4 Economic Shifts That Could Push Interest Rates Higher

Most people think interest rates are the result of a central bank decision. The Fed sets the rate, and voilà – zero percent interest. While this seems to be true on the surface, the Fed’s and every other central bank’s target rate is actually dependent upon a manipulation of sorts in the bond market.

In my last post, I shared “7 Ways Higher Interest Rates Will Reshape The World Economy.” In this follow up, I’ll explain how exactly rates could rise, even at a time it seems central bankers are committed to keeping rates low forever.

Central Bankers vs. The Free Market

When Janet Yellen hiked the Fed funds rate for the first time in nearly a decade, she declared her new policy was “likely to proceed gradually.” It wasn’t hard to realise at the time that she was bluffing.

That rate rise was only symbolic. Financial markets have become addicted to cheap credit, and central bankers know that long-term, higher interest rates would dramatically reshape the world economy, as I explained in my last post.

I fully expect the Fed to change course in the not-too-distant future, and return interest rates to zero. They’ll blame the policy shift on some new economic data or unforeseen world event.

But that’s not a guarantee of low borrowing costs. There are economic forces outside of the control of the Fed, the ECB, the BOJ, and the RBA, that can push interest rates higher. Those forces are at work in the free market.

Given enough time, the free market will always win.

How Central Banks Manipulate Interest Rates

If a central bank wants to change its overnight lending rate, it must manipulate the supply and demand of bonds, which represent debt in the economy. To lower the cash rate, it buys more bonds to drive up bond prices, which then lowers the yield.

By effectively driving down the yield on bonds, the central bank ensures that banks borrow from and lend to one another, at or near the new lower target interest rate. The idea is that the banks will then pass on that savings to their customers in the broader economy, and interest rates at large, will fall.

In order to buy bonds and drive down interest rates, central banks must create new money out of thin air, or digitally on a network server, to be precise. This increases the money supply and drives down the perceived value of our dollars.

As long as nothing crazy happens in the broader economy and people maintain faith in the currency, the central bank can manipulate the credit market to its heart’s content, at least to a degree. Central banks must work within the confines of a free market, so there are forces outside of its control that could cause interest rates to rise.

Fed President Janet Yellen has admitted, “The Federal Reserve’s control over longer-term interest rates is more indirect and more limited than its influence over the level of the federal funds rate.”

In Yellen’s words, central banks can influence rates for the short term, but they can’t necessarily control them for the long term. The market forces at work are just too great.

4 Economic Shifts That Could Push Interest Rates Higher

In light of this harsh reality, here are four economic shifts that could someday test the limits of every central bankers power and push interest rates higher:

1. If Inflation Spikes Out of Control

The RBA’s stated goal, where I live in Australia, and that of virtually every Western central bank, is a target inflation range of two to three percent per year. Our regulators believe if things get a little bit more expensive each year, it’s a sign the economy is healthy and growing.

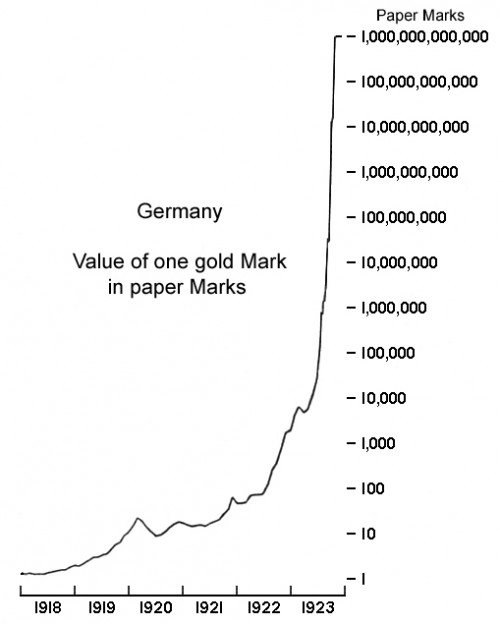

Unfortunately, you can have too much of a “good” thing. Many times in history, the creation of new money has led to undesirable levels of inflation. Here are some of the more painful past and present examples of inflation:

- Soviet Union: 213% per annum in 1922.

- Germany: 29,500% per month in 1923. Check out the 100 Billion Deutsche Banknote.

- Greece: 13,800% per month in 1944.

- Hungary: 207% per day in 1946.

- China: 2178% per month in 1949.

- Bolivia: 60,000% per annum in 1985.

- Nicaragua: 30,000% per annum in 1987.

- Vietnam: 774% per annum in 1988.

- Argentina: 12,000% per annum in 1989.

- Yugoslavia: 313,000,000% per month in 1993. The 500 Billion Dinar is pictured above.

- Romania: 31% per annum in 1997.

- Zimbabwe: 516 quintillion percent per annum in 2008. This resulted in a 100 Trillion Zim Dollar note.

- Venezuela: 500% per annum in 2016.

Western economies face a similar risk today. If central banks continue to increase the money supply indefinitely, as it appears will be the case, we will eventually experience higher than normal inflation. It’s an unavoidable reality of the economics of money.

I hope our regulators will eventually raise rates to prevent this, as a moderate amount of pain today would be better than complete and utter chaos in the future, but I’m not holding my breath.

If our elected officials lack the political will to rein in debt, inflation will spike. It’s unavoidable. As a result, lenders would force rates to rise, regardless of any central bank’s monetary policy. Investors will demand compensation for the loss in buying power of their money. No sane lender will agree to be paid back with worthless future dollars.

2. If a Fiscally Irresponsible Government Borrows Into Oblivion

Governments borrow by issuing bonds. A bond is a promise to pay back a defined sum of money within a specified period of time at a particular interest rate, or yield. Initially, investors buy those bonds on the primary market upon issuance, but then they are traded between investors on the secondary market.

The more governments around the world borrow, the greater the supply of bonds there are in the primary and secondary markets. This greater supply of bonds means more secondary sellers are competing for fewer buyers. When buyers have more choices, bonds get cheaper, which means yields go higher.

Because bond prices and yields have an inverse relationship, when prices of bonds go down, the yields on those bonds go up. Yield is essentially another word for interest rates. As yields rise in the bond market, there will be a knock-on effect of higher interest rates in the broader economy.

Unless your country can slow down its pace of borrowing – and that doesn’t appear to be happening anytime soon – market forces will eventually push interest rates higher. An oversupply of bonds will guarantee that.

3. If Investors Flee Bonds for Safer or Higher Yielding Assets

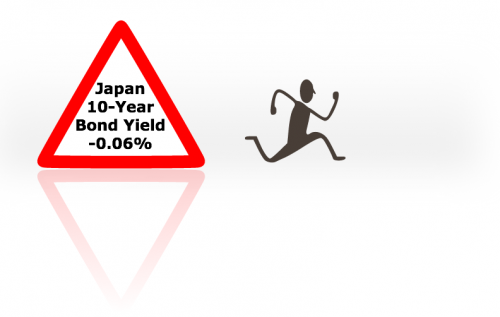

Investor demand for bonds also has a significant influence on interest rates. Smart investors are always looking for the highest return for the least risk, in the shortest amount of time.

Because interest rates have been so low for so long, bond prices have risen dramatically. Investors have been happy to receive an exceptionally low yield on most government bonds because of the perceived low level of risk, and because there are few other “safe” options.

But bond values can only go so high. Eventually, the bond bubble will burst, and investors will flee to other assets, whether seeking higher returns or greater safety. When that happens, prices will fall and yields will rise. The impact will be higher borrowing costs in the overall economy.

4. If Your Nation’s Credit Rating Takes a Hit

Similar to a household, a government can only sustain so much debt, given a particular level of income or tax revenue. Nations with low incomes or high levels of debt represent a greater credit risk to its borrowers, the bond purchasers.

Agencies like Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s issue credit ratings to various countries, which measure the borrower’s ability to repay, as well as the risk of default. Of course, these agencies are run mostly by incompetent idiots who are in bed with central planners, but that’s a topic for another article.

In theory, a country with a triple-A rating is an extremely low risk, and as a result would pay a low interest rate. On the other hand, investors demand higher yields from bond issuers with poor credit ratings.

For example, Australia has a coveted AAA credit rating with Standard & Poor’s and currently pays about 2 percent on a 10-year bond.

South Africa, on the other hand, has a BBB credit rating, so it pays almost 9 percent.

Therefore, the credit rating of a nation significantly impacts its borrowing costs and potential for debt-fueled economic growth.

While Australia has a high rating currently, it also continues to run a budget deficit. We have yet to see if any politician has the political will to change this. Even if they did, they wouldn’t likely stay in power for long. There are too many people at the voting booth looking for a handout.

If our politicians keep borrowing to try to stimulate our economy, as the RBA governor has recently suggested, buyers of Australian debt will eventually begin to demand higher interest rates. These investors will want compensation for the greater risk created by excessive government spending for our entitled population. The impact will be higher interest rates.

Why You Should Care

Over time, governments that keep borrowing will reach a tipping point of indebtedness where only two options remain:

Option one is to default, which would be both embarrassing and painful, so it’s unlikely.

Option two is to inflate the currency, and then repay the debt with worthless money. That is just as painful, but less embarrassing, because politicians can blame the inflation on something other than their own fiscal irresponsibility.

Higher interest rates will have a profound impact on our economies and on the value of assets like shares and real estate. We all need to recognise the market forces that influence borrowing costs which, in turn, affect borrower’s access to credit, especially for housing.

It’s anyone’s guess how long central banks will be able to suppress interest rates and keep asset prices inflated. We may continue on the current path for many more years, or maybe not. Either way, we should be able to see the warning signs before the economic shift takes place. If so, we will be in a better position to make wise decisions with our money.

Any thoughts you’d like to share? Please leave a comment.

@jasonstaggers

image credits: rocketing rates, boxing kangaroo, Yellen caricature, 500 billion dinars, German inflation chart, US debt clock, low-yield bond danger, S&P ratings map, AU bond yield chart, SA bond yield chart, thinking dude

I originally shared some of these ideas in an article I wrote for PropertyInvesting.com.

@jasonstaggers - thank you, very well written.

Do you think interest rate is a political or economic decision? I mean not just those "symbolic" moves as you said, but longer term ones?

Yeah, that's an interesting question. I think there's a little of both, although not necessarily from an altruistic perspective on the economic side. You have to look at who benefits the most from current policy, and it's clearly the banking industry and those in the pockets of bankers (mainly politicians) and whoever else pulls the strings behind the scenes. The two biggest drivers for selfish human beings seem to be power and money, which would make monetary policy both political and economic in a sense.

Another issue that comes to mind is what I brought up about the entitlement of a culture leading politicians to be fiscally irresponsible for the sake of more votes. That keeps the cycle of monetary easing going as well.

What are your thoughts?

Its not a matter of it, but when. I've made a few "bets" over the past couple years on rising inflation. Still to early, crazy it's gone this long. Shorting bonds 3 years ago was a good idea and it's still a losing trade.

On the flipside, this is why I started grabbing real estate. 30 year money at 3.5%. Yes, please. So long as one does not overleverage and only buys cash flowing property then it make sense.

Surprised the late 80s-early 90's Brazil didn't make the list, that was crazy inflation. I believe they are a rare case of actually inflating their way out of debt back then. Of course, they are a hot mess now though.

@scaredycatguide - agree.

On inflation - you should be definitely get paid on your bets, especially taking into account the actual inflation, not what US Statistics bureau publishes... ;)

If we do see inflation, you'll pay those fixed rate mortgages back quite easily. I've always been amazed by how quick Aussies are to speculate on very expensive, negative cash flow real estate using a variable rate mortgage. It's worked out OK so far but I don't think people realise just how much they owe to the RBA for their success.

Oh goodness. That is worry some. That sounds like the scenario of the U.S. before the bubble burst. Plus - variable rate mortgages were one of the main issues that led to the American foreclosure saga. I may need to short Aussie housing market!

I like the list of countries inflation rates when it was totally out of control.

I wonder who the next one will be!

Jason, You said:

I believe, in the US at least, we have already gotten to the point of no return. There is no way the US can pay back all the money, and to raise rates would compound (pun intended) their problem. Either option will ruin a country.

Agreed. And eventually option 1 will lead to higher interest rates too regardless of whether the Fed raises the overnight lending rate.