What I Learned in School and the Battle for Western Civilization, Part 2

This is the second in a series of articles titled What I Learned in School: The Battle for Western Civilization. The first article focused on what I had learned in school about the West; mostly that white people were evil and the United States was the ultimate source of slavery. This went from first grade until my senior year of university. It wasn’t until I stepped into the realm of researching for myself that I discovered most history I learned in school was a flat-out lie. This article will focus on some of the tools I acquired to approach history with, and to make history a practical and riveting subject.

(You can read the first article here: Part 1, What I Learned in School.)

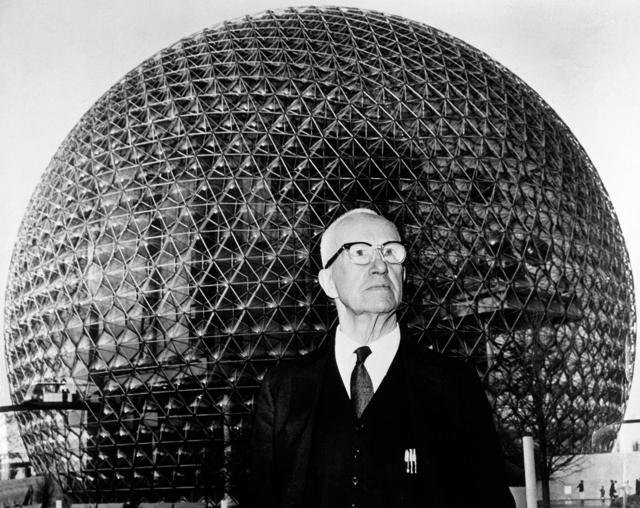

Carroll Quigley, image source.

DEPROGRAMMING HISTORY, AND DEPROGRAMMING MYSELF

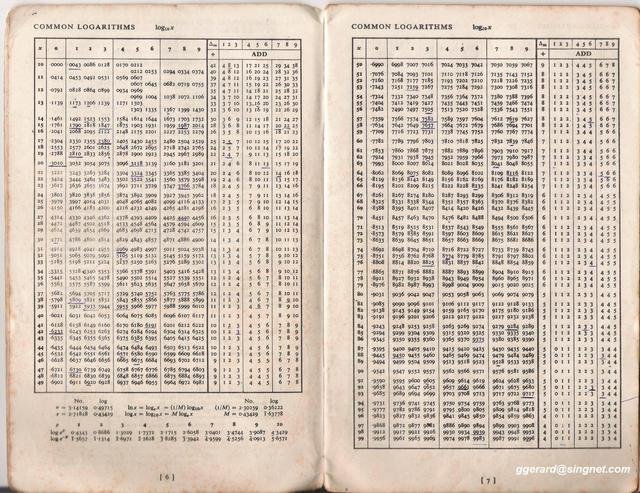

The worst thing I found about history class was there was no way to make any sense of it. Memorizing names and dates for history tests felt like memorizing logarithmic and trigonometry tables for math class; in math class we had calculators to hold our memories for us. Couldn’t we just use encyclopedias (this was before everyone had high speed internet) to look up the exact date that a battle happened or the specific name of a important figure in history? What was all this vague knowledge relevant to? All my history lessons felt like I was reading boring novels where the authors didn’t understand basic literary concepts and drama build up. They all just seemed random.

"Come on class, why can't you guys pay attention? You're going to need to know this later in life." Image source.

I hated history classes so much I managed to escape not having to take a single one during my four years at university. I was a chemistry major, and I couldn’t for the life of me figure out how history was relevant to my studies. In fact, I couldn’t figure out how history was relevant to anything at all compared to a hard science like chemistry. I was learning real, practical science. History was for hobbyists who planned on living in their parent’s basement after graduation.

This attitude was common among students in my chemistry classes. We really looked down our noses at other subjects (probably because we were jealous that they were so easy compared to what we were doing). All that other nonsense was just a waste of time; we were doing real work.

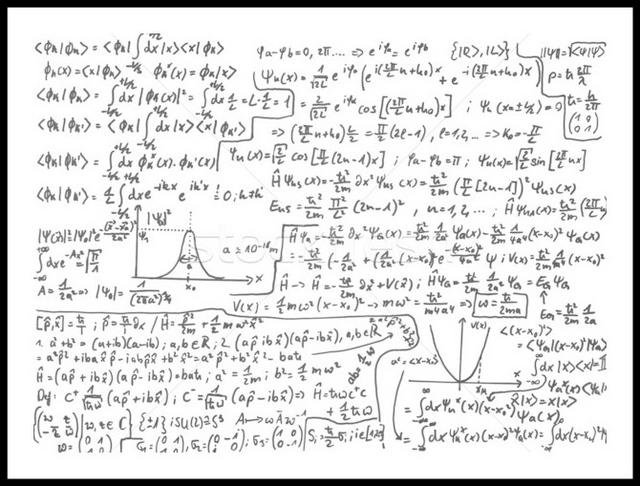

You should be able to tell me if this is proton or carbon-13 NMR. You can't? Phff. Must be an English major. (Image source.)

I had a rude awakening my junior year.

During college, I went home regularly to spend time with friends and train at my Aikido dojo. I had a particular friend who was obsessed with books and podcasts. I would go over to his house and we would go through his library on every conceivable (and inconceivable subject) you can imagine. We would smoke weed, play chess, listen to music, and discuss politics, religion, aliens, the occult, economics, banking, science, agriculture, and anything we could grasp before the THC made it all incomprehensible and I would crash in his library.

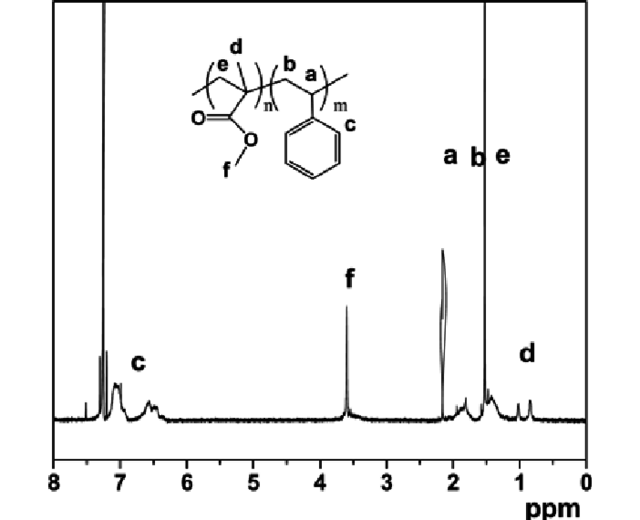

One weekend I went home and I was driving around with this friend. He told me about a podcast that had been listening to which included an old recording of Buckminster Fuller. Bucky was a famous (and controversial) scientist who is mostly remembered for designing the geodesic dome.

Buckminster Fuller in front of one of his famous geodesic domes. (Image source.)

Bucky never received a college degree and was known for being eternally frustrated with those who had. “Scientists” had become so specialized, they were useless outside of the specific field they were trained in. My friend described that Bucky was complaining about this problem in the scientific community during the recording. At one point Bucky became so upset, he shouted, “There are scientists that don’t know how plumbing works!” My friend did his best to imitate Bucky’s voice and shake his hands in the same frustrated manner to get the point across.

Stoned in the passenger’s seat, Bucky’s words echoed through my mind. A mirror rose up from the swirling depths of my psyche, and amidst the cacophony of my peers jeering at the uselessness of other subjects, the image in the mirror bore me down and said:

“...I don’t know how plumbing works.”

My classes were hard. We were doing math that would crush your soul; quantum mechanics involves multivariable integral calculus with operators and imaginary numbers. I had been learning how to operate and read incredibly advanced instrumentation for solving scientific problems in hours that used to take scientists months or even years to calculate. But… I didn’t even know how to mix the chemicals under my sink. I sure as shit didn’t know how plumbing works. Hell, I still don’t.

Does this look soul-crushing to you? (Image source.)

Bucky’s disrupting point was clear: if I didn’t understand basic mechanics of mundane technology, what business was it of mine to say I understood the complex? Did I really understand anything practical from my classes?

This thought followed me through the rest of my time in university. After I graduated (and quit my job that I theoretically went to the university to get), I made a decision. That decision was: I didn’t know anything. I needed to start from scratch. Throw everything out the window--any assumption I had about anything, especially that which I had learned in school. I began to read books and listen to podcasts, often up to eight hours a day. I dove into politics, economics, psychology, history, manufacturing, conspiracies, banking--anything that I had shirked while I was in college studying chemistry.

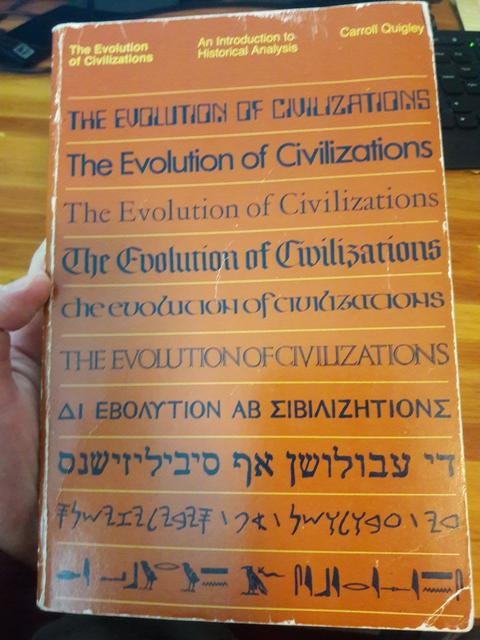

Eventually I stumbled across a book titled The Evolution of Civilizations by Carroll Quigley. (Quigley is famous for writing Tragedy and Hope.) Reading the book was like discovering a secret decoder that all my history teachers had kept from me. Quigley, who studied biochemistry before switching to history, opens the book discussing the importance of approaching history scientifically. Of course, this is difficult because you can’t put history in a test tube. Nevertheless, in order to make a history practical subject, one had to use it to extract patterns that could be identified in the present and the future. Quigley’s goal in the book, he wrote, was the make historians who were executives, not clerics.

My copy of The Evolution of Civilizations.

Of course, this scientific approach applies to all history, but as per the name of the book, Quigley focused on civilizations. But just what are civilizations? The definition is difficult, and Quigley doesn’t approach it lightly. They are too complex to describe with a few sentences, and no one had ever really given a solid definition of what a civilization is or isn’t. Quigley uses the book to propose his understanding of civilizations, and even suggests that his proposition is a prototype--something that will need further refinement. I have never found a source which addresses and attempt to build on his work, so I will need to start where he left off.

From Quigley’s book, I learned with fascination the life cycles of civilizations, and immediately one thing stood out: Western Civilization was different from all the rest. Something very specific made the West stand out. In order to understand what exactly it was that made the West stand out, we need to look at what a civilization is. As I mentioned, defining civilization is difficult, and Quigley took several chapters to lead up into his definition. I’m going to try to speed that up a bit, but I will use a similar approach to his. I’m going to describe the civilization life cycle so we can see breadth and width of the subject and hopefully work up to a definition.

In the next article I will detail what this life cycle is and the fundamental axiom that a civilization lives on, and begin to take a look at what makes Western Civilization stand out from all the rest.

-Dylan Lawrence Moore

@volsci

Follow, re-steem, and share. Thanks!

Follow me on Youtube!

Another excellent piece of this story, thank you!

I read a little on those cyclic stages a while back, so I really look forward to your take on their application. :)