Flood Aid in Louisiana: What Role Should the Government Play?

The United States government has bailed out big banks and car manufacturers. Should it bail out disaster victims also? That is the focus of a major debate that is brewing in Washington. After floods in the state of Louisiana caused catastrophic damage, the issue is not just relief assistance (as it was in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005). The greater problem now is that many of the people who lost their homes in this flood were outside the flood zone and had no insurance.

What is the role of government here? When a flood destroys peoples’ homes outside the official flood zone, and half of them may have had no flood insurance, should the government step in?

This raises questions about the fundamental role of government. Should it be taxing people in order to provide comprehensive disaster assistance, and if so, to what extent? Some of us are rather suspicious about big government and would prefer it to be smaller, taxing people less. But it’s also hard to deny that if there’s one time when we need society to band together and help out, it’s after a major disaster has struck. Perhaps government is society’s way of providing that mutual benefit to one another.

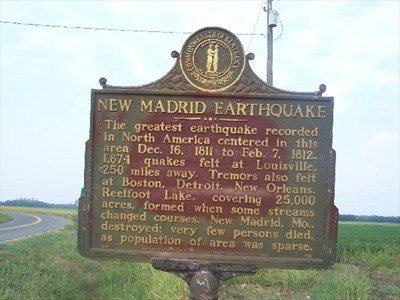

Before the 1811-12 New Madrid Quake Along the Mississippi River, People Were on Their Own. No One Expected the Government to Rescue Them.

When the U.S. government was created, there was no expectation that the federal government would help with disaster assistance. If there was a flood or a drought, that was hard luck. The situation then was much different from the expectation in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans. Government at all levels (but particularly the federal government) was criticized for an inadequate response. Katrina produced a terrible human disaster, and yet it also showed how much society has come to depend on the government response.

Originally, the federal government was not meant to take such an active role.

On December 16, 1811, a powerful earthquake struck along the Mississippi River, centered at New Madrid in the Missouri Territory. It measured at least 6.7 on the Richter scale (perhaps as high as 8.6) and was followed in the next few months by additional 8.4 and 8.7 earthquakes plus more than 1,800 tremors over that period. It was the most widespread disaster in American history, impacting much of the middle of the continent. Thankfully, there weren’t as many people living in the region then, but it certainly caused a broad swath of devastation for those who did.

Can you guess what kind of disaster relief the government provided to the victims of the New Madrid quake? None.

That’s right, none. These people lived on what was then a frontier. After the disaster, churches filled with “earthquake Christians”, but no one complained that the feds never arrived. Until that point in U.S. history, there had never been any expectation that the federal government’s role should include disaster relief.

In March 1812, an earthquake struck Caracas, Venezuela and caused great damage there. As a friendly (but mostly unprecedented) gesture, the U.S. Congress decided to send $50,000 in earthquake relief to Venezuela. A few months later, Missouri’s Congressional delegation began to wonder why a foreign country was getting disaster assistance after an earthquake, while no such assistance had been given to domestic earthquake victims.

It took two years, until January 1814, for the Missouri delegation to petition the U.S. Congress for federal disaster aid. When it came, Congress simply allowed landowners in the affected area to exchange their land titles for titles to new tracts of public land. And because the news moved slowly, speculators and con artists bought up most of these claims before anyone knew what was happening.

But that was the beginning of federal disaster assistance in the United States. And since then, it’s been expected that the federal government would step in after a major disaster. These expectations ramped up higher with the Great Depression and New Deal programs. Since then, the federal government has participated more actively in both the welfare state and in disaster relief.

Hurricane Katrina

Then came Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the costliest disaster in U.S. history. The federal government, along with all levels of state and local agencies, were widely criticized afterwards for their anemic and mismanaged response to this crisis. All told, more than 1,200 people lost their lives in the storm and flooding that year, while the total price tag from the damage reached $108 billion.

What was the expectation then? “Government, where the hell is the government, why aren’t they coming to rescue us? We’ve been waiting three days for buses, fresh water, and medical supplies. This is unconscionable.”

And the suffering was unconscionable. No country as rich as the United States should allow that kind of human suffering on a mass scale. Helping is the right thing to do. But in the past, it wasn’t the federal government’s role to be responsible for everything. The government’s response to Katrina was only “unconscionable” when viewed through the lens of modern expectations of the role of government.

The 2016 Floods and the Insurance Bailout

It isn’t easy living in the path of powerful storms and in the delta of one of the world’s largest river systems. This year, Louisiana was struck again. The main flood damage occurred a little further north from where Katrina hit hardest.

In August 2016, there was significant and prolonged rainfall in the southern part of the state. An unnamed storm dropped three times as much water on Louisiana as it had received from Hurricane Katrina. The amount of rain that fell could have filled Lake Pontchartrain three times; it was that much water.

Understandably, 7.1 trillion gallons of rainfall caused some rivers to overflow. 146,000 homes were damaged or destroyed. To date, more than 100,000 individuals and households have registered for assistance from the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and that agency has approved assistance that totals $132 million.

Fast disaster aid was the Katrina issue. Katrina made that expectation clear and the government has done a better job delivering relief. It was not a major issue this time.

But this flooding is leaving the taxpayers with a far bigger issue on their hands. At $3 billion in size, that issue will grow much larger soon.

Many of the victims of this flood lived outside the official flood zone. Some of them were told by the government (at some level) that they did not need flood insurance. And so flood insurance does not cover the loss of their houses, their belongings, their lives.

The government’s National Flood Insurance Program has $ 3 billion that Congress has appropriated. That includes its $1.7 billion reserve fund. That should be enough to cover those who are insured in this flood. If they need more, that program can go to Congress and request more money.

What about those who had no such insurance? What about the ones who lived outside the official flood zone and were told they didn’t need insurance? They lost their homes, too.

Currently, they are eligible to apply for FEMA grants of up to $33,000. That doesn’t cover much for those who lost homes.

The buzz is growing in Washington over the possibility of a much larger bailout.

After Hurricane Katrina, the U.S. government coughed up another $13.4 billion aid package. Could there be another bailout on the horizon for these flood victims? Politically, it's more difficult this time, but this could happen.

We must help those who need it most. And yet, this growing debate raises serious questions about government’s role in our lives. Should we expect the federal government to bail out disaster victims for every hurricane, tornado, and earthquake? It is extremely costly. And one can argue that people should have responsibility of their own when they choose to live in an area that is prone to disasters.

But when someone has lost everything they own, it’s understandable that we have a hard time drawing that line. I’d rather we have a discussion about it as a society at a time when we’re not forced into this kind of decision. We need to decide how society can best band together and help others at a time of crisis. I’m not sure government and its taxpayer billions are the best or only solution.

-Peace, Richard, @steemship

Sources:

Disaster Relief, then and now: https://fee.org/articles/disaster-relief-then-and-now/

LA Flood Insurance: http://money.cnn.com/2016/08/18/pf/louisiana-flood-insurance/

Uninsured Victims: https://weather.com/news/news/uninsured-flood-victims-financial-loss

$3 Billion Insurance Coverage: http://www.bna.com/louisiana-flood-insurance-n73014446712/

Wikipedia Katrina: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurricane_Katrina

Smithsonian Great Earthquake of 1811: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-great-midwest-earthquake-of-1811-46342/?no-ist

Coming Bailout of Flood Victims? http://www.theadvocate.com/louisiana_flood_2016/article_dbd9423a-6bca-11e6-9490-1721745d0c8b.html

Reasonable questions. However do we want something as untrustworthy as government taking over the role a private enterprise could do more efficiently?

Well, isn't the private enterprise of homeowner's insurance supposed to do it? Except it doesn't, because if you don't get all the rights part on your policy, you can be denied coverage. And just where can someone live now where some natural disaster or another doesn't strike? If you look at the role of climate change, maybe the manufacturers who polluted the world should be billed for these increasingly severe weather occurrences. That environmental cost never seems to get paid.

And most of the time insurance companies will also find a way to avoid claims.

Thanks for sharing this material, I like what you posted. Thank you so much

Remember that early in the morning I saw the news on August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast of the United States. The storm made landfall, it had a Category 3 rating. The storm itself did a great deal of damage, but its aftermath was catastrophic.

Hurricane Katrina definitely caused catastrophic damage.

I'd like to think any modern government would help. I mean, they rort so much money for themselves, they should help...

But as a tax payer I'd question it. Even resent it.

However if it was me or my family I'd expect the government to help. I mean it's not 1812.

Good post btw

Fuck Apathy

I moved out of New Orleans in April of 2005. The guy who trained me in my first job down there died in Katrina. These are certainly good ideas to think about ahead of time, before something else happens. Thanks!