Shize? I Should Shee!

To repeat myself for the fourth time, this paragraph—which runs from 005.27 to 005.40 in my preferred text, The Restored Finnegans Wake—has to be read in conjunction with the preceding three. Taken together, these four paragraphs paint the popular Irish-American ballad Finnegan’s Wake in the colours of a Viconian Cycle. According to Giambattista Vico’s philosophy of history, human civilization passes through three phases before collapsing into the chaos of uncivilization. But this chaos flows back into the first phase, and the Viconian cycle begins anew:

- Theocratic Phase: The Age of Gods

- Aristocratic Phase: The Age of Heroes

- Democratic Phase: The Age of Men

- Ricorso: Collapse into chaos and subsequent resurgence

This paragraph, then, represents Vico’s collapse and ricorso, which Joyce transformed into a fourth age in its own right, albeit a minor one compared to the other three. In Finnegans Wake, the first three ages comprise eight, four and four chapters respectively, while the ricorso comprises only a single chapter.

Vico devotes the concluding book of The New Science to what he calls the Ricorso delle Cose Umane nel Risurgere che Fanno le Nazioni, or Recurrence of Human Things in the Resurgence of the Nations. In this book, Vico demonstrates how the re-emergence of civilization after the Dark Ages echoed the emergence of the first civilizations after the Universal Flood.

1046 In countless passages scattered throughout this work and dealing with countless subjects, we have observed the marvelous correspondence between the first and the returned barbarian times. From these passages we can easily understand the recurrence of human things in the resurgence of the nations. For greater confirmation, however, we wish in this last book to give a special place to this argument. Thus we shall bring more light to bear on the period of the second barbarism, which has remained more obscure than that of the first, though Varro, most learned student of the earliest antiquities, in his chronological division called this the “obscure” time. And we shall also show how the Best and Greatest God has made the counsels of his providence, by which he has guided the human things of all nations, serve the ineffable decrees of his grace. (Vico §§1046)

Note that Vico equates these barbarian times not with Joyce’s Fourth Age, but with the First Age, the Age of Gods. Vico did not recognize a fourth age: for him, what Joyce treated as an Age of Chaos and Uncivilization was merely a brief transition from one cycle to the next.

First Draft Version

Joyce’s first draft of this paragraph comprises a brief but fairly transparent depiction of Tim Finnegan’s actual wake:

Size! I should say! MacCool, macool, why did ye die! Sore They sighed at Finn[’s] wake. There was plumbs and grooms and sheriffs and zith[erers] & raiders and cittamen too. ’Twas he was the dacent gaylabouring youth! Arrah where in this world would you hear such a din again it? The owl hangsigns & the thirsty fidelios! They laid him low along his bed. With abuckalyps of finisky at his feet & a barrowload of guinesis at his head. To the total of the fluid & the twaddle of the

fuddled, O. (Hayman 47)

Note the reference to Auld Lang Syne [owl hangsigns], a song that celebrates the renewal of the old. In the final draft, this has been replaced with an allusion to the De Profundis (Psalm 129, Out of the Depths). The thirsty fidelios suggest Adeste Fideles, another song associated with Yuletide and the New Year.

Finnegans Wake has several narrative planes. There is the nocturnal plane, in which the events of the book cover just eight hours between 11:32 pm on Saturday 12 April 1924 and the following morning. There is also, I believe, a diurnal level, which begins at 11:32 am on Friday 21 March 1884 and it ends at 11:32 am on Saturday 22 March 1884, the birthdate of Joyce’s wife Nora Barnacle. There may also be a hebdomadal level, covering one week, and an annual level, covering one year. In an earlier article in this series, in which I briefly explored these different planes of narrative, I wrote:

On the opening page of Finnegans Wake the phrase scraggy isthmus occurs (RFW 003.05). At an early date this was glossed as happy Xmas (McHugh 2006:3). Does this imply that, on some level, the book opens around Yuletide? In the penultimate chapter, the bells of Dublin’s churches ring in the New Year, and we are told that it is holyyear (RFW 443.02-09). A Holy Year was convoked by Pope Pius XI in 1925. This [annual] plane of narrative would seem to represent 1924.

Songs

These four paragraphs retell the story of the popular Irish-American ballad Finnegan’s Wake. But in this final paragraph, where the actual wake is depicted, there are snatches of two other popular “Oirish” songs, not to mention a pair of religious numbers. And as we saw above, there was also an allusion to the Scottish song Auld Lang Syne in the first draft of this paragraph, but for some reason Joyce removed it. The following are the obvious musical allusions:

- Finnegan’s Wake

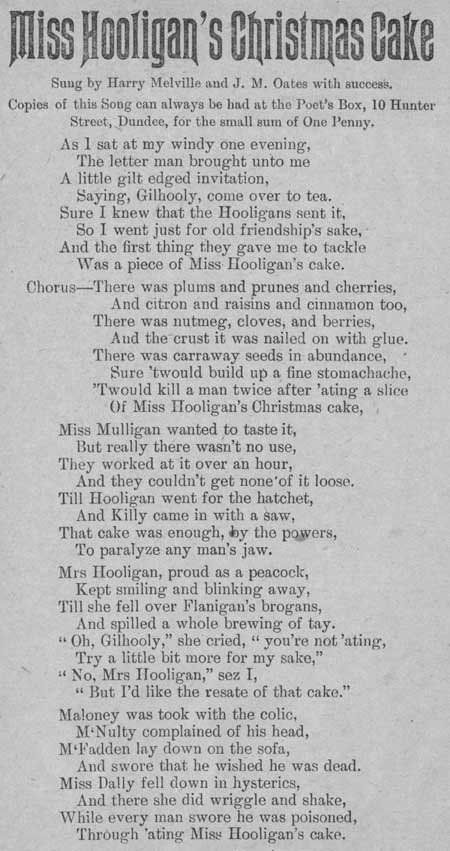

- Miss Hooligan’s Christmas Cake

- Phil the Fluther’s Ball

- Auld Lang Syne

- De Profundis

- Adeste Fideles

- Fidelio

Miss Hooligan’s Christmas Cake—Yuletide again!—was mentioned in an earlier article. According to his biographer Richard Ellmann, James Joyce was familiar with this popular ditty from an early age. Recording the memories of James’s childhood friend and neighbour, Eileen Vance, Ellmann writes:

But the best memory of all for Eileen Vance was the way the Joyce house filled up with music when May Joyce, her hair so fair that she looked to Eileen like an angel, accompanied John, and the children too sang. Stanislaus had for his specialty Finnegan’s Wake, while James’s principal offering for a time was Houlihan’s Cake. James’s voice was good enough for him to join his parents in singing at an amateur concert at the Bray Boat Club on June 26, 1888, when he was a little more than six. (Ellmann 27)

Miss Hooligan’s Christmas Cake made its first appearance in print in Dundee, Scotland, around 1890. But this was a reworking of an earlier song called Miss Fogarty’s Christmas Cake, composed in 1883 by the American songsmith Charles Frank Horn:

There were plums and prunes and cherries,

There were citrons and raisins and cinnamon, too.

Phil the Fluther’s Ball was written in 1880 by the Irish songwriter Percy French. It describes a ball which the indigent Phil holds to pay his rent:

Then all joined in wid the greatest joviality ...

... With the toot of the flute, and the twiddle of the fiddle, O!

Auld Lang Syne is too well-known to require any further comment.

The De Profundis is a Latin translation of Psalm 130 (Psalm 129 in the Latin Vulgate):

Out of the depths have I cried unto thee, O Lord. Lord, hear my voice: let thine ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications. If thou, Lord, shouldest mark iniquities, O Lord, who shall stand? But there is forgiveness with thee, that thou mayest be feared. I wait for the Lord, my soul doth wait, and in his word do I hope. My soul waiteth for the Lord more than they that watch for the morning: I say, more than they that watch for the morning. Let Israel hope in the Lord: for with the Lord there is mercy, and with him is plenteous redemption. And he shall redeem Israel from all his iniquities. (Psalm 130)

The De Profundis has been set to music by several composers, though no particular setting seems relevant to this passage. This work is traditionally associated with Irish wakes:

The corpse was laid on a large table in the kitchen with sheets forming a canopy over it. Usually the sheets were kept by richer farmers for use of the poor. Men went after night fall and none came [but] stopped until the women came in the morning to relieve the men. There was a big plate of snuff laid on the corpse for the women, and clay pipes for the men, also tobacco. When the men came, they would stand outside in groups until some man came and could say the De Profundis in Latin; he would say the prayer. After which that group entered. When another group gathered they did likewise. (John Reddin)

Adeste Fideles, or O Come, All Ye Faithful, is another traditional Latin hymn—this time associated with Christmas. Like Auld Lang Syne, it is too well-known to require any comment.

One might also mention Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, or Leonora, as he called it. Its subtitle is Conjugal Love, a major theme in Finnegans Wake. There is a very famous moment in the opera when the prisoners are allowed out of their cells, which Beethoven compares to the souls of the dead being released from Hell or Purgatory. The opera occupies a sort of no-man’s land between farce and tragedy: Leonora disguises herself as a boy, Fidelio, to gain admittance to the military prison where her husband Florestan is being incarcerated. Her descent into the dungeons to rescue her beloved has obvious Orphic overtones. It is also easy to see how Joyce may have connected Beethoven’s prison opera with Oscar Wilde’s prison epistle De Profundis.

Some annotators have detected allusions in this paragraph to a number of other songs:

- Pretty Molly Brannigan: “When I hear yiz crying around me, ‘Arrah, why did ye die?’”

- Johnny, I Hardly Knew Ye: “With guns and drums, and drums and guns.”

- Brian O’Linn

- Barnaby Finnegan: “I’m a decent gay laboring youth.”

- Mr McFinagan: “I’m a dacent labouring youth.”

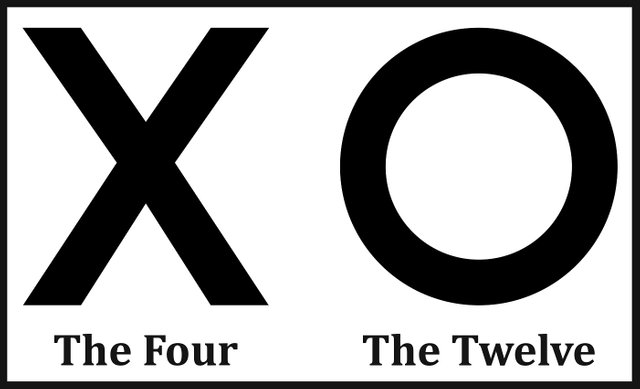

The Four Old Men and The Twelve

The Four Old Men are the historians or annalists of Finnegans Wake. Their immediate inspiration is the four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which Joyce conflated into Mamalujo: Matthew Gregory, Mark Lyons, Luke Tarpey and Johnny MacDougal. In an Irish context, however, they are the Four Masters, a quartet of 17th-century scholars who compiled the Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland.

As the historians of Finnegans Wake, the Four Old Men carry much of the book’s narration. Their familiar voices can be heard on almost every page. Each of them has his own particular accent and pet phrases. They are judges as well as historians, and are forever carrying out inquests (Inn Quests?), inquiries, interrogations. They sit in judgment on the other characters in Finnegans Wake. They try to get to the bottom of everything.

The Four Old Men also represent space: the four cardinal directions (North, South, East and West), and the four provinces of Ireland (Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connacht). Matthew Gregory is from Belfast, Mark Lyons from Cork, Luke Tarpey from Dublin, and Johnny MacDougal from Galway. In the early Middle Ages, there were five provinces in Ireland (the Middle Irish word for province, coiced, means fifth): this fifth province, Meath, is represented by Johnny MacDougal’s donkey or ass, who always accompanies the Four. Like Balaam’s ass in the Bible, Johnny MacDougal’s ass can talk. He is related to the ass that figures in the philosophy of Giordano Bruno. He is also a literary relative of Shakespeare’s Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Apuleius’s Lucius in The Golden Ass, both of whom are transformed into asses.

The Four Old Men embody senility and old age. The immortal struldbrugs of Gulliver’s Travels provided Joyce with the model:

[The struldbrugs] had not only all the follies and infirmities of other old men, but many more which arose from the dreadful prospect of never dying. They were not only opinionative, peevish, covetous, morose, vain, talkative, but incapable of friendship, and dead to all natural affection, which never descended below their grandchildren. Envy and impotent desires are their prevailing passions. But those objects against which their envy seems principally directed, are the vices of the younger sort and the deaths of the old. By reflecting on the former, they find themselves cut off from all possibility of pleasure; and whenever they see a funeral, they lament and repine that others have gone to a harbour of rest to which they themselves never can hope to arrive. (Swift )

In Irish mythology there is an antediluvian character called Fintan mac Bóchra, who is saved from the waters of the Universal Flood that he might be a lasting witness to the history of Ireland and the Western part of the world. Fintan had three partners, who were charged with recording the histories of the East, the North, and the South (Jubainville 80-81).

In many respects, The Twelve are adjuncts of the Four:

| The Four | The Twelve |

|---|---|

| Evangelists | Apostles |

| Space | Time |

| Judges | Jurymen |

| Seanad, or Irish Senate | Dáil, or Irish Parliament |

And like the Four, the Twelve have their own peculiar way of talking. In Finnegans Wake, they are always announced by a concatenation of sesquipedalian words of Latinate origin:

prostrated in their consternation and their duodisimally profusive plethora of ululation.

Remember Our Exagmination Round His Factification For Incamination of Work in Progress? In Joyce’s imagination, those essays were written by the Twelve.

The Twelve sometimes function as a Greek chorus. Or as regular customer’s in HCE’s pub, the Mullingar House.

The Universal Flood and the Apocalypse

Like Richard Wagner’s operatic tetralogy, The Ring of the Nibelung, Joyce’s Viconian tetralogy ends with a flood. In Wagner, the River Rhine overflows its banks and drowns the German landscape, washing away its sins and bringing an end to the World. In Finnegans Wake it is the River Liffey that bursts its banks and washes away the filth of Dublin. In each work, the water eventually flows back—ricorso—and the entire cycle begins again.

So, we should not be surprised to find references to Vico’s Universal Flood and the End of the World at the conclusion of this paragraph:

Tee the tootal of the fluid hang the twoddle of the fuddled, O.

Here, fluid is not only a literal reference to the waters of the Deluge, but also an echo of the word Flood. And it is not by chance that this four-paragraph evocation of the Viconian Cycle ends with the word O, or, in French, eau: water.

Note that there is also a reference to another type of fluid at the beginning of this sentence: tea. There is, however, so much that could be said about this humble decoction and its role in Finnegans Wake that I will leave it for another time.

With a bockalips of finisky fore his feet. And a barrowload of guenesis hoer his head.

This paragraph also has allusions to the Apocalypse (the last book of the Bible) and the end (Latin: finis) of the world, as well as to Genesis (the first book of the Bible) and the Creation of the World.

Perhaps that final O is also another ouroboros in the Book of Double Ends Joined?

References

- Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, Second Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1982)

- Marie Henri d’Arbois de Jubainville, Le Cycle Mythologique Irlandais et La Mythologie Celtique, Cours de Littérature Celtique, Volume 2, Ernest Thorin, Paris (1884)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- Marie Henri d’Arbois de Jubainville, Le Cycle Mythologique Irlandais et La Mythologie Celtique, Cours de Littérature Celtique, Volume 2, Ernest Thorin, Paris (1884)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Giambattista Vico, Goddard Bergin (translator), Max Harold Fisch (translator), The New Science of Giambattista Vico, Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY (1948)

Image Credits

- The Humours of an Irish Wake: Lewis Walpole Library, Anonymous, 1770, Fair Use

- Giambattista Vico: Francesco Solimena (artist), Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- The Deluge (Francis Danby): Tate Gallery, T01337, Francis Danby (artist), Fair Use

- Miss Hooligan’s Christmas Cake: Public Domain

- The Opening of the Sixth Seal (Francis Danby): Francis Danby (artist), Fair Use

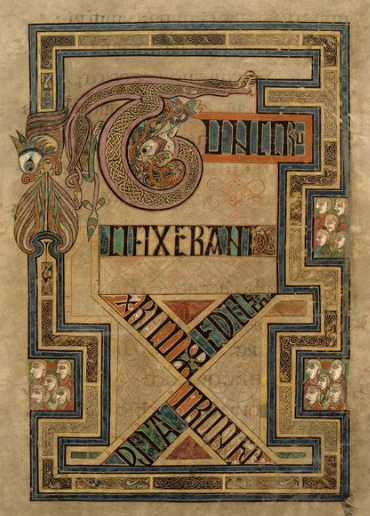

- Folio 124r of The Book of Kells: © 2012 The Board of Trinity College Dublin, Fair Use

Useful Resources

- Joyce Tools

- FWEET

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- Annotated Finnegans Wake (with Wakepedia)

- From Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay

- Miss Fogarty’s Christmas Cake

- Phil the Fluther’s Ball

Very nice post it was.

Posted using Partiko iOS

Very extraordinary post bro. Love you

Posted using Partiko iOS