From “Leave Everything to God” to “Leave God out of (almost) Everything” (Part I).

Source

Source

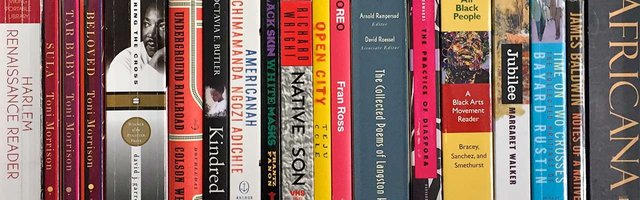

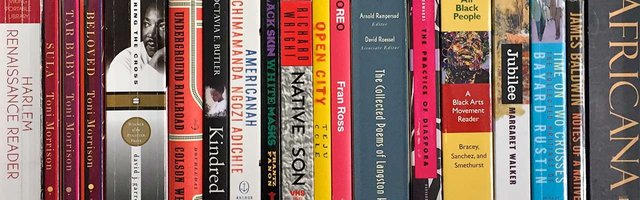

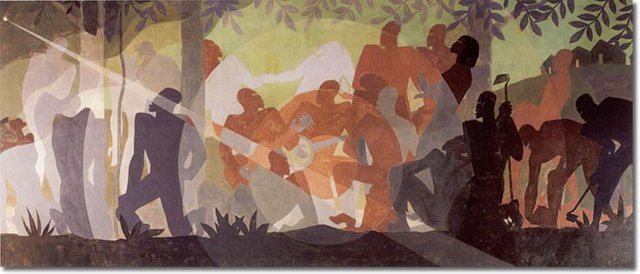

Greetings, Steemians. Continuing with my posts on African American literature, I would like to share with you some thoughts about some of the writers who followed Phillis Wheatley’s steps to consolidate the first wave of literature written by blacks, most of them born into slavery.

Religion is going to play a key role in the process of humanization and visualization of African Americans’ intellectual merits. From the tedious piousness of Jupiter Hammon, to the back-to-Africa theology of John Marrant, all the way to the separate-but-equal obliging position of Booker T. Washington, African Americans will appropriate the white man’s religion to claim their rights to humanity and citizenship. In some cases, perpetuating their condition, in others subverting the order and causing revolutionary events.

Source

Source

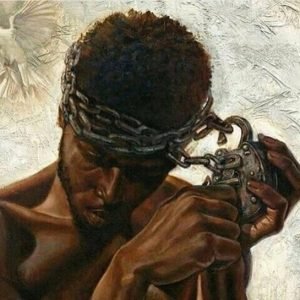

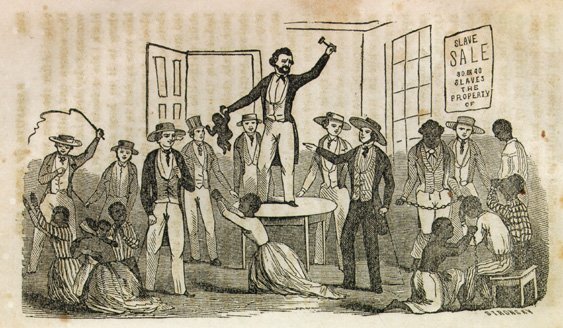

From 1773 to the beginning the 20th century, African Americans will partake of the main literary genres of their times, such as poetry, essays or lectures, sermons, and sentimental novels. In the process, they will create new genres, such as the slave narratives, which will contribute, more than any other, to denouncing the atrocities of slavery and furthering the cause of freedom, equality and the pursuit of happiness. No other genre will be more poignant in revealing white America’s contradictions and immoralities.

Theological and Ontological Changes in African American Poetry:

Although writing a decade before Wheatley, Jupiter Hammon’s poetry (1711–1806?) did not have the same impact in the development of the artistic form or the uplifting of the race. In my opinion, they were too pious and concerned with conversion and faith in Jesus’s redeeming role. For Hammon, “God alone can give us peace;/It’s not the pow’r of man.” Even though it was implicit in his poetry that the cultivation of virtue pertained to both blacks and whites, there is little to be drawn from his poems as direct indictment for whites’ immorality in the perpetuation of slavery. Hammon`s poetry is not included in Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s Anthology of African American Literature. His poems and sermons served more as white propaganda and indoctrination, leaving art, imagination and racial consciousness outside.

Hammon’s merit resides in being the first African American to be published in the United States. His An Evening Thought… was published in 1761.

Dear Jesus unto Thee we cry,

And make our Lamentation:

O let our Prayers ascend on high;

We felt thy Salvation.

Lord turn our dark benighted Souls;

Give us a true Motion,

And let the Hearts of all the World,

Make Christ their Salvation.

Source

Source

Some years after Wheatley’s collection of poems was published, Hammon would publish an appeal to Phillis Wheatley where he reminds her, echoing her own poetry, that it was God’s mercy that brought her from her pagan land and that she must avoid deviating into sinful ways (alluding to Wheatley’s ambiguous feelings towards Christianity, as I explained in previous posts):

Come you, Phillis, now aspire,

And seek the living God,

So step by step thou mayst go higher,

Till perfect in the word.

[…]

Thou, Phillis, when thou hunger hast,

Or pantest for thy God;

Jesus Christ is thy relief,

Thou hast the holy word.

Source

Source

Hammon’s submissive position is more evident in his sermons. His famous “Address to Negroes of the State of New York” (1786) speaks for itself:

“I published several pieces [in Hartford, Connecticut] which were well received, not only by those of my own colour, but by a number of the white people, who thought they might do good among their servants.”

I think you will be more likely to listen to what is said, when you know it comes from a negro, one your own nation and colour, and therefore can have no interest in deceiving you, or in saying any thing to you, but what he really thinks is your interest and duty to comply with.

Hammon offered his audience of fellow slaves three particulars, which should help them bear their enslavement with fortitude and pride: obedience to their masters, honesty, and faithfulness.

Source

Source

Even though Hammon acknowledges liberty’s worth and greatness, he considers that it may be a good thing for the young (“if we can get it honestly, and by our good conduct”), but old slaves would not know what to do with freedom, having gotten used to taking care of masters, they would not know how to take care of themselves. Freedom from slavery should not be their priority, Hammon argued. Spiritual freedom, conversion, was more important. Similarly, he encourages them to learn to read, but the Bible was for Hammon the only book worth reading. “Reading other books would do you no good. But the Bible is the word of God, and tells you what you must do to please God.” Despite the pains and tribulations of slavery, Hammon found solace in the idea of afterlife happiness and eternal reign with Christ (and their masters, if they were Christians, like most were!).

Hammon does say something worth of praise when he addresses free blacks at the end of his sermon. He invites them to live a decent life, based on godliness, hard work, and honesty. Doing otherwise would have done more harm to the cause of those still in bondage than anything else, for it would perpetuate the stereotypical excuses whites had used to deny blacks their freedom: that they were lazy and would not be able to take care of themselves, that they would go wicked ways and succumb to vices. This warning still causes dispute among African Americans when it comes to their sense of duty and responsibility in providing role models for poor blacks to imitate and aspire to.

Source

Source

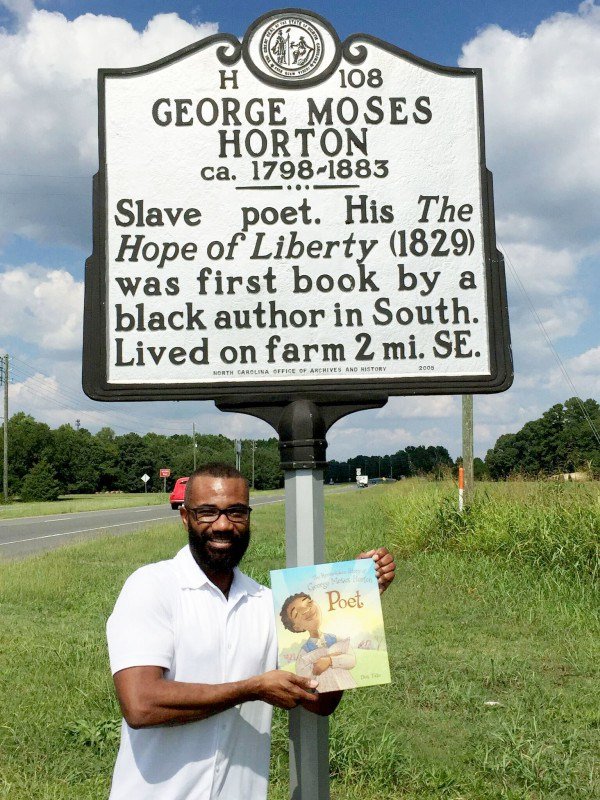

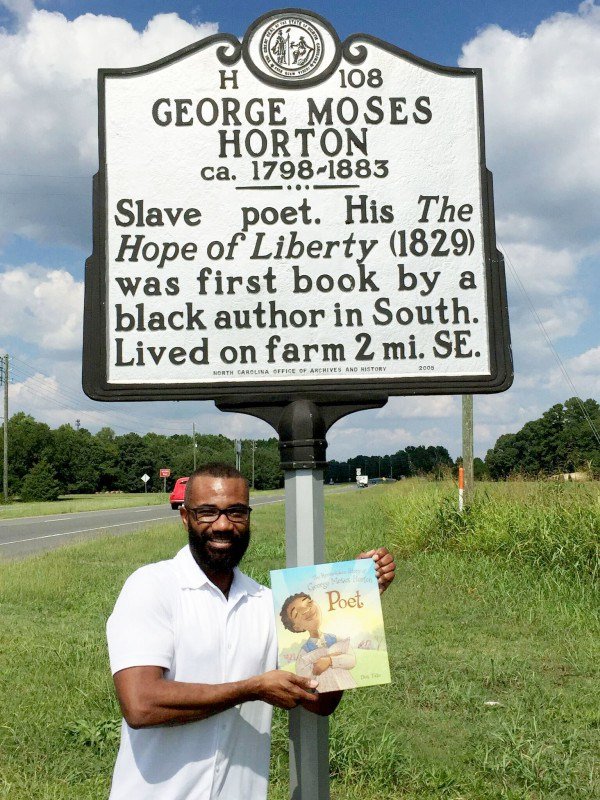

When we compare Hammon’s submissive simplicity and tone with Wheatley’s poetic voice, we can see why she comes on top of early black writers (male or female). We will have to wait until George Moses Horton’s (1797?-1883?) poetry comes up to see Wheatley’s ideas taken a step further.

Source

Source

Writing sonnets and ballads, Horton departed from the contemporary European poetic style and voice by making the contradiction of his poetic nature and enslaved condition the center of his work. He was born a slave in North Carolina and got his freedom by the end of the Civil War (1865), he was almost 70 years old. He taught himself to read and at early age was fully aware of his artistic sensibility. He even began to make business with his poetry by composing “made-to-order love poems for students willing to pay twenty-five to seventy-five cents per lyric, depending on the length and complexity” (Gates 190). In exchange he also got books by classic English authors, which in turn contributed to the development if his style. He got his first poems published by 1828. The next year his collection of poems, The Hope of Liberty became the only poetry book by an African American after Wheatley’s.

Horton’s poetry spans from antebellum to postbellum America and reflects the vision African Americans had in regards to the damage slavery would do to the Union if not abolished. It also spans from the personal pain narrated in The Lover’s Farewell (1829) to the collective pain of Division of an Estate (1845), down to the retrospective insight of past and future, conditioned to the preservation of personal and political liberties in George Moses Horton, Myself (1865).

Source

Source

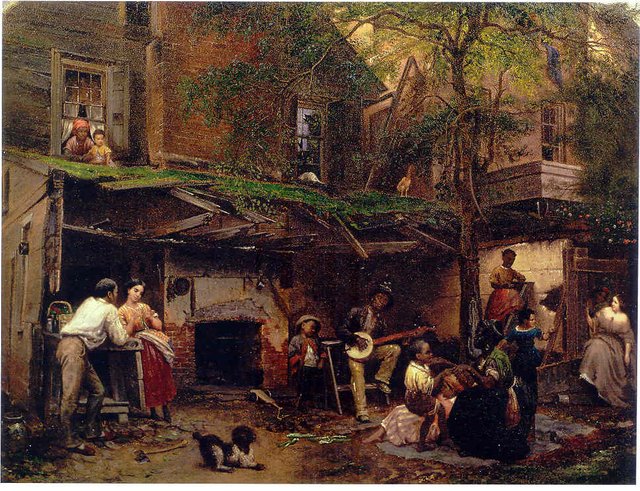

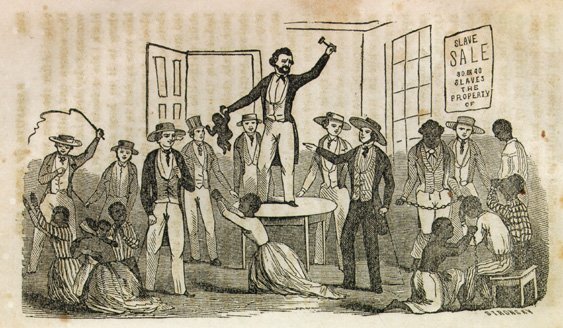

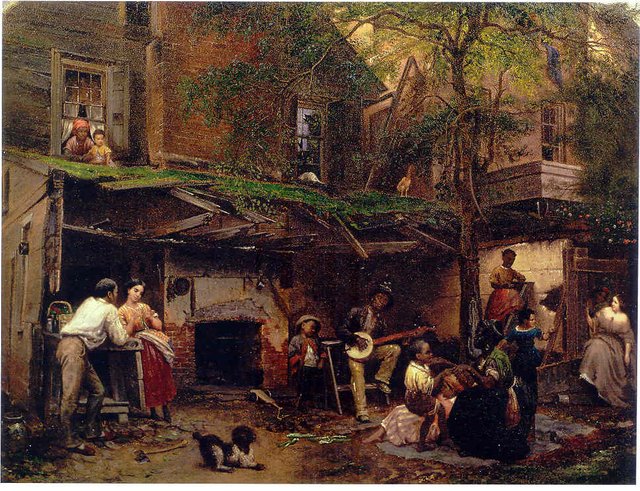

One of the most traumatic experiences in the life of slaves had to do, not so much with hard work and physical punishment, which, as many voices documented, was tolerable in the end. What was unbearable was the loss of loved ones; the abrupt separation; the impossibility of free amorous love; the inextricable tragedy of being owned and disposed of at a master’s (or even a mistress’s) caprice. Horton encapsulates in The Lover’s Farewell the drama of revealing a love interest, losing it, and/or running away because of it.

And wilt thou, love, my soul display,

And all my secret thoughts betray?

I strove but could not hold thee fast,

My heart flies off with thee at last.

This tragedy also applied to separation from children, a motif that will become ubiquitous to slave narratives, either by black or white authors.

Source

Source

I leave my parents here behind,

And all my friends--to love resigned--

'Tis grief to go, but death to stay:

Farewell--I'm gone with love away!

As we can see, Horton adds the emotional element and the overt denunciation of a reality previous writers dealt with euphemistically. The idea that slavery was as good as death was a revolutionary notion; one that many modern writers, such as Toni Morrison, will revisit and represent for modern readers more poignantly.

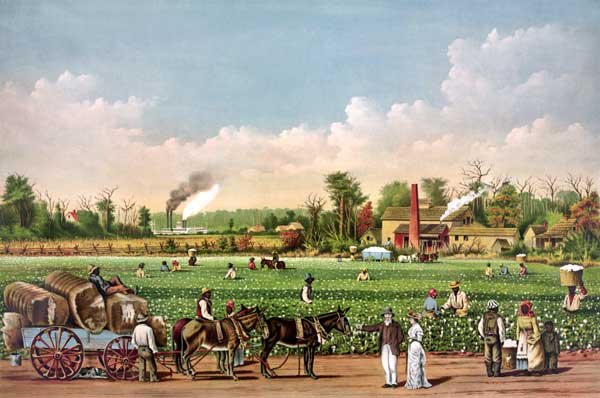

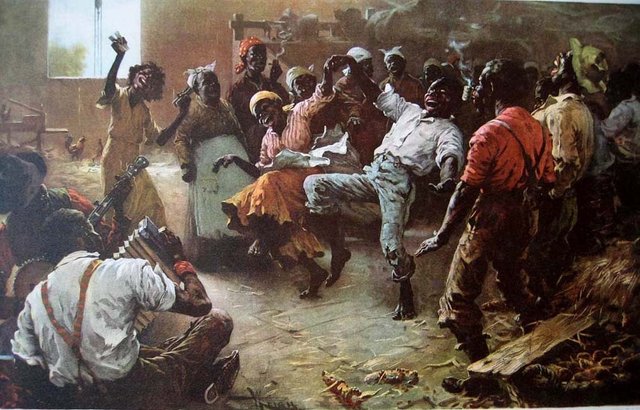

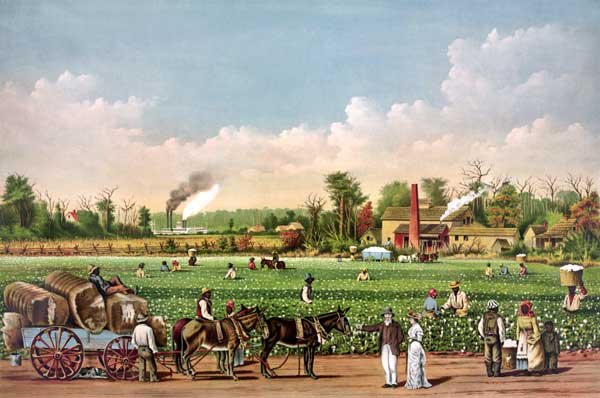

In Division of an Estate (1845), Horton plays with the ambivalent feelings of slave faithfulness and dependence of white masters. He mocks the chaos produced by the death of plantation owner or the change of hands of property, slaves being just one of them.

[…]The flocks and herds,

In sad confusion, now run to and fro,

And seem to ask, distressed, the reason why

That they are thus prostrated.

The poem also hints at the possibility of revolution or emancipation, in which case, Horton—just like the writers around the time of the War of American Independence—is fully aware of the internal divisions among slaves and the fear of emancipation’s imminent failure.

The day of separation is at hand;

Imagination lifts her gloomy curtains,

Like ev'ning's mantle at the flight of day,

Thro' which the trembling pinnacle we spy,

On which we soon must stand with hopeful smiles,

Or apprehending frowns; to tumble on

The right or left forever.

Source

Source

In George Moses Horton, Myself (1865) Horton recalls times past and laments the limitations that slavery imposed on his restless talent.

I feel myself in need

Of the inspiring strains of ancient lore,

My heart to lift, my empty mind to feed,

And all the world explore.

I know that I am old

And never can recover what is past,

But for the future may some light unfold

And soar from ages blast.

He issues what can be considered a declaration of intellectual independence, which should be embraced by every freedom lover.

I feel resolved to try,

My wish to prove, my calling to pursue,

Or mount up from the earth into the sky,

To show what Heaven can do.

Thus, heaven becomes a more human scenario, more accessible to man’s intellect, less confined to spiritual conversion and devotion (with all the limitations implied in that). The restless black intellectuals and artists must, then, spread their wings and sing their songs not just locally, but “from world to world.”

Finally, with Frances Harper (1825-1911) we get to a level of militancy that will serve as a foundation for more radical black thinkers, despite the coexistence of more moderate minds. Harper is probably the most versatile and prolific African American writer of the 19th century. She published four novels, several volumes of poetry, short stories, essays and letters. Besides that, Harper was an educator and active member of suffragist and temperance movements, and, at some point in 1853, Harper quit teaching to dedicate herself to the antislavery movement (Gates 409).

Source

Source

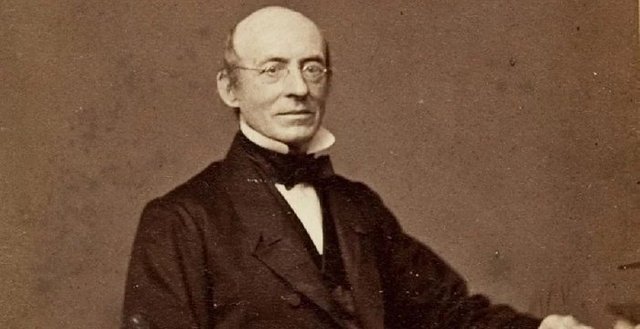

She was acclaimed among black and white abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglas and William Lloyd Garrison and committed herself to intensive lecturing schedules across the country. Much had obviously changed from Phillis Wheatley’s days. On the eve of the Civil War there was no point in African American writers censoring themselves and, despite the persecution and risks to their lives, writers like Harper invested all their talent and energy in a cause that, far from what Hammon argued less than a century before, needed people’s active participation more than blind belief in God’s providence.

Source

Source

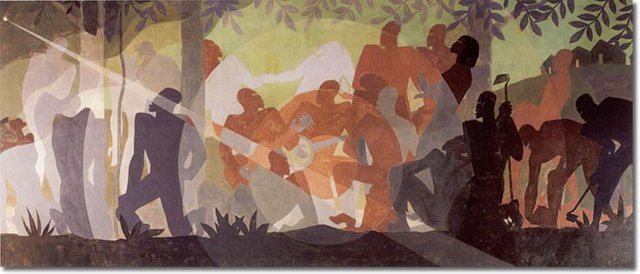

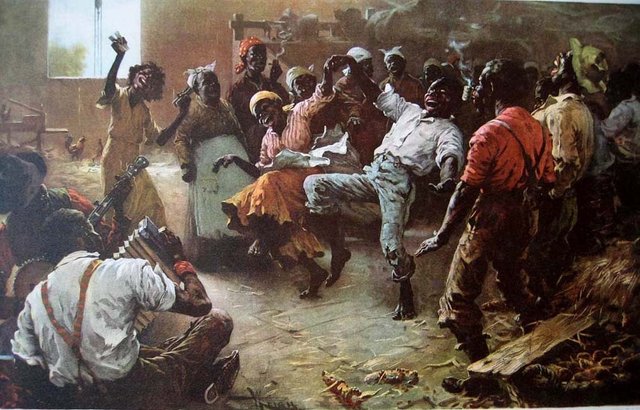

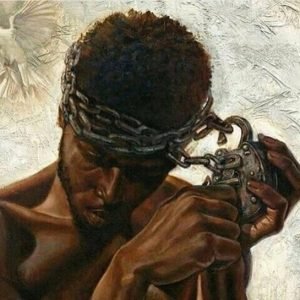

From her antebellum poetry, we can see Harper’s feisty abolitionist and feminist views. We can also see a change in the theology that drives this generation of African American writers. God is no longer terrible and accepting of blacks’ condition. God is not vindictive, but friendly; more importantly, He is just! God, if present at all, is with the blacks and their cause. As it was argued earlier by writers like Equiano (which I will elaborate on in the next posts), blacks start seeing themselves as chosen people. They start seeing themselves in the bible, not like the slaves Hammon advised to be, submissive, hard-working, and faithful, but like the Israelites: slaves who were about to be freed and had the right to claim their freedom by all means necessary. Whites start looking like the Egyptians (and we know what happened to Pharaoh and his people).

Source

Source

In Ethiopia (1853?), we read blacks plead reaching “the burning throne of God”:

The tyrant's yoke from off her neck,

His fetters from her soul,

The mighty hand of God shall break

And spurn the base control.

We see a humbled God that “bends” unto blacks’ “wo” and compensates for all the wrongs. This reversal of the position of the faithful in regards to God is a daring reinterpretation of the Bible. Those who have been wronged by men, and even by God himself (he tends to forget about His people in rather careless ways), do not have to kneel and bow and accept punishment and submission. Instead, they make demands and those demands, just as they are, shall be met.

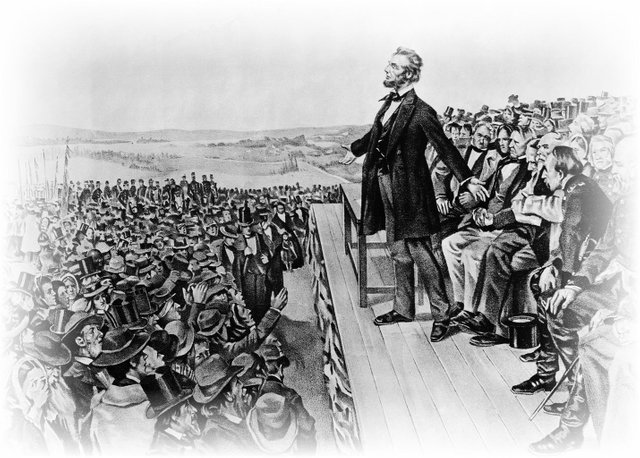

You can imagine the effect a literature like this had in the minds of black readers. The Civil War would be seen, to a certain extent, as the punishment for white stubbornness and impiousness.

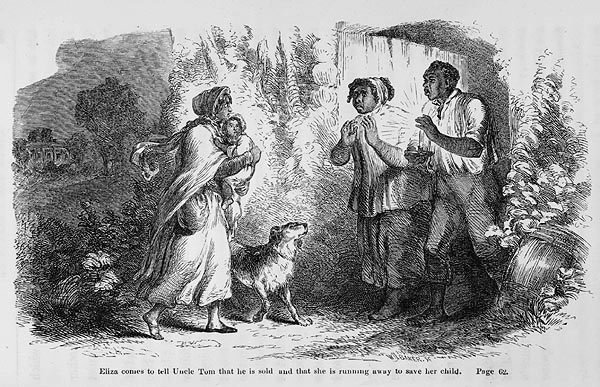

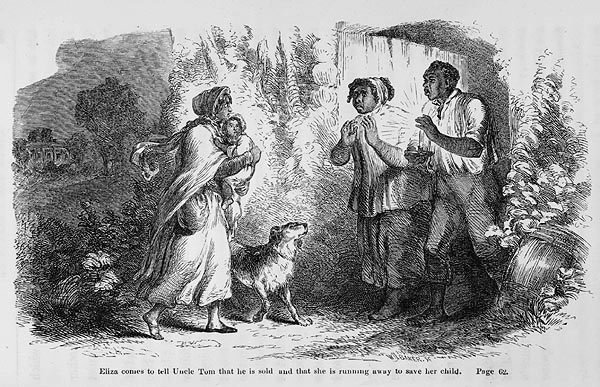

In Eliza Harris (1853), Harper uses the story of an event occurred in Cincinatti, Ohio, which was also used by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her novel, Uncle Tom´s Cabin, to dramatize the escape of a mother and her child who, with God’s help, but thanks to her determination and courage, make it to freedom. They run away from a land where it is a crime to be black; “Where bondage and torture, where scourges and chains/Have plac'd on our banner indelible stains.”

Source

Source

In The Slave Mother (1854), Harper makes the reader hear the shrieks of a desperate woman whose son is being sold by “cruel hands”. She makes readers see the clasped hands, “The bowed and feeble head—/The shuddering of that fragile form,” and the grim and dreadful look of the mother. Unlike Wheatley’s poem, there is not sense of hope here; no sense of thankfulness for a future conversion that may bring peace and comfort. There is only heartbreaking pain:

They tear him from her circling arms,

Her last and fond embrace.

Oh! never more may her sad eyes

Gaze on his mournful face.

No marvel, then, these bitter shrieks

Disturb the listening air;

She is a mother, and her heart

Is breaking in despair.

Source

Source

The contributions of these writers and many others, along with white abolitionists, will exacerbate the political tensions about the “peculiar institutions” the Founding Fathers found so difficult to eliminate. In the years that followed the Civil War, the lives of the now emancipated blacks will not get any easier, but their now emancipated minds will only get sharper, more creative, impassioned, and irreverent.

In the next part of this post, I will examine the essays and lectures that contributed their share to the development of African American literature during this period.

Thanks for your visit. Your comments, as always, as more than welcomed!

Works Cited or Consulted

• Gates Jr., Henry Louis and Nellie Y. McKay. Eds. The Norton Anthology African American Literature. Norton. New York, 1997.

• Hammon, Jupiter. Address to the Negros in the State of New York. Carroll and Patterson: New York, 1787. Electronic Text in American Studies. University of Nebraska—Lincoln.

• ---. Poems. Poemhunter.com. 2012.

• Harper, Frances E. W. Selected poems. In The Norton Anthology African American Literature. Norton. New York, 1997. (408-36).

• Horton, George Moses. Selected poems. In The Norton Anthology African American Literature. Norton. New York, 1997.

• Wheatley, Phillis. The Collected Works. Ed. John Shields. Oxford UP: Oxford, 1988.

Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source

Las imágenes son hermosas. Espero la traducción. Muchos éxitos

Thank you, dear. Working on the spanish version.

There are marked differences in the styles of each author. Harper's writings were more rebelliuos. Norton's were more personal and intimate , I guess. Great Job. Ideas were clearly expressed.

Thanks for taking the time to read and comment. Great job those translations you've been working on, by the way.

Excellent job! Thanks to your posts I'm learning a little bit more about culture and literature.

Thanks for stopping by. It makes me very happy to contribute my bit to your cultural awareness.