Cerro Rico & The City of Potosí, Bolivia - The Influence ON EARTH and The Anthropocene

In the following essay, I want to analyse two dominant features, namely the mountain and the city (Cerro Rico & The City of Potosí, Bolivia) in the light of the human era of the Anthropocene. Thus, I will introduce firstly the geographic setting of the picture and the meaning as well as the impact of the mountain. After shortly introducing the concept of the Anthropocene and contextualising the mountain, I will shed a light on the city. Finally, I will sum up the relationship between the photo and the Anthropocene.

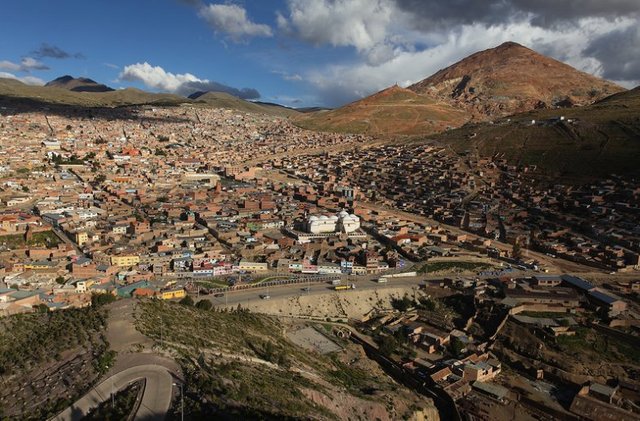

The picture shows Cerro Rico with the city of Potosí located in southwestern Bolivia. Cerro Rico is an Central Andean mountain with the worlds’ largest silver deposit (Cunningham et al., 1996; Rice et al., 2006). The rock layers of Cerro Rico were formed through volcanic eruptions in the Tertiary (Bartos, 2000; Strosnider et al., 2011). During the Spanish Empire silver was discovered here (Bartos, 2000). Thus, mining began intensively in 1545 and it became the largest industrial complex worldwide during the 16th century (Strosnider et al., 2011; UNESCO, 2016). The production of silver continued until the end of the 19th century and was followed by tin and zinc production (Bartos, 2000; Cunningham et al., 1996). Nowadays, about 20 000 miners are still working with the most primitive tools to extract zinc-silver lines while the mountain is already honeycombed with more than 5 000 mine shafts and adits covering 1 150 metres vertically (Bartos, 2000; Cunningham et al., 1996; Strosnider et al., 2011). Cerro Rico is so perforated with tunnel systems that even the peak might collapse (Shahriari, 2014).

The city of Potosí grew with the exploitation of the mine massively in population size and increased its environmental impact. Under the Spanish Empire, Potosí became the second most populated city in the western world and furthermore the richest in the whole world (Cunningham et al., 1996; Strosnider et al., 2011). This made the whole area economically sound for centuries, but also led to substantial human influence with massive deforestation and soil erosion (Strosnider et al., 2011). Moreover, unfiltered toxics were washed out into the city and surrounding areas (Strosnider et al., 2011). The population reached a peak in the 17th century with 160 000 inhabitants, whereas there are about 100 000 people nowadays (Pretes, 2002).

I contend that Cerro Rico is an artifact of the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is a concept that gained speed in 2000 when Paul Crutzen introduced his idea of the era (Carey, 2016). The core argument in the discussion is that humans are so dominant that they can be seen as a geological force (Chakrabarty, 2009). Ellis and Ramankutty (2008) showed that only 25 % of the earths’ ice-free surface are not altered by humans. However, researchers are still debating about details such as the start of the era (Foley et al., 2013; Steffen et al., 2011; Zalasiewicz et al., 2011; Zalasiewicz, 2015). Storm (2014, p. 1) illustrates nicely how mines and old industrial places ”are marks of sorrow and betrayal, of the abuse of power and latent hazards”. However, they carry as well many stories and are a part of our culture. This rich emotional and architectural history is what the author names post-industrial landscape scars. In other words, these man-made scars show a clear indicator for the power and the influence of humans on the earth. This applies also to Cerro Rico as a mine which bespeaks a prosperous past and the impact the mine had on its direct environment.

First, population density is an indicator for the influence of humans on surrounding ecosystems (Ellis and Ramankutty, 2008). People settled to produce basic needs, so it can be seen as the reason for dense populations and alterations where necessarily the consequence (Ellis and Ramankutty, 2008). Moreover, anthropogenic biomes appear in a mosaic pattern (Ellis and Ramankutty, 2008). This applies also to Cerro Rico as an island of urban settlement and big-scale mining activities within the Andes.

Second, the impact of the silver mine is not only concentrated on the geographic spot of Potosí and Cerro Rico. The extracted resources were further processed and distributed, which extends the scope further on the earth. It is often argued that only the mines of Cerro Rico enabled the flourishing Europe of the 16th and 17th century as the silver was mainly imported from Cerro Rico (Bartos, 2000; Moore, 2010). The connection of helping Europe to prosper and the Anthropocene is tough to identify, but Moore (2010) argues that the resources of Cerro Rico pathed the way for our current capitalist system. This system, which is based on exploitation has necessarily a huge impact on the earth. Moreover, the wealth generated through Cerro Rico was transferred to another part of the world. Therefore, the region could not become socially or ecologically resilient, because they could not accumulate or substitute their resources, but only exploited them (Moore, 2010). The environment was not able to protect itself through the massive influence of humans.

Third, Rockström et al. (2009) introduced the concept of planetary boundaries to keep the state of the Holocene, which is seen as “the safe operating space for humanity”. These nine planetary boundaries are influenced through mankind (Rockström et al., 2009) and mirror thus the Anthropocene. The intensive mining activities at Cerro Rico since several hundred years lead to a high contamination of the water, surface and sub-surface, as well as the sediments with several toxic metals (Moore, 2010; Strosnider et al., 2011). This applies to the Cerro Rico as well as the entire watershed. Even though there are measures and limits defined by the Bolivian government, these are not well controlled or fined yet (Strosnider et al., 2011). Hence, the planetary boundary chemical pollution is directly affected by Cerro Rico. Furthermore, the growth in population size as well as the connected increase of economic strength in Europe might have additionally influences on all other planetary boundaries.

Finally, Potosí is visited by more and more visitors around the year nowadays. It is not only the colonial city that attracts people, but also tours through the mine often led by indigenous Quechua who are mining workers (Pretes, 2002). Moreover, it is a World Heritage Site since 1987 (UNESCO, 2016). Therefore, the influence of Cerro Rico is still driving global environmental change. Tourism moves people in a globalized world on the costs of the environment through the use of fossil fuels and resources.

In conclusion, Cerro Rico and the city of Potosí is in my opinion an artifact of the Anthropocene. The rock layers which were formed in the Tertiary are nowadays so perforated that the stability of the mountain is at risk. This is a direct massive human influence, but extends furthermore to the whole world. Firstly, Potosí applies to the definition of an anthropogenic biome by Ellis and Ramankutty (2008). Secondly, it can be argued that the silver of Cerro Rico supported capitalism which is by nature a man-made system based on exploitation. Thirdly, the impacts of Cerro Rico apply to one, if not all, defined planetary boundaries of Rockström et al. (2009) which are driven by humans. Finally, even though the exploitation of Cerro Rico slowed down, increasing tourism is driving the influence of the mountain on the earth further. Due to these massive and far-reaching impacts of Cerro Rico on the global environmental patterns it can be argued that Cerro Rico is a silver bullet for the Anthropocene.

References:

Bartos, P. J. (2000) ‘The Pallacos of Cerro Rico de Potosi, Bolivia: A New Deposit Type’, Economic Geology, vol. 95, no. 3, pp. 645–654.

Carey, J. (2016) ‘Core Concept: Are we in the “Anthropocene”?’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 113, no. 15, pp. 3908–3909.

Chakrabarty, D. (2009) ‘The Climate of History: Four Theses’, Critical Inquiry, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 197–222.

Cunningham, C. G., Zartman, R. E., McKee, E. H., Rye, R. O., Naeser, C. W., Sanjinés V, O., Ericksen, G. E. and Tavera V, F. (1996) ‘The age and thermal history of Cerro Rico de Potosi, Bolivia’, Mineralium Deposita, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 374–385.

Ellis, E. C. and Ramankutty, N. (2008) ‘Putting people in the map: Anthropogenic biomes of the world’, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, vol. 6, no. 8, pp. 439–447.

Foley, S. F., Gronenborn, D., Andreae, M. O., Kadereit, J. W., Esper, J., Scholz, D., Pöschl, U., Jacob, D. E., Schöne, B. R., Schreg, R., Vött, A., Jordan, D., Lelieveld, J., Weller, C. G., Alt, K. W., Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S., Bruhn, K.-C., Tost, H., Sirocko, F. and Crutzen, P. J. (2013) ‘The Palaeoanthropocene – The beginnings of anthropogenic environmental change’, Anthropocene, vol. 3, pp. 83–88.

Moore, J. (2010) ‘”This lofty mountain of silver could conquer the whole world”: Potosí and the political ecology of underdevelopment, 1545-1800’, The Journal of Philosophical Economics, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 58–103.

Pretes, M. (2002) ‘Touring mines and mining tourists’, Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 439–456.

Rice, C. M., Steele, G. B., Barfod, D. N., Boyce, A. J. and Pringle, M. S. (2006) ‘Duration of Magmatic, Hydrothermal, and Supergene Activity at Cerro Rico de Potosi, Bolivia’, Economic Geology, vol. 100, no. 8, pp. 1647–1656.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S., III, Lambin, E., Lenton, T. M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H. J., Nykvist, B., Wit, C. A. de, Hughes, T., van der Leeuw, S., Rodhe, H., Sörlin, S., Snyder, P. K., Costanza, R., Svedin, U., Falkenmark, M., Karlberg, L., Corell, R. W., Fabry, V. J., Hansen, J., Walker, B., Liverman, D., Richardson, K., Crutzen, P. and Foley, J. (2009) ‘Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity’, Ecology and Society, vol. 14, no. 2.

Shahriari, S. (2014-01-10) ‘Bolivia’s Cerro Rico, the ‘mountain that eats men’, could sink whole city’, The Guardian, 10 January.

Steffen, W., Grinevald, J., Crutzen, P. and McNeill, J. (2011) ‘The Anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives’, Philosophical transactions. Series A, Mathematical, physical, and engineering sciences, vol. 369, no. 1938, pp. 842–867.

Storm, A. (2014) Post-industrial landscape scars, New York, NY, Palgrave Macmillan.

Strosnider, W. H. J., Llanos López, F. S. and Nairn, R. W. (2011) ‘Acid mine drainage at Cerro Rico de Potosí I: Unabated high-strength discharges reflect a five century legacy of mining’, Environmental Earth Sciences, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 899–910.

UNESCO (2016) World Heritage Site: City of Potosí [Online], Paris. Available at http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/420/ (Accessed 4 December 2016).

Zalasiewicz, J. (2015) ‘Epochs: Disputed start dates for Anthropocene’, Nature, vol. 520, no. 7548, p. 436.

Zalasiewicz, J., Williams, M., Haywood, A. and Ellis, M. (2011) ‘The Anthropocene: a new epoch of geological time?’, Philosophical transactions. Series A, Mathematical, physical, and engineering sciences, vol. 369, no. 1938, pp. 835–841.

Congratulations @fugetaboutit! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP