenanigans.

Let's put it all together in a single character sheet.

Arleen Spector, Freelance Combat Accountant

Combat Accountant – Covers advanced forensic accounting techniques including knowing how to tell if someone has cooked the books, tracing pseudonymous transfers through the blockchain, staying awake doing boring things for long hours, and effectively being able to engage in small arms combat while keeping your head down. (Really advanced cell phone with the case covered with pictures of dollar signs.) 4

Monkeyshines – Tomfoolery. Shenanigans. Pranks. If it involves fooling people for comedic value and possibly just a little bit of embarrassment, it's game on. Covers hiding in office furniture, concealing water balloons, stealthily placing whoopie cushions, and maintaining a deadpan expression. (A tattoo of party balloons and confetti on the inside of her left wrist.) 3

Long-Distance Runner – it's a long way to temporary, but Arleen can probably run the whole distance. Covers breath control, making sure she stays hydrated, finding quick places to go to the bathroom outside, truly terrifying endurance, and just absolutely, positively, will not stop – running. (Extremely well developed and shapely thighs.) 3

Disgruntled Associates – When engaging with people involved with and especially at the top of organizations with stuff to hide financially, there's a one in six chance that that person has had an unpleasant association with Arleen and is reluctant at best and adamant at worst that she not be involved. (Always seems to be eyeing the door when in corporate or criminal environments)

Hit Points -- "Just keeps ticking." 28

Experience Pool - 1 die

Motivation - "To make enough money to feel comfortable getting out of the business, settling down, and starting a family."

Secret - "Consistently embezzles a little bit no matter where she's working."

Important Person - "Her sister, Jackie, who works in Al Amarja's Department of Civil Affairs, Capital Crimes Division – and who suspects that Arleen is involved with a very powerful criminal syndicate, which may be the only one on the island that she's never actually worked with."

Background & Equipment - "Arleen lives in a modest apartment in the fiscal center of Freedom City, in part because she has no particular extravagances and in part because she's socks away all of her extra cash just in case. She has a number of accounts all over the world, most of them containing just a little bit of money – most of which she is not supposed to have. She owns a beat up Harley motorcycle that she only gets to ride on the weekends and a yearly-renewed bus pass, good all over the island."

And that's it for now!

Is this the kind of content that you enjoy? Would you like to see more step-by-step character generation, possibly for GM-less games, other games that I find interesting, or for FATAL which would require me to actively role for "anal circumference?" Let me know what you want to see more of, and if I feel vaguely motivated in that direction – that's what you'll see more of.

In the meantime, get out there, drop some flags on the table, and make a mess of things!

Congratulations @lextenebris! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPAnother enjoyable read :) Thanks for writing this.

Now I wish I was anywhere closer to you since you sound like a fun person to meet over a gaming table :)

Current plans put me in Toronto for Anime North this year, so if that's anywhere near your agenda, come on out. I might actually end up running some games this year.

I live in Israel and I don't think I'll be traveling to Canada this year. I'll remember if I happen to win the lottery :)

You can never tell. I've seen stranger things happen. [grin]

Excellent stuff.... as I'm coming to expect, coming from you.

I recall Over The Edge, from one con session many years ago about the (CENSORED) that (CENSORED) the (CEN- hey, how'd you learn about THAT?!?). It was entertaining, but the mechanics were in my then-opinion clunky and got in the way of the twisted setting's premise. Very similar to HOL (Human Occupied Landfill) or Hackmaster, the setting's glory is overwhelmed by the mechanics (which of course is kind of the point with the latter game)

Oh, and for the record, I'm a fan of Champions. While character progression is painful, it at least lets you do ANYthing, and provides a flexible backbone mechanic. So yes, I've got the thin blue CHAMPIONS! book up to the more recent versions capable of being used to hammer in nails. :)

Please note the kindness here - not a single character mentioned. You're welcome.