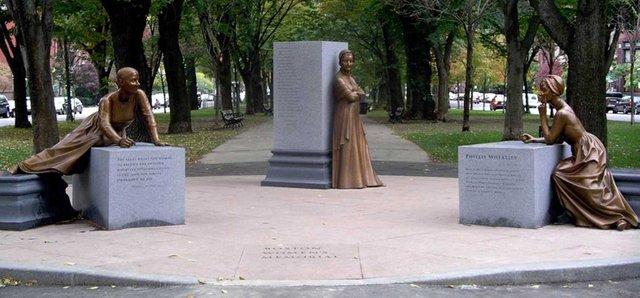

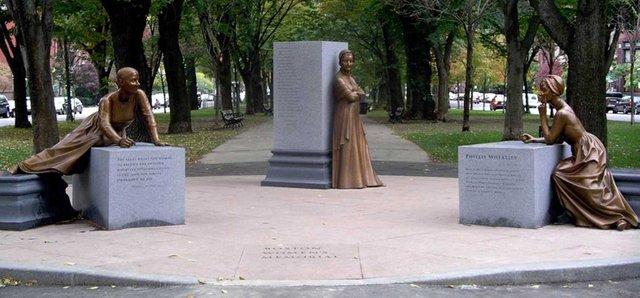

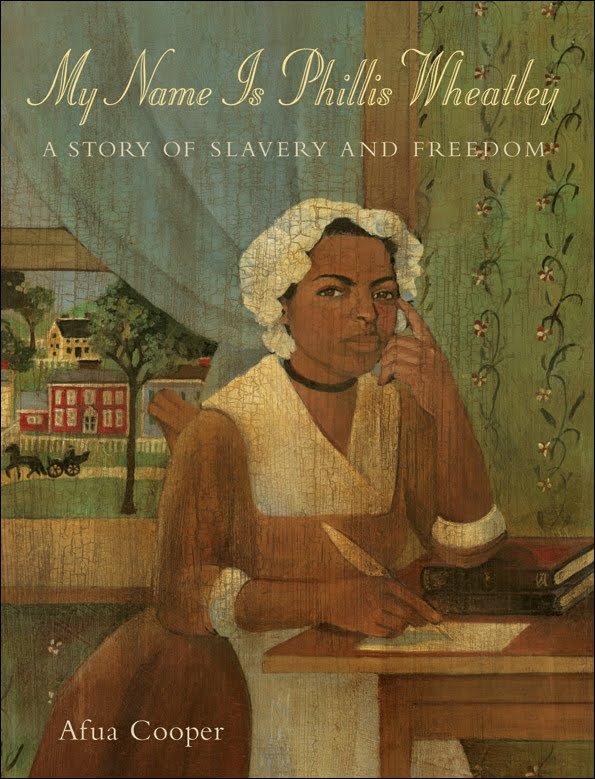

Phillis Wheatley and the Birth of African American Consciousness

Greetings, Steemians, continuing with the posts on first African American poet, Phillis Wheatley, here is the second part of the essay. Hope you enjoy it. You can find the previous post here: https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/subverting-the-scriptural-tradition

Your comments, as always, are more than welcome!

Source

Source

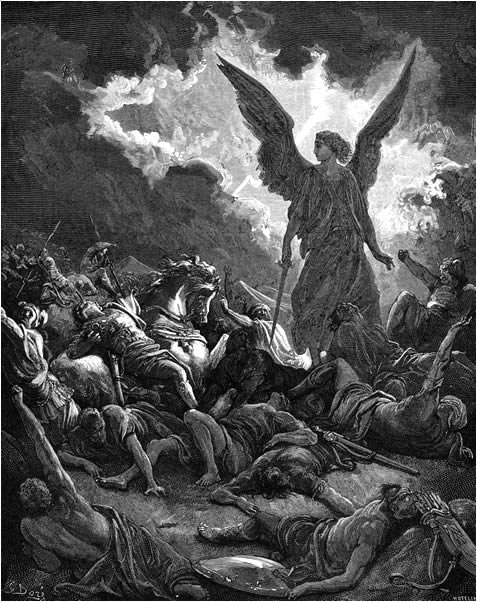

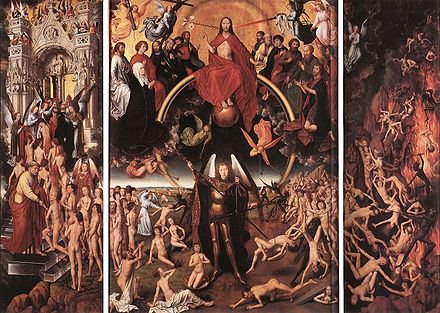

The Epyllia

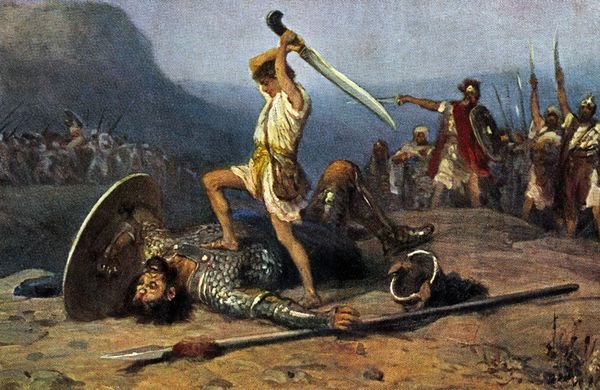

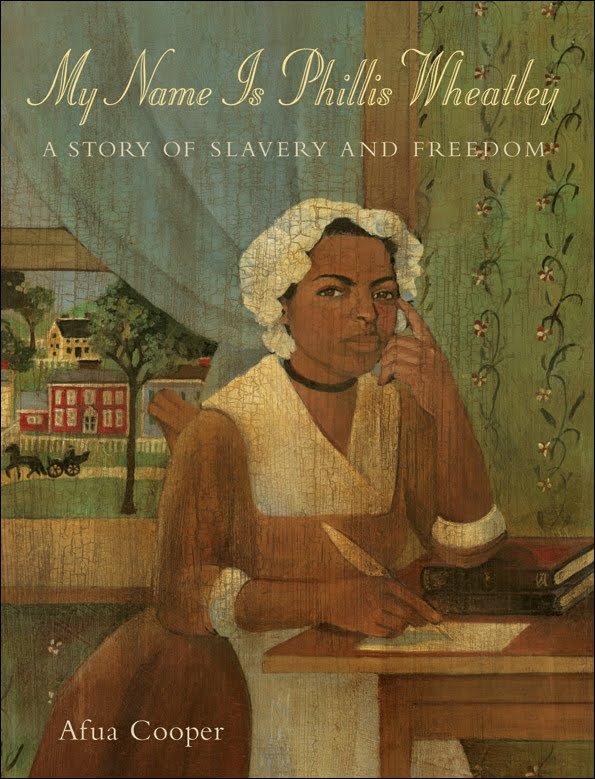

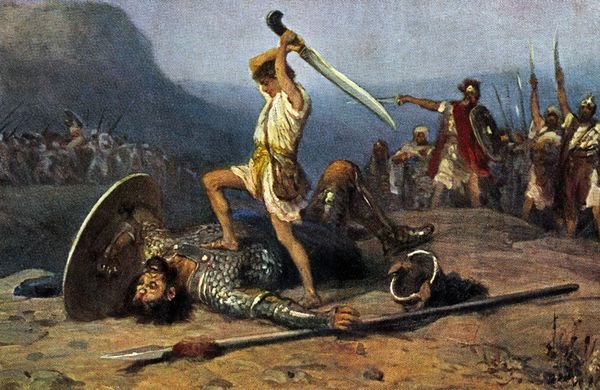

I have chosen On Isaiah and Goliath of Gath to illustrate two different, yet equally powerful ways Wheatley paraphrases biblical texts; in the first one, I argue, Phillis adopts a public voice, the second one is a more private one, given the likeness between the hero of the story and the poet herself. The main feature in both poems, which separates Wheatley from other poets of her time, is the epic style marked, among other attributes, by the invocation to the muses. Mather Byles’ “Goliath’s Defeat: In the Manner of Lucan,” as Shields says, might have suggested Wheatley the story of David and Goliath (Wheatley’s use of Classicisms 105, American Aeneas 220); however, Byles’ poem lacks the imaginative epic proportion of Wheatley’s epyllion. Byles did not utilize invocations to the muses in his rather “bombastic” version either.

Source

Source

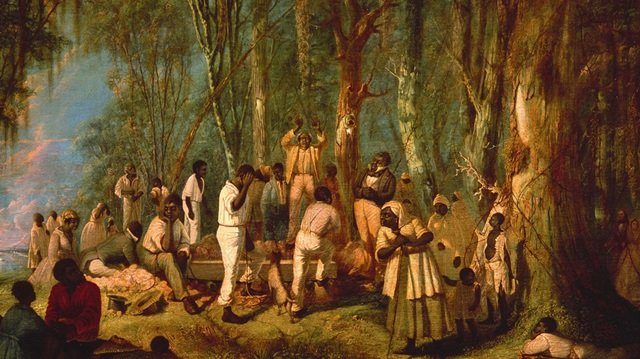

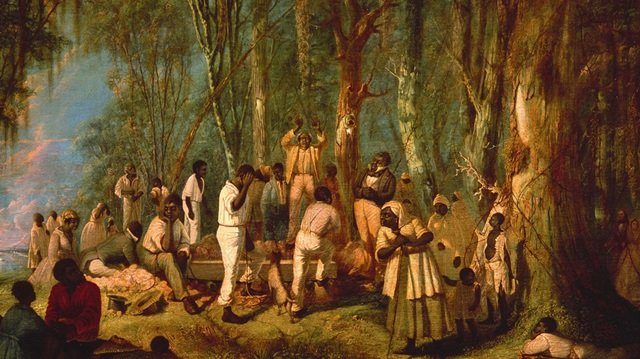

What I find most fascinating about Wheatley’s biblical paraphrases is not what she included in the poems but what she left out. I think it is safe to say that her selections were intentional and well thought out; she knew she could not say more than what was allowed, but she also knew that her readers knew the Bible (although most of them misinterpreted it) and she knew that when they put her poem down they would be thinking about the allusions or implications it made. As Sondra O’Neale puts it, “Wheatley solved two problems: how to write poetry and prose while being a slave, and how to find an authentic language that could offer consolation to fellow slaves while prodding the consciences of their enslavers” (158).

Source

Source

Wheatley realized that the biblical language was the most immediate vehicle to get to both white and black minds and touch them with “dread image[s] of the Pow’r of war” (Wheatley 60: 6). By using key stories of the bible and turning them into part of her subversive poetic repertoire, Wheatley demonstrated not only that she mastered the genre, but also that she understood the complexity of the slave problem; she knew the internal contradictions of the “peculiar institution” and assumed a prophetic role in voicing the scriptural instances in which blacks could see their cause defended and won.

Source

Source

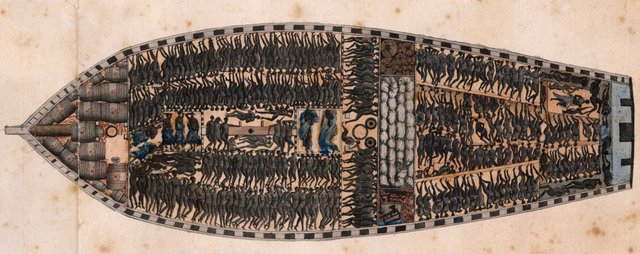

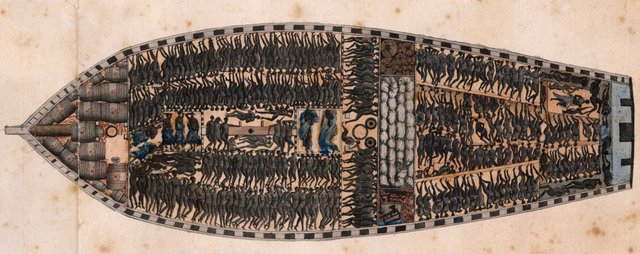

In Isaiah, a 30-line poem, Wheatley vents what I argue was her unconscious/restrained state of anger and frustration, her inner desire for revenge. The passage must have evoked in Wheatley’s mind a bitter image of the middle passage. Her anger, therefore, comes from the image of her fellow black people (including probably some relatives) being “compressed” on a ship’s lower deck, just like grapes on a “groaning press.” A vision of a vengeful redeemer was the only possible reparation Wheatley might have considered at some point.

“Compres’d in wrath the swelling wine-press groan’d,

It bled, and pour’d the gushing purple round” (60:7-8).

Source

Source

Wheatley based the poem on Chapter 63 of Isaiah, verses 1 through 8. That section follows chapter 62, which contains some of the promises God made to his chosen people (especially those regarding the rewards for toiling the land—62: 8, 9, 12) and precedes chapter 64, which is a complaint about God’s indifference to the suffering of His people and a call for Him to “come down” and avenge them (64: 1, 2). More interestingly, Wheatley must have read verse 16 in chapter 63 as her own people’s plead, “But you are our Father, /though Abraham does not know us/or Israel acknowledge us; / You, O LORD, are our Father,/ our Redeemer from of all is your name.”

Source

Source

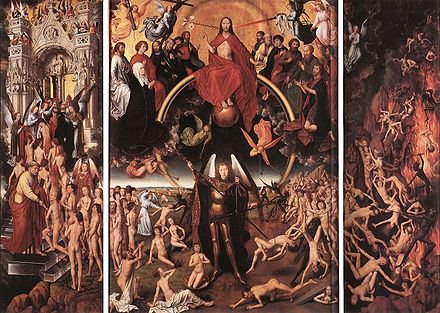

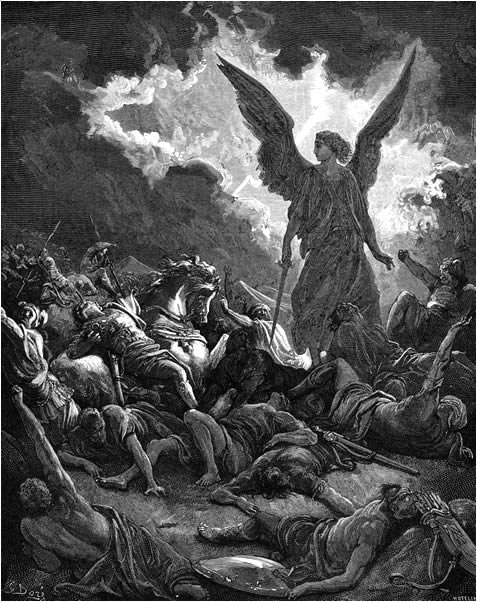

There are clear connections between the stories narrated in Isaiah 63 and I Samuel 17, the former being the anticipation of the latter. Keeping in mind that nothing is accidental in Wheatley’s ingenious oeuvre, Shields’ theory of “intertextual epic” makes even more sense. As William Scheick asserts, “Isaiah’s vision foretells the coming of a David-like figure who will release the Israelites from their captivity” (126). We know that already in her juvenilia Wheatley had made a distinction between God and “Saviour.” She was also more prone to link “Saviour” to “Redeemer,” a term more closely associated at the time with the racial and economic intricacies of indented servitude, an option “not available to most Africans (O’Neale 149). Now, if we consider that Wheatley knew that the bible did not condemn the black race to slavery (therefore spiritual salvation was guaranteed to all), and if we equate “Saviour” with redeemer in Wheatley’s language, then when we read in Isaiah that the “Almighty Saviour”… “For man’s releafe sustain’d the pond’rous load,” we know that she means relief from slavery, more than from damnation. Similarly, we can assume that “the wrath of an immortal God” is addressed to the oppressors not to the “sinless” Africans like herself, a “blameless race” as she puts it in On the Death of General Wooster.

Source

Source

There is a call to individual action that can be read between the lines of Isaiah. “Mine was the act," th' Almighty Saviour said, / And shook the dazzling glories of his head, /"When all forsook I trod the press alone, /"And conquer'd by omnipotence my own.” In other words, Wheatley identifies herself with the lonely warrior who despite frustration can “conquer” her own “glories.” The how is not revealed in the poem, but in the bible: “my own wrath sustained me” (63:5).

Source

Source

This powerful line should be considered as a sub-text in Wheatley’s biblical paraphrases, a shared aspect with Goliath, both portraying very dramatic (in fact epic) biblical moments; moments that evoke not only power, but also a profound state of anger and desire of revenge. All those words: power, wrath, and revenge are consistently present in Wheatley’s poetry, which suggests her obvious indignation with her enslaving state and that of her fellow Africans, contrary to what some scholars, such as Blyden Jackson, have suggested: that Wheatley did not include in her poetry a “note of open protest against racism” (45).

The Heroine

Source

Source

In Goliath of Gath, the fact that Wheatley, unlike Byles, departs from the literal rendition of the biblical story, speaks volumes of how fervent she was to the godly tenants of the white man’s religion. It was more important for the black poet to render a story that was artistically creative, personally poignant, and politically piercing. Whether she was effective or not is a different story. Unlike future black abolitionists like Frederick Douglas (1817-1895), she was first an artist committed to her poetic craft (a vehicle less effective than sermons, lectures, or editorials), and then a woman, black on top of that, restricted in many ways from the historical advantages granted to subsequent black voices.

Thanks for the visit. I will be posting the last part of this analysis shortly.

Works Cited or Consulted

• Jackson, Blyden. A History of Afro-American Literature. V I. The Long Beginning, 1746-1895. Louisiana State U.P.: BatonRouge, 1989.

• O’Neale, Sondra. “A Slave Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol.” EAL 21.2 (1986): 144-65.

• Scheick, William J. “Subjection and Prophesy” College Literature 22.3 (1995): 122-29.

• Shields, John C. The American Aeneas. University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, 2001

• ---. “Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism.” American Literature 52 (1980): 97-111.

• ---. “Phillis Wheatley and Mather Byles: A Study in Literary Relationship.” CLA 23.4 (1980): 377-90.

• Wheatley, Phillis. The Collected Works. Ed. John Shields. Oxford UP: Oxford, 1988.

Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source

Mi voto. Espero la traducción. Un abrazo.

Thanks for the support. Translation in the oven :)

Cocinando la traducción. Un abrazo.

Igual que @solperez, te espero en la bajadita. Saludos, hermano.

Jajaja. Me hiciste recordar un manganzón que me hacía bullying en la escuela. Sonó como a..."Te espero a la salida". No te lo agradezco.

She did know how to use the Bible to raise her fellow people's awareness about their slavery condition and injustice in general .