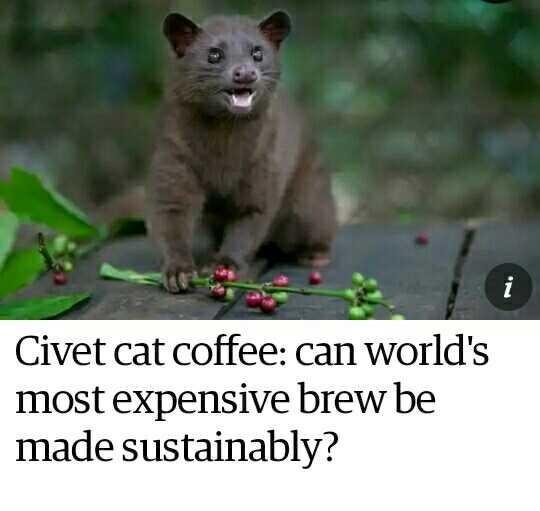

Civet cat,,luwak

lantation and selects only the finest, ripest coffee cherries to eat. Only it can’t digest the stone (the coffee bean) and craps them out, its anal glands imparting an elusive musky smoothness to the resultant roasted coffee.

And when, as coffee director of Taylors of Harrogate, I first brought a small amount of kopi luwak to the west in 1991, that repulsive charm worked wonders with the press and public, and my kilo of luwak beans caused a stir wherever I took it.

But the charm has now evaporated, and the only thing left is the repulsive. Kopi luwak has become hugely popular worldwide, and as a result wild luwaks (palm civets) are being poached and caged in terrible conditions all over South East Asia, and force fed coffee cherries to produce commercially viable quantities of the precious coffee beans in their poo.

But even as these cruel battery farms, especially in Indonesia, were pouring out tonnes of it a year, the coffee trade was still pedalling the myth that kopi luwak was incredibly rare, derived from coffee chosen by discerning wild luwaks.

That myth was well and truly exploded by the Facebook campaign (Kopi Luwak: Cut the Crap!) I launched a year ago. Shocked at the thought that my original innocent purchase could have spawned such a monster, my original aim was to persuade consumers, retailers, importers, exporters and producers of kopi luwak to end their involvement in this cruel, fraudulent trade.

Kopi luwak

Kopi luwak coffee. The brown beans are before roasting, whiter beans afterwards. Photograph: Alamy

I’ve since teamed up with partners such as World Animal Protection (WAP) and change.org and the effects have been dramatic. Under pressure from us – and from their own customers – leading UK retailers such as Harvey Nichols and Selfridges have ceased to stock kopi luwak, and retailers in Holland, Scandinavia and Canada have committed to dropping it too. Coffee certifiers such as Rainforest Alliance and UTZ are banning its production from their estates.

But late last year there was an unexpected development with Harrods. They found a new supplier, Rarefied, which they claimed was the real deal, a producer of genuine wild kopi luwak. Not only that, they invited me to meet its founder, former Goldman Sachs banker Matt Ross, and check him out.

Deeply sceptical at first, I was ultimately impressed. Rarefied’s foundational principle is that their coffee is guaranteed wild, and it has put in place solid, demonstrable systems to ensure it is the case. Matt took me through the process, step by documented step. Not only that, but I could suddenly see that there were additional benefits in terms of habitat and biodiversity conservation, and smallholder education and income. Kopi luwak, far from being the monster I thought I’d created, could actually provide a sustainable livelihood. Provided, of course, that it’s genuinely wild.

Rarefied’s kopi luwak is called Sijahtra and comes from the Gayo Mountains district of northern Sumatra. Matt and his partners have about 40 coffee farmers on the company’s books, typically from the more remote areas, each with a couple of hectares and close to or abutting the rainforest – the luwaks favoured habitat, where they nest in trees. They are natural omnivores, but when the weather is cold and wet (and at 1,500 meters above sea level, even on the equator, that is quite often), luwaks seem to welcome the caffeine boost that eating ripe coffee cherries gives them.

The farmers are shown how to collect the resultant scats containing the coffee beans while they are still fresh and bring them to a central processing factory where they are assessed for quality. At this stage it’s possible to tell the difference between wild and caged kopi luwak by the appearance of the faeces, which tells the story of what the animals have been eating in addition to coffee cherry.

Civet coffee beans

Scats containing coffee beans. Photograph: Joel T Sadler 2014

The farmers are well-trained and strictly monitored, and if any of them attempts to pass off caged kopi luwak as wild, they are instantly banned. If the kopi luwak they collect passes muster, they are paid very well for it, some 10 times what the caged equivalent would fetch (the aim, says Ross, is to return 5% of the sale price to the farmer – $100 a kg). But the amount they are allowed to bring in monthly is strictly limited – a quota system that further helps to guarantee authenticity.

All this care and attention to detail comes with a hefty price tag – Harrods are currently selling Sijahtra at £200 per 100 grams – but there are plenty of customers there and around the world willing to pay for what is seen as the ultimate luxury coffee.Hearing about Sijahtra kopi luwak has had a significant effect on my Cut the Crap campaign aims. I’ve realised that potentially there is a sustainable business model in genuine wild kopi luwak. While still calling for the end of the cruel practice of using captive luwaks for coffee production, I’ve now joined with Harrods and WAP to lobby for the creation of an independent certification scheme for genuine, wild kopi luwak based on similar monitoring systems.

We’ve even persuaded the Indonesian government to support the concept of a certification scheme for what they call their “national treasure”. And more recently the Speciality Coffee Association of Europe, one of the most influential trade organisations in the coffee world, has acknowledged that there is a problem with caged kopi luwak, and have come out in support of our independent certification initiative too. The aim would not necessarily be to emulate Sijahtra’s extremely high quality control levels (and price tag), but to guarantee that the coffee was wild, and thus by its nature, sustainable.

Wild kopi luwak could provide smallholders with a premium product that also helps conserve the animal’s natural forest habitat. Maybe not so repulsive after all...

Tony Wild is the author of “Coffee: A Dark History”