Should You Pay For Storage With Filecoin? Probably Not.

Filecoin raised more than $200m in an Initial Coin Offering, on the promise of building a decentralized network for buying and selling file storage.

Key Takeaways:

- Filecoin is a blockchain network in development, where “proof of work” is replaced with “proof of storage”.

- Filecoin’s focus on mining attacks and decentralization makes it an inefficient replacement for cloud-based object storage.

- If Filecoin is really going to be a “useful” token, its economics must ultimately be driven by that use, not by hype around Bitcoin and ICOs.

What is Filecoin?

Protocol Labs is in the process of designing and implementing a new blockchain network, called Filecoin. In their words:

Filecoin is a decentralized storage network that turns cloud storage into an algorithmic market.

The market runs on a blockchain with a native protocol token (also called “Filecoin”), which miners

earn by providing storage to clients. Conversely, clients spend Filecoin hiring miners to store or distribute data.

Filecoin has attracted a lot of attention due to the amount of money it has raised for development, and the novel mechanism by which Protocol Labs has done so. The Simple Agreement for Future Tokens is an investment agreement by which qualified investors pre-purchased Filecoin tokens. Unlike other recent “initial coin offerings” (ICOs), Filecoin investors will not receive their tokens until the software is ready to use. Protocol Labs announced at the conclusion of their token sale that they had raised more than $200 million to fund the development of Filecoin.

While the Filecoin protocol is still under development, its outline was laid out in Protocol Labs’ white paper. The key parts are (1) a “proof of replication” and “proof of space-time” design which allows participants to prove that they are contributing storage to the Filecoin network; (2) a distributed election protocol weighted by storage to determine who will create the next block, and get mining rewards; and (3) public marketplaces for storage and retrieval of data.

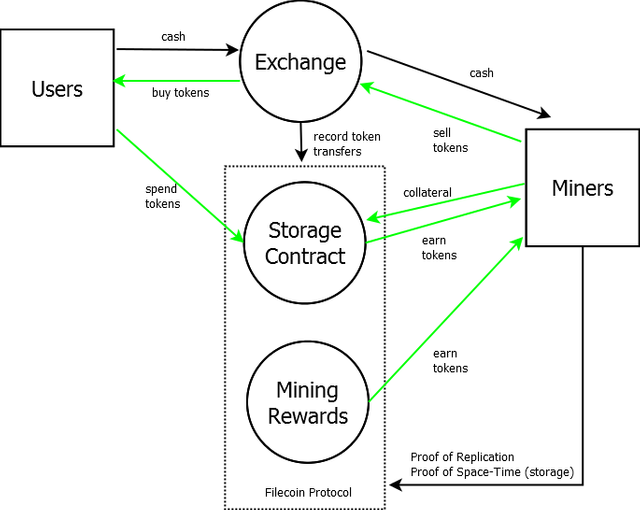

People and organizations that which to use Filecoin must first purchase some Filecoin tokens from an exchange (or earn them by participating in the Filecoin network.) They can then insert “bid” offers specifying how much Filecoin they will pay to store a given amount of data, for how long. The bid also asks for an amount of Filecoin to be pledged as “collateral” if the data is lost. These bids are matched with storage miners who submit “ask” orders specifying their price and available storage.

When a bid and ask are matched, a record is placed in the blockchain ledger, and the data is transferred out-of-chain using a peer-to-peer protocol (IPFS, the “InterPlanetary File System”.) Both the buyer’s payment and the seller’s collateral are held until the duration of the storage bid has expired. Then the seller receives the amount of Filecoin specified in the original bid, from the buyer’s account. During the term of this contract, the seller must periodically prove that they still hold the data, using a publicly-verifiable cryptographic proof. Sellers who cannot satisfy this proof will lose their collateral, and the data must be retrieved from a different copy. Usually a buyer should use an erasure codingc in which the data is spread across multiple sellers.

If the buyer wishes to retrieve the stored data, they submit bids to a “retrieval” market, and the winning seller provides the data in small chunks, each of which is paid for with a small Filecoin transaction, in some way not yet designed (because on-blockchain payments would be far too slow.) Nothing prohibits somebody other than the original storage winner from taking the retrieval contract--- if they can provide the correct data.

Filecoin as a Cloud Storage Replacement

Cloud object storage like Amazon S3 has multiple uses: as a content distribution network, as back-end for a cloud-native application, as bulk storage for large data sets, or as backup. Only the last two of these fit the Filecoin model well, and backups are the best fit when they have a well-defined retention period.

Filecoin is not a CDN, although a CDN could in theory be built on top of it. The use of a specialized protocol (rather than HTTP) and the online payments for retrieval make this a poor fit. Using Amazon S3 to distribute large files works because payment is aggregated, and charged to the content owner, not the downloader. It also provides a standard browser-supported protocol, and fine-grain access controls.

Filecoin’s on-blockchain bid/ask market and high cost of updating content make it unsuitable for storing objects in real time, as would be required by a cloud-native application currently using S3 or Openstack Ceph. In order to participate in the “proof of replication”, a storage miner must compute time-intensive cryptographic operations on each new object stored.

For very large data sets with unknown lifetimes, Filecoin’s model seems difficult to implement. There is no facility (yet) for renewing storage contracts, or cancelling them early. A potential customer with a large database of geolocation information, or register data used for data mining, or other big data applications would find it challenging to operate at scale. Getting large amounts of data into Amazon S3 is no trivial task--- Amazon even provides services where data can be shipped on physical devices! Even if the storage network, in the aggregate, has plenty of network throughput available, the purchaser of storage is still limited by their own network connection. This expensive round-trip would have to be repeated on every expiration of a storage contract. Most likely such large databases would have to be divided into many small storage objects which could be rotated among miners on a continuous basis. This would produce a constant and nontrivial need for the operator to interact with Filecoin and with Filecoin miners, instead of simply “outsourcing” storage to the cloud.

Backup of application data seems the ideal fit for Filecoin. Most backups are written once and never read, and a backup frequently comes with an explicit retention period which can be matched to a Filecoin bid.

However, there is reason to question whether Filecoin could ever be an efficient replacement for cloud object storage even in this use case. While the economics will be discussed in the next section, the technical obstacle facing a potential Filecoin user is how to ensure the desired level of redundancy.

Filecoin miners are pseudonymous; the same physical infrastructure could be represented as many different identities on the Filecoin network. The designers at Protocol Labs are well aware of this possibility, and their protocol goes to great lengths to prevent “Sybil attacks” and “Generative attacks” in which storage miners claim a large amount of physical storage, but deduplicate or compress data in their own implementation. The protocol must prohibit such efficiencies, because they could be used to take over control of the generation of new blocks by claiming absurdly large amounts of storage. (Of course, end users of Filecoin could still implement compression and deduplication at a higher layer, similar to how Tintri’s Cloud Connector provides deduped and compressed storage on Amazon S3.)

The proposed mechanism requires newly written objects to be “sealed” by the storage miner, creating a cryptographically-secured copy that is demonstrably unique. The cryptographic operations are tuned so that it takes detectably longer to generate a block and seal it on demand, than to reply to a proof request for a block which has already been sealed. The impact of this operation on storage cost can be nontrivial, but it achieves the protocol designer’s goal of requiring a miner to be honest about the amount of storage consumed.

Unfortunately, this goal is not the same as the storage buyer’s goal, which is to ensure data resides in independent failure domains. It makes no sense to have four copies of your data if all the copies reside in a data center vulnerable to the same flood. Filecoin cannot even prove that the four copies do not all reside on the same disk, just that there are in fact four copies. (In conventional cloud storage such as Amazon S3, the client can store data explicitly in different regions.)

Perhaps with enough decentralization of storage capacity, this risk will be small. Previous blockchain networks, though, often show concerning levels of mining power. A new entrant to the network may be motivated to offer low prices via a variety of pseudonyms in order to start earning on their investment, so storage bids that occur close in time could all be captured by the same physical provider, even though mining power in the large is distributed. That is, the ask market may be concentrated at any given point in time, even if the storage market as a whole is not.

Filecoin as Cost-Efficient Storage

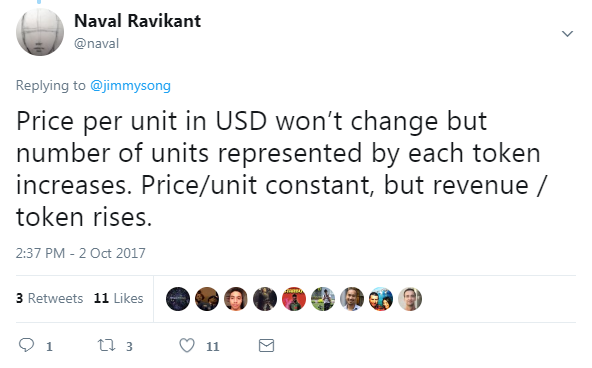

Coverage of Filecoin and its ICO often repeats two key themes: (1) storage is cheap and Amazon’s cost is high, and (2) the value of the network as it grows will increase the value of Filecoin tokens. The former often quotes the price of a large-capacity hard drive, while the latter looks like the following:

The price per unit of bulk storage has certainly not stayed constant, and it is likely to continue its decline. If Amazon is the competition for Filecoin, look at Amazon’s prices over the past decade:

| Date | Amazon price ($/GB/Month) |

|---|---|

| 1/11/2008 | $0.150 |

| 1/11/2010 | $0.140 |

| 1/12/2012 | $0.095 |

| 1/4/2014 | $0.030 |

| 1/12/2016 | $0.023 |

The least that the price has gone down since 2010 has been been a 23% drop over two years. Should this trend continue, we would expect $0.017/GB/month next year, and $0.013/GB/month two years after that. The current price for Amazon’s “infrequent” storage, which might be a more apt comparison, is about half as much, and “Glacier” storage is currently just $0.004/GB/month.

A low-end 8TB hard drive costs about $170. That amount of storage from Amazon S3 would cost $184/month, or $32/month for Glacier storage. While that shouldn’t be the end of cost/benefit analysis, because there are several operational costs to consider, it seems plausible that the cost of storage on the Filecoin network could be lower than what Amazon charges (though, as we will explore in the final section, this does not necessarily mean a healthy market for storage.)

It is less clear that increase in size of the Filecoin network will of necessity lead to increase in Filecoin token value. The immediate value provided by spending Filecoin tokens is clear and can be compared to alternatives such as Amazon S3. We can analyze the cash flow through Filecoin using this as our foundation, if we ignore purely speculative trades.

If in a given month there is “S” TB of storage available, at a price of “P” dollars per TB per month, then the value of Filecoin tokens that are sold by miners and purchased by storage consumers must be S times P. That value (in dollars) must equal the quantity of tokens sold Q multiplied by the average price per token T. (Tokens cannot be used simultaneously to support more than one storage contract; a token is essentially “locked down” for the entire length of the contract.)

For example, if there is 3000 TB of storage in use, at $0.004 per GB per month, then $12,000 must change hands each month. If there are 10,000 tokens “floating” for sale on the exchanges (rather than being held as speculative investments) then the average price paid must be $1.20 per token.

From the equation SP=QT we can look at how rates of change in one of the quantities must affect the others. While the number of tokens is ultimately fixed, no blockchain with this property has yet hit its limit, so for the foreseeable future we should expect the number of tokens to grow, as they are given out as mining rewards. (It is not clear whether more established blockchains, like Bitcoin, will successfully make the transition from mining rewards to purely transaction fees.) Tokens held for long-term investment will also slowly enter the market.

The amount of storage in the Filecoin network can be expected to grow as storage capacity gets larger, and more individuals and organizations become storage miners. However, the price of storage should go down, both through improvements in technology and through competition as more miners compete for the same addressable market.

The price per unit storage should go down at least as much as Amazon S3’s 25% per two years. But raw price per GB of hard drive has historically halved roughly every 14 months. We can explore a range of such possibilities:

| Example Scenarios | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage price decrease (per year) | 12.50% | 40.00% | 40.00% | 12.50% |

| Filecoin storage growth | 100% | 100% | 100% | 25% |

| Filecoin token float increase | 10% | 10% | 25% | 10% |

| Filecoin token value | 59.09% | 9.09% | -4.00% | -0.57% |

It is not hard to come up with plausible values where the Filecoin token value is flat, or even decreasing, year over year.

The separation between "value of the network or business" and "value of the token" is explored in much more detail in this Medium post, which I recommend: https://medium.com/@anshumanmehta/futility-tokens-6b8283c977a9

The Distorting Effects of Mining, Speculation, and Deflation

The preceding fundamental analysis ignored speculative investment. The number of tokens used for actual payment for storage may be dwarfed by the speculative interest in Filecoin tokens. Also, the presence of mining rewards can distort the market in strange ways. These factors can reduce the attractiveness of Filecoin as a storage mechanism, even though it is good news for the raw cost of Filecoin storage as measured by cost per GB per month.

When miners are primarily motivated by the market value of mining rewards, rather than the value of storage contracts, they will seek to increase the number of Filecoin awards. In Bitcoin you can find blocks that have been mined which are empty rather than containing any transactions, because the miner made the determination that it was not worth pursuing the transaction fees. For Filecoin this dynamic does not exist, but the mining rewards accrue to those with the most committed storage. This should lead to very, very low ask prices as the actual value of the contract is irrelevant. Miners may in fact be motivated to sell storage to themselves to avoid the network costs of actually sending or retrieving large amounts of data. This could lead to a paradox in which plenty of transactions occur yet very little useful data is stored.

In fact, a buyer who needs storage may find very little storage on offer in the marketplace, if prices are low enough. This is because Filecoin (as currently specified) awards mining power to those with space allocations (orders), not merely space in bids. But if mining rewards dominate, miners are incentivized to have all of their space in-use, even if they have to generate their own orders to fill it. Suppose mining rewards are $10,000 per block, and the Filecoin network contains 100 petabytes of storage. A miner who leaves 8TB of capacity empty loses an expected value of about $0.80 per Filecoin block. But the absolute most the miner could hope to gain from selling to a legitimate buyer is $184/month, by comparison with the Amazon S3 price. If the space, at that price, can be expected to remain empty for more than 230 blocks per month, leaving it available is a net loss for the miner. (Bitcoin blocks are regulated to occur once every 10 minutes; for Filecoin this mechanism has not yet been specified, but an equivalent rate would mean 230 blocks are generated in 1.6 days.) If prices are low and mining rewards are large, miners have no incentive to maintain “liquidity” by keeping ask offers in the order book.

Even absent self-dealing (or if some method is come up to prevent it), speculative increases in value may also give potential purchasers pause. Deflationary currencies have not historically led to healthy marketplaces. If somebody who holds Filecoin can expect an $X increase in value by holding their tokens until later, it makes sense to spend up to $X on Amazon S3 storage in the intervening period, instead of spending the Filecoin. A purchaser may also worry about whether the future retrieval market will provide attractive prices, or have difficulty predicting the correct amount of Filecoin to purchase.

On the other side of the transaction, large negative price swings may cause miners to engage in strategic default. If the value of continuing a current contract is $10, with $1 of collateral at stake, but the same amount of storage would fetch $15 on the current open market, it makes economic sense for the miner to abandon their current contract and re-sell the storage to a higher bidder. The repair mechanism may not be able to successfully re-bid the contract at its original Filecoin price.

In order for Filecoin to be a success as a storage mechanism, and not just a cryptocurrency, it must provide stable, predictable prices. This requires a market driven by the fundamentals of storage cost, not by mining rewards or speculative frenzy. Filecoin must also solve the problem of providing purchasers the same confidence in redundancy and availability that they achieve by using existing cloud service providers for storage.

The Filecoin whitepaper can be found at https://filecoin.io/filecoin.pdf

It is a good time to update those numbers (:

outstanding piece. thank you