Chest Cee!

The second part of the Humphriad—Finnegans Wake, Book I, Chapter 3—takes up the tale of HCE where the previous chapter left it down. Hosty’s Rann, The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly, has just received its world première in the streets of Dublin. This satirical account of HCE spreads like wildfire throughout the country. But what of the motley cast of characters whose rumours and innuendos birthed it in the previous chapter? What were the various fates of the dramatis personae in this Earwicker saga? The lengthy opening paragraph of this chapter comprises a series of obituaries for the more prominent of these characters—not unlike the death notices in a newspaper. The composers of the ballad are now decomposing.

In this article, we shall only examine the first thirteen-and-a-half lines of this paragraph. There are simply too many details in this long paragraph to do it justice in a single article.

First Draft

Joyce’s first draft of this paragraph comprises about fifteen lines of text. As usual, subsequent revisions fleshed out this initial sketch with a wealth of new details. In The Restored Finnegans Wake, the final version occupies two pages or seventy-nine lines. The lines we will be examining in this article grew out of the first twenty-five words of the first draft:

A cloud of witnesses indeed! Yet all these are as much no more as were they not yet or had they then not ever been. Of Hosty, quite a musical genius in small way, the end is unknown. O’Donnell is said to have enlisted at the time of the Crimean war under the name of Buckley. Peter Cloran, at the suggestion of the Master in Lunacy, became an inmate of an asylum. Treacle Tom passed away painlessly in a state of nature propelled into the great beyond by footblows of his last bedfellows, 3 Norwegian sailors. Shorty disappeared from the surface of the earth so completely as to lead one to suppose his habitat had become the interior. Then was the reverend, the sodality director that fashionable vice preacher to whom society ladies often became so enthusiasticaly attached and was a nondescript who sometimes wore a raffle ticket in his hat & was openly guilty of malpractice with his tableknife the cad with a pipe encountered by HCE? (Hayman 69)

This early draft opens with a meteorological metaphor. Bad weather and poor visibility are common themes throughout this chapter, representative of the obscurity of the past into which we are peering. It is interesting to note that this theme was present from the very beginning. The phrase cloud of witnesses was lifted from the Bible:

Wherefore seeing we also are compassed about with so great a cloud of witnesses, let us lay aside every weight, and the sin which doth so easily beset us, and let us run with patience the race that is set before us, Looking unto Jesus the author and finisher of our faith; who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is set down at the right hand of the throne of God. For consider him that endured such contradiction of sinners against himself, lest ye be wearied and faint in your minds. (Hebrews 12:1-3)

The following sentence is also of Biblical origin, this time from the Apocryphal Book of Sirach:

And there are some, of whom there is no memorial: who are perished, as if they had never been: and are become as if they had never been born, and their children with them. (Sirach 44:9)

Also present at the outset were the six obituaries of Hosty and his colleagues. Here, these six individuals are identified as: Hosty, O’Donnell, Peter Cloran, Treacle Tom, Shorty, and the reverend, the sodality director. In the published version, these become: Osti-Fosti, A’Hara, Paul Horan, Sordid Sam, Langley, and the reverend, the sodality director.

O’Donnell’s enlisting in the Crimean War under the name Buckley anticipates Chapter II.3 (The Scene in the Public), which will recount How Buckley Shot the Russian General. The Russian General is HCE and Buckley is his eternal enemy, the Oedipal character who supplants him. Of course, all six characters are versions of this Oedipal figure. There are a few other allusions to the Crimean War in the final draft. For example, the French Zouaves (those zouave players), the Battle of Inkerman (Inkermann) and Tennyson (Tuonisonian), whose narrative poem The Charge of the Light Brigade is set during the Battle of Balaclava.

The final sentence asks the question: “Was the reverend (ie the sodality director) the same person as the cad with a pipe?” In the published version, this question is expanded to thirteen lines, with the reverend, the sodality director separated from the cad (that same snob of the dunhill) by no less than eight lines. But the gist of the first draft is unchanged. Note that the first draft’s enthusiasticaly is corrected to enthusiastically.

We are told that the reverend sometimes sported a raffle ticket in his hat. In Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Mad Hatter’s top hat has a price tag on it, labelled: In this Style 10/6 (ie ten shillings and sixpence). In the final draft, raffle becomes raffles and the hat is worn all to one side. A J Raffles was a gentleman thief created in 1898 by E W Hornung, the brother-in-law of Arthur Conan Doyle. Raffles was partly inspired by Hornung’s friend Oscar Wilde. One of Napoleon Sarony’s celebrated photographs of Oscar Wilde depict him wearing a fedora all to one side. The photograph was taken in Sarony’s studio in New York in 1882, the year of Joyce’s birth.

Oaths

This extract opens with three oaths:

Chest Cee! JC! Jesus C! In Ireland, it is common to alter religious oaths in order to avoid taking the Holy Name in vain. This is called dodging the curse. In the opening episode of Ulysses, Buck Mulligan remarks: “Janey Mack, I’m choked.” Janey Mack is substituted for Jesus Jack, which is already one remove from Jesus Christ!

’Sdense! ’Sdeath!, a common Shakespearean oath. An altered version of God’s Death!, this is another example of dodging the curse.

Corpo di baraggio! Corpo di Bacco [Italian for Body of Bacchus], a mild oath in Italy, similar to By Jove! The Italian barraggio means dam, which suggests damn! another oath.

The last word of Hosty’s Rann, which closed the preceding chapter, is Cain. In Genesis 4, Cain is cursed for murdering his brother Abel and is condemned to be a wandering exile. I presume that Hosty and his colleagues have brought the same curse and fate upon themselves by “murdering” HCE’s reputation.

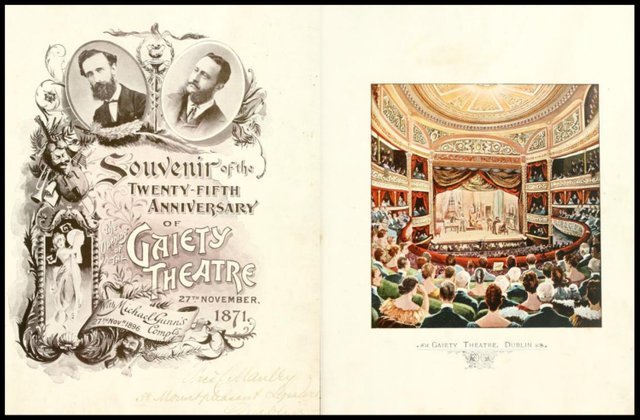

In the previous article, we saw how Chest Cee! is also a musical allusion, referring to Hosty’s singing voice. Joyce borrowed this allusion from the Souvenir of the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Opening of the Gaiety Theatre, the king’s treat house in which HCE was simultaneously fêted and ridiculed in the previous chapter:

Old-fashioned Italian Opera, properly so-called, had long become almost a thing of the past, and strange, perhaps, as it may appear, there are many left who still lament it. After all, who that has seen him can ever forget the operatic tenor of the old school? Some may even think conventional opera would be worth preserving, if only for the sake of his few survivors—the gentleman who so strangely and wonderfully used to work himself up to the point of delivering his famous chest C. One always knew when it was coming. Its owner would take a few strides towards the back of the stage, accumulating lung power the while, and then return to the footlights to expend it for the benefit of the audience and the glory of himself. (J B H 31)

Bad Weather

Joyce also retains the meteorological theme that was present in the first draft. The low visibility is stressed and is a recurring theme throughout this chapter:

Chest Cee! Just see

’Sdense! Dense

spoof of visibility Spooks—ie ghosts or phantoms—are usually invisible or difficult to make out.

freakfog A freak fog is a sudden and unexpected bank of fog. The Battle of Inkerman, alluded to in line 9, was fought in the fog.

kingsrick of Humidia Kingrick is an obsolete Middle English term for kingdom. Ireland is notorious for its humid climate.

a poisoning volume of cloud barrage The meteorological theme is also present in the word barrage. In a military context, a barrage is a heavy curtain of artillery fire laid down to obscure the visibility of one’s own troops. In World War I, a cloud barrage was a cloud of phosphorus pentoxide gas (white phosphorus) used as a smoke-screen to conceal troop movements. Unlike mustard gas, however, phosphorus pentoxide is not particularly poisonous. During the Battle of Inkerman, the Russian infantry used the foggy conditions as a natural cloud barrage to cover their two advances. Ironically, the fog also hid the vulnerable position of the British forces following the second Russian advance, allowing the British to recover and counterattack before the Russians could be reinforced.

English Elements

In the previous article, we saw how John Gordon, Professor Emeritus of English at Connecticut College, has referred to I.3 as the Wake’s ‛English’ chapter:

The scene and characters tend to be English. HCE’s ‛regifugium persecutorum’ is now England, and he is uncommonly, and unguardedly, proud of his British connections ... so much so that at the chapter’s end the one hundred and eleven epithets directed against him are ... equated with the one hundred and eleven anti-English votes of the Irish Parliament against the Act of Union. Most of all, the chapter is stereotypically ‛English’ in its voice. (Gordon 129)

In that article, I attributed this English quality to the fact that Joyce conceived the vignette Here Comes Everybody—the forerunner of the Humphriad—when he was holidaying in Bognor in the southeast of England.

But as Gordon points out, others have suggested a connection with the first and unsuccessful attempt to have the Act of Union (yoking Ireland to England) passed by the Irish Parliament in 1799 (Gordon 129, Boldereff 2:181, Staples 3-6). The Irish memoirist Jonah Barrington, who was then Member of Parliament for the City of Clogher, has left us this record of the momentous event:

After the most stormy debate remembered in the Irish Parliament, the question was loudly called for by the Opposition, who were now tolerably secure of a majority, never did so much solicitude appear in any public assembly; at length above sixty members had spoken, the subject was exhausted, and all parties seemed impatient. The House divided, and the Opposition withdrew to the Court of Requests. It is not easy to conceive, still less to describe, the anxiety of that moment; a considerable delay took place. Mr. Ponsonby and Sir Laurence Parsons were at length named tellers for the amendment; Mr. W. Smith and Lord Tyrone for the address. One hundred and eleven members had declared against the Union, and when the doors were opened, one hundred and five was discovered to be the total number of the Minister’s adherents. The gratification of the Anti-Unionists was unbounded; and as they walked deliberately in, one by one, to be counted, the eager spectators, ladies as well as gentlemen, leaning over the galleries, ignorant of the result, were panting with expectation. Lady Castlereagh, then one of the finest women of the Court, appeared in the Serjeant’s box, palpitating for her husband’s fate. The desponding appearance and fallen crests of the Ministerial benches, and the exulting air of the opposition members as they entered, were intelligible. [Footnote: Mr. Egan, Chairman of Dublin County, a coarse, large, bluff, red-faced Irishman, was the last who entered. His exultation knew no bounds; as No. 110 was announced, he stopped a moment at the Bar, flourished a great stick which he had in his hand over his head, and with the voice of a Stentor cried out, “And I’m a hundred and eleven .” He then sat quietly down, and burst out into an immoderate and almost convulsive fit of laughter; it was all heart. Never was there a finer picture of genuine patriotism.] (Barrington 405)

This could account for an indirect allusion to the Irish Parliament in this passage. In the previous chapter, one of Hosty’s colleagues, O’Mara, the ex-private secretary of no fixed abode, was seen sleeping in a doorway of the Bank of Ireland—the former seat of the Irish Parliament. In this chapter, he is identified as A’Hara, an exile who dies abroad.

Curiously, there are no obvious English allusions in the first draft. But in the final draft, English elements appear from the outset:

’Sdense As we have seen, ’Sdeath is a Shakespearean oath.

freakfog The foggy weather on the first page evokes the pea-soup “particulars” of Victorian and Edwardian London.

Blackfriars Black Friars Lane was the site of the Dominican Monastery where Cardinal Wolsey convened an ecclesiastical court to determine the validity of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. This was a mixed sex case. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, Henry committed Bigamy when he subsequently married Anne Boleyn. Blackfriars Theatre, which was built on the same site, was used by Shakespeare’s company as a winter playhouse. It is quite possible that the play The Life of King Henry the Eighth, which was written by Shakespeare and Fletcher, was performed here. Shakespeare—The Bard—was of that family of bards. The story of Tristan and Isolde, which features prominently in Finnegans Wake, involves another mixed sex case—see below for its relevance here.

liddled Alice Pleasance Liddell, the muse and child-friend of Lewis Carroll and the inspiration for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

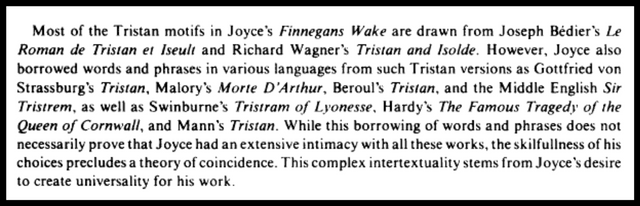

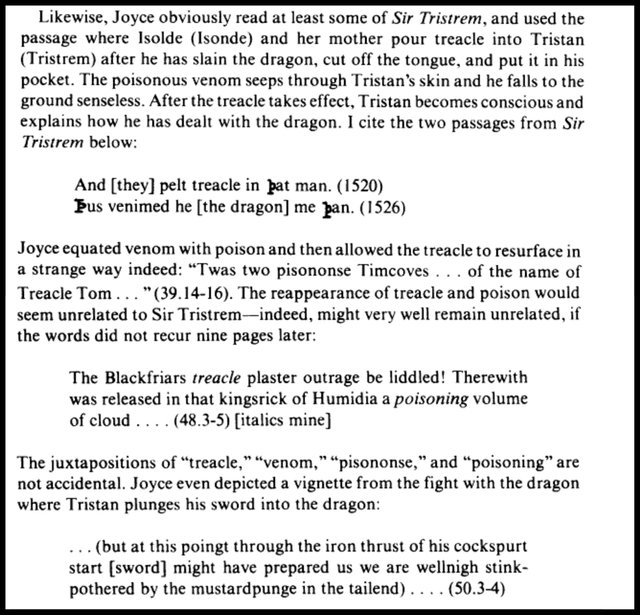

treacle plaster outrage These three words pack a wealth of literary allusions. The best analysis I know is Charles Long’s article Finnegans Wake: Some Strange Tristan Influences, which was published in The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies in 1989. It is well worth reading.

Long’s research into these various works has shed some welcome light on Joyce’s mysterious use of the term treacle in Finnegans Wake:

This casts in a new light the painting of St Michael & the Dragon in HCE and ALP’s bedroom in the Mullingar House—the contest between Michael the Archangel and Old Nick will be reenacted as The Mime of Mick, Nick and the Maggies in Chapter II.1, which is alluded to in lines 9-10. Both characters are yoked together on the next page as Micholas de Cusack (Michael Cusack and Nicholas of Cusa).

Treacle Town is a nickname for Bristol. In 1172, Henry II granted the city of Dublin as a colony to my men of Bristol. Bristol lies in the southwest of England, not too far from Cornwall, where Tristan’s uncle King Mark had his kingdom. In Act 3 of Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde, a delirious Tristan tears off his bandages (plasters?), causing his wounds to reopen. Treacle plaster was also the name given to the sticky brown paper used by burglars to quietly remove panes of glass. Is Joyce is referring to a specific case of burglary involving treacle plaster?

It can hardly be a coincidence that two more English elements in this passage take us to Cornwall:

Hilton St Just St Just

Ivanne Ste Austelle St Austell

In Ulysses Hilton St Just and Ivan St Austell are identified as popular tenors:

Besides, though taste latterly had deteriorated to a degree, original music like that, different from the conventional rut, would rapidly have a great vogue, as it would be a decided novelty for Dublin’s musical world after the usual hackneyed run of catchy tenor solos foisted on a confiding public by Ivan St Austell and Hilton St Just and their genus omne. (Ulysses 617)

They sang with the Arthur Rousbey Opera Company, which performed several times in Dublin between 1894 and 1898. Both names are pseudonyms derived from the two Cornish towns (Adams 73). Note that Ivan St Austell has been transformed into a female singer. His real name was W H Stephens. Arthur Rousbey was also a pseudonym, being the stage name of James Huntress, who had been a bass-baritone with the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company. Is it just a coincidence that Rousbey’s actual surname is feminine?

- kingsrick Does this allude to two other Shakespearean English kings, Richard II and Richard III?

One final “English” element may be noted:

- Caraculacticors Caratacus (or Caractacus) was the British chieftain who resisted the Roman conquest of Britain between 43 and 50 CE. His kingdom lay in the east of what is now England, between the Thames and the Wash. Here, he is associated with Vergobretas. A vergobret was a magistrate or judge in ancient Gaul. He held the highest office among several Gallic tribes, especially the Aedui. In his Commentaries on the Gallic War, Caesar discusses the role of the vergobret. Etymologically speaking, the word means one who works judgment. I can understand why Joyce gives us Caraculacticors: it not only adds to the English elements in this passage, but also clearly alludes to character actors. But what is the relevance of a Gallic judge? Perhaps there is an allusion to verger, a layperson who assists in a religious service. The Trial Scene in Henry VIII, which takes place in a hall in Blackfriars, opens with the entrance of two vergers. Henry’s Lord Chancellor Cardinal Wolsey and the Papal Legate Cardinal Campeius are the two judges who preside at this trial.

Theatre and Drama

In this paragraph, Hosty and his associates are regarded as the dramatis personae of a play, or as the members of a repertory theatre. Some theatrical allusions have already been noted:

Blackfriars Blackfriars Theatre, and the site of the Trial Scene in Shakespeare & Fletcher’s The Life of King Henry the Eighth (Act 2 Scene 4)

that family of bards The Bard, or Shakespeare

Caraculacticors Character Actors

Several other theatrical allusions in this passage were lifted by Joyce from the Annals of the Theatre Royal, Dublin (Levey & O’Rorke 11, 19, 49, 67-72). This particular Theatre Royal, the third in Dublin to bear that name, was on Hawkins Street and opened its doors in 1821. The “Old Royal” was destroyed by fire in February 1880. Its final manager was Michael Gunn, who also managed the Gaiety Theatre. The fourth Theatre Royal was built on the same site (see photograph above) and flourished from 1897 till 1934. I’m sure Joyce must have patronized this particular theatre in his day.

Fin M‛Cool and the Fairies of Lough Neagh and Gulliver were pantomimes regularly performed in the Theatre Royal. Several other popular pantos featured the character Harlequin. Hurley and Quinn are common Irish surnames.

Mr Frank Smith and Mr J F Jones were the real names of two singers whose stage names were Vyvyan and S Vincent. In 1879 they took part in a most successful performance of the Irish the opera Maritana— (Levey & O’Rorke 67).

The reference to Coleman of Lucan taking four parts is worthy of note:

Engagement of Mr. John Coleman for twelve nights. The new dramatic Romance by Algernon Willoughby, “Valjean” (founded on Victor Hugo’s work, “Les Miserables”), in which Mr. Coleman assumed four characters: Jean Valjean, M. Madeline, The Fugitive, and Urban Le Blanc. The rapid change of dress accomplished by Mr. Coleman, and his marked difference of appearance in this drama, made it difficult to believe that it could be the same individual who appeared in each separate part. (Levey & O’Rorke 68)

The authors do not seem to realize that these are not four characters but Jean Valjean under four different names. The blending of characters into one another is a common cause of confusion in Finnegans Wake.

Zouave Players

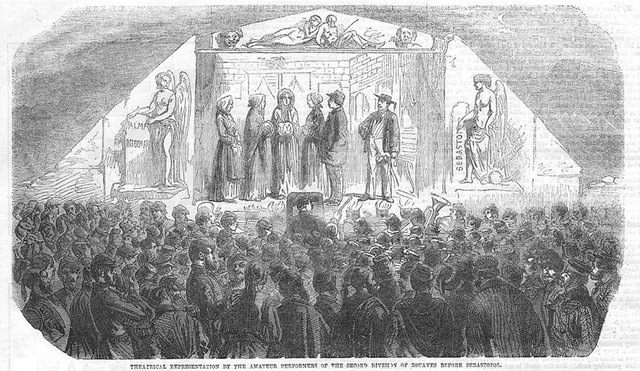

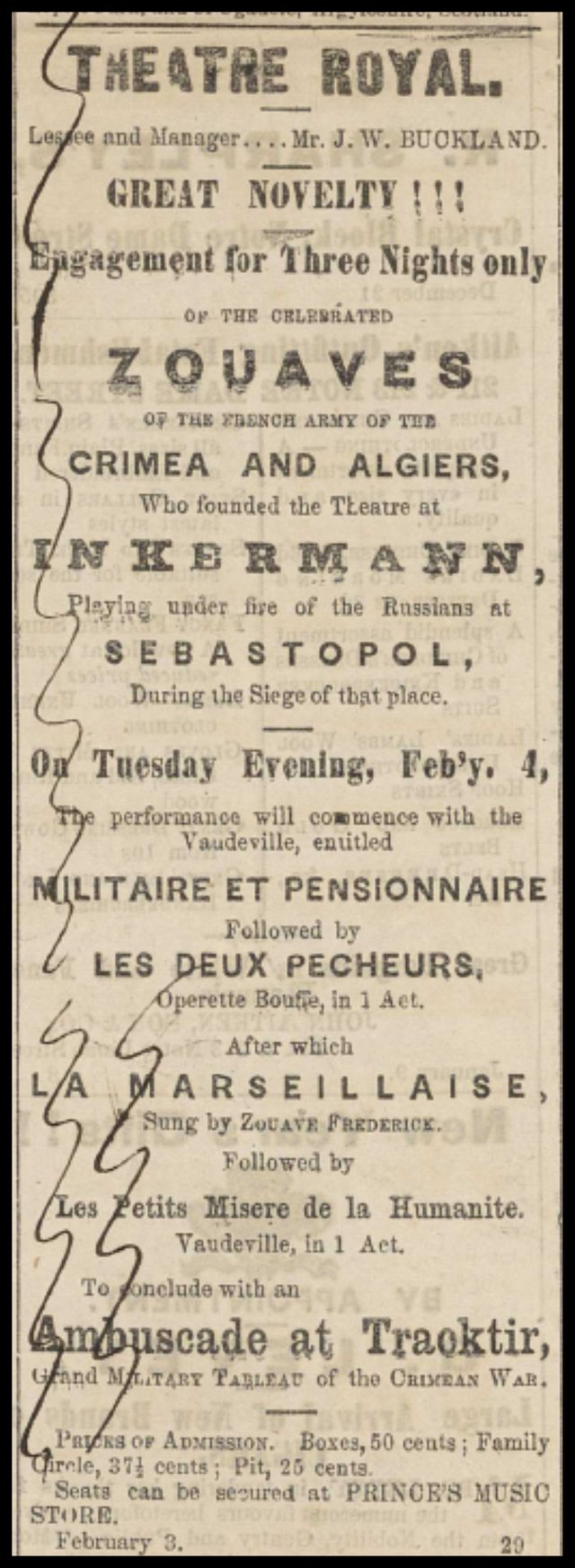

That the zouave players of Inkermann is another borrowing from the Annals of the Theatre Royal is obvious due to the incorrect—but all too common—spelling of Inkerman, which Joyce retains:

[1860] October 8th. Appearance of “The Zouave Artistes,” announced as “The original Founders of the Theatre at Inkermann, during the Crimean War, where, under the enemy’s fire, they gained such renown, and have since performed in all the principal cities in Europe.”

NOTE “The military papers proving the authority of the Zouaves may be seen at the Box Office”

The Zouaves acted and sang capitally, the female parts being performed by men. (Levey & O’Rorke 46)

Originally, the Zouaves comprised a regiment of Light Infantry in the French Army. They were first recruited in 1831 in Algeria, primarily from a Berber tribe known as the Zwawa or Zouaoua. (The ancient kingdom of Numidia was centred on Algeria—hence the toponym Humidia in line four.) Later regiments of Zouaves were recruited almost exclusively from Europeans but continued to sport the extravagant and colourful uniforms of the Berbers. During the Second Empire, the Zouaves took part in the Crimean War and distinguished themselves in several engagements. This was the first time they saw service outside Algeria. At a critical point in the Battle of Inkerman, which was fought in the fog on 5 November 1854, the Zouaves came to the relief of the British Guards, thwarting an attempt by the Russians to outflank them.

At the Battle of Malakoff (8 September 1855), in which the Zouaves played a decisive role, they were led by Général Patrice MacMahon, a veteran of Irish extraction. Following the capture of the Russian redoubt of Malakoff, MacMahon, having been advised to withdraw, is alleged to have responded: J’y suis, j’y reste [Here I am and here I’m staying]. Horace Vernet’s celebrated painting of the taking of the redoubt depicts the Zouave Eugène Libaut raising the French tricolour.

It was during their service in the Crimea that the Zouaves created a Theatre at Inkerman. After the war, members of this troupe continued to perform on stages across the world. Their repertory consisted primarily of:

French Vaudevilles, Opéras Bouffes, Operettas, etc., with the introduction of popular and patriotic songs, and Grand Military Spectacular Scenes, showing how the French army was amused in its hours of repose, and how the carnage fields of the Crimea were won from the hardy and valorous Russians. (Daily Advocate, 21 April 1861, Baton Rouge, Louisiana)

The Four and The Twelve

We have already met The Four and The Twelve, two groups of male characters who play important roles in Finnegans Wake. Here they are again:

Coleman of Lucan taking four parts, a choir of the O’Daley O’Doyles doublesixing the chorus ... (RFW 039.11-12)

The Four: Four senile old men who spend most of their time drinking and reminiscing about the past in the Mullingar House, the pub in Chapelizod where Finnegans Wake is set.

The Twelve: Twelve regular patrons of the Mullingar House.

The Four Old Men are the historians or annalists of Finnegans Wake. Their immediate inspiration is the four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which Joyce conflated into Mamalujo: Matthew Gregory, Mark Lyons, Luke Tarpey and Johnny MacDougal. In an Irish context, however, they are the Four Masters, the quartet of 17th-century scholars who compiled the Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland.

As the historians of Finnegans Wake, the Four Old Men carry much of the book’s narration. Their familiar voices can be heard on almost every page. Each of them has his own particular accent and pet phrases.

The Four are judges as well as historians. They are forever carrying out inquests (Inn Quests?), inquiries, interrogations. They sit in judgment on the other characters in Finnegans Wake. They try to get to the bottom of everything.

The Four Old Men also represent space: the four cardinal directions (North, South, East and West), and the four provinces of Ireland (Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connacht). Matthew Gregory is from Belfast, Mark Lyons from Cork, Luke Tarpey from Dublin, and Johnny MacDougal from Galway.

In the early Middle Ages, there were five provinces in Ireland (the Middle Irish word for province, coiced, means fifth): this fifth province, Meath, is represented by Johnny MacDougal’s donkey or ass, who always accompanies the Four. Like Balaam’s ass in the Bible, Johnny MacDougal’s ass can talk. He is related to the ass that figures in the philosophy of Giordano Bruno. He is also a literary relative of Shakespeare’s Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Apuleius’s Lucius in The Golden Ass, both of whom are transformed into asses.

The Four Old Men embody senility and old age. The immortal struldbrugs of Gulliver’s Travels provided Joyce with the model:

[The struldbrugs] had not only all the follies and infirmities of other old men, but many more which arose from the dreadful prospect of never dying. They were not only opinionative, peevish, covetous, morose, vain, talkative, but incapable of friendship, and dead to all natural affection, which never descended below their grandchildren. Envy and impotent desires are their prevailing passions. But those objects against which their envy seems principally directed, are the vices of the younger sort and the deaths of the old. By reflecting on the former, they find themselves cut off from all possibility of pleasure; and whenever they see a funeral, they lament and repine that others have gone to a harbour of rest to which they themselves never can hope to arrive. (Swift 221)

In Irish mythology there is an antediluvian character called Fintan mac Bóchra, who is saved from the Deluge to be a lasting witness to the history of Ireland and the West. Fintan had three partners, who were charged with recording the histories of the East, the North, and the South (Jubainville 80-81).

In many respects, the Twelve are adjuncts of the Four:

| The Four | The Twelve |

|---|---|

| Evangelists | Apostles |

| Space | Time |

| Judges | Jurymen |

| Seanad, or Irish Senate | Dáil, or Irish Parliament |

The Twelve sometimes function as a Greek chorus, commenting on the action of the novel. They are the twelve good citizens, regular patrons of HCE’s tavern. As an embodiment of time, their siglum is simply a watch dial. This is one reason why they are sometimes named Sullivans (echoing the Irish: súil amháin, one eye) or Doyles (echoing dials). The latter name also evokes Dáil, as The Twelve are Parliamentarians to The Four’s Senators. There is also an obvious allusion to the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, which was famous for its performances of the operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan.

The twelve Roman numerals that were once found on old watch dials represent the Twelve Tables of Roman Law, as The Twelve are also twelve jurymen. Like the Four, the Twelve have their own peculiar way of talking: in highfalutin Latinate words ending in -ation. Remember Our Exagmination Round His Factification For Incamination of Work in Progress?

In this passage, both The Four and The Twelve appear in a theatrical setting. The Four are associated with Lucan, a village a few kilometres upstream from Chapelizod, on the opposite bank of the River Liffey. The Twelve are split into two groups of six: the O’Daleys and the O’Doyles. The Lucan Spa Hotel is mentioned in the Annals of the Theatre Royal. Perhaps that is the only reason for Lucan’s appearance here.

And where is Johnny MacDougal’s ass? Is he the zitherer of the past who brings up the rear? I don’t think so. An intermediate draft of this passage ran thus:

Sdense! Therewith was released a poisoning volume of cloud indeed! Yet all they who heard or redelivered are now as much no more as be they not yet now or had they then notever been. Canbe in some future we shall presently here the zitherer of the past with his merrymen all, zimzim zimzim. (James Joyce Digital Archive)

So the zitherer was introduced before The Four or The Twelve. I believe the zitherer of the past and his merrymen all refers to Hosty and his colleagues. Hosty does not play the zither, but he does accompany his singing with the thrummings of a crewth fiddle (RFW 033.03). The Welsh crwth was a zither-like instrument which one played by bowing four of its six strings, while plucking the remaining two. By thrumming his crwth, Hosty has turned it into a zither. For the record, a zither-player is called a zitherist, not a zitherer.

This may be one of those rare occasions on which the Four Old Men are not accompanied by the donkey.

Zimzim Zimzim

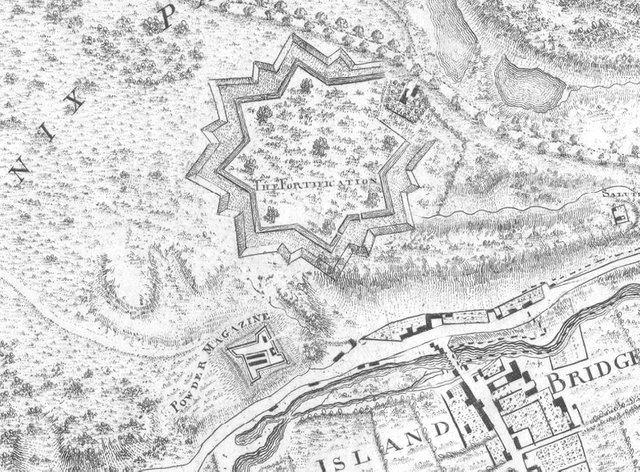

One of the recurrent leitmotifs that pops up again and again in the pages of Finnegans Wake is an alliterative phrase usually associated with the Magazine Wall—that is, the wall of the Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park:

MAGAZINE FORT, PHOENIX PARK (12/34). At the SE corner of the “Fifteen Acres,” on St Thomas’s Hill in the Park. Built on the site of the old Phoenix or Fionn Uisge House in 1801. The buildings of the Magazine are surrounded by a ditch and wall. Even in his madness, Swift quipped: “Behold a proof of Irish sense,/Here Irish wit is seen;/When nothing’s left that’s worth defence,/They build a magazine.” The “Starfort” ... was a different fortification, to the N of the Magazine Fort. The crash (Fimfim Fimfim, etc) which usually appears with references to the Magazine Wall is the fall of Humpty Dumpty and of HCE. (Mink 394, slightly emended)

To this may be added a few other interesting details:

In 1609 Sir Richard Sutton was granted [Ashtown Castle, in the Phoenix Park] at Kilmainham and surrounding lands and by 1611 he had assigned this land to Sir Edward Fisher. Fisher’s lands included all lands north of the Liffey from Oxmantown to Chapelizod which comprised 330 acres of the Kilmainham castle demesne and 60 acres known as Kilmainham Wood. Sir Edward erected a country house at Thomas’s Hill believed to have once been known as Isolde’s Hill. The house was named “ Phoenix”. In 1618 Fisher surrendered his lands to the King. The Crown purchased additional lands at Chapelizod, Grangegorman, Castleknock and Ashtown. These lands form the core of the park. The “Phoenix” was used as a viceregal residence up to 1665. The house was demolished in 1734 to make way for the powder magazine or Magazine Fort. (Phoenix Park)

Thomas’s Hill is possibly named for the engineer and architect Thomas Burgh, who designed and erected a star fort close by in 1710. The star fort, which was constructed of earthen embankments, was never completed. It was demolished in 1837:

FWEET lists about a dozen instances of the zimzim zimzim motif. It seems that Joyce first introduced it when he was drafting the opening chapter of the book:

By the mausoleme wall. Finnfinn Fannfann. With a grand funferall. Fumfum fumfum! (Hayman 53 [RFW 011.04-05])

This is the only instance of this motif that occurs in Hayman’s First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake. All the other instances were added to later drafts.

But what does it mean? The fall of Humpty and HCE are certainly associated with the wall of the Magazine Fort (see Hosty’s Rann). The Wall Street Crash is also relevant here. But zimzim zimzim and all its variations sound more like bells, buzzes, or musical notes than an onomatopoeic representation of a crash or of the breaking of an egg. Could it represent the sound of the servant’s bell in the Mullingar House (there is a bell-pull or buzzer in the master bedroom)? Or is it the bell that sounds when a customer enters HCE’s pub (which doubled as a general store)? Or is it music on the radio, which was referred to as Wheatstone’s magic lyer immediately after the first appearance of the motif (RFW 011.06)?

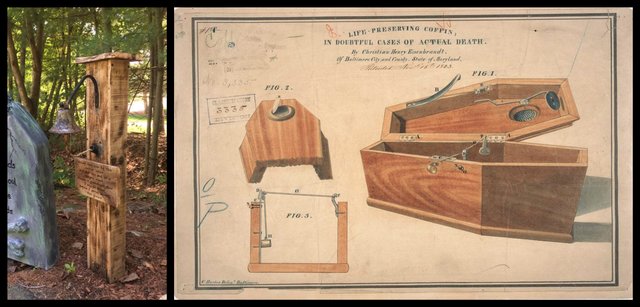

Perhaps it is all or none of the above. I am going to suggest an alternative meaning. In the 19th century, the fear of being buried alive led to a “lively” trade in so-called safety coffins, each of which was equipped with an alarm bell that the occupant could ring should he revive after his interment. The zimzim zimzim motif is often linked to death and burial—see its first appearance above—and the concept of life after death is central to Finnegans Wake.

The ringing of the sacring bell during Holy Mass may also be relevant. The Eucharist celebrates Christ’s sacrificial death and subsequent resurrection. In a passage in Ulysses, Stephen imagines the ringing of this bell:

And at the same instant perhaps a priest round the corner is elevating it. Dringdring! And two streets off another locking it into a pyx. Dringadring! And in a ladychapel another taking housel all to his own cheek. Dringdring! Down, up, forward, back. Dan Occam thought of that, invincible doctor. A misty English morning the imp hypostasis tickled his brain. Bringing his host down and kneeling he heard twine with his second bell the first bell in the transept (he is lifting his) and, rising, heard (now I am lifting) their two bells (he is kneeling) twang in diphthong (Ulysses 40)

But what is the significance of the Magazine Fort in all of this? I believe this is a logical choice for three reasons:

Firstly, in Finnegans Wake the Phoenix Park represents the Garden of Eden, the scene of the Fall of Man. So Joyce wanted to associate HCE’s fall with some prominent feature in the park.

Secondly, the association of HCE’s fall with that of Humpty Dumpty meant that this prominent feature had to have a wall.

Thirdly, the Magazine Fort was built on the site of Phoenix House, a country house constructed around 1611 by Sir Edward Fisher. For millennia, the mythical phoenix has been a potent symbol of death and resurrection.

The Earwicker Household

There is one last mystery to unlock in these thirteen-and-a-half lines. What does the phrase goats, hill cat and plain mousey, Bigamy Bob and his old Shanvocht mean? Why does Joyce choose these particular creatures? What was his source? There are no obvious answers to these queries. Do the five creatures refer to the members of the Earwicker family?

There is also a pair of contraries here:

| hill cat | plain mousey |

|---|---|

| hill | plain |

| cat | mouse |

| hellcat | mousey |

I can’t explain any of this, and none of it is terribly convincing. Hellcat and mousey are generally applied to females, which suggests that this pair of contraries represents Issy’s two personalities (often symbolized by DOVE and RAVEN). This would explain why goats is plural: it represents both the twins, Shem and Shaun.

| Creature | Identity |

|---|---|

| goats | Shem & Shaun |

| hell cat | Bad Issy |

| plain mousey girl | Good Issy |

| bigamist | HCE |

| poor old woman | ALP |

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Robert Martin Adams, Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Oxford University Press (1967)

- James S Atherton, The Books at the Wake: A Study of Literary Allusions in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, IL (1959, 2009)

- Jonah Barrington, Rise and Fall of the Irish Nation, P J Kennedy, New York (1896)

- Vicki Betts, [Baton Rouge, LA] Daily Advocate, September 3,

1860-October 25, 1861, University of Texas at Tyler, Tyler, TX (2016) - Frances Motz Boldereff, Reading Finnegans Wake, Classic Nonfiction Library, Woodward, PA (1959)

- John Gordon, Finnegans Wake: A Plot Summary, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse NY (1986)

- J B H et al, Souvenir of the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Opening of the Gaiety Theatre: 27th November 1871, Gaiety Theatre, Dublin (1896)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, TX (1963)

- Samuel Carlyle Hughes, The Pre-Victorian Drama in Dublin, Hodges, Figgis, & Co, Ltd, Dublin (1904)

- James Joyce, Ulysses, Shakespeare & Company, Paris (1922)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce et al, The Letters of James Joyce, Volume I, Stuart Gilbert (editor), Volumes II and III, Richard Ellmann (editor), Viking Press, New York (1957, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Marie Henri d’Arbois de Jubainville, Le Cycle Mythologique Irlandais et La Mythologie Celtique, Cours de Littérature Celtique, Volume 2, Ernest Thorin, Paris (1884)

- Richard Michael Levey, J O’Rorke, Annals of the Theatre Royal, Dublin, Joseph Dollard, Dublin (1880)

- Charles Long, Finnegans Wake: Some Strange Tristan Influences, The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, Volume 15, Number 1, Pages 23-33, Canadian Association for Irish Studies, Montreal (1989)

- Louis O Mink, A Finnegans Wake Gazetteer, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN (1978)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Hugh B Staples, Some Notes on the One Hundred and Eleven Epithets of HCE, A Wake Newslitter, New Series, Volume 1, Number 6 (December 1964), Pages 3-6, Split Pea Press, Edinburgh (1999)

- Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, The Prose Works of Jonathan Swift, D. D., Volume VIII, Edited by G Ravenscroft Dennis, George Bell & Sons, London (1905)

- Giambattista Vico, Goddard Bergin (translator), Max Harold Fisch (translator), The New Science of Giambattista Vico, Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY (1948)

Image Credits

- The Cad with a Pipe: © John Vernon Lord (artist), Fair Use

- The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly: © Carol Wade (artist), Fair Use

- The Mad Hatter’s Tea Party: John Tenniel (artist), Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Public Domain

- Charge of the Light Brigade: Richard Caton Woodville, Jr (artist), Palacio Real de Madrid, Public Domain

- Oscar Wilde in 1882: Napoleon Sarony (photographer), Union Square, New York, Number 26 (1882), Public Domain

- Souvenir of the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Opening of the Gaiety Theatre: Dollard Printing House, Dublin, Public Domain

- St Paul’s from the Surrey Side: Charles-François Daubigny (artist), The National Gallery, London, Public Domain

- Night Attack with White Phosphorus Bomb at Gondrecourt-le-Château (15 August 1918): Library of Congress Online Catalog, Lot Number 8876, Public Domain

- Playhouse Yard, London (Site of Blackfriars Monastery and Theatre): © Inspiring City, Fair Use

- The Fourth Theatre Royal, Dublin (Hawkins Street): Eason Photographic Collection, EAS 1700, National Library of Ireland, Public Domain

- The Third Theatre Royal (1821): George Petrie (artist), Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, Public Domain

- The Zouave Theatre at Inkerman: Theatrical Entertainment by Zouaves at Sevastopol, Cassell's Illustrated Family Paper, London (1855), Public Domain

- The Zouaves Come to the Relief of the British Guards at the Battle of Inkerman: © British Battles, Fair Use

- The Taking of the Malakoff Redoubt: Horace Vernet (artist), Prise de la tour de Malakoff, 8 septembre 1855 (cropped), Musée Rolin Autun, Saône-et-Loire, France, © Denis Trente-Huittessan (photographer), Fair Use

- Advertisement for the Zouave Players (Montreal Herald 3 February 1863): Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, Volume 54, Number 29, Public Domain

- Waterbury Pocket Watch: Waterbury Pocket Watch and Original Box (1890), © 2020 Sellingantiques Ltd, Fair Use

- Zither: Franz Schwarzer Zither Company (manufacturer), Missouri History Museum, St Louis, MO, Public Domain

- Crwth: Reiss Engelhorn Museum, Mannheim, Andreas Praefcke (photographer), Public Domain

- The Magazine Fort (Phoenix Park, Dubiln): © Dronepicr (drone photographer), Creative Commons License

- The Magazine Fort (Powder Magazine) and the Star Fort (The Fortification): John Rocque (cartographer), A Survey of the City, Harbour, Bay and Environs of Dublin on the same Scale as those of London, Paris & Rome, Dublin (1757), Public Domain

- Coffin Bell: Halloween Prop, The Haunted Borough, Marlborough, MA, © Dave & Nancy Adams, Fair Use

- Safety Coffin: Life-Preserving Coffin in Doubtful Cases of Actual Death, Christian Henry Eisenbrandt (designer), Baltimore, MD, Public Domain

Useful Resources

- Joyce Tools

- FWEET

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- Annotated Finnegans Wake (with Wakepedia)

- From Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay

- Wake in Progress

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog

- One Year in the Wake

- James Joyce: Online Notes

- Finnegans Wake 365

- A Manual for the Advanced Study of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake