An in-depth review of the Mouse Guard tabletop RPG (first edition)

(This review is for the first edition of the game. There is currently a second edition which makes some minor updates to a few rules, but the main thrust of the game remains the same, so many aspects of this review still apply.)

Gritty, not grimy

Mouse Guard isn’t the place to find morally compromised anti-heroes who want to burn the world down before they burn out themselves. It also isn’t the place to find above-it-all superheroes who are guaranteed to save the day with style and panache. Mouse Guard is the place to find heroes, people who are doing their best to do a difficult yet important job. The people, in this case, are mice.

Mouse Guard has no fantastical elements beyond semi-anthropomorphized animals who have their own Medieval-level civilization. But once you step into that conceit, the natural world gives you all the larger-than-life drama you could ever need. When you’re the size of a mouse, a snake or an owl can be scarier than any dragon, and defeating them is just as noteworthy. The mouse civilization is always on the brink, with towns one winter, one flood, one drought, one war away from destruction. The Guard and the Guardmice are in a unique position, and their actions and their decisions can be the ones that make the difference between life or death, war or peace, unity or division, justice or corruption, progress or decay. What the characters do matters, not just to them but to everything around them. But it’s not handed to them on a silver platter: maintaining a functioning society in a hostile world isn’t cheap or easy, it takes real effort. And sometimes mice can’t rise to the level of heroism needed, and sometimes even heroes aren’t enough. Nature, both in the uncaring elements and in the needs and passions that burn in the heart of every mouse, pulls no punches. This is a gritty world, it may grind you down, but it’s not a grimy nihilistic world that tries to tell you that nothing is worth fighting for.

This biggest mechanical reinforcement of this thematic element, where characters are kept grounded in the reality of their world, is the Natural Order. Every type of animal in the Territories is rated by size and place in the food chain. Mice can use their weapons to fight and kill things within one rank of them, like other mice or the dreaded weasels. Animals within two ranks, like a beaver or an owl, can be captured, injured, or run off, but not killed by a mouse’s paw. The best that a patrol could hope for with a bigger animal is to merely run them off. If the mice want to have more impact on those animals, or engage with something truly enormous like a wolf or bear, individual mice (even mice with swords) aren’t enough, and they’ll need to raise an army and use the methods of war.

A Goldilocks-amount of setting information

The way Mouse Guard presents its setting is excellent. It provides evocative, concrete details without bogging the reader down with an encyclopedia’s worth of information. It communicates the spirit of the world and puts each GM in a good position to be able to fill in details that are consistent with the overarching ideas without much fear of running afoul of canon.

For example, in describing the towns and cities the book usually presents a few interesting geographic, political, or economic details with each one. Any of them can serve as a “nucleation site” around which ideas for a mission can crystallize. Need to build a scenario around a shipment or convoy of some type? Find a town with an interesting export and a reason why another another town might need it. Want to put the patrol in the middle of a political dispute? Find a town which has a system of government that’s conducive to the kind of dispute you want to explore. Want to feature of particular type of environment in the scenario? Find a likely place on the map and come up with a reason to send the patrol on a mission there.

The descriptions of the environments, weather, and creatures are similarly useful, and the beautiful art definitely helps you connect with them. In our normal lives it can be easy to gloss over woodland creatures or outdoors environments, but the way they’re presented in the book tends to fire the imagination, recasting the back yard as an exotic locale. The book provides enough detail so you can feel confident you’re using things correctly but leaves enough rough edges and empty space that you’re eager to start filling things in on your own. Things as simple as different tags that describe each creature’s Nature are a high-impact way of getting you excited to see that creature “on screen”.

The political tensions in the territories and the rich possibilities of the recent war with the weasels are also great story fodder. Nearly any way you cut across them can produce interesting stories. The tensions between political unity and independence and freedom and tyranny have several good hooks in the complicated relationship between Lockhaven and the outlying towns. The looming weasel threat provides great opportunities to explore the dangers of excessive militarism and the dangers of insufficient vigilance. The prospect of weasel spying provides opportunities to explore issues of trust and loyalty. Even the weasels themselves provide interesting story fodder, since they have an element of both the monstrous and the civilized: demonizing them or ignoring their nature can both be fraught paths.

I was unfamiliar with the Mouse Guard comics before I read the RPG, but was able to play in and run several satisfying campaigns. Now that I’ve had a little exposure to the comics I think those campaigns were pretty consistent with the comics in theme, tone, and focus. While I’m not enough of an expert on the comics to speak definitively, my perception is that the game did an excellent job capturing and communicating the spirit of the property; it’s not just a playground for people already in-the-know to regurgitate what they love at each other, it’s an expression of the ideas of the property in a different medium.

Skill System Matters

There are several elements in the Mouse Guard skill system that make it feel like it operates against a solid foundation rather than an elastic envelope around the players. This is good for the game design and also reinforces the thematic core of the game in which the mice are struggling to survive in a world that is, at best, indifferent to them.

The skills are generally well-defined with little overlap; it’s nearly always obvious which in-fiction actions correspond to which skills and vice versa (Scout is a bit of an exception, since it corresponds to a verb in plain English and the “skills as job titles” framework isn’t strong enough to reliably get people to think of Scout as a shorthand for “the skills that a sneaky scout-y-ahead-y person uses”). Since skill applicability is usually pretty obvious, the prospect of trying to “fast talk” the GM into letting you roll a skill you’re better with than the truly applicable skill is a steeper road than in some other games. The requirements of the advancement system, where you need both passes and fails on a skill to advance it, further undercut the temptation to weasel around the skill system. And the mission creation and twist guidelines will generally make the full cross-section of skills relevant over the course of a campaign. Your skills matter: you’re good at what you’re good at and bad at what you’re bad at, and it all impacts your experience of play. Since the world reacts across the entire spectrum, nobody is quietly papering over your deficiencies or undercutting your excellence. The world isn’t out to puff up your ego or minimize you, it’s there to let you experience your mouse as they are.

From the GM side, the “skill factors” system of calculating obstacles does an excellent job of keeping the system grounded in the fictional reality. When other games ask GMs to make unconstrained judgment calls about target numbers it can be very easy for their attention to drift to the PC’s skills as an anchor point, which makes TN setting an exercise in the GM deciding whether they’d prefer to see success or failure, dynamically scaling the world to provide a specific experience for the player. But when the hand of the GM becomes so important to the resolution system the player’s contributions during chargen and advancement (which are reflected in their skill ratings) necessarily get crowded out. By contrast, the skill factor system makes it easy for the GM to call for obstacles exactly as hard as they ought to be, no more and no less, and if the mice triumph the GM can cheer along with the players and if they fail the GM can commiserate. In looser systems it can be easy to put your thumb on the scales, either intentionally or unintentionally, but when there are such crisp procedures for interpreting the fiction it’s easier to keep your hands off, which lets you gain a truer appreciation for something’s actual weight.

The twist/condition system also does a good job of making failure meaningful without it being catastrophic. Rather than having to construct arbitrary “branch points” into a mission, the twist/condition system allows the players to experience all of the prepped content while also not having their successes and failures feel purely cosmetic. The mechanical and fictional downsides of the conditions are important (although perhaps a little too weighty when it comes to Sick or Injured) and twists add more challenges to the mission, which means they’ll be at risk for more downsides from more rolls (and upsides too, of course, like more opportunities to collect the passes and fails that lead to skill advancement).

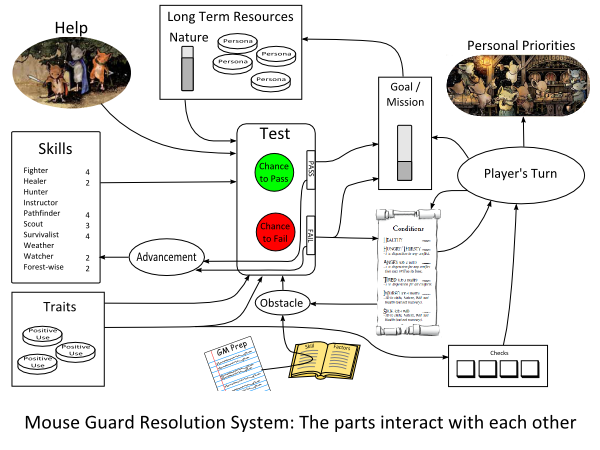

The parts all work together

Mouse Guard has several mechanical subsystems that work at different scales, and many of them are tied in to each other so that everything feels consequential, meaningful, and integrated into a greater whole. The interrelationships between the different parts can be complicated, so I created a diagram to show it in a visual way:

Each session of play consists of learning about the mission, a GM’s Turn, and a Players’ Turn. During those turns, the core of the resolution system is rolling dice to see whether you pass or fail a test: a player roll a pool of six-sided dice, each one that comes up as 4, 5, or 6 is a “success”, and if the number of successes is greater than or equal to the Obstacle rating of the test they Pass, otherwise they Fail.

Passing means that the character succeeds at what they were doing, which generally corresponds to making progress towards completing the mission in the GM’s Turn. If the player fails the test the GM has two options: they can insert a twist, which is a new problem or complication that the patrol will need to deal with before moving forward with the mission, or they can allow the task to succeed but have the character suffer a Condition, such as Angry or Injured. A Condition generally makes it harder to succeed at conflicts or tests, and getting rid of them usually requires mechanically scarce resources, such as using an action in the Players’ Turn to attempt to remove it.

For each test the GM sets the obstacle based on which skill is being used and what “skill factors” apply according to the fictional details of the problem (the game also has conflicts and opposed rolls, but they’re conceptually similar so I’ll just talk about simple tests for this analysis). A mouse can have a variety of Conditions, like Injured or Sick, which may also affect the Obstacle. Once the player knows the obstacle, they start building a pool of dice based on their skill rating. Additionally, if they have a special skill called a “wise” that applies to the situation they can take a bonus die for that (for example, Forest-wise would give you a bonus for a Pathfinder role to find your way through forest terrain). The player making the roll can also ask for help from each other player, and if they can describe how their character helps with one of their skills they can give one helping die, but that also exposes that character to some risk if the roll fails.

Players also have some spendable resources they can use to increase their odds of success. They can spend Persona points to give themselves a bonus die. They can also spend a Persona point to “tap their Nature”, which gives as many bonus dice as the character’s current Nature rating, but at the cost of “taxing” their Nature, which essentially reduces this stat by one for the length of a campaign. Players can earn Persona points during the end-of-session reward procedures (one of the ways to get a Persona point is to accomplish a Goal that the player decides on before the mission begins).

Characters also usually have several traits. A player can use a trait positively for a bonus die if the trait seems relevant to the action the character is taking, but most traits can only be used positively once per session. Another important aspect of using traits is using them negatively. If a downside of a trait seems like it could be relevant to the situation, the player can choose to take a penalty to their roll. By doing this they earn a Check, which gives them an opportunity to make more rolls during the Players’ Turn. The Players’ Turn is when characters can pursue their personal priorities, such as removing troublesome conditions, trying to accomplish things that weren’t done during the GM’s turn, doing things for their friends and acquaintances, or practicing skills that they want to get better at. Without any checks players can only make a single roll during the Players’ Turn, so deciding whether and when to use traits negatively can have a big of impact on what a character is able to accomplish during a session.

While it may initially look like a quirky afterthought, the negative trait / Check mechanic is the primary connection between the events of the Players’ Turn and the GM’s Turn. Players need to get Checks, but they also need to succeed enough to accomplish their mission so that they can use the Players’ Turn pursuing their own priorities rather than fixing mistakes from the GM’s Turn (if that’s even possible). This inserts an element of resource management and risk/reward balancing on each roll during the GM’s turn. Each decision (such as whether or not to ask for help, or whether or not to showcase a facet of a mouse’s character that’s represented by a Trait) has mechanical consequences. These consequences make the roleplaying choices around each die roll feel weighty, but since there are pros and cons for each option you don’t feel like your decisions are being dictated by the mechanics, you can make your own choices, and those choices will have consequences.

Getting Caught in the Gears

While there are many game design advantages in having a complex game with many meaningful interactions between the parts, there’s a flip-side to that coin: Mouse Guard is not very forgiving for people who don’t know how to play it. Consider this scenario:

An enthusiastic new player with little rules-mastery and not-so-great math skills sits down to play. The first test in a mission has a very high Obstacle. The new player, wanting to succeed, goes “all in” to try to pass the test: they use one of their one-use traits, and they spend their only Persona point on a bonus die (sidestepping the “Tap your Nature” subsystem since those rules seem complicated to them). Unfortunately, even with these bonuses, their die pool still provides a small chance of success against the particular Obstacle they’re facing. Even more unfortunately they don’t have a good feel for how to judge whether success or failure is likely based on how many dice they’re rolling, but they’re confident that they’re giving it all they’ve got so their hopes are high. They roll the dice and get a Fail result. The contrast between their hoped-for triumph and their actual failure makes it hit particularly hard. Now, saddled with a Condition or some new twist they have to deal with, they feel like they’re in a hole and they need to climb their way out. Unfortunately, they’ve just used up a lot of their resources, so even though they’re desperate to succeed on their next rolls they’re less able to translate that desire into reality. Trying to avoid digging themselves deeper they avoid using their traits negatively on their other rolls, so they earn no Checks for the Players’ Turn. After feeling beaten up and ground down in the GM’s Turn they may not even have enough rolls to undo all the damage. And then they’ll have the opportunity to go through the end-of-session procedures and reflect on how badly they sucked.

While that scenario isn’t guaranteed to happen, I don’t think it’s uncommon either. These sorts of problems are exacerbated by the fact that many gamers have habits or intuitions built up by playing other games that make scenarios like that more likely. For example, some games train players to believe they don’t need to invest any effort into understanding the rules since the GM will “handle that”. Some gaming philosophies even elevate avoiding mechanics knowledge to a virtue, believing that asking players to think about mechanics is a threat to immersion. Many games with “spend points to get a bonus” mechanics tend to result in the die rolls become mere formalities on the way to succeeding at the roll, so the more tightly tuned mechanisms in Mouse Guard can end up defying those expectations. Even the notion of the GM’s Turn/Players’ Turn framework is foreign to many gamers, so there is a tendency to treat it as an “advanced” feature they’ll attempt to understand only after they’ve mastered the “basics”, which can leave them lost at sea since managing your resources and the Check economy is one of the main mechanical throughlines in the game. While it’s unreasonable to expect that any game can account for incompatible ideas imported from other games, the reality is that certain common styles of RPG play tend to be especially incompatible with Mouse Guard. In my experience it usually takes about three sessions for the system to “click” for people.

Speaking from personal experience, I dislike trying to teach people how to play this game while I’m sitting in the GM’s seat. A big part of what makes GMing this game fun is seeing how players will react to the situations I’ve prepped. Teaching the players how to play in Mouse Guard isn’t just teaching them how to read notation or properly interpret a table, it involves guiding them through how to make decisions, but when I do that I start to feel a sense of ownership in what decisions get made, which starts to veer into Czege-Principle-violation territory (the Czege principle: "creating your own adversity and its resolution is boring").

Mouse Guard is a great game, but it needs to be played on its own terms, you can’t just plug in ideas or behaviors from other RPGs and expect that they’ll give you the same results here. And if you do do that, this game won’t feel great to play.

What did you do during the war?

The recent war with the weasels looms large over the setting in Mouse Guard. It’s mentioned in the backstory of most of the pre-gen characters, it’s a common source of tension in the territories, and it’s a significant event in the Guard’s history. In the otherwise satisfying character generation system I found the lack of any impact from the war to be curious. This is especially odd since it’s difficult to acquire the Militarist skill in any way, even though you’d think that would be something a high-ranking Patrol Guard or Patrol Leader could have picked up during the war. The conflict subsystem carves out War as a unique attention-worthy thing, but it’s hard to build a character that’s good at it, even though you’d think there ought to be mice like that serving in the Guard given the history described in the book.

It’s a trap trait!

When using traits positively you can only use level 1 or level 3 traits once per session, but level 2 traits add a bonus die to every roll whenever the trait applies. The choice to use a level 1 or level 3 trait involves a mechanical tradeoff: do I want the bonus on this roll, or do I want to save it for later? Since there are pros and cons, on each roll you can usually make a reasonable argument for or against wanting to use it so it’s easy to accept that there are situations where the trait doesn’t apply. With a level 2 trait there’s no reason not to use it if you can, which creates a mechanical incentive for motivated perception: you’re tempted to justify the relevance of the trait even if it might seem tenuous from another POV. The “never runs out” feature of using a level 2 trait positively makes it seem awfully tempting to many people, but when you have it on your character sheet it can create uncomfortable tension when you feel dueling obligations between getting the most dice you can and playing the trait mechanics with integrity.

One of the ways to get level 2 traits is to double-up during character creation. This also has the result of leaving a character with fewer traits to work with when angling for negative uses/checks during the GM’s turn. Characters who double-up on traits during chargen will be more one-note and less satisfying to play, but the choices that lead to that result are tied to the highly tempting mechanical incentive of the level 2 trait.

The end-of-session procedures

At the end of each session of Mouse Guard you go around the table and each player reports their character’s Belief, Instinct, and Goal, and then, while thinking back about the session, the group decides whether the character acted in line with that Belief (or dramatically opposed it), acted on their Instinct, and accomplished their Goal. This is an excellent procedure that accomplishes several things at once. First, it provides a mechanical incentive, making it easier to embrace the idea that we should care about our Beliefs, Goals, and Instincts while we play. Second, it’s a good wind-down from play, helping you savor the events of the session but also providing an unambiguous stopping point. Third, having the player take a bigger-picture retrospective look at the actions they took while making in-the-moment decisions is a good way to encourage dramatic engagement: maybe the character has changed and no longer holds the Belief they professed to hold, maybe seeing examples of the Belief in action underscores how important it is, maybe you didn’t act in accord with your belief this session but it’s the exception that proves the rule that this Belief really is central to the character, maybe you acted in accord with the Belief but seeing the consequences of those actions give you second thoughts about whether you ought to continue endorsing it. Looking at events from multiple perspectives almost always produces a richer experience, and this procedure provides a good “excuse” to do that for something as seemingly frivolous as the events of a roleplaying game. When I’m GMing the game I always love it when I get to say “So, did you follow your Belief this session?” and a player holds their own character’s feet to the fire to see if they really lived up to their ideals.

In addition to the per-character awards, you need to name one player the MVP (most important contribution to the events of the fiction) and one the Workhorse (most consistent contribution to the events of the fiction) for the session. This also serves a somewhat retrospective purpose, but it can sometimes feel a bit uncomfortable, as many people don’t like to play favorites with their friends. There is often an impulse to be “fair” with these designations, which can cause tension if your egalitarian and meritocratic intuitions don’t both point in the same direction.

Lastly, you need to award the Embodiment, which is more or less a “good roleplaying award”. Sometimes this is really easy, such as when someone busts out a fun accent or vivid characterization. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable, such as when the same person’s vivid characterization has been outshining quieter players session after session. Personally I hate this award, I hate feeling judgmental about other people’s “performance”, and I’m so prickly about others judging me that unless people exactly thread the needle I’ll frequently feel either overpraised or underappreciated. I’d much rather not end a session on this weird note of social discomfort.

No Fate but what we make More Fate than we know what to do with

The end-of-session rewards procedures give out two kinds of points, Persona and Fate. Persona is very useful and can be used to get bonus dice on rolls, especially when you use the Tap Your Nature mechanic to get multiple bonus dice in exchange for a long-term drain on one of your stats. Fate, on the other hand, is very situational: it can be used to “explode” the 6’s on a die roll so you get to roll an extra die for each 6 that came up. In practice it’s relatively rare to get into a situation in which exploding the 6’s will make a difference, since it only seems worthwhile in the case where the gap between your current number of successes and the obstacle is small relative to the number of new dice you’d get to roll. (It tends to make more sense in conflicts, where the margin of success frequently matters). Since the are lots of ways to get Fate but relatively little reason to spend it, people tend to accumulate a lot of it, so there probably aren’t many incentive effects to gain more, and the decision to use it or not doesn’t tend to have a lot of now vs. later tradeoffs like you get for truly scarce resources like Persona.

The “visual language” of the book

The Mouse Guard book is physically beautiful to look at. The art is excellent and evocative, and the visual design of the pages is eye-pleasing. I’m less sanguine about the functionality of the text. In interviews, Luke Crane would tell this really compelling story: In laying out Mouse Guard he used a “visual language” for how to format the text so that people would be able to quickly and instinctively connect ideas using visual cues like the typeface and color. That sounds really good! In practice I don’t think it works. When I run into some oddly formatted text while reading the rules my reaction is “I know that’s code for something, but I’ll be damned if I can remember what.”

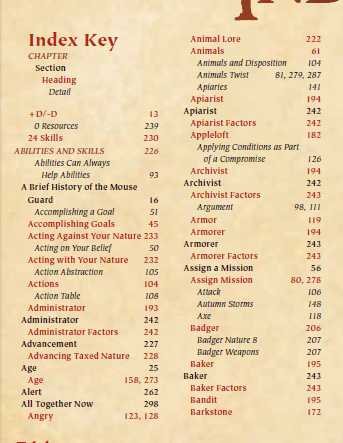

The “visual language” problems are most apparent in the index. As you can see in this image (if you look closely) there’s a “key” to how the index is meant to be read, with various typefaces, colors, and indentation telling you whether something is a chapter, section, heading, or detail. Alternatively, if you’re a human who’s been reading english-language books for a while, you’ll interpret indentation is an indication of a subtopic. This instinct is immediately reinforced by the first entry, where Abilities Can Always Help Abilities looks like a subtopic of Abilities and Skills. However, A Brief History of the Mouse Guard isn’t really meant to be a subtopic of Abilities and Skills, and Accomplishing a Goal is definitely not a subtopic of A Brief History of the Mouse Guard. The apiary-related entries in the second column are also a great illustration of how the indentation strategy is strongly fighting against the actual “flat” structure this index has. The “visual language” of this index wants to use indentation as a per-item piece of information, but it’s nearly impossible to override our instincts to use indentation as a cue to how to interpret chunks of text. As a result people frequently find themselves unable to locate things in the index because they subconsciously decide to skip “subsections” when the “main topic” isn’t relevant to what they’re trying to look up. If you ignore the formatting the index is actually pretty good, but it takes a lot of work to ignore the formatting.

Player Created Conflict Goals

One of my mental stumbling blocks with Mouse Guard‘s game design is in the conflict system, specifically the need for players to declare their own goals for the conflict. The mechanical bits of the conflict are fun and engaging, but the prospect that a GM won’t be able to guarantee what a conflict is about can make it a bit tough to build a conflict into the GM’s Turn mission structure. In reality I know I can generally manipulate the situation sufficiently to have a good guess about what goals players will take, but I feel scummy when I do that since the rules specifically carve that out as a player decision. For example, in one session I wanted to create an opportunity to showcase the War conflict, especially since one of the characters had a Militarist skill that wasn’t seeing much play, so I prepped a situation in which the mouse patrol stumbled across a weasel army bearing down on a village of bedraggled weasel separatists who were trying to build a life outside of weasel tyranny. The players, as I expected they would, sprang into action organizing the weasel refugees leading them in the defense of their village. Instead of just saying flat out “we’re going to have a War conflict about defending the village” I felt compelled to play cutesy magician games waiting for them to say the magic words that would justify doing the conflict I had already prepared for. There are other missions where I more or less arbitrarily declared that we’d be doing a Journey conflict, in effect telling them what their goal should be.

Officially, a conflict’s goals are supposed to “include a statement about your character, and action and a target” a la “kill this snake so that Kenzie and Saxon are safe”. In my experience the “do ______ so that _______” pattern quickly drifts into a more straightforward expression of intent, which makes the conflict system look a lot like negotiated double-ended stakes as you see in some other games. Even if you are scrupulous about the type of goals you take it can be a bit weird. I recall one conflict where the patrol was trying to drive off a bullfrog that had built a lair near a path between towns (I introduced the frog as a twist on a failed Pathfinder test). The frog was aggressively territorial, so we did a Fight Animal conflict where the players’ goal was something like “drive the frog from its lair so that the path is free”. Once we resolved the conflict and it was time to compromise most of the players were completely happy to jettison the “mere color” of dealing with the frog’s long-term presence near the path in order to avoid consequences related to the physical fight which would have been mechanically represented. While I theoretically could have reincorporated the frog into later missions (he would have been an impediment to trade), patrols tend to travel widely so it would have been a long time before those consequences ever showed up “on screen”. The players were excited about having a combat with the frog, the pro-forma requirement that they have an appropriately phrased goal didn’t get them to emotionally invest in that goal.

The expectation of a compromise result also tends to incentivize players to adopt classic bargaining strategies like asking for more than you really want so that you have “someplace to go” in the compromise (as I GM I tend to feel an obligation to be and honest broker and set the goals for what the NPCs or animals would “really want” out of the situation). The artificiality of claiming to be pushing for a goal you’re not actually invested in tends to undercut some of the drama of a conflict, in my opinion. The potential interesting results that could arise from compromises are also undercut when they’re gamed around before you even start the conflict.

The GM’s mission-preparation procedures

The GM Prep procedures are excellent: they’re fun to do and cause you to create content that contributes to a fun experience during the sessions with little or no wasted effort. A key element of the mission creation procedures is that the Beliefs, Instincts, relationships, and unusual skills from the players’ character sheets are fantastic flags for creating rich and engaging situations. This combines in a very satisfying way with procedures that tell you how much “content” is the right amount to create for a given mission: the rules tell you to pick two things from the list of: weather, wilderness, animals, and mice, and build your mission around them (keeping the other two as potential twists). With a framework for the “form” of the mission in place, you can express your constraint-guided creativity as you mix and match elements, creating opportunities to interrogate the flags on the character sheets. You can explore the nuances of the beliefs, play them off against each other, pit relationships against instincts. It all forms a rich tapestry that becomes the foundation for each session of play.

For example, in one session I had a patrol with one mouse whose belief was “The Guard looks after its own”, and who had a rival that had previously been a patrol-mate in a patrol led by the PC’s now-retired mentor. Another member of the patrol had the belief “The Guard must do the most good for the most mice”. I thought that it would be interesting to explore how the plight of a retired guardmouse would intersect with the “looks after its own” belief, which could play off the more utilitarian belief of the other PC. I created a situation in which the retired mentor wasn’t being particularly well cared for by the guard: her pension wasn’t enough and she was making ends meet by doing difficult physical labor (does the Guard really take care of its own?). The PC’s rival learned of this while on a mission to guide a convoy of food supplies to a starving town. She decided that she would stop the convoy in the wilderness, and once the starving town was desparate enough they’d be willing to pay extra for the food, which would give her the funds to pay for the mentor to retire in comfort (is it OK to risk the welfare of many mice for the good of one?). The guard leadership only knows that the convoy they expected to solve the starvation problem hasn’t gotten through yet, and the PCs are assigned the mission to resolve the situation. They go to the convoy’s starting location and find out about what’s going on with the mentor and the rival’s involvement (a mouse problem) and then need to track down the convoy along the route it would have taken (a wilderness problem) at which point they’ll have all of the elements of the ethical thicket and will need to decide how they want to resolve things.

In another mission, I decided to explore a political situation by playing the PCs’ enemies against each other. One was a government official in a character’s home town, and another was an influential civilian consultant on military and defense issues (who had been quietly exacerbating tensions with the weasels so that he’d have more business). The mission begins as a labor dispute: a guild of stonemasons has been hired by a town to build some fortifications but the town isn’t paying them. The town-government official in charge of the contract is one PC’s enemy, but the reason he won’t pay is because he’s already spent all the money in his budget to pay the other PC’s enemy to create the high-quality plans for the fortifications. There are more mice demanding payment than the current budget allows for (a mouse problem) and the stonemasons are stuck without payment or a way to get back to their home town and the military consultant has already left town (wilderness problems). Who gets stiffed when there’s not enough money to go around? The laborers? The hated expert? Maybe the taxpayers? What does it feel like to try to resolve a problem that someone you dislike is currently embroiled in?

In another mission, one PC had a belief along the lines of “The Mouse Guard takes care of its own”, which I thought had the interesting nuance of being ambiguous between whether that meant “protects its own” or “polices its own”. Another PC had a belief like “A guardmouse never gives up, no matter what”. I thought it would be interesting to see how they’d deal with a situation in which a guardmouse had given up unnecessarily. I created a situation in which a bird was using its mimicry abilities to make hawk cries (an animal problem), thus scaring mice away from grain shipments they were delivering, including a small guard patrol that was supposed to be escorting one of them (a mouse problem). Once the patrol resolved the bird situation, how would they react to the patrol that had failed to address it due to its leader’s cowardice?

The mission creation guidelines do an excellent job of creating RPG-session-sized chunks of content. Knowing that the Player’s Turn will provide lots of opportunity for player-directed activity frees the GM to be comfortable creating a roller-coaster (i.e. a fun railroad) through the adventure-y parts as the mission, but doing this sort of prep also encourages you to create a hands-off playground for meaningful choices when the patrol is confronted by the interesting situation. Prepping a mission in Mouse Guard is a fun, game-like creative challenge on its own (i.e. filling in the “slots” of what makes for a properly-formed mission by using the flags from the character sheets and the setting details is an enjoyable creative puzzle), and then this preparation helps ground the GM in the proper posture so they can be a combination of impartial referee, proud craftsman showing off the result of their creative work, and enthusiastic audience who’s eager to see what the players/characters will do once the situation is introduced. Plus, since the mission was inspired by flags from the character sheets, it’s almost guaranteed to seem engaging to the players and is likely to tie into Belief-relevant actions, which helps the end-of-session reward mechanics work.

I think the mission creation procedures in Mouse Guard are a brilliant piece of game design. They’re fun to do. They encourage the creation of morally or ethically interesting situations without ramming head-on into hot-button issues like in Dogs in the Vineyard. They lead to fun and engaging play during the sessions. They’re meaningful without dominating play. They encourage the creation of exactly the right amount of content, with not much throw-away work (I also think it’s wise to prep twists, which don’t always come into play, but are often portable to future sessions if you don’t use them). They help put you in the proper frame of mind to have the most fun during a session. They’re great.

Conclusion

Mouse Guard is a great game, but because most of it is so good there are a few sour notes that stand out due to the contrast. Don't let that shade your reading of this review, I’ve had a lot of fun playing the game and GMing the game and I recommend it (as long as you're willing to put in the time and effort). It’s also a useful and important game for RPG design enthusiasts to study.

Note: As I said at the beginning, this review is of the first edition of the game. There's currently a second edition, which I haven't read or played myself. As I understand things, it makes several minor mechanical changes such as to the way traits and wises work. However, I have heard reports that there are some unfortunate editing errors (especially related to the examples, which apparently weren't all updated to track the new mechanics) which serve as a minor impediment.

this is really cool I play mouse guard 2e with my friends once a week, We're mouseguard veteran by now. Now we're trying our luck with MG father, Burning Wheel, with good results. Visit my profile, I'm posting lots of maps, @derekvonzarovich I write all the stuff at Elven Tower.

Awesome post. if you help me then I will help you a lot

follow me @maruf121. thanks and don't forget tip. also i have a youtube channel plz go

and subscribe-https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCdLTzGuwJd2hY5mLEh1tk5A/featured

@danmaruschak This is supercool! Thanks!

Congratulations @danmaruschak! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP