War is a Rent Seeking Racket: Why War Doesn't Boost the Economy

Originally posted in Syncretic Politics January 2020

Sources: DOD cost of war Oversight of U.S. spending in Afghanistan Human costs of the post 9/11 wars Department of Defense Contractor and Troop Levels in Iraq and Afghanistan: 2007-2018 Boeing Overcharged Army up to 177,000% on Helicopter Spare Parts 20 Companies Profiting the Most From War Interest on The National Debt and How it Affects You Interest on National Debt Could Top $1 Trillion The Fed’s Lower Rates are Increasing Inequality

The notion that war time spending boosts the economy is obviously false in light of the fact that the U.S. was involved in 2 wars, more extensively than they are now, and oil prices were at their peak right before the great recession, but this example does not do it complete justice. The broken window fallacy, as first described by classical French economist Frederic Bastiat, is the notion that destruction can stimulate the economy. In the parable, broken windows are presumed to be good for the economy because they give the glazer business and provide him with disposable income to purchase other goods and services. However, the bystanders don’t take into consideration that the broken window has decreased the disposable income of the man who purchased the glazer’s service and that the cost of a new window does not represent the provision of a new good, but merely a maintenance cost (presumably because the demand for windows is inelastic); thus, no net wealth is added by breaking windows. Of course, macroeconomics is much more complex than the example given in this parable, but the basic principle remains the same, especially in clear cut examples like wars and natural disasters. Both involve the destruction of wealth. Any rebuilding done in their aftermath is merely maintenance costs. This may not be obvious to Americans since war hasn’t been waged on American soil since the 19th century, but it holds just as true for wars waged abroad. After a region is bombed it has to be rebuilt. Congress has spent $126 billion rebuilding Afghanistan since 2002. This exceeds the cost of the Marshall Plan, foreign aid given to rebuild Europe after WWII, even when adjusted for inflation. The Marshall Plan cost $12 billion at the time or $100 billion in today's dollars but was committed to rebuild an entire continent after a world war instead of some podunk Eurasian country after a counter-insurgency. Over the course of the past 18 years, the state department has not created $126 billion in additional wealth, but $126 billion in maintenance costs redistributing resources from this country to Afghanistan. This isn’t the entire maintenance cost though. It does not include the estimated $750 billion spent on military operations since the invasion, or the $87 billion spent training Afghan security forces who are still unable to fend off the Taliban, or the $10 billion spent on a counter-narcotics program that has somehow increased the supply of opium from that country, or the $24 billion spent on economic development that has still left 25% of Afghanis unemployed, or the $500 billion in interest payments added to the national debt or the $350 billion spent on medical and psychiatric care for veterans of the war. It also does not include the cost of 2,400 American lives and 38,000 Afghani lives which do not have a price tag.

’The normal profits of a business concern in the United States are six, eight, ten, and sometimes twelve percent. But war-time profits -- ah! that is another matter -- twenty, sixty, one hundred, three hundred, and even eighteen hundred per cent -- the sky is the limit. All that traffic will bear. Uncle Sam has the money. Let's get it.’- Major General Smedley Butler, War is a Racket

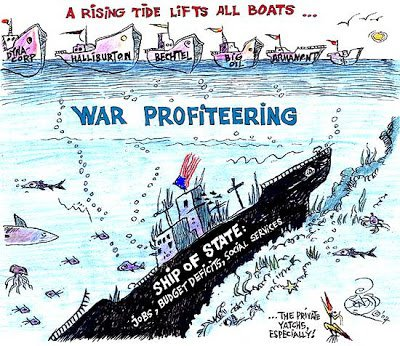

The military industry is a rent-seeking industry; while it does deliver profits to shareholders it does not grow the pie. History has repeatedly shown that war simply redistributes income and resources from the private sector to the public sector or to certain private industries dedicated to the construction and maintenance of military equipment as well as the oil industry. For instance, during WWII consumer goods were rationed, Americans were encouraged to buy war bonds as a counter inflationary measure, and the national debt increased six fold rising to a record 113% of GDP. While the war effort may have reduced unemployment it did not create additional wealth (i.e. new or improved goods and services) but merely redistributed them from the private to the public sector. The same principle holds true for today’s war on terror. The profits of the Defense Industry are directly the result of congressional appropriations, which thus far has squandered $6.4 trillion on wars in Iraq and Afghanistan including $1 trillion in care for veterans of these wars and over 200 billion in contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan between 2007 and 2018. About 17% of this cost, or $925 billion, has been borne out in interest payments on the public debt accumulated through DOD and State Department spending over the past two decades. Annual net interest on the national debt ,which currently stands at $479 billion (over 10% of the 2020 budget), is the fastest growing category of spending. It is projected to increase 186% over the next decade, while GDP (real wealth) is only projected to grow 53% over the same period, and exceed $1 trillion annually by the year 2030 eclipsing and crowding out all categories of discretionary spending, including defense spending by 2025. In other words, interest on the national debt will grow faster than real wealth is created, causing public debt to surpass resource constraints (which is when the MMT crowd says we have an inflation problem), and consume an ever larger portion of the budget. The Federal Reserve’s response to higher levels of stimulus spending since the great recession of 2008/2009 has been to keep interest rates, for banks, artificially low through QE which has had the perhaps intended effect of exacerbating wealth inequality. Since stock and bond prices are inverse to the federal fund rate, and since these assets are almost exclusively owned by the affluent, rich investors have gotten richer. Poor workers, on the other hand, have seen very few benefits from lower rates since lower fed rates have had very little effect on credit card interest rates and mean lower savings rates relative to inflation in consumer goods. Real estate prices too have soared as a result of lower borrowing costs which has been profitable for homeowners and landlords at the expense of renters who are mainly people on the lower end of the income distribution who eat a larger sunken cost instead of accruing a higher capital gain.

Your post was upvoted and resteemed on @crypto.defrag