/ Little dictionary of Spanish film / part I

This 'little dictionary' consists of a brief historical review of Spanish film, a note of the most important Spanish directors and films chosen for their artistic value or historical significance.

SPAIN

The first public film screening took place in Madrid on 15th, 1896, and the same year began shooting of a short-length documentary footage. The most important filmmakers of the early period of Spanish cinematography are Fructuós Gelabert, who is probably the first one to play feature films in Spain, followed by the pioneer animation Segundo de Chomón y Ruiz and Ricardo De Baños. The first great international achievement of Spanish film was The Blasphemous Village of Floriana Rey, and the most famous filmmaker of Spanish origin Luis Buñuel, who most of the opus made in Mexico and France, made the Spain's suggestive documentary film Las Hurdres.

During the 1960's a series of co-productions were made in Spain (along with the Hollywood spectacles filmed in Spain, the movie Chimes of Midnight, directed by Orson Welles, who has recorded a peculiar version of Don Quixote in Spain for a number of years), is developing a production of so-called " spaghetti-western (in the Spanish version called paella-vesterni), several films directed by Italian director Marco Ferreri, then there was directors of the so-called " Barcellon School, marked by aestheticism, that begins with several prominent directors such as José Luis Borau, Vicente Aranda, Mario Camús and Carlos Saura, who in the last years of Franc's reigns directed more explicit social-critical films, and on two occasions (1961 and 1970) returns Buñuel returns to Spain. In this period, two of Spain's most prominent actors have successful international career: Fernando Rey and Francisco Rabal. After Franco's death (1975) and the gradual democratization of society, a series of films reviving and deconstructing the Franciscan period is emerging. The dominant theme of Spanish film since then has been critical to patriarchal and conservative structures in general, since the 1980's has been particularly influential in the motives of sexual frustration and neurosis and black-humorous components. Along with the veterans of Berlang and Bardem and Aranda, Camus and Saura, the most prominent Spanish director until the mid-1980s, Victor Erice and Pilar Miró are distinguished during the first postfranchistic decade.

From the beginning of the 1980s, Imanol Uribe is prominent in a series of provocative social-critical films of Basque theme, José Luis Garcia, whose film Volver a empezar, was the first Spanish film to be awarded for Oscar for Foreign Film (1982), Pedro Almodóvar, the most prominent and internationally most successful Spanish director since mid- 80' and Juan José Bigas Luna, Fernando Trueba, Julio Medem, Alex de la Iglesia, Santiago Segura , Alejandro Amenábar.

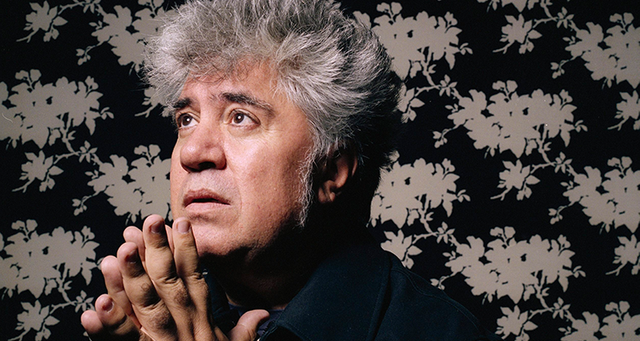

Almodóvar, Pedro

(Calzada de Calatrava, 25. IX. 1949).

Pedro Almodóvar is the cultural symbol par excellence of the restoration of democracy in Spain after nearly 40 years of the right-wing military dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Since Almodóvar’s emergence as a transgressive underground cineaste in the late 1970s and early 1980she has gone on to establish himself as the country’s most important filmmaker and a major figure on the stage of world cinema.

However, it is Almodóvar’s ambivalent relationship with the country of his birth (and where he has made all of his 16 feature films to date) that has proved symptomatic of the complexities surrounding the filmmaker. While subversion of identity is the key subject matter of his cinema, Almodóvar has consistently flirted with his own sense of “Spanish-ness” (most frequently in his recourse to – and resignifying of – the symbolism of the Catholic Church). This has led often to a mixed domestic reception, which takes the form of unconditional acclaim by certain sections of the Spanish media but that has also seen him vilified by conservative critics. Whatever reaction he provokes, there is little doubt that Almodóvar rarely – if ever – inspires indifference.

Almodóvar’s career has been plagued by accusations of frivolity. His apparent lack of political commitment contrasted with that of his contemporaries. The end of the dictatorship opened up a dizzying array of political, social and cultural opportunities and the possibility of substantive changes in society seemed real. Just across the border in Portugal – a few hours drive from Madrid – the 1974 revolution had provided what for some was an exemplary means of transforming society. By the same token, the dominant oppositional school of Spanish filmmaking – drawn, with very few exceptions, from the privileged elites – looked towards France and the auteuristtradition and which, in spite of its claims to committed film often seemed devoted to the cinematic essay. Almodóvar’s disavowal of this kind of solemnity would initiate a conflict with the Spanish film establishment that endures to this day, in spite of his international reputation.

Despite the hostility to which he has often been subject at home, Almodóvar has clearly emerged from a particularly Spanish cultural tradition. Much of the criticism that has been levelled at him stems from the alleged influence of Hollywood cinema on his films. Such critics often adopt the discourse of progressive politics – the accusation against Almodóvar is that he has capitulated to cultural imperialism – to defend what is essentially a fairly tiresome and well-worn brand of Spanish nationalism. The reality is that Almodóvar is indeed influenced by North American cinema (which international filmmaker isn’t?) and particularly so in his early work. This influence, however, is scarcely that of “dominant” Hollywood films but rather the underground, transgressive cinema of the early John Waters and Andy Warhol. That said, his numerous stylistic appropriations of Alfred Hitchcock (particularly in Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios, but there are many more) and the influence of Douglas Sirk’s melodramas are undeniable elements present in Almodóvar’s work, as he himself is keen to acknowledge. Likewise, his use of music – and the scores to his films are remarkable in their own right – suggests both a global sensibility and an ear for the newest trends close to home. From the post-punk new wave of his early movies to the boleros, the bossa nova and the flamenco of his melodramas and more mature work, Almodóvar’s cinema provides a veritable feast of transnational eclecticism.

Bigas Luna, Juan José

(Barcelona, 19. III. 1946).

Bigas Luna, an iconoclastic film director who emerged after the Franco dictatorship to portray the new Spain as engagingly and perplexingly robust and later discovered the stars Penélope Cruz and Javier Bardem.

Mr. Luna was part of a crop of filmmakers who blossomed after Franco’s death in 1975, reviving a long-dormant cinematic scene. His work, which was influenced by Surrealist artists, including his friend Salvador Dalí, drew attention for its broad social commentary, particularly its outlandishly inventive treatment of sexual relations in liberated Spain.

His most successful movie was “Jamon Jamon,” whose title translates as “Ham Ham.” Released in most European countries and the United States in 1992, it won a Silver Lion award at the Venice Film Festival and introduced Ms. Cruz to movie audiences. After seeing her performance, the director Pedro Almodóvar went on to cast her in many of his films.

“Jamon Jamon” tells a complicated intergenerational tale of sexual mores set in a small town. The title comes from the hams that hang ubiquitously in Spanish homes, restaurants and storefronts. Roger Ebert, writing in The Chicago Sun-Times, called it “a throwback to the days when directors took crazy chances, counting on their audience to keep up with them.”

In one scene, Ms. Cruz’s character imitates a cawing bird, taunting a parrot with its favorite word: penis. The film takes place under the shadow of one of the many enormous bull silhouettes that once advertised sherry, but now, stripped of signage, have become a Spanish folk tradition. In a dramatic moment, the giant fake bull is castrated.

Mr. Luna called the movie “a portrait of everything I like, love and hate about Spain.”

Mr. Luna’s great gift was to infuse storytelling with profound irony and dashes of magic. He made “Chambermaid on the Titanic” in 1997, the same year James Cameron made his epic “Titanic.” Mr. Luna’s film told the story of a French foundry worker who wins a contest. First prize is a round-trip ticket to Southampton, England, to witness the great ship’s maiden voyage.

He ends up allowing a Titanic chambermaid to sleep in his hotel room because the hotels are full. He resists her sexual advances but has erotic dreams that he comes to believe are true and, over time, flagrantly embellishes.The worker ends up going onstage to tell his sexy tale.

The film’s message was one Mr. Luna delivered many times and in many ways: Grand passion is rooted in fantasy.

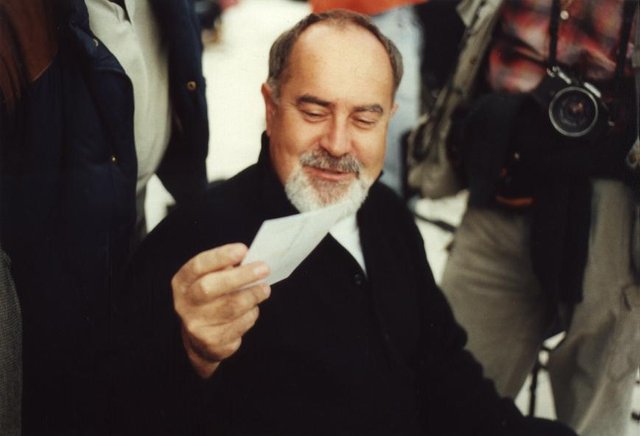

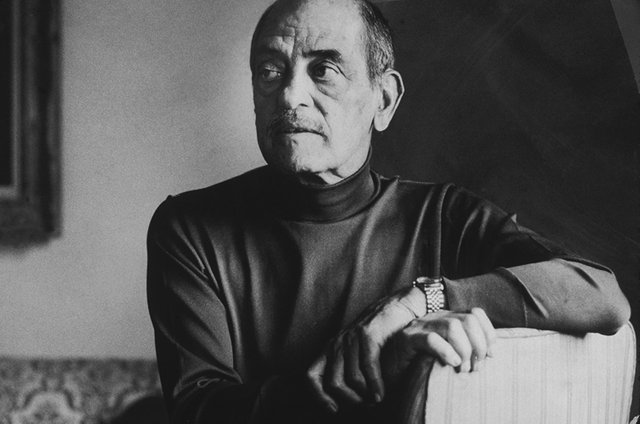

Buńuel, Luis

(Calanda, 22. II. 1900 — Ciudad de México, 29. VII. 1983).

Luis Buñuel was a singular figure in world cinema, and a consecrated auteur from the start. Born almost with cinema itself, his work moves from surrealist experimentation in the 1920s, through commercial comedies and melodrama in the 1950s, to postmodernist cine d’art in the 1960s and ’70s. Claimed for France, where he made his celebrated early and late films, for Spain, where he was born and had his deepest cultural roots, and for Mexico, where he became a citizen and made 20 films, he has more recently been seen as a figure in permanent exile who problematises the very idea of the national in his films.

A surrealist, an iconoclast, a contrarian and provocateur, Buñuel claimed that his project was to pierce the self-assurance of the powerful. His work takes shape beneath the “double arches of beauty and rebellion”, as Octavio Paz put it. Recently, his sons have reasserted Buñuel’s view of Un Chien andalou, as “a call to murder” against the “museum-ifying” of the celebrations of his centenary. While this exaggerates somewhat his radicalism and outsider status, there is considerable consistency in his attacks on the bourgeoisie, whose hypocrisy and dissembling both amused and enraged him. “In a world as badly made as ours,” he said, “there is only one road – rebellion.”

Buñuel is in fact satirising his own class, to which he comfortably and unabashedly belonged. He understood the neuroses and pettiness of his middle class Catholic upbringing well. “I am still an atheist, thank God”, he famously said. It is one of his many paradoxes: he was both inside and outside.

The bourgeoisie interested him particularly because its good manners demand the repression of desire. His readings of Freud inspired him to study his class as a laboratory for the twisted return of the repressed. But it was the social and economic power of the bourgeoisie that made him want to implode it from within. If Henry Miller was right when he stated that “Buñuel, like an entomologist, has studied what we call love in order to expose beneath the ideology, mythology, platitudes and phraseologies the complete and bloody machinery of sex,” Luis was also, like an entomologist, interested in the relationships of power in sex, politics and everyday life; not just the mating dance, but the dance of homosocial power disguised beneath it, and all the other forms of power that can be exercised as violence and more subtle forms of repression.

More than other directors, Buñuel has etched indelible images into film culture. The “Buñuelian” can refer to shots of insects, a sheep or other farm animal appearing in posh settings, cutaways to animals eating one another, bizarre hands, odd physical types and, especially, fetishistic shots of feet and legs (said Hitchcock of Tristana: “That leg! That leg!”). The term also implies the confusions of dream and reality, form and anti-form, an irreverent sense of humour, black, morbid jokes that hint at the constant presence of the irrational, the absurdity of human actions. Buñuel shares this sensibility with the Spanish esperpento, the distancing black comedy that has been considered an authentic Spanish film tradition.

Miró, Pilar

(Madrid, 20. IV. 1940 — Madrid, 19. X. 1997).

Pilar Miro Romero is a pioneering female director of movies and television who also fostered Spain's film industry by introducing state aid for promising young filmmakers when she served in the Socialist Government of the 1980's.

Born on April 20, 1940, in Madrid, Ms. Miro studied law at the University of Madrid but switched her interest to cinema and began working at state television in 1960. Ms. Miro, who became the first woman to direct dramas for Spanish television in 1966, was known for her link to progressive causes like the fight against racism. She won respect even from many leading conservatives, who attended her funeral today.

Outside of Spain, Miró remains best-known for her internationally acclaimed sophomore feature, The Cuenca Crime (1971). A graphically violent look at how the Civil Guard tortured victims earlier in the century, the film generated great controversy and was initially banned in a recently democratized Spain. However, authorities did allow Miró's film to represent Spain in the 1980 Berlin Film Festival; that year it won awards at other international festivals.

When it finally opened, it was a top box office attraction

In 1982, she was a media adviser to Felipe Gonzalez when he was elected for the first time as Prime Minister, starting nearly 14 years of Socialist Party rule. Ms. Miro served in his administration, first in the Culture Ministry, then as Director General of state television and radio. She resigned from that post in 1989 during a controversy over her spending some $30,000 in Government funds for her personal wardrobe. She paid back the money and was cleared of wrongdoing by a court in 1992.

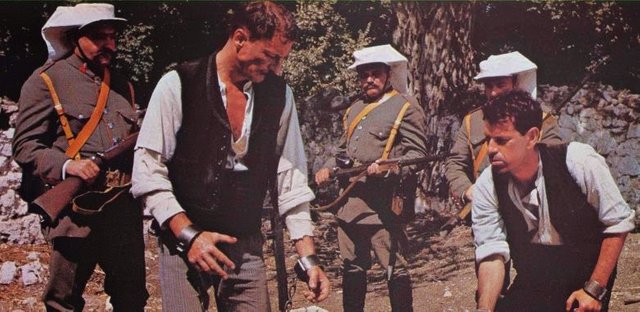

Saura, Carlos

(Huesca, 4. I. 1932).

A child of the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath, writer-director Carlos Saura flowered during the waning years of Franco's dictatorship, dodging the aging regime's censorship by leading his films into allegory, dreams and symbolism. His features exploring fascism's repressive effects on society became portraits of Spain in a dark mirror, poignantly expressing the country's uneasy relationship with its past.

While attending Madrid's Instituto de Investigaciones y Experiencas Cinematográficas (now known as the Escuela Oficial de Cinematografía), Saura and his peers were greatly influenced by Italian Neorealism, as evidenced by Saura's graduation short, La Tarde del Domingo/Sunday Afternoon (1957). Saura became a professor and taught film direction at the Escuela Oficial until 1963. In 1958, Saura released his color documentary Cuenca, followed by his debut fictional feature Las Golfos, which, though completed in 1959, was censored until the early '60s. The story of street hoodlums striving to escape their poverty by becoming bullfighters, it utilized a non-professional cast and was the first Spanish film shot entirely on location. Three years later, Saura made his second feature, Llanto por un Bandido/Lament for a Bandit (1964), a Spanish-French co-production about a famous Andalusian bandit. Though Saura wanted it to be a realistic account of the robber's life, the producers insisted on making it a swashbuckling epic. The resulting compromise was not only censored, it was a box-office failure and led Saura to eschew creative input from external sources on future projects.

Recognizing Saura's talent and vision, producer Elías Querejeta respected the director's need for absolute creative control and produced many of Saura's subsequent films, beginning with La Caza/The Hunt (1965), a powerful psychological thriller which commented on the societal effects of Franco's ideology. By the mid-'60s, Saura started organizing his longtime production team, including cinematographer Luis Caudrado, film editor Pablo G. del Amo, and American actress Geraldine Chaplin, with whom he would have a long-term personal relationship and a child. La Caza earned high praise at several prominent international film festivals, including the Berlin Film Festival where it received the prestigious Silver Bear award. Saura won another Silver Bear in 1968 with Peppermint Frappé, a dark exploration of how church-and state-enforced societal, sexual, and psychological repression can lead good people to monstrous deeds. While Saura's criticism of Franco was initially fairly subtle, his views became more obvious with time, but the more censors trimmed Saura's work, the more outspoken he became. The Spanish government was more tolerant of Saura than they might otherwise have been (he was never banned from filmmaking) because his films earned Spanish cinema so much international acclaim at festivals. However, on one occasion, the Ministry of Information released a particularly inflammatory Saura film, El Jardín de las Delicias/The Garden of Delights (1970), which castigated the government, the church, and the sexually repressed Spanish society, because they considered it too boring to pose a threat. The ministers' opinions notwithstanding, the story of a governess who is assaulted by three brothers (each representing the aforementioned problems) had particular impact for non-Spanish audiences.

Franco died in 1975, and with the fall of his regime came a new freedom in expression. Still, Saura remained haunted by his childhood experiences and the dark aspects of Spain's 20th century history. From this point, his films have alternated between those which focus upon sociopolitical issues and less polemic "art house" film

NOTE

-The first few paragraphs were my tranaslation from croatian article ''Mali Leksikon Španskog Filma''

-Biography of Almadovar and Bunuel are taken from Senses of Cinema

-Biography of Bigas Luna is taken from New Your Times article

wow

you've made such a wonderful research wooow good job, brilliant!