Succoth - Station No 2

In Numbers 33, the itinerary of the House of Israel between the Exodus from Egypt and the Conquest of Canaan has been recorded in a catalogue of the Forty-Two Stations of the Exodus. In an earlier article in this series, I concluded that the first station, Rameses, referred to the area around the Hyksos city of Avaris, on the site of which the later city of Per-Rameses was constructed. Numbers 33 continues:

And the children of Israel removed from Rameses, and pitched in Succoth. (Numbers 33:5)

Succoth has already been mentioned in the Bible:

And the children of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Succoth, about six hundred thousand on foot that were men, beside children ... And they took their journey from Succoth, and encamped in Etham, in the edge of the wilderness. (Exodus 12:37 ... Exodus 13:20)

Where was Succoth? In the Jewish Study Bible, we are told:

Succoth was the name of both a place and a region in the eastern Nile delta, in or near the land of Goshen where the Israelites lived ... An Egyptian letter from the period of Pharaoh Seti II ... indicates that the place Succoth was one day’s journey from the palace, which was presumably in Rameses. (Berlin & Brettler 129)

It has long been surmised that succoth is a Semitic word, not an Ancient Egyptian one. In another article in this series—The Stations of the Exodus—I quoted St Jerome on this very subject:

4. The people of Israel setting out from Rameses, pitched camp at Succoth. The second station. In this they bake unleavened breads and first pitch their tents, whence the place takes its name. Succoth indeed is translated into our [Latin] language as tabernacula or tentoria [tents]. And on the fifteenth day of the seventh month, the Feast of Tents is celebrated. (Jerome §4)

Succoth is the plural of a Hebrew term that may be translated as tents, tabernacles or booths. In James Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, it is Number 5523. In the accompanying Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, Strong traced it back to a primitive Semitic root meaning to entwine :

5523 סֻכֹּת C̨ukkôth, sook-kohthʹ; plur. of 5521; booths; Succoth, the name of a place in Egypt and of three in [Palestine]:—Succoth.

5521 סֻכָּה c̨ukkâh, sook-kawʹ; fem. of 5520; a hut or lair:—booth, cottage, covert, pavilion, tabernacle, tent.

5520 סֹךְ c̨ôk, soke; from 5526; a hut (as of entwined boughs); also a lair:—covert, den, pavilion, tabernacle.

5526 סָכַךְ c̨âkak, saw-kakʹ; orשָֹכַךְ sâkak (Exod. 33:22) _saw-kakʹ ... a [primitive] root; [probably] to entwine as screen; by [implication] to fence in, cover over, ([figuratively]) protect:—cover, defence, defend, hedge in, join together, set, shut up. (Strong 82)

It is easy to see why many early commentators deduced from this that Succoth was so called because the Israelites had pitched their tents there at the end of the first day’s march out of Egypt. Take for example Adam Clarke’s Commentary on the Holy Bible, the first volume of which appeared in 1810:

As the term Succoth signifies booths or tents, it is probable that this place was so named from its being the place of the first encampment of the Israelites. (Clarke 355)

But this explanation of how Succoth acquired its name is now generally set aside in favour of an alternative etymology. In 1880, the German Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch wrote:

To the east of the Tanaitic nome, or the “Eastern border land,” another nome was situated on the sandy banks of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile, the eighth in the general enumeration of the Egyptian nomes, which the inscriptions represent under the designation of the “point of the east.” The capital of the nome we have mentioned bore the name Pi-tom, that is, “the town of the sungod Tom,” in which we must immediately recognize the Pithom of the Bible. The town occupied a central situation of the district, whose name also must be referred to a foreign origin. It is the district Suko, or Sukot, the Succoth of the Holy Scriptures at the exodus of the children of Israel out of Egypt, the meaning of which, “tent,” or “tent camp,” can be only established by the help of the Semitic. Such a designation is not extraordinary for a district whose natural peculiarity quite answers to the meaning of the name, since it embraces places with meadows, the property of pharaoh, on which the wandering Bedouins of the eastern desert pitched their tents to afford necessary food for their cattle. Even as late as the Græco-Roman times of Egyptian history appears the designation “tents;” and tent-camp (Scenæ) is also applied to places where they were accustomed to pitch their camp of tents. (Brugsch 1880:67-68)

The tents after which Succoth was named were not the tents of the fleeing Israelites but those of the Arabian Bedouin, who had been permitted to dwell on the eastern borders of the Delta during the summer months, when the Sinai Desert was too hot and dry for their grazing herds.

But did the Egyptians really borrow the name from the Semites, or was it the other way round? The Swiss archaeologist Henri Édouard Naville believed that the Biblical Succoth was a transliteration of a native Egyptian name Thukut and that its Hebrew meaning of tents was just a coincidence:

M. Brugsch, in his extensive researches on the Geography of Egypt, first drew the attention of Egyptologists to the Hebrew word corresponding to Thuku or Thuket. The [hieroglyphic] letter W which was pronounced th, is often transcribed in Greek and Coptic by σ [sigma]; and in Hebrew by ס [samekh]. The name of Σεβέννυτος, Sebennytus, Theb neter ... is a striking proof of the truth of this assertion, which is corroborated by the spelling of many common names. I need not dwell on this philological demonstration, which seems to me quite conclusive. The transcription of Thukut would be the Hebrew סֻכּוֹת Succoth. It is not at all surprising that the Hebrew word should mean tents. We have here an example of what is called “popular etymology,” a philological accident which constantly occurs in mythology and geography. A name passing from a language to another keeps nearly the same sound and the same appearance, but it undergoes a change just sufficient to give it a sense in the language of the people who have adopted the word. The new sense may be totally different from the original (Naville 7)

Whether the name was originally Semitic or originally Egyptian is a moot point: what concerns us is the location of the Biblical Succoth. This too, however, is still matter of scholarly debate. And it is not helped by confusion over the geography of the ancient Egyptian political units known as nomes.

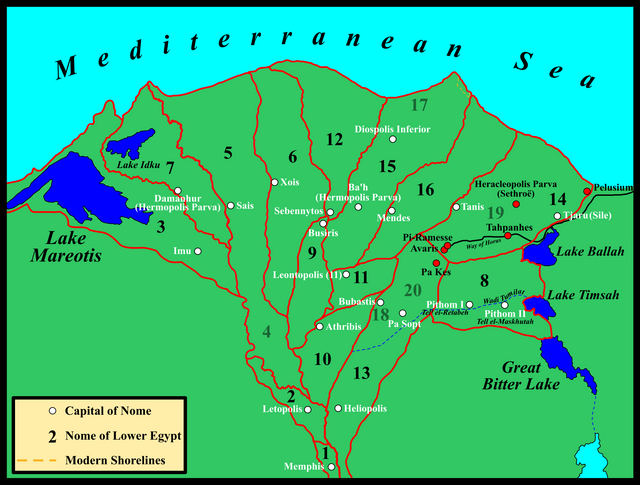

The Nomes of Lower Egypt

Since pre-Dynastic times, ancient Egypt was divided into administrative districts known by modern archaeologists as nomes—a term borrowed from the Classical Greek historians. Upper Egypt (the Nile Valley) was comprised of twenty-two nomes, and Lower Egypt (the Nile Delta) of twenty. But the number of nomes, as well as their borders and capital cities, changed over the long course of Egyptian history, particularly during the Graeco-Roman period (after 332 BCE). Anyone who attempts to research this subject has my sympathies. Every source seems to contradict every other source on one point or another. At times I despaired of making any sense of the situation. Finally, I came across a 1955 article by John A Wilson, an Egyptologist from the Oriental Institute, which shed some much needed light on this obscure corner of Egyptology:

Here it may be stated that L.E. 4 and 5 [Nomes 4 and 5 of Lower Egypt] once constituted a single nome, later divided into “southern” and “northern.” L.E. 7 and 8 are peripheral and bear similar names; they may have been added to an original list, with L.E. 8’s devotion to the [sun]god Atum is explained if the nome were a subdivision of L.E. 13 [whose capital was Heliopolis, the City of the Sun]. Similarly, L.E. 17 was added in the New Kingdom to the list of nomes, although appearing as the site of an ultima Thule in the Middle Kingdom. The pre-Ptolemaic lists show the order to be: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 10 12 15 16 13 14 17; that is, 1–7 down the western river, 8 added as comparable to 7, 9–12 and 15–16 down a central river, 13–14 down the eastern river, and 17 added as the youngest member. Finally, in Ptolemaic times, L.E. 18 and 20 were separated out of 13, and L.E. 19 was separated out of 14. The secondary nature of some of these nomes has geographic significance. (Wilson 230)

If we can trust this, then not all twenty nomes existed at the time of the Exodus, and the capitals of those that did exist may not have been the same as they were in later centuries. Nomes 18-20 did not yet exist, their territory being contained in Nomes 13 and 14. Tanis had not yet been founded, so it was certainly not the capital of any Tanitic nome.

Wilson’s analysis allows us to make some sense out of apparently contradictory accounts in the Classical historians. Take, for example, the prolonged and heated debate over the location of the Hyksos capital of Avaris. Josephus, quoting Manetho, wrote how the Hyksos king Salatis:

found in the Saite Nomos a city very proper for his purpose, and which lay upon the Bubastic channel [of the Nile], but with regard to a certain theologic notion was called Avaris. (Josephus, Against Apion 1:14)

Note that Josephus’s (or Manetho’s) placement of Avaris in the Saitic Nome is usually emended to Sethroitic:

In the Saite Nomos: Read in the Sethroite Nomos. For so Dr. Hudson rightly observes the text in Josephus should be corrected: from Syncellus, page 61. and from Ptolemy’s Geography, L. IV. For ’tis certain that Sais was situate not near the Bubastick, but the Sebenite channel of the Nile, and that Sethros, as here, was near the Bubastick channel. But concerning this entire, this invaluable fragment of Manetho’s, See Essay on the Old Testament Append. pag. 157.-159. and pag. 182.-188. and my Chronological Table: where all these things are digested in due order. (Whiston, footnote)

The Armenian edition of Josephus has Methraitic, which may be a corruption of Sethroitic (Kurtz 398).

And all of this makes some sort of sense. Avaris and Per-Ramesse were situated in the extreme south of the 14th nome, which at that time included the territory of the later 19th nome. The 14th nome was the Sethroitic, and the later 19th nome was the Tanitic. Now, some scholars have noted that Herodotus referred to the Tanitic branch of the Nile as the Saitic and that Strabo (Geography 17:1:20) explicitly pointed out that these two names were used interchangeably. These scholars would leave Josephus’s Saitic Nome alone, understanding this to mean Tanitic. But this too makes sense, because when the Hyksos ruled Egypt the Tanitic (19th) and Sethroitic (14th) nomes had not yet been broken into two. So Avaris was indeed in the Saitic, Tanitic and Sethroitic Nome!

Bearing all this in mind, we can now try to make sense of the researches of Brugsch, Naville and other scholars.

Brugsch’s Egyptian Geography

Brugsch first:

To the east of the Tanaitic nome [N19, still part of Sethroitic N14 during the Exodus], or the “Eastern border land,” another nome was situated on the sandy banks of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile, the eighth in the general enumeration of the Egyptian nomes, which the inscriptions represent under the designation of the “point of the east.” The capital of the nome we have mentioned bore the name Pi-tom, that is, “the town of the sungod Tom,” in which we must immediately recognize the Pithom of the Bible. The town occupied a central situation of the district, whose name also must be referred to a foreign origin. It is the district Suko, or Sukot, the Succoth of the Holy Scriptures ... (Brugsch 67)

... the vast mounds, near a modern town called Qous by the Copts and Faqous by the Arabs, remove all doubt as to the site of the ancient city of Phacoussa, Phacoussse, or Phacoussan, which, according to the Greek accounts, was regarded as the chief city of the Arabian nome [N20, still part of Heliopolitan N13 during the Exodus]. It is the same place to which the monumental lists have given the appellation of Gosem, a name easily recognized in that of “Guesem of Arabia,” used by the Septuagint version as the geographical translation of the famous Land of Goshen. Directly to the north, between the Arabian nome, with its capital Gosem, and the Mediterranean Sea, the monumental lists make known to us a district, the Egyptian name of which, “the point of the north,” [Tanitic N19, still part of Sethroitic N14 during the Exodus] indicates at once its northerly position. The Greek writers call it the Nomos Sethroites [N14], a word which seems to be derived from the appellation Set-ro-hatu, “the region of the river-mouths,” which the ancient Egyptians applied to this part of their country. While classical antiquity uses the name of Heracleopolis Parva to designate its chief town, the monumental lists cite the same place under the name of “Pitom,” with the addition, “in the country of Sukot.” Here we at once see two names of great importance, which occur in Holy Scripture under the same forms, the Pithom and the Succoth of the Hebrews. (Brugsch 207-208)

This is still a complete mess. In the first passage, Brugsch clearly identifies the Biblical Pithom with Pi-Tom, the capital city of the 8th Nome (“Point of the East”). In the second extract, however, he identifies the same Pitom|Pithom with Heracleopolis Parva in the Sethroitic Nome 14, which he calls “Point of the North”. Some of this confusion can be removed by applying what we learnt from Wilson: Sethroitic N14 (“Eastern Border Land”) and Tanitic N19 (“Point of the North”) were once joined together as a single nome, so Brugsch’s confusing of these two is understandable and, perhaps, even excusable. But there is no accounting for his identification of Heracleopolis Parva in the Sethroitic N14 with Pithom in N8. These two nomes were always separate and had different designations. N14 was, in Brugsch’s own translation, Eastern Border Land, while N8 was Point of the East.

One thing is clear, though: Brugsch located N8 to the east of Tanis, “on the sandy banks of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile”. This is not where modern Egyptologists place N8. They follow Édouard Naville and locate it on the Wadi Tumilat, about 50 km further south.

Naville’s Egyptian Geography

Édouard Naville was the archaeologist who first proposed Tell-el-Maskhutah in the Wadi Tumilat as the site of the city of Pithom. He also discovered that the district in which it lay was called by the ancient Egyptians Thuku:

If we consult the [geographical] lists, the most important of which are engraved on the basements of the walls of Denderah, Edfoo, and Philae, we find that the VIIIth nome of Lower Egypt is called [hieroglyph], a name which Brugsch reads nefer ab or ab nefer. The local god was Tum Harmachis, with the distinctive epithet of ... the living.

The capital of the nome bears the civil name of ... Thuk, Thuket, or Thukut .

The religious name is ... Ha Tum, the abode of Tum, the god of the nome, or the same written in the more frequent form ... Pi Tum, Pithom. When this city is mentioned there is generally added ... which is at the Eastern door.

The religious name of the city considered as the residence of its god thus consisted of the name of Tum, preceded by the word ... abode or house, and often followed by the determinative < ...

Besides the lists, and the texts of a purely geographical character, we find in the papyri several of the names belonging to the nome. The most frequent is ... Thuku, which occurs repeatedly in the letters of the scribes and officials of the XIXth dynasty, contained in the so-called Anastasi papyri. We see there that the name of Thuku has the determinative of a borderland inhabited by foreigners. It was under the rule of a ... lieutenant or wakeel. It contained a fortification called ... the skaïr of Thuku, or ... Khetem of Thuku, and what is more important, it contained Pithom, as we see from this sentence, to which we shall refer farther, the lakes of Pithom of Menephthes, which is of, or which belongs to, Thuku. It is clear from those inscriptions that before becoming the civil name of the capital, Thuku was the name of a region, a district which contained Pithom, and it had that meaning under the XIXth dynasty. (Naville 5-6)

The theory that the Biblical Succoth was the Egyptian Thuku in the Wadi Tumilat is still very popular. But if Brugsch is correct, then Pithom and Thukut lay further north, closer to Pelusium. Brugsch, as we have seen, identified Pithom with Heracleopolis Parva, which was the capital of the Sethroitic N14 in Classical times. In earlier times, however, the capital was Tjaru, or Sile, a fortress which lay about 20 km east of Heracleopolis Parva. It seems that Heracleopolis Parva did not exist at the time of the Exodus (Spencer 37-51). Either way, though, Pithom was the capital of N8, not N14. So, Brugsch cannot be right, can he?

Confusion

Brugsch’s geographical confusion has had consequences. In the article Succoth, in the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, C R Conder writes:

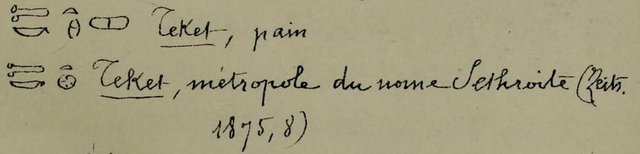

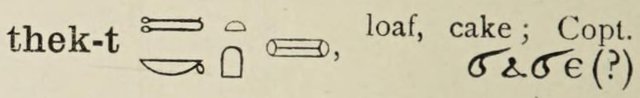

SUCCOTH(ṣukkōoth; Sokchṓth [Ex 12:37; 13:20; Nu 33:5]): The first station of the Hebrews on leaving Rameses (see Exodus). The word means “booths.” The distance from Etham (q. v.) suggests that the site may have lain in the lower part of Wâdy Tumeilât, but the exact position is unknown. This region seems possibly to have been called T-K-u by the Egyptians (see Pithom). Brugsch and other scholars suppose this term to have been changed to Succoth by the OT writer, but this is very doubtful, Succoth being a common Heb word, while T-K-u is Egyp. The Heb ṣ does not appear ever to be rendered by t in Egyp. The capital of the Sethroitic nome was called T-K-t (Pierret, Vocab. hiéroglyph., 697), and this word means “bread.” If the region of T-K-u was near this town, it would seem to have lain on the shore road from Edom to Zoan, in which case it could not be the Succoth of the Exodus. (Orr 2869)

When I first read this, I thought that there must have been two different places in ancient Egypt called T-K-u or T-K-t: one in the Wadi Tumilat in N8, and another further north in Sethroitic N14. Either could be the Biblical Succoth, the Second Station of the Exodus. Conder rejects the latter because it lay on “the shore road from Edom to Zoan”. Now, Edom was in southern Canaan, and Zoan was a Biblical name for Tanis, so this shore road is the Way of Horus, or the Way of the Philistines. It is explicitly stated in the Bible (Exodus 13:17) that the Israelites did not return to Canaan by this, the most direct, route. But it is my belief that when the Israelites first set out from Rameses, they did initially follow the Way of Horus, before turning south or southeast into Sinai. One day’s march from Avaris along the Way of Horus could very well have brought them close to either Heracleopolis Parva or Tjaru.

But, alas, there were not two places called T-K-t. They were both one and the same: the district in which Pithom lay. Conder regarded them as two separate places only because of Brugsch’s confusion between N8 and N14. In the passage I just quoted from the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Paul Pierret’s Vocabulaire Hiéroglyphique is cited in support of the name Teket. Here is what Pierret writes:

Teket, pain

Teket, métropole du nome Sethroite (Reits. 1875, 8)Teket, bread

Teket, capital city of the Sethroitic Nome (Zeits. 1875, 8)

(Pierret, 697, my translation)

But Pierret’s source for this nugget of information is none other than our old friend Heinrich Brugsch, whose article Geographica appeared in 1875 in the Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde [Journal of Egyptian Language and Archaeology]. Pierret’s Teket hieroglyph is vocalized and identified thus by Brugsch:

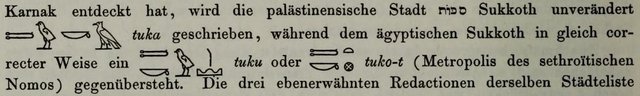

tuku oder ... tuko-t (Metropolis der sethroïtischen Nomos)

tuku or ... tuko-t (Capital city of the Sethroitic Nome)

(Brugsch 1875:8)

E A Wallis Budge has the first of these hieroglyphs—the one for bread—in his Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary (Budge 862), but I have not been able to find the other one.

This leaves an element of doubt hanging over the matter. When Brugsch reads them as the Egyptian name for the capital of the Sethroitic nome, he is referring to Heracleopolis Parva (Brugsch 1880:208). But he has simply confused or conflated N14 and N8, and his tuku or tuko-t is no different than Naville’s Thuku or Thuket. They both refer to the district in which the city of Pithom was built—wherever that was. The only point of disagreement between Brugsch and Naville is the location of this city: Brugsch located it at Heracleopolis Parva (Tell Bileim), while Naville located it at Tell el-Maskhutah.

Unfortunately, the location and identification of Pithom cannot be glossed over, even though it is not central to our quest. Pithom is mentioned in Exodus 1:11 as one of the store cities the Israelites built for the Egyptians, but it is not one of the Stations of the Exodus. It is possible that it did not actually exist at the time of the Exodus, and just as Avaris is referred to as Rameses, a later city built on the same spot as Avaris, so Pithom may refer to a Hyksos settlement that occupied the same place as the later city of Pithom. As we have seen, Naville identified Tell-el-Maskhutah with Pithom, and this is currently a popular theory among Egyptologists. Interestingly, the remains of a Hyksos fortress have been discovered at Tell-el-Maskhutah (Hoffmeister 59), so I am not averse to this theory. Nevertheless, there are problems with Naville’s identification.

Naville pointed out that Pi-Tum was usually described in Egyptian texts as being “at the Eastern door”, which seems to imply that there was a border crossing between Egypt and Sinai at Pithom. If there was such a place at the time of the Exodus, then it would make sense for the fleeing Israelites to set off in that direction. On the other hand, it is quite possible that Naville was simply wrong when he placed Pithom in the Wadi Tumilat. If there was a border crossing here, and if the surrounding district was used by the Bedouin to graze their herds and pitch their tents, then there must have been a corridor of dry land here between Egypt and Sinai. The Bedouin could not have entered Egypt here with their herds if there was a body of water—a lake, a canal, or even a gulf of the Red Sea—blocking their path. They would, instead, have travelled further north towards the Way of Horus, where they could have simply walked dryshod into the Delta.

And this is the next problem that we must resolve if we are to have any hope of tracing the itinerary of the fleeing Israelites: What was the extent of the Red Sea coast of ancient Egypt at the time of the Exodus? The answer to this question will have a significant bearing on our quest, and may even shed some light on the problem of Pithom.

To be continued ...

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), _The Jewish Study Bible , Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- Heinrich Karl Brugsch, Geographica, in C R Lepsius (editor), Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, Volume 13, pp 5-13, J C Hinrichs’sche, Leipzig (1875)

- Heinrich Karl Brugsch, The True Story of the Exodus of Israel, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Francis H Underwood, Lee and Shepard Publishers, Boston (1880)

- E A Wallis Budge, An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, Volume 2, John Murray, London (1920)

- Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible ... With a Commentary and Critical Notes, Volume 1, G Lane & P P Sandford, New York (1843)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- Jerome, Epistle to Fabiola, Epistolae: Medieval Women’s Letters, Translated and Edited by Joan Ferrante, Columbia University (2014)

- Flavius Josephus, William Whiston (translator), Syvert Havercamp (editor), The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus, The Jewish Historian, A C Armstrong & Son, London (1737)

- Johann Heinrich Kurtz, History of the Old Covenant, Volume 2, Translated by James Martin, Lindsay & Blakiston, Philadelphia (1859)

- Édouard Naville, The Store-City of Pithom and the Route of the Exodus, Fourth Edition, Messrs Trübner & Co, London (1903)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia, Volume 5, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Paul Pierret, Vocabulaire Hiéroglyphique, F Vieweg, Paris (1875)

- Jeffrey Spencer, The Exploration of Tell Belim, 1999-2002, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Volume 88, pp 37-51, Sage Publications Ltd, London (2002)

- James Strong, The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

- John A Wilson, Buto and Hierakonpolis in the Geography of Egypt, _Journal of Near Eastern Studies _, Volume 14, Number 4 (October 1955), pp 209-236, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1955)

Image Credits

- Heinrich Karl Brugsch: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Ruins at Tell-el-Maskhutah: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Henri Édouard Naville: © Fondation Naville, Genève, Fair Use

wow great..

we need more historical information like this, since this make as aware about our past and make our future better.

Thanks for the author :)

This is much historical information sir thanks